“Motormouth” Megyn Meets her Match

Ilana Mercer reflects on the slugfest in Cleveland

It’s “R & R for Megyn Kelly,” the Fox News channel announced last week on its website, followed by a gooey note from Kelly herself. Why was FNC broadcasting the vacation schedule of the Golden Goose that henpecked Donald Trump? Had Kelly been licked into shape by Trump? Was she off to lick her wounds?

Since the testy exchange between Trump and Kelly, at the first prime-time Republican debate, in Cleveland, Ohio, the anchor’s eponymous TV show, “The Kelly File,” has covered the meteoric rise of Mr. Trump sparingly. Perhaps Kelly has come to view herself as a kingmaker. Perhaps she thinks that should she choose not to report about a newsmaker; he’ll somehow fade into obscurity.

Full disclosure: at first blush, I was impressed by the quality of Fox News’ journalism in Cleveland, writing too exuberantly that “the true stars of the debate were the ruthless, impartial, analytical” reporters. Better that Kelly be the one to ask foolish, fem-oriented questions of The Donald than future Dem moderators. It neutralizes the latter. Or so I reasoned.

Moreover, it’s indisputable that compared to previous presidential debates overrun as they were by Democrat journos—Kelly, Bret Baier and Chris Wallace did a good job.

No presidential debate should, however, be gauged by how it departs from debates in which questions such as these are posed:

“Senator Obama, how do you address those who say you’re not authentically black enough?”

“Senator Dodd, you’ve been in Congress more than 30 years. Can you honestly say you’re any different?”

“Congressman Kucinich, your supporters certainly say you are different. Even your critics would certainly say you are different … What do you have that Senators Clinton and Obama do not have?” [Wait a sec. I know the answer: a trophy wife.]

And how about this intellectually nimble follow-up?

“Senator Clinton, you were involved in that [how-am-I-different] question. I want to give you a chance to respond [to that how-am-I-different question].”

“Senator Obama, you were also involved in that [how-am-I-different] question, as well. Please respond.”

The final crushingly stupid question to the 1-trick donkeys debating, in the 2007 CNN/YouTube Democratic presidential debate, was this:

“Who was your favorite teacher and why, Senator Gravel?”

The “journalist” pounding the presidential candidates was jackass Anderson Cooper of CNN.

Before she beat a retreat, Kelly had assembled a studio audience of Republican establishmentarian, to whom she directed another leading question: she herself knew nobody who’d call a woman a pig or a dog. Could they say the same? Kelly was alluding to the litany she had directed at Trump during her Cleveland performance (where she had cast herself as leading lady).

Kelly: “You’ve called women you don’t like, ‘fat pigs,’ ‘dogs,’ ‘slobs,’ and ‘disgusting animals.”

Trump [in good humor]: “Only Rosie O’Donnell.”

Megyn [bare-fanged]: “No it wasn’t. For the record, it was well beyond Rosie O’Donnell. Your Twitter account has several disparaging comments about women’s looks. You once told a contestant on ‘Celebrity Apprentice’ it would be a pretty picture to see her on her knees. Does that sound to you like the temperament of a man we should elect as president?”

Still under the brain-addling spell of the Cooper-Candy-Crowley brain trust, I thought no less of Kelly for that dumbest of questions. Her anti-individualist, collectivist feminism is news to her fans, but not to me. Kelly’s vocabulary is of a piece with the nauseating vocabulary of third-wave feminism.

More irksome was the allusion to the dignity of The Office. A while ago, fancy pants Kelly joined Don Lemon (CNN), Cooper and Rachel Mad Cow to editorialize angrily at Obama for damaging the dignity of The Office. These celebrity journos were, in fact, green with envy over GloZell Green, a YouTube sensation to whom president Obama granted an interview. Good for him.

Our TV narcissists—they live not for the truth, but for a seat at the Annual White House Sycophant’s Supper, or alongside the smarmy Jon Stewart (or his unfunny South African replacement), or next to the titillaters of “The View,” or on the late-night shows—were jealous. Dented was the vanity of the egos in the anchor’s chair.

Besides which the American presidency was pimped out a longtime ago—well before the current POTUS and FLOTUS held soirees sporting disco balls and the half-nude, pelvis-grinding Beyoncé.

Kelly herself has fast succumbed to the female instinct to show-off, bare skin, flirt and wink. She now also regularly motormouths it over the occasional smart guest she entertains (correction: the one smart guest, Ann Coulter). At the same time, Kelly has dignified the tinnitus named Dana Perino with a daily slot as Delphic oracle.

Trump, on the other hand, has proven he can be trusted to beat up on the right women.

Exhibit A is Elizabeth Beck, a multitasking “attorney,” who once deposed Donald Trump while also waving her breast pump in his face, demanding to break for a breast-pumping session.

“You’re disgusting. You’re disgusting,” the busy billionaire blurted in disbelief. And she was. Still is. Accoutered for battle, Beck recently did the rounds on the networks. In addition to a mad glint in the eye, Beck brought to each broadcast a big bag packed with milking paraphernalia.

Had she cared about boundaries and propriety, Kelly would have asked Trump how he kept his cool during a legal deposition, with an (ostensible) professional, who insisted on bringing attention to her lactating breasts.

Writes Fred Reed, who regularly tracks our malevolent matriarchy’s “poor sense of social boundaries”:

“The United States has embarked, or been embarked, on a headlong rush into matriarchy, something never before attempted in a major country. Men remain numerically dominant in positions of power, yes, but their behavior and freedom are ever more constrained by the wishes of hostile women. The effects have been disastrous. They are likely to be more so. The control, or near control, extends all through society. Politicians are terrified of women. … The pathological egalitarianism of the age makes it career-ending to mention that women in fact are neither equal nor identical to men.”

Not quite in the league of Elizabeth Beck yet, Megyn Kelly was, nevertheless, in need of a dressing-down and a time-out.

Ilana Mercer is a paleolibertarian writer, based in the U.S. She pens WND’s longest-standing, exclusive paleolibertarian column, “Return to Reason.” She is a fellow at the Jerusalem Institute for Market Studies. Her latest book is “Into the Cannibal’s Pot: Lessons For America From Post-Apartheid South Africa.” Her website is www.IlanaMercer.com. She blogs at www.barelyablog.com Follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/IlanaMercer “Friend” her on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ilanamercer.libertarian

Polish Higher Education Today

Nicolaus Copernicus University, Torun

Polish Higher Education Today

Mark Wegierski makes some telling observations

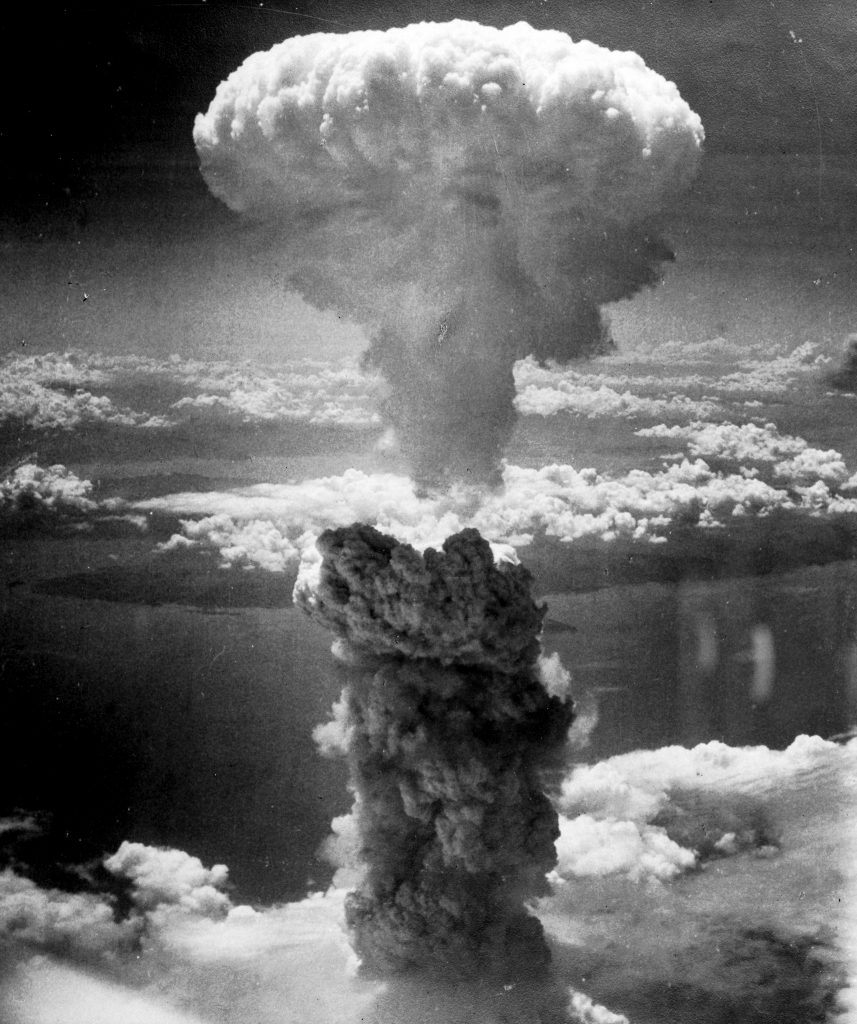

The Nicolaus Copernicus University (Uniwersytet Mikolaja Kopernika – UMK), was founded in 1945 in the wake of the Second World War in Torun, with many professors and researchers fleeing from the former Stefan Batory University in Wilno (Vilnius) – that area being swallowed into the Soviet Union, with the Stalin-mandated boundary shifts. The official date of the university’s founding is August 24, 1945, exactly 70 years ago this day.

There was a few years respite until the late 1940s, when Stalinism became ever more tightly enforced in Polish academic institutions, and in Polish society as a whole. It was only as a result of “The Thaw” after late 1956 (also sometimes called “the Polish October”) under the leadership of Wladyslaw Gomulka, that Stalinism was finally relaxed, and the Communist regime could be considered as “polonized”. While certain topics and themes were clearly “taboo”, the academic system was not harsh and grinding in the enforcement of Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy, as during the Stalinist period.

The crises of 1968-1970 profoundly affected the universities, but the Communist system was able to stabilize with the coming to power of Edward Gierek. Indeed, he inaugurated an era of “can do” spirit and relative prosperity. By the late 1970s, however, the situation had soured. During the Solidarity period of 1980-1981, there was a flowering of Polish academic and cultural life, with almost no one believing in Soviet Communism anymore. Indeed, it had to be enforced on Poland at the point of a gun (Communist General Jaruzelski’s declaration of martial law on December 13, 1981). 1989 was clearly another watershed, and, in the 1990s, there was an incredible expansion of higher education in Poland.

Indeed, the number of students attending public and private universities and colleges in Poland has been reaching ever-higher levels with every year. There has been an unprecedented boom in private colleges since the 1990s. Also, numerous State Higher Schools of Vocational Learning have been established. However, the ever-higher tuition costs for some studies (as well as the high costs of living in the major university towns), and high levels of poverty in Poland, may mean that above-average but not stellar students, from less affluent families, may not get the chance to attend university. There is also a major trend to “political correctness” and probably too much emphasis on E.U. guidelines in some institutions of higher learning, resulting in less and less Polish patriotic spirit. A parallel trend is the excessive stress on career-related business and technical studies, rather than on what could be seen as a better-rounded education in liberal arts such as philosophy, history, and literature (at least for part of one’s pre-professional studies).

I recall that on Friday, September 27, 2002, I had travelled with my female relative from Ciechocinek, the spa and resort town at which I was staying during the late summer and early autumn of 2002, southwestward to Lodz, the second-largest city in Poland. She drove a compact yet elegant Peugeot 206. Ciechocinek lies about two hundred kilometers northwest of Warsaw. She was going to pick up the formal graduation papers associated with the Master’s degree she had just completed, at the Wojskowa Akademia Medyczna (Military Medical Academy) in Lodz. There was some urgency to the matter, as the WAM was merging with another institution to become the Uniwersytet Medyczny (Medical University) in Lodz. The WAM had been open to civilian students for a number a years, and my relative had completed a Master’s in Public Health on a part-time basis. As we sat in the car in front of the guard-house entrance to the university, I recalled her complaints, in earlier telephone conversations, about the long trips to classes she had to take from the environs of Ciechocinek, where she lives, to Lodz, often in inclement weather.

The WAM campus consisted of several large buildings constructed in what I thought to be a 1920s, Neoclassical style. I still remember the pleasant sunshine and warm weather at the time of our trip there, on that day in September.

Among her other studies, my relative has completed a Licentiate (the Polish equivalent of a B.A.) in Cosmetology, at the “Rydygier” Medical Academy in Bydgoszcz, Poland. There was some controversy when that Medical Academy proposed to merge with UMK in Torun – since the city administration of Bydgoszcz had hoped that the “Rydygier” Medical Academy could have become part of a major new university in Bydgoszcz itself. Indeed, the “Rydygier” Medical Academy became the UMK’s Medical College. Nevertheless, a few years later, there was a major university established in Bydgoszcz – Uniwersytet Kazimierza Wielkiego (UKW) (University of King Casimir the Great).

Having reached Lodz, we then continued southward to Czestochowa, where most of my relative’s immediate family – including her mother, sister, and brother – live, in a fairly big house with a large yard, on the city’s outskirts. Driving around Czestochowa, we noticed the large, elegant building of the Akademia Polonijna (Polonia University), a major new private college, which is very well-regarded – as seen, for example, in its high place in the annual college rankings put out jointly by the large-circulation newspaper, Rzeczpospolita (The Republic) and Perspektywy (Perspectives), a major magazine for students. The Akademia Polonijna has set, as one of its missions, extensive cultural and scholarly interaction with persons of Polish descent living abroad, as well as documentation of the various cultural and patriotic achievements of the various “Polonia” communities. (“Polonia” is the term often used in the Polish language to describe Polish communities outside of Poland.)

Since we had arrived unannounced at her family’s house, we decided to go for supper to Zornica, an elegant restaurant (and inn) on the southern outskirts of Czestochowa, built in the style of the Goral (Polish Mountaineer) architecture. Although, at six P.M., the place was rather empty, my dish was nevertheless tasty, consisting of pork medallions baked with mountaineer cheese and mushrooms, along with spicy roast potatoes, on a bed of sauerkraut.

Zornica Restaurant

We went back to the house for tea and cake, and then started the long trip back to Ciechocinek at about 8 P.M. In a feat of driving I thought incredible, we got back to Ciechocinek somewhere after midnight.

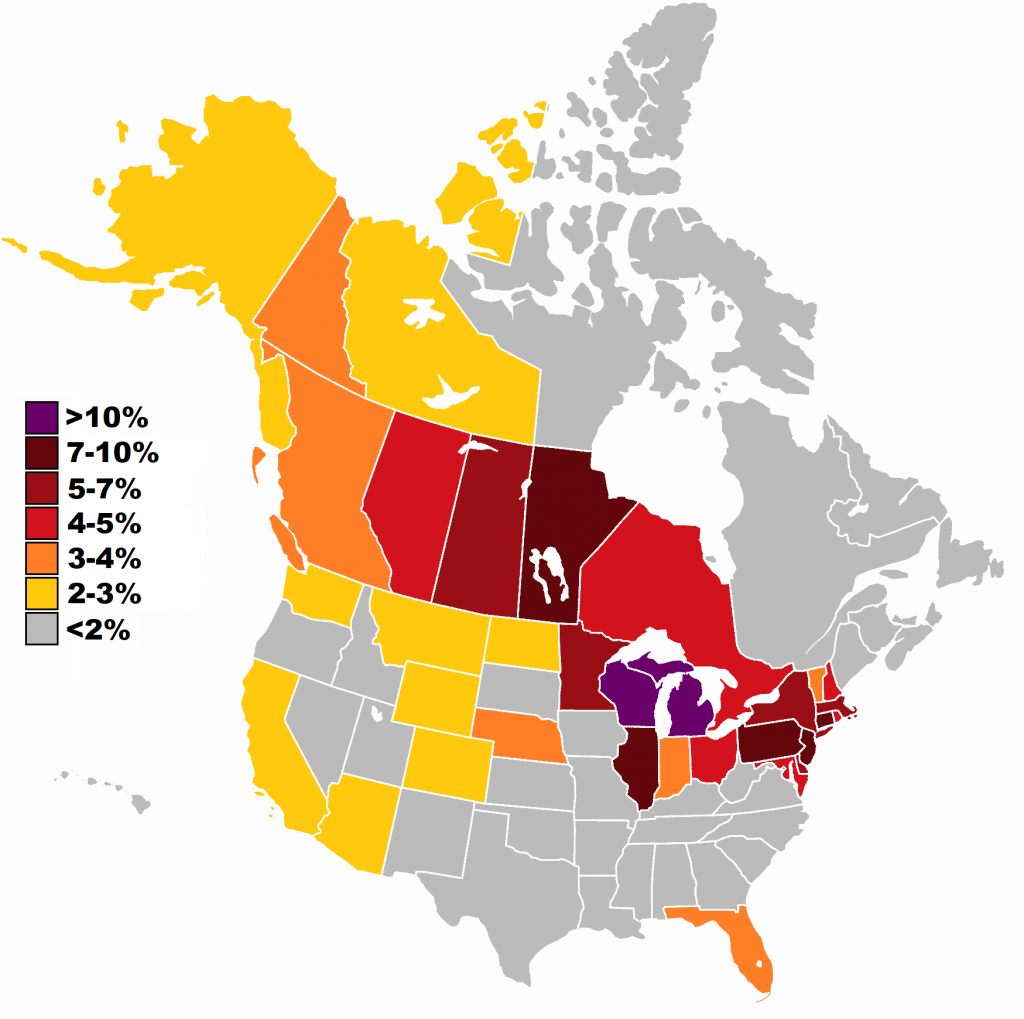

Many young people (as well as some persons in middle age) in Poland today, face the problem that, although they may in fact have very good training in a technical or business field, jobs for them simply don’t exist. The unemployed graduate of Management and Marketing studies in Poland is a virtual cliché. The nationwide average of unemployment was for many years around twenty percent, and was actually considerably higher for young people, and in certain regions, such as the southeast. And, in fact, two to three million Poles (especially younger people), have actually left since 2004, emigrating mostly to Great Britain, Ireland, and other E.U. countries. Those Polish politicians who can somehow improve the employment situation in Poland, in a way that will be sustainable over the long run, can expect to receive major support from the people of Poland.

Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and historical researcher

Share this:

Like this: