Father to the Man

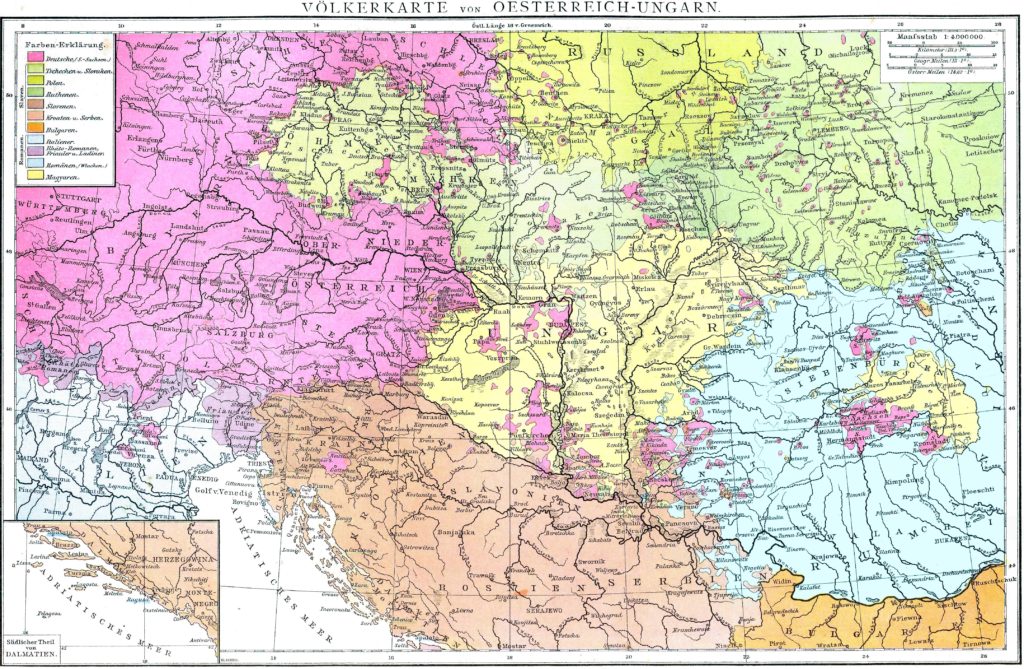

Ethnic Map of Austria-Hungary

The Confusions of Young Master Törless

by Robert Musil, translated by Christopher Moncrieff, Alma Classics, 2014, 250pp, pb, £6.39

STODDARD MARTIN reviews a new translation of Robert Musil’s Bildungsroman

In this year of the centenary of the start of World War I, the dinner-party topic du jour is: should we have fought, and who was to blame? The consensual answer, which ‘sound’ types are meant to agree, is the conventional one: Britain was noble to have devoted blood and treasure to a just cause (technically, the inviolability of Belgium), and the villain was German militarism. In this self-serving gloss, almost no one mentions that it was Russian mobilization that set the alliance-system dominoes falling or that the cause of that sudden show of force was Austro-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia and its belligerent reaction when the tiny neighbour didn’t immediately click heels in abject assent.Austro-Hungary was the sick man of Europe. Presided over by the octogenarian scion of a dynasty that had reigned over the heart of the continent far too long, it could hold together a fissiparous mass only by a bureaucracy best known via Kafka and a military whose pomp was in inverse proportion to its performance, from Sadowa back to Austerlitz. Even the puny Prussia of Frederick the Great had done rather well against it in the salad days of Maria Theresa. Cultural drift reflected this long goodbye in political dominance, with the brio of the age of Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert giving way to an era ‘when joy had become a subtle form of pain’ – Mahler, Schönberg, Berg, Webern and the decadence Richard Strauss so effectively rendered in music for the Salomé of Oscar Wilde (1906).

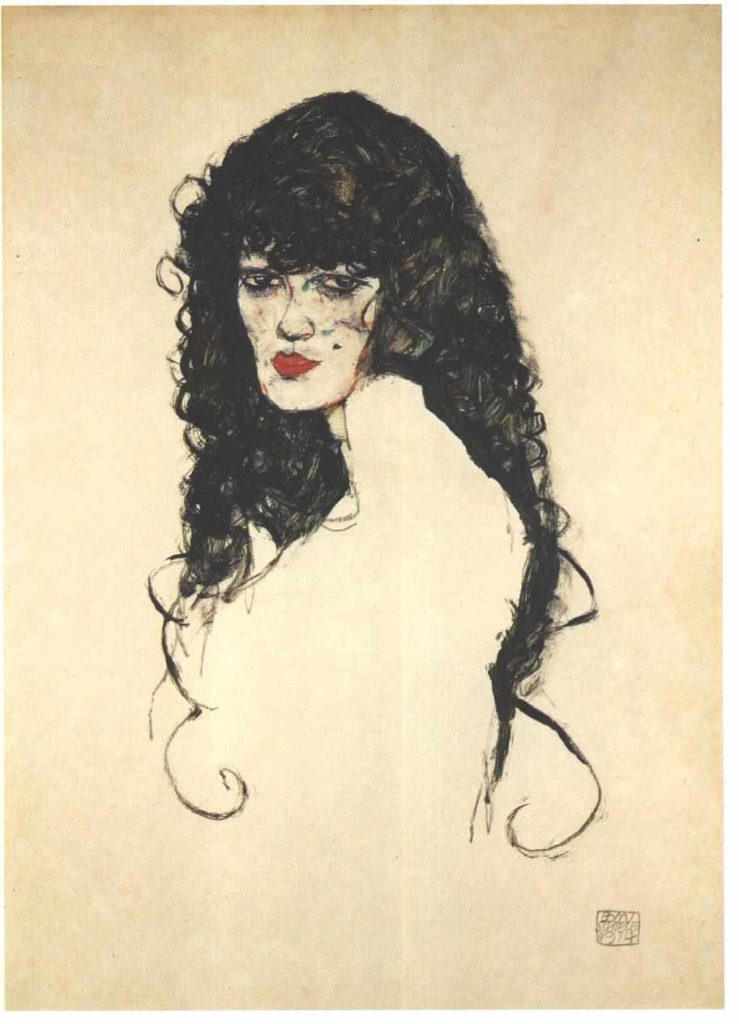

This pullulating period produced Secessionist artists specializing in borderline porn: the crypto-orgasmic females of Klimt, masturbatory self-images in Schiele. The prurient imaginings of Stefan Zweig reflected desires concealed behind the perfume of the bourgeoisie, so too endless discovery of sexual motivation beneath conduct recorded by Dr Freud. Vienna gave in to temptation and elected an anti-Semite mayor, mirroring its majority’s loathing for so many non-native-German speakers in its midst. Odium lurked beyond its favourite Strauss (Johann) waltzes until even the avant garde Strauss (Richard) was persuaded to change tune and glorify nostalgia in Der Rosenkavalier. This over-long swan-song for an epoch was produced in a year when Adolf Hitler was eking out his living selling painted postcards of quaint olden buildings. Vienna was rotten and Austro-Hungary already breaking up, though few would quite yet admit it. Soon all would turn worse – very much so: the ‘nation’ dismembered, its half-a-millennium-long monarchy deposed, the perverse delights of a Zweig giving way to the monstrosities of, say, Elias Canetti – Die Blendung (1935).

The greatest literary figure of this parlous place and time is seen by many as Robert Musil. His long, unfinished masterpiece Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften (The Man without Qualities) is often ranked with Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, Joyce’s Ulysses and Mann’s The Magic Mountain as a ‘book to go beyond all books’ of the era. Musil painted his world in intimate detail, recording its vices undauntedly, analyzing with profound curvature, using language like a master and tapping into that new-ish frontier – the inner life – with a candour that arguably surpassed that of his rivals. Like Joyce and the others his great work was preceded by a Bildungsroman exploring the young artist in embryo, or persona very like him – Proust’s Jean Santeuil, Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, Mann’s Tonio Kröger. Der Verwirrungen des Zöglings Törless – The Confusions of Young Master Törless as Musil’s 1906 work is entitled in its latest English translation – describes a crucial year in the life of a bureaucrat’s son at one of the empire’s élite academies. The milieu may seem familiar to English readers knowledgeable about public schools, from the playing fields of Eton on down. Yet the power struggles and sadism that Musil’s protagonist encounters will violate sensitivities of any still wedded to a roseate notion that schooldays are mainly an epoch of memorable fellowship and pastoral growth.

Schiele, Woman with Black Hair

Törless’s institution is far away in the country, an isolation meant to protect its students from urban vice. In fact, it is a perfect setting for worse. There is a village nearby, but the peasants who frequent its sole tavern are brutes; when not performing as work-beasts, they spend their time drinking themselves silly and abusing the local prostitute. The schoolboys evade these frightening males but visit the whore too, unsure of what to do with her but boasting otherwise. The most epicene of them, impecunious Basini, accumulates debts from his visits and services them by pilfering cash from his classmates’ lockers. A clique discovers his ‘crime’ and initiates a cycle of intimidation and blackmail in punishment, leading to repeated homosexual rape, beatings and torture. Törless is at first no more than an observer of these violations: he is a straight-arrow who was simply outraged by Basini’s theft. However, when the other boys are away on a long weekend, leaving him and Basini virtually alone at the school, a curious erotic attraction leads him into his own heartless liaison with the abused boy. A mixture of existential indifference and free-floating anxiety follows.

This plot is marked by graphic, occasionally lubricious descriptions that take it far beyond what the north German Mann had intimated in his homoerotic Tonio Kröger four years before or would in his more mature Tod in Venedig five years on. The latter shares in identifying temptation and downfall with the beauty of a teenage boy, an Italian penumbra behind him – Basini’s name, Mann’s novella’s location – yet revealed sex and its consummation are not even imagined. Nor are they importantly depicted in the début novel Joyce would begin in the Austro-Hungarian port of Trieste in the year of Törless’s publication. What A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man shares with Musil’s novella – Mann’s too in its ways – is a blending of philosophy and metaphysics into the account of moral awakening. In Joyce’s book these grow out of arguments with religion and nation and assume centre-stage, proceeding to a weighing-up of aesthetics as the way forward. In Törless similar arguments and weighing-up are opaque. Religion does not figure and nation is unmentioned, possibly because the ‘nation’ in which the action takes place is no more than a theoretical amalgam.

Its mélange may be reflected in the identities of the book’s principal characters – Reitling, Germanic, given to command, oratory and manipulation; Beineberg, possibly Jewish, given to science of mind, hypnosis, the occult; a Viennese prince; a Polish count; the indeterminate Törless; Galician peasants and of course the hapless Basini. Is it indicative that abuse is doled out to an apparent non-Austrian, incomer from one of the empire’s peripheral provinces? Do we have here intimation of the roles that the subject nations of Hapsburgia would play within a decade and their disintegrative effect? Törless, through whose eyes we see, does not interpret matters so portentously; but Musil’s intentions are subtle. He arranges his dramatis personae in such a way that the reader is likely to sense it as representing larger forces. At the least, the supporting characters embody fundamental tendencies of mind around which the relatively passive protagonist must find his own path. Yet try as he vaguely does, this young man cannot achieve firm direction. Törless remains a dreamer who is happiest when observing the infinite in passing clouds; who is fascinated by imaginary mathematics and the writings of Kant, without managing much true understanding of either.

This unsettling book, revolting at turns, is sinister in its power of seduction. In a useful afterword its new translator tells us that ‘much of [its] impact derives from Musil’s poetic and incisive prose’; he describes enthusiastically a style ‘littered with idioms from French and the many different national languages of the Empire – and Kanzleisprache, the intricately formal parlance of the omnipresent Austro-Hungarian bureaucracy’. Said bureaucracy is strangely absent as the terrible plot unfolds: again and again one wishes that some prefect or master would step in to prevent downright evil; yet none appears until the end, when Törless musters the guts to tell Basini to alert them. Meanwhile, the richness of language that the translator extols is not conveyed easily in English. He may be right that ‘the narrative often resembles a combination of an epic poem and a ministerial briefing document, leading us through a maze of subordinate clauses where foreign word

and phrases suddenly explode like fireworks’; yet foreign phrases are few in his version and fireworks, epic poetry and bureaucratese hard to discern. The style of subordinate clauses as presented either leaves us groping for meaning or is broken into shorter, more comprehensible sentences. Read the book in the original German, if you can, or at least with it alongside. Otherwise, you may suffer an antipathetic experience without consolation of a redeeming aesthetic brilliance.

Dr. STODDARD MARTIN is the author of numerous books on 19th and 20th century culture