Marquess of Lansdowne

Blessed are the Peacemakers

Lansdowne; The Last Great Whig, Simon Kerry, Unicorn, 398pp, 2017, ISBN 978-1-910787-95-3, reviewed by Angela Ellis-Jones

This biography of Lord Lansdowne, one of late Victorian and Edwardian Britain’s most distinguished people, is written by the subject’s great-great grandson, who modestly omits to mention that he is the heir to the current Marquess. Lansdowne was born into the Whig aristocracy. The founder of the family fortune was Lansdowne’s four-times great grandfather, Sir William Petty (1623-87), the son of a clothier who began his working life as a cabin boy but subsequently enjoyed a brilliant polymathic career. After he had served as Professor of Anatomy at Oxford (1651-2) and of Music at Gresham College, London, a stint as physician to Cromwell’s army in Ireland led to his appointment as director of the land survey of Ireland for the purpose of dividing the spoils amongst Cromwell’s men. He finished the first complete map of Ireland in 1656, and amassed 270,000 acres of land in south Kerry alone. When he made his will in 1685, he calculated his annual income to be £15,000, an enormous sum at a time when the annual average was just short of £7!

Just as Petty was a member of a brilliant intellectual circle – he was a founder of the Royal Society – so also was his great-grandson, the second Lord Shelburne (1737-1805), who became the first Marquess of Lansdowne following his time as prime minister (1782-3), during which he negotiated the settlement of the American War of Independence. Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen while he held the position of librarian at Bowood. Bentham was a visitor to the house which Shelburne commissioned Robert Adam to decorate, and filled with beautiful paintings, furniture and sculpture. Shelburne’s son, Lansdowne’s grandfather, had been chancellor of the Exchequer at the age of 25, in 1806.

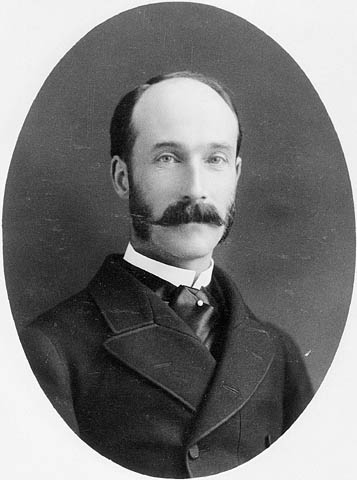

With such ancestors, Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, fifth Marquess of Lansdowne (1845-1927) was evidently well-endowed intellectually. The son of a half-French mother of distinguished lineage, he grew up bilingual. After he narrowly missed a First in Greats at Oxford, his tutor, the renowned Benjamin Jowett, commiserated: ‘You have certainly far greater ability than many First Classmen’ (Lord Newton, 1929, Lord Lansdowne, p 9). Jowett later saw him as prime ministerial material.

Having inherited his father’s titles and estates while at Oxford, great wealth did not corrupt him. Lansdowne, now head of one of the great Whig families, was offered a junior Lordship of the Treasury in Gladstone’s first government – at the age of nearly 24! Four years later he accepted the post of Under-Secretary of State for War. In 1880, he was appointed Under-Secretary of State for India, an office from which he soon resigned over Gladstone’s Irish Land Bill. His resignation, says Kerry, was ‘the first distinguished step of a career in which the defence of the landowning class against a threat from the left was to be a principal theme’ (p 28) He did not lack occupation in these years; one of his posts was that of chairman of the Joint Committee of the two Houses on the Channel Tunnel proposals.

As a prominent Anglo-Irish landlord and critic of government policy, Lansdowne was a threat to Gladstone, who may have wished to remove him from domestic politics. In 1883, he was appointed Governor General of Canada, an office he discharged with ‘unfailing dignity and polished grace’. This required great courage; Lansdowne’s status as an Irish landlord meant that the threat of assassination from Fenians was omnipresent. In 1888, on the suggestion of Queen Victoria, he was appointed Viceroy of India, the premier Imperial appointment. On his retirement from the viceroyalty in 1893, Victoria wished to offer him a dukedom, as she had offered one to his grandfather, but Gladstone vetoed it. Lansdowne was relieved, as he did not have the financial means to support a dukedom. Throughout his life, he was, like many of his class, asset-rich, cash-poor, and sold a succession of properties and paintings to make ends meet.

In 1869, Lansdowne married Lady Maud Hamilton, who bore him two sons and two daughters. Lady Maud was the daughter of the first Duke of Abercorn, Ireland’s premier peer, who was Lord Lieutenant (Viceroy) of Ireland on two occasions. The marriages of all of her six sisters to other peers meant that the Lansdownes were members of one of the largest aristocratic kinship networks; Lansdowne himself was extensively related to the Whig peerage. Lansdowne’s differences with Gladstone, and the fact that five of his six Hamilton brothers-in-law served as Conservative MPs, meant that he was increasingly drawn rightwards and, like most of the Whigs, left the Liberals to join the Liberal Unionists in 1886.

After his Viceroyalty ended, honours were showered upon him: the degree of DCL at Oxford, the Lord-Lieutenancy of his county (Wiltshire), the offer of the Embassy at St Petersburg. He was also made a Knight of the Garter. When Lord Salisbury became Prime Minister for the second time in 1895, he appointed Lansdowne War Secretary. In November 1900, when Salisbury decided that he could no longer continue as his own Foreign Secretary, Lansdowne succeeded him. Lansdowne gained plaudits for negotiating the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902, and the Entente Cordiale in 1904. When the Conservatives left office in 1905, Lansdowne, at any rate, could hold his head high.

On the deaths of Lord Salisbury in 1902 and Lord Goschen in 1907, Lansdowne was offered the position of Chancellor of Oxford University. On both occasions he declined this prestigious role. In 1903, he became the official leader of the Unionist Party in the House of Lords, a position he held until his retirement in December 1916, forced by the fact that Lloyd George did not invite him to join his wartime coalition.

As his earlier biographer, Lord Newton, wrote of him, he ‘represented the very finest type of what the old patrician system of this country could produce, for no one ever understood more fully the obligations of his class or lived more closely to the ideals expressed in the family motto “Virtute non verbis”’ (Newton, p 496).

In one of the most interesting chapters of the book, the author addresses the Unionist response to the Liberal landslide of 1906. From the late nineteenth century, differences between the House of Lords and Liberal governments had become increasingly salient. Lord Salisbury adopted what he called the referendal theory – the Lords’ duty was not to act as a pale shadow of the Commons but to represent the permanent feelings of the nation. Since the views of the Commons and the will of the people were not always consonant, the Lords had a duty to reject contentious bills. The government could then decide whether to call a general election on the issue. The best-known example of this was the Lords’ rejection of Gladstone’s second Home Rule Bill in 1893, for which there was clearly not a preponderance of support in the country. The resounding Unionist victory in the general election of 1895 was ascribed largely to the Unionist opposition to Home Rule, and totally vindicated the Lords’ stance.

Britain has never had a written constitution, so Conservative/Unionist views on many of its aspects coexisted alongside Liberal ones. The referendal theory of the House of Lords was matched by the Liberal view that the representative nature of the House of Commons meant that its views should prevail. To which the Conservatives replied that the voters choose one party offering many policies, and that not all of a party’s voters should be assumed to endorse all of its policies. Moreover, public opinion can change in the years following a general election. It is strange that Kerry concedes far more to his ancestor’s opponents than he needs to, stating ‘Lansdowne himself did not strictly adopt Salisbury’s referendal theory, but he and Balfour – in defiance of accepted parliamentary government – continued to invoke this theory to justify the Lords’ legislative veto’. The whole point is that their invocation of the referendal theory was not ‘in defiance of accepted parliamentary government’ – this was strongly contested at the time, and was not settled until the passage of the Parliament Act 1911. Indeed, if the Unionists had won the January 1910 general election, the referendal theory would have prevailed, and history would not have judged the Lords to have behaved ‘unconstitutionally’.

Starting from this false premise, Kerry criticises the stance that Lansdowne and Balfour took in relation to the Lloyd George budget. In Lloyd George and the Lords – the British Constitution in Crisis, I examined the episode from the viewpoint of the Lords which, because they lost, has never had a fair hearing. I disagree with Kerry’s characterisation of this episode as ‘a disastrous error.’ Rather, we need to ask why two such highly intelligent men as Balfour and Lansdowne took the course of action that they did. They were experienced politicians: both had moved in the highest political circles since their twenties. Balfour was considered to possess the subtlest political intelligence of his generation. By 1909, Lansdowne, according to Lord Newton, was “regarded as one of the best Parliamentarians of the day’ (Newton, p 457). Was this a case of clever men doing stupid things, as happens not infrequently? Or was there method in their ‘madness’? Anyone who reads their contributions to the various debates, especially Lansdowne’s of November 30, can see that they had good reasons for rejection.

Because the Budget clearly breached the conventions against ‘tacking’ (the inclusion of non-financial subject-matter), it was vindictively targeted at one section of the community, and its author gave plenty of hints that worse was to come. Balfour and Lansdowne saw the Budget as the critical battle for property in their time and that failure to resist would be a ‘cowardly betrayal’ of the interests they represented. A significant number of Liberal MPs and a majority of the Cabinet found the land taxes unacceptable; several of the latter expected that such a Budget would be rejected. For the Unionists, the Budget was the epitome of Socialism. The preservation of the traditional political, social and economic order depended on the survival of a strong Upper Chamber; it was about time that the House exercised its full powers, even in the controversial area of finance. As Balfour put it: ‘I do not see how the House of Lords could ever intervene usefully in the future if it accepts a deliberate slap in the face now’.

During the Great War, Lord and Lady Lansdowne contributed to the war effort. Lansdowne House became the HQ of the Officers’ Families Fund, set up by Lady Lansdowne in 1899, which had raised over £310,000 in 1916. Like many aristocratic ladies, Lady L ran a hospital for repatriated injured soldiers – starting with 20 beds at Bowood in September 1914, and, by the end of 1917, sixty. She was also involved with the British Red Cross Society.

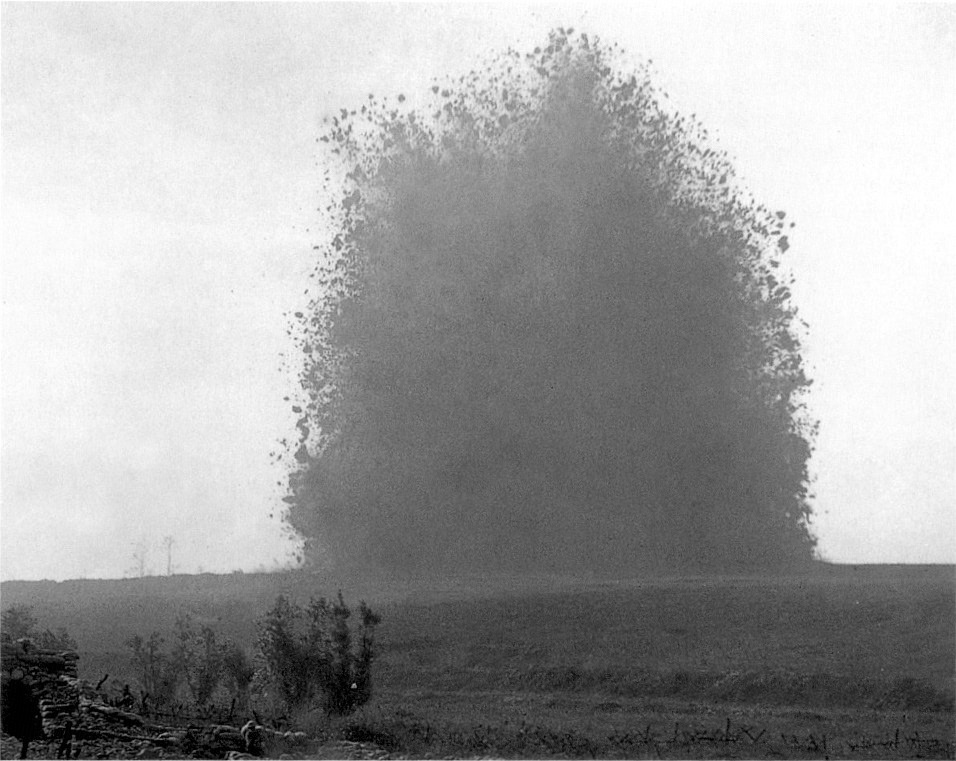

Hawthorn Ridge, Redoubt Mine, 1st July 1916

As the war progressed, Lansdowne, who lost his younger son Charlie, became convinced that the government’s knock-out blow strategy was unrealistic, and ‘he decided to act on his conviction in what became one of the most courageous moments of a long career built on independence and integrity in politics’ (p 281). One of Lansdowne’s finest hours, although it did not appear so at the time, came with the publication in the Daily Telegraph on 29th November 1917 of a long letter – today such a missive would be published as an article – which proposed that the government should enter into peace talks with the Central Powers. He feared that the continuation of the war would spell ruin to the civilised world. Reaction to the ‘Peace Letter’ was overwhelmingly negative: ‘overnight, Lansdowne became one of the most reviled men in England’ (p 292). As an aristocrat, he was not unduly bothered by this; he felt vindicated when Woodrow Wilson based his ‘Fourteen Points’ on his proposals. Unfortunately, his unappreciated intervention meant that he was not invited to participate at the Paris Peace Conference.

Lansdowne’s last years were clouded by the death of his son in WW1, and the loss of various of his properties. His Irish seat Derreen House, County Kerry, was burned down by the IRA in 1922, but rebuilt by 1925. Lansdowne House was let for £5000 pa to Gordon Selfridge, who stayed there until 1929, when Lansdowne’s son sold it. Much of it was later demolished, but the ballroom and other rooms remain in what is now the Lansdowne Club. The final reception at Lansdowne House was held in April 1920, for the wedding of Lansdowne’s granddaughter, Dorothy, to Harold Macmillan. With Lansdowne House leased, Lansdowne retreated to Bowood, where he died in 1927, aged 82.

The book contains some unfortunate errors. On p 68, we read that ‘on 3 January 1890 ‘Eddy’ Albert Victor, Prince of Wales, arrived at Calcutta’, at that time, the capital of India. Prince Albert Victor is correctly described as the Duke of Clarence in a caption to a photograph, which however dates his visit to Calcutta as 1892 (he died in January 1892). But he was never Prince of Wales – he died before his father ascended the throne as King Edward V11. The mistake is repeated on p 71. On p 225, likewise, Victor Devonshire, Lansdowne’s son-in-law, is described as his nephew. When writing of the composition of the House of Lords, Kerry says ‘Most were hereditary peers; only a third were life peers or bishops’ (186). But there were very few life peers (only the Law Lords) in the late nineteenth century; only after the Life Peerages Act 1963 did life peers enter the House in significant numbers. Sir Maurice (‘Bongie’) Bonham Carter is incorrectly nicknamed ‘Mongie’ (p 249).

These errors notwithstanding, this is an impressive tribute to a distinguished ancestor. It has been thoroughly researched in all the relevant archives in Britain, Canada, the US and Austria. It is illustrated with a wealth of photographs, both family and official. Lansdowne emerges as the best type of aristocrat: intelligent, cultured, competent, principled and conscientious. The absence of such men in contemporary Britain is a loss to us all.

Lansdowne House

Angela Ellis-Jones is a writer and researcher

Like this:

Like Loading...

Blessed are the Peacemakers

Marquess of Lansdowne

Blessed are the Peacemakers

Lansdowne; The Last Great Whig, Simon Kerry, Unicorn, 398pp, 2017, ISBN 978-1-910787-95-3, reviewed by Angela Ellis-Jones

This biography of Lord Lansdowne, one of late Victorian and Edwardian Britain’s most distinguished people, is written by the subject’s great-great grandson, who modestly omits to mention that he is the heir to the current Marquess. Lansdowne was born into the Whig aristocracy. The founder of the family fortune was Lansdowne’s four-times great grandfather, Sir William Petty (1623-87), the son of a clothier who began his working life as a cabin boy but subsequently enjoyed a brilliant polymathic career. After he had served as Professor of Anatomy at Oxford (1651-2) and of Music at Gresham College, London, a stint as physician to Cromwell’s army in Ireland led to his appointment as director of the land survey of Ireland for the purpose of dividing the spoils amongst Cromwell’s men. He finished the first complete map of Ireland in 1656, and amassed 270,000 acres of land in south Kerry alone. When he made his will in 1685, he calculated his annual income to be £15,000, an enormous sum at a time when the annual average was just short of £7!

Just as Petty was a member of a brilliant intellectual circle – he was a founder of the Royal Society – so also was his great-grandson, the second Lord Shelburne (1737-1805), who became the first Marquess of Lansdowne following his time as prime minister (1782-3), during which he negotiated the settlement of the American War of Independence. Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen while he held the position of librarian at Bowood. Bentham was a visitor to the house which Shelburne commissioned Robert Adam to decorate, and filled with beautiful paintings, furniture and sculpture. Shelburne’s son, Lansdowne’s grandfather, had been chancellor of the Exchequer at the age of 25, in 1806.

With such ancestors, Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, fifth Marquess of Lansdowne (1845-1927) was evidently well-endowed intellectually. The son of a half-French mother of distinguished lineage, he grew up bilingual. After he narrowly missed a First in Greats at Oxford, his tutor, the renowned Benjamin Jowett, commiserated: ‘You have certainly far greater ability than many First Classmen’ (Lord Newton, 1929, Lord Lansdowne, p 9). Jowett later saw him as prime ministerial material.

Having inherited his father’s titles and estates while at Oxford, great wealth did not corrupt him. Lansdowne, now head of one of the great Whig families, was offered a junior Lordship of the Treasury in Gladstone’s first government – at the age of nearly 24! Four years later he accepted the post of Under-Secretary of State for War. In 1880, he was appointed Under-Secretary of State for India, an office from which he soon resigned over Gladstone’s Irish Land Bill. His resignation, says Kerry, was ‘the first distinguished step of a career in which the defence of the landowning class against a threat from the left was to be a principal theme’ (p 28) He did not lack occupation in these years; one of his posts was that of chairman of the Joint Committee of the two Houses on the Channel Tunnel proposals.

As a prominent Anglo-Irish landlord and critic of government policy, Lansdowne was a threat to Gladstone, who may have wished to remove him from domestic politics. In 1883, he was appointed Governor General of Canada, an office he discharged with ‘unfailing dignity and polished grace’. This required great courage; Lansdowne’s status as an Irish landlord meant that the threat of assassination from Fenians was omnipresent. In 1888, on the suggestion of Queen Victoria, he was appointed Viceroy of India, the premier Imperial appointment. On his retirement from the viceroyalty in 1893, Victoria wished to offer him a dukedom, as she had offered one to his grandfather, but Gladstone vetoed it. Lansdowne was relieved, as he did not have the financial means to support a dukedom. Throughout his life, he was, like many of his class, asset-rich, cash-poor, and sold a succession of properties and paintings to make ends meet.

In 1869, Lansdowne married Lady Maud Hamilton, who bore him two sons and two daughters. Lady Maud was the daughter of the first Duke of Abercorn, Ireland’s premier peer, who was Lord Lieutenant (Viceroy) of Ireland on two occasions. The marriages of all of her six sisters to other peers meant that the Lansdownes were members of one of the largest aristocratic kinship networks; Lansdowne himself was extensively related to the Whig peerage. Lansdowne’s differences with Gladstone, and the fact that five of his six Hamilton brothers-in-law served as Conservative MPs, meant that he was increasingly drawn rightwards and, like most of the Whigs, left the Liberals to join the Liberal Unionists in 1886.

After his Viceroyalty ended, honours were showered upon him: the degree of DCL at Oxford, the Lord-Lieutenancy of his county (Wiltshire), the offer of the Embassy at St Petersburg. He was also made a Knight of the Garter. When Lord Salisbury became Prime Minister for the second time in 1895, he appointed Lansdowne War Secretary. In November 1900, when Salisbury decided that he could no longer continue as his own Foreign Secretary, Lansdowne succeeded him. Lansdowne gained plaudits for negotiating the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902, and the Entente Cordiale in 1904. When the Conservatives left office in 1905, Lansdowne, at any rate, could hold his head high.

On the deaths of Lord Salisbury in 1902 and Lord Goschen in 1907, Lansdowne was offered the position of Chancellor of Oxford University. On both occasions he declined this prestigious role. In 1903, he became the official leader of the Unionist Party in the House of Lords, a position he held until his retirement in December 1916, forced by the fact that Lloyd George did not invite him to join his wartime coalition.

As his earlier biographer, Lord Newton, wrote of him, he ‘represented the very finest type of what the old patrician system of this country could produce, for no one ever understood more fully the obligations of his class or lived more closely to the ideals expressed in the family motto “Virtute non verbis”’ (Newton, p 496).

In one of the most interesting chapters of the book, the author addresses the Unionist response to the Liberal landslide of 1906. From the late nineteenth century, differences between the House of Lords and Liberal governments had become increasingly salient. Lord Salisbury adopted what he called the referendal theory – the Lords’ duty was not to act as a pale shadow of the Commons but to represent the permanent feelings of the nation. Since the views of the Commons and the will of the people were not always consonant, the Lords had a duty to reject contentious bills. The government could then decide whether to call a general election on the issue. The best-known example of this was the Lords’ rejection of Gladstone’s second Home Rule Bill in 1893, for which there was clearly not a preponderance of support in the country. The resounding Unionist victory in the general election of 1895 was ascribed largely to the Unionist opposition to Home Rule, and totally vindicated the Lords’ stance.

Britain has never had a written constitution, so Conservative/Unionist views on many of its aspects coexisted alongside Liberal ones. The referendal theory of the House of Lords was matched by the Liberal view that the representative nature of the House of Commons meant that its views should prevail. To which the Conservatives replied that the voters choose one party offering many policies, and that not all of a party’s voters should be assumed to endorse all of its policies. Moreover, public opinion can change in the years following a general election. It is strange that Kerry concedes far more to his ancestor’s opponents than he needs to, stating ‘Lansdowne himself did not strictly adopt Salisbury’s referendal theory, but he and Balfour – in defiance of accepted parliamentary government – continued to invoke this theory to justify the Lords’ legislative veto’. The whole point is that their invocation of the referendal theory was not ‘in defiance of accepted parliamentary government’ – this was strongly contested at the time, and was not settled until the passage of the Parliament Act 1911. Indeed, if the Unionists had won the January 1910 general election, the referendal theory would have prevailed, and history would not have judged the Lords to have behaved ‘unconstitutionally’.

Starting from this false premise, Kerry criticises the stance that Lansdowne and Balfour took in relation to the Lloyd George budget. In Lloyd George and the Lords – the British Constitution in Crisis, I examined the episode from the viewpoint of the Lords which, because they lost, has never had a fair hearing. I disagree with Kerry’s characterisation of this episode as ‘a disastrous error.’ Rather, we need to ask why two such highly intelligent men as Balfour and Lansdowne took the course of action that they did. They were experienced politicians: both had moved in the highest political circles since their twenties. Balfour was considered to possess the subtlest political intelligence of his generation. By 1909, Lansdowne, according to Lord Newton, was “regarded as one of the best Parliamentarians of the day’ (Newton, p 457). Was this a case of clever men doing stupid things, as happens not infrequently? Or was there method in their ‘madness’? Anyone who reads their contributions to the various debates, especially Lansdowne’s of November 30, can see that they had good reasons for rejection.

Because the Budget clearly breached the conventions against ‘tacking’ (the inclusion of non-financial subject-matter), it was vindictively targeted at one section of the community, and its author gave plenty of hints that worse was to come. Balfour and Lansdowne saw the Budget as the critical battle for property in their time and that failure to resist would be a ‘cowardly betrayal’ of the interests they represented. A significant number of Liberal MPs and a majority of the Cabinet found the land taxes unacceptable; several of the latter expected that such a Budget would be rejected. For the Unionists, the Budget was the epitome of Socialism. The preservation of the traditional political, social and economic order depended on the survival of a strong Upper Chamber; it was about time that the House exercised its full powers, even in the controversial area of finance. As Balfour put it: ‘I do not see how the House of Lords could ever intervene usefully in the future if it accepts a deliberate slap in the face now’.

During the Great War, Lord and Lady Lansdowne contributed to the war effort. Lansdowne House became the HQ of the Officers’ Families Fund, set up by Lady Lansdowne in 1899, which had raised over £310,000 in 1916. Like many aristocratic ladies, Lady L ran a hospital for repatriated injured soldiers – starting with 20 beds at Bowood in September 1914, and, by the end of 1917, sixty. She was also involved with the British Red Cross Society.

Hawthorn Ridge, Redoubt Mine, 1st July 1916

As the war progressed, Lansdowne, who lost his younger son Charlie, became convinced that the government’s knock-out blow strategy was unrealistic, and ‘he decided to act on his conviction in what became one of the most courageous moments of a long career built on independence and integrity in politics’ (p 281). One of Lansdowne’s finest hours, although it did not appear so at the time, came with the publication in the Daily Telegraph on 29th November 1917 of a long letter – today such a missive would be published as an article – which proposed that the government should enter into peace talks with the Central Powers. He feared that the continuation of the war would spell ruin to the civilised world. Reaction to the ‘Peace Letter’ was overwhelmingly negative: ‘overnight, Lansdowne became one of the most reviled men in England’ (p 292). As an aristocrat, he was not unduly bothered by this; he felt vindicated when Woodrow Wilson based his ‘Fourteen Points’ on his proposals. Unfortunately, his unappreciated intervention meant that he was not invited to participate at the Paris Peace Conference.

Lansdowne’s last years were clouded by the death of his son in WW1, and the loss of various of his properties. His Irish seat Derreen House, County Kerry, was burned down by the IRA in 1922, but rebuilt by 1925. Lansdowne House was let for £5000 pa to Gordon Selfridge, who stayed there until 1929, when Lansdowne’s son sold it. Much of it was later demolished, but the ballroom and other rooms remain in what is now the Lansdowne Club. The final reception at Lansdowne House was held in April 1920, for the wedding of Lansdowne’s granddaughter, Dorothy, to Harold Macmillan. With Lansdowne House leased, Lansdowne retreated to Bowood, where he died in 1927, aged 82.

The book contains some unfortunate errors. On p 68, we read that ‘on 3 January 1890 ‘Eddy’ Albert Victor, Prince of Wales, arrived at Calcutta’, at that time, the capital of India. Prince Albert Victor is correctly described as the Duke of Clarence in a caption to a photograph, which however dates his visit to Calcutta as 1892 (he died in January 1892). But he was never Prince of Wales – he died before his father ascended the throne as King Edward V11. The mistake is repeated on p 71. On p 225, likewise, Victor Devonshire, Lansdowne’s son-in-law, is described as his nephew. When writing of the composition of the House of Lords, Kerry says ‘Most were hereditary peers; only a third were life peers or bishops’ (186). But there were very few life peers (only the Law Lords) in the late nineteenth century; only after the Life Peerages Act 1963 did life peers enter the House in significant numbers. Sir Maurice (‘Bongie’) Bonham Carter is incorrectly nicknamed ‘Mongie’ (p 249).

These errors notwithstanding, this is an impressive tribute to a distinguished ancestor. It has been thoroughly researched in all the relevant archives in Britain, Canada, the US and Austria. It is illustrated with a wealth of photographs, both family and official. Lansdowne emerges as the best type of aristocrat: intelligent, cultured, competent, principled and conscientious. The absence of such men in contemporary Britain is a loss to us all.

Lansdowne House

Angela Ellis-Jones is a writer and researcher

Share this:

Like this: