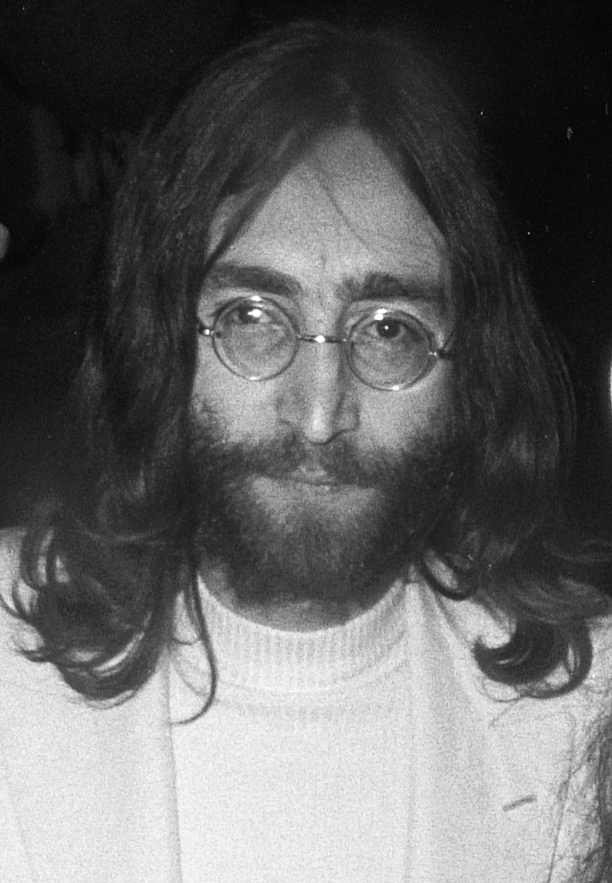

John Lennon, 1969, credit Wikipedia

Lives of Others

by Bill Hartley

One of the earliest examples of biographical writing is Plutarch’s Lives. Someone said that when it came to the amount of space he devoted to his subjects, Plutarch got it about right. For example, in the Everyman edition, Julius Caesar is covered in just fifty pages.

Whereas Plutarch was economical, some individuals are considered prominent enough to be the subject of more than one biography. One of the first attempts at giving John Lennon serious biographical treatment was a two volume work published in 2008, John Lennon: The Life, by Philip Norman. It helps, I suppose, if a biographer is interested in or likes his subject, although doubts about objectivity can then arise. In fairness, volume one, The Beatles Years, is fine. However, in the second, as one reviewer pointed out, the author evidently felt the need to gain the approval of his widow and the book comes perilously close to hagiography. Claims about Lennon’s post Beatles musical output are made that don’t withstand scrutiny. The same reviewer noted that it was as if the book had been written with Lennon’s widow looking over the author’s shoulder.

One can only imagine Yoko Ono’s reaction to Albert Goldman’s The Lives of John Lennon, which had appeared in 1988. The contrast with the later biography is extreme. This is definitely not a sympathetic treatment of the man. Indeed, some passages are jaw dropping. Whereas Norman appears to idolise Lennon, Goldman at times treats him with contempt. How did Lennon evolve into the strange and tortured creature depicted by Goldman? Little wonder that Goldman received death threats from outraged fans following publication. With two books presenting such different views, it seems possible that the definitive biography of Lennon remains to be written.

In contrast, there are certain individuals for whom the biography virtually writes itself, so larger than life and multi-talented is the subject. An obvious candidate for this description is Sir Richard Burton, soldier, explorer, linguist and scholar with a rather odd wife. This is a man who once found himself attacked by tribesmen on a beach in Somaliland and having received a spear through the face, removed it and continued the fight. Burton has received the attention of two biographers. In a review of The Devil Drives (1967), by Fawn Brodie, a ‘life of dazzling richness’ is referred to. Even that is close to an understatement. The alternative choice would be Snow Upon The Desert (1990), by Frank McLynn. Both books are equally good.

Whilst an on form Burton might be the ideal fantasy dinner party guest, Evelyn Waugh probably wouldn’t feature. Even HM Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother discovered how obnoxious he could be. This incident and many others are recounted in Selina Hastings’ Evelyn Waugh: A Biography (1994). The author manages to keep us consistently interested in a man whom one reviewer described as a ‘miserable rotter’. Waugh of course wasn’t the only ‘swine who could write well’ but the author manages to salvage some of the fun which can be found in his writing as she recounts his appalling snobbery, and often self-inflicted disasters. Out of his largely undistinguished military career came the wonderful Sword Of Honour trilogy. The Army, glad to see the back of him, gave him leave (in the midst of the Second World War!) to write Brideshead Revisited. Were it not for this biography then the best advice might be to experience Waugh only through his own writings.

There are individuals for whom a biography hardly seems necessary, since their life has been reduced to a single incident, evolving over time into a ridiculous caricature. In his book Custer’s Trials (2015), Pulitzer Prize winning author TJ Stiles sets out not so much to rescue the reputation of his subject but rather to reveal a fascinating, complex character born in the wrong era. A man who might have been more at home as a cavalry leader in the English Civil War rather than the American, when his lead from the front style was becoming outdated. Stiles tells a huge story against the background of a society undergoing traumatic change. He reveals Custer as a man who couldn’t adapt to his times; who freed countless slaves but paradoxically opposed new civil rights laws; who could lead but not manage. Interestingly, the book devotes little space to his demise. Stiles summarises the latter laconically, to wit, ‘Custer lost because the Indians won’.

Perhaps the worst view a reader can reach about a biography is that the subject is an uninteresting person who did interesting things. Beyond the Thirty Nine Steps (2019), by Ursula Buchan, isn’t a bad biography of John Buchan and one could never describe the man as lazy. If Buchan had a talent, whether writing or fly fishing, he was sure to make use of it. A likeable man who led a busy life, the biography scrupulously records all of his achievements. Sadly though there seems little of intrinsic interest in Buchan himself.

This is a trap into which a reader may easily fall. The subject achieved great success: therefore a biographer must have something interesting to tell us. Another recent example is The Lives of Lucien Freud (2019), by William Feaver. Reviews were uniformly gushing. Less so were the opinions of online reviewers. The first of two volumes (a massive piece of work running to a total of 600 pages), the author is well qualified to tell us about Freud the painter. Of the man we learn very little, other than the fact that he was largely self-absorbed and uncompaniable. One newspaper reviewer referred to Freud’s ‘wild dangerous youth’. The one thing he did which might fit that description was to sign on a Liverpool freighter for a wartime voyage across the Atlantic. After that he ducked war service in the country which had taken him in. The author makes no comment on this.

Throughout, the minutiae is astounding and also boring. We learn that Freud acquires a house. He plants two bay trees in the front garden. One dies. People we occasionally know but mostly don’t, flit in and out of its pages rather like a 1950s newspaper gossip column. If Freud had saved his bus tickets the author would probably have told us where he used them. The whole book is nicely summarised by one online reviewer who described it as ‘Freud’s own univestigated memories’, which barely qualifies as biography. Like the second Lennon biography, the author seems overly enthralled by his subject.

I did gain one piece of information from the book. The Freud painting I am most acquainted with is Interior At Paddington, in the Walker Art Gallery. The subject, seeing the finished picture, believed that his legs were too short. I too thought that that his legs were short. Freud explains that his legs were in fact that short – mystery solved.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Marxism-Lennonism, the ideology of British decadence?

One thing very noticeable, if not obvious, is the way in which successive biographies are determined by political prejudice in the selection of “for” and “against” material. The “Left” do not like revisionist studies of their pet heroes and pet hates, and their myths have to be restored and regurgitated.

To take two examples, Karl Marx & Joe McCarthy. One of the most devastating documented biographies of Old Whiskers, who used to cut off his boils with scissors and whose ideology was an “historical tsunami” that led to “dekamegamurders” (Steven Pinker), was Leopold Schwarzschild’s “Red Prussian”, but who has even heard of it? Larry Tye has written an attack on Senator McCarthy which briefly mentions but otherwise ignores the detailed defence of his inquiry into government subversion by M. Stanton Evans (sadly deceased 2015) and the content of studies like John T. Flynn’s “Lattimore Story”. There are still true believers in the innocence of Alger Hiss, the Rosenbergs, Oppenheimer and Roger Hollis.