Lord Berners

ENDNOTES, September 2019

Stuart Millson on the film music of Lord Berners

In 1944, the directors at Ealing Studios (Basil Dearden, Alberto Cavalcanti and Michael Balcon) were working on a new production, The Halfway House– a story set mainly in a rural location, this time at a remote Carmarthenshire inn, far from the madding crowd and far from the war – or so it seems at the beginning of the story. The story is one of wartime – and of a connection to an ethereal dimension. Yet the spirits in The Halfway House appear as everyday, “real” characters (played by Mervyn and Glynis Johns) – guardians of a gateway to a dimension, a year back in time, in which someone can find again the chance to re-live and re-adjust their life.

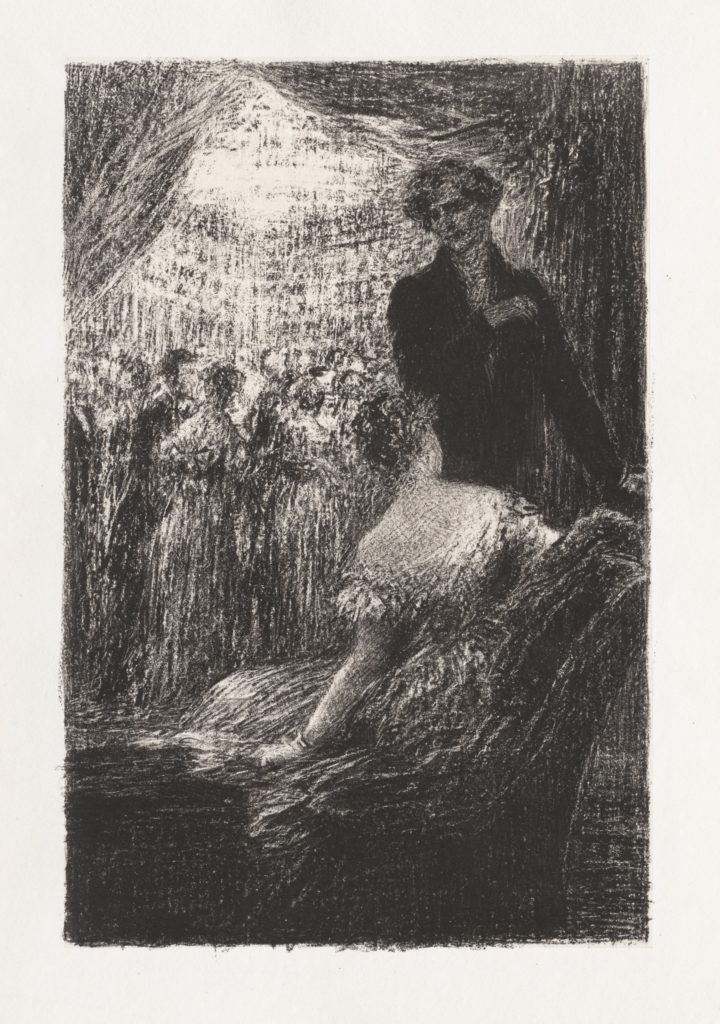

Suggested by a play by Denis Ogden, The Peaceful Inn, Ealing’s supernatural and rural journey to Wales, begins at a concert in Cardiff, at the famous New Theatre. Orchestral conductor David Davies (played by Esmond Knight) leads his players in a sparkling, thrilling passage of music – the actual score, especially written for the film by the English composer, Lord Berners. After the applause dies down, Davies addresses his audience, telling them how proud he is to be back on home soil after so long. Seemingly exhausted by his efforts, he drags himself to his dressing room, and we soon learn (his doctor is standing by) that he has been given just a few weeks to live.

The conductor, still a young man, contemplates the awful news, but is determined to take his orchestra on an important British Council tour. Willing himself to squeeze every drop out of life, he refuses to ‘see reason’, but does agree to take a short break from his busy schedule, having been reminded by his elderly backstage attendant of ‘the old ‘alfway house’ – the perfect place, not far from Llandeilo, in which to recharge the batteries. Davies is distracted, and absent-mindedly plays a few notes of a Welsh folk-song on the piano in his dressing room, a small but significant moment in the film, deeply suggestive of old memories and half-forgotten places summoning the characters to their mysterious rendezvous. It is time to go home: Davies puts on his overcoat and hat, and like a shadow, leaves through the artists’ door – a stage direction in itself, and a symbol of what awaits him.

The landlord of the inn, Rhys (Mervyn Johns) materialises, like a figure from the shadows and the air. He is pleased to see his guests arriving, but seems to be absorbed by other thoughts, gazing through time and space. Then a warm, tender, pastoral theme from Berners introduces the arrival of Rhys’s daughter, Gwyneth (played by Glynis Johns). For this moment, Berners produces what must be one of his warmest, most romantic passages: a short tone-painting of hardly any length, yet which manages at a stroke to conjure a feeling of summer air and light, and a touching sense of the love re-uniting two people.

The film also includes a séance, for which Berners composed a gentle, subdued waltz – music from the shadows and footlights. At other times in the screenplay, in which some of the visitors quarrel with one another (two unhappy marriages, and an ardent courting couple, who discover political differences) the composer produces bitter-sweet themes: music of great sadness, at odds with the beauty of the surroundings. The camera also captures magnificent views of wild, hilly country, with suitably uplifting (and, perhaps, slightly out-of-character) music from Berners, but which then subsides into a Bax-like brooding and sense of mystery and Celtic landscape.

The Halfway House concludes with a bombing raid which leads to the destruction of the inn, but not before the principal players have been granted (by Rhys) the chance to re-live the last year of their lives. Actor Esmond Knight is brought to the fore again, to read the words of the 23rd Psalm: ‘The Lord is my shepherd… he maketh me to lie down in green pastures… Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil…’ It is here that Berners reaches a rare spiritual intensity and, for once, a non-tongue-in-cheek Englishness, with celestial voices guiding the characters through the wartime flames, with a fleeting glimpse of heaven, and back into what Rhys describes as ‘a good world’.

Rarely in British cinema – even in the Walton-Olivier Henry V – can we find such an uplifting conclusion.

Stuart Millson is the Classical Music Editor of The Quarterly Review

Lord Berners, film music (including The Halfway House), Chandos, CHAN 10459

Like this:

Like Loading...

Blessed are the Peacemakers

Marquess of Lansdowne

Blessed are the Peacemakers

Lansdowne; The Last Great Whig, Simon Kerry, Unicorn, 398pp, 2017, ISBN 978-1-910787-95-3, reviewed by Angela Ellis-Jones

This biography of Lord Lansdowne, one of late Victorian and Edwardian Britain’s most distinguished people, is written by the subject’s great-great grandson, who modestly omits to mention that he is the heir to the current Marquess. Lansdowne was born into the Whig aristocracy. The founder of the family fortune was Lansdowne’s four-times great grandfather, Sir William Petty (1623-87), the son of a clothier who began his working life as a cabin boy but subsequently enjoyed a brilliant polymathic career. After he had served as Professor of Anatomy at Oxford (1651-2) and of Music at Gresham College, London, a stint as physician to Cromwell’s army in Ireland led to his appointment as director of the land survey of Ireland for the purpose of dividing the spoils amongst Cromwell’s men. He finished the first complete map of Ireland in 1656, and amassed 270,000 acres of land in south Kerry alone. When he made his will in 1685, he calculated his annual income to be £15,000, an enormous sum at a time when the annual average was just short of £7!

Just as Petty was a member of a brilliant intellectual circle – he was a founder of the Royal Society – so also was his great-grandson, the second Lord Shelburne (1737-1805), who became the first Marquess of Lansdowne following his time as prime minister (1782-3), during which he negotiated the settlement of the American War of Independence. Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen while he held the position of librarian at Bowood. Bentham was a visitor to the house which Shelburne commissioned Robert Adam to decorate, and filled with beautiful paintings, furniture and sculpture. Shelburne’s son, Lansdowne’s grandfather, had been chancellor of the Exchequer at the age of 25, in 1806.

With such ancestors, Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, fifth Marquess of Lansdowne (1845-1927) was evidently well-endowed intellectually. The son of a half-French mother of distinguished lineage, he grew up bilingual. After he narrowly missed a First in Greats at Oxford, his tutor, the renowned Benjamin Jowett, commiserated: ‘You have certainly far greater ability than many First Classmen’ (Lord Newton, 1929, Lord Lansdowne, p 9). Jowett later saw him as prime ministerial material. Continue reading →

Share this:

Like this: