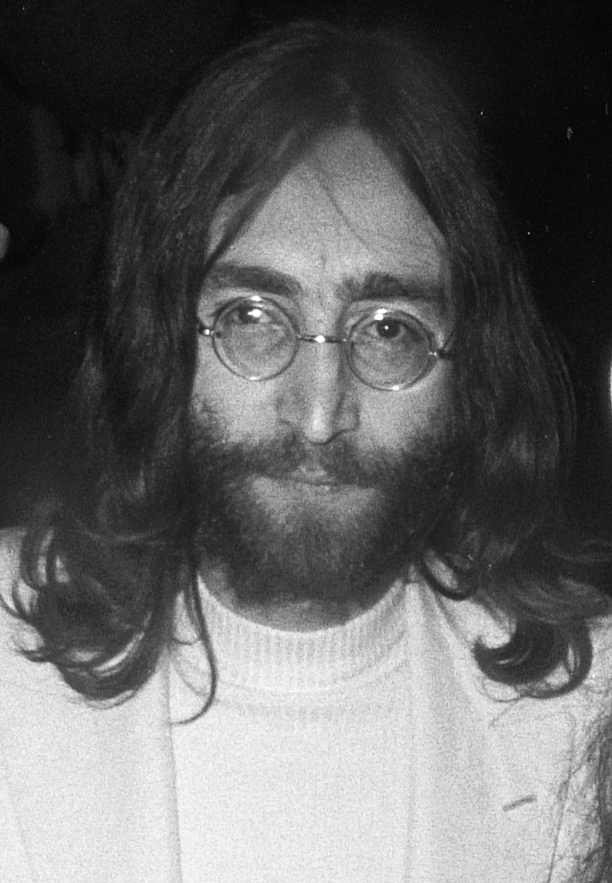

Viscount Haldane, credit Wikipedia

Architect of Final Victory

HALDANE, THE FORGOTTEN STATESMAN WHO SHAPED MODERN BRITAIN, by John Campbell, Hurst Publishers, ISBN 978-1-78738-311-1, £30, reviewed by ANGELA ELLIS-JONES

He has never featured in popular lists of Great Britons, and no statue of him has been erected. But Richard Burdon Haldane (1856-1928) could be considered, second only to Churchill, as the Greatest Briton of the C20th. John Campbell’s biography, many years in the making, does full justice to this impressive polymath and public servant.

The book is subtitled The Forgotten Statesman Who Shaped Modern Britain, and the prefatory quote reads: ‘si monumentum requiris, circumscpice’. Haldane was the architect of the modern British state, and his work on educational institutions and scientific and medical research continues to benefit us. As someone who was twice unlucky in love, and needed only four hours sleep, he had more time than most to devote to his many interests, and accomplished the work of several lifetimes.

Haldane was born into an upper-middle class Scottish family. His maternal great-great uncles, Lords Eldon and Stowell, were both distinguished lawyers. Eldon was a predecessor of Haldane as Lord Chancellor. Other relatives were distinguished scientists. His brother, a physiologist, became a Companion of Honour – one of the few honours that Haldane himself was not awarded. Continue reading

Food Men Chew

Vampire Bat feeding, credit Wikipedia

Food Men Chew

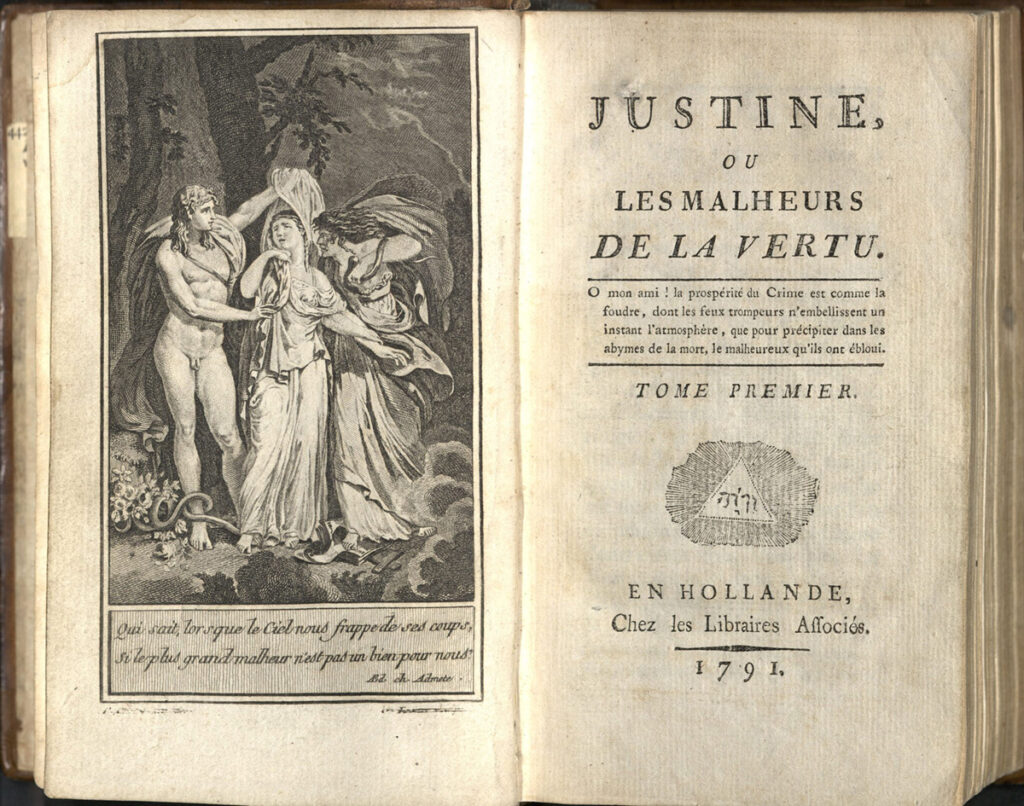

COVID – Ilana fingers the Chinese people

China’s plague-delivery pedigree is solid. Courtesy of China, the West got the H2N2 virus in 1957 and the H3N2 virus in 1968. Granted, the Chinese viral supply chain was broken with H1N1 flu; it came from Mexico. But, with the bird flu, SARS and SARS-Cov-2, China has reestablished its disease-delivery credentials. But going by the COVID culpability theories advanced by conservatives, the steady stream of “China plagues,” in Trump’s words, has had nothing to do with the noble Chinese people. Blame the ignoble Chinese Community Party for all these lethal, little RNA strands unleashed on the world. Some have even taken to calling SARS-CoV-2 “the CCP virus.”

As this Disneyfied neoconservative narrative goes, the Chinese were just hanging, being the freedom-loving, civilized sorts that they are; going about the business of making the world a better place, when, lo and behold, their scheming, communistic government sprung the COVID on them—and the world. Without fail, American pundits and pols, conservatives, in particular, apply to China the same theories of culpability that have undergirded America’s invasions of the illiberal people of the Middle East. The bifurcation globalists love is that of the noble Chinese people against the ignoble Chinese government. It’s the Chinese government, not the people. Liberate the Chinese and they’ll show their Jeffersonian propensity for enlightened self-interest, not to mention a palate for a cuisine less cruel. Continue reading →

Share this:

Like this: