Acton Lane Remembered

Bill Hartley speaks truth to power

The Green Revolution in Britain is sustained by coal. Last year the country imported over 41,000,000 tonnes. The Port of Tyne that used to ship the stuff out has never been busier bringing it in: coals to Newcastle and much of this goes into our power stations.

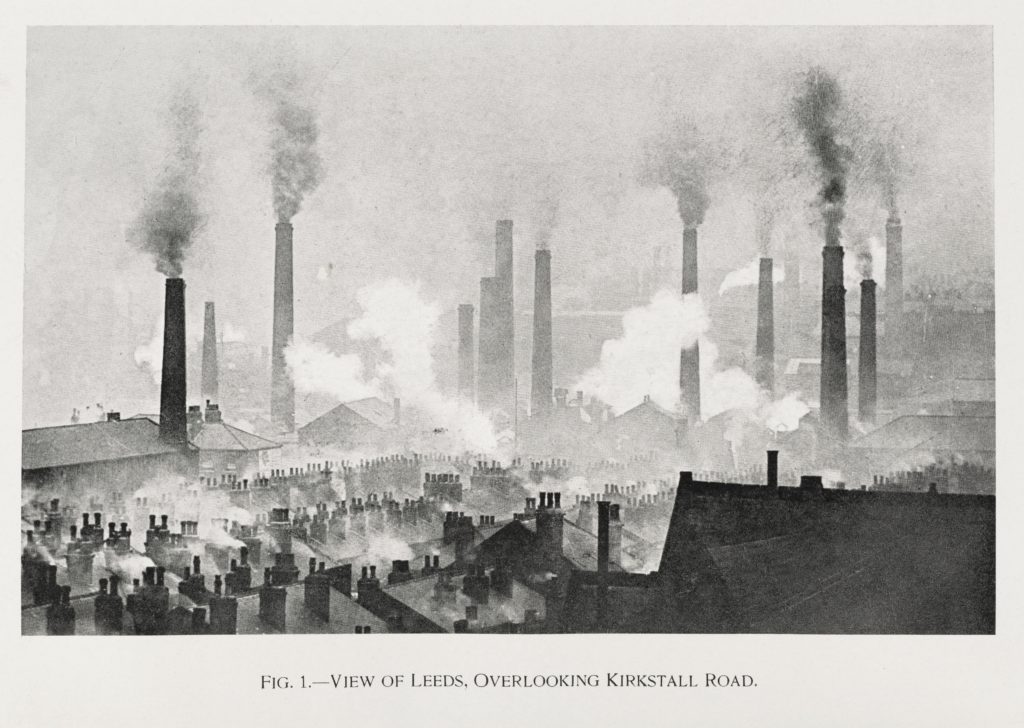

The late Keith Waterhouse once described his home town of Leeds as the ‘city of dreaming cooling towers’. Leeds Power Station was said to be the filthiest in the country and wind in the wrong direction could ruin a line of washing. Back then electricity generation was local. Any reasonably sized town or city had cooling towers on the horizon. Today the power station is mostly remote: confined to the flatlands of Yorkshire or housed in those sinister coastal buildings where the fuel source is nuclear.

View over Leeds, smoking chimneys

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk

Julius B. Cohen Published: 1912.

In the 1970s the network was still a nationalised industry and the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) had a couple of stations left working in London. Battersea was the best known but out in NW10 near the old Guinness Brewery at Park Royal was Acton Lane. This was a site dating back to the 1890s and the dawn of electricity generating.

The station had been a source of wonder when it opened in the early 1950s. Engineers came from all over Europe to marvel at the mighty turbines with a combined output of 150 mega watts and wondered if they would remain secured to the floor. By the early seventies though, Acton Lane was on its last legs. Technology had moved on and a station of enormous capacity back in the fifties had become a minnow. Acton Lane was now reduced to a back up role and curiously this meant it was a more hard worked station than those remote giants which now generate most of our electricity. The way to run such huge stations economically is to keep them on base load generating round the clock and shutting down only for essential maintenance. In contrast the workers at Acton Lane might expect to shut down and start up on a daily basis when the national grid needed extra power. And it wasn’t a push button operation. The conductors of this particular orchestra were the turbine drivers, the elite of generating staff. They controlled a workforce on three levels and due to the deafening roar communication was via sign language. Down in the basement were the humble plant attendants whose job it was to control the water supply. They roamed a level the size of a football field amidst a jungle of pipes leading to huge pumps that required regular inspection and lubrication. During those final years the pipe work was poorly maintained and an attendant might be obscured in dense clouds of drifting steam. His attention was attracted from the mezzanine above by striking the metal railings with a spanner. Essentially the turbine driver was signalling to report progress on raising revolutions. Were he to get it wrong then instead of superheated steam, water would enter the turbines and the effect on the blades would resemble a paddle steamer going down the Mississippi.

The turbine driver also managed the efforts of the men who ensured the boilers were kept fed. A conveyor belt of coal crushed to fine powder was fed into the furnaces and calories blasted from it with an induced draught. They were no mere factory boilers but monsters nearly ninety feet high. Climb vertiginous ladders to the top of these things and you entered a world where the air shimmered. Riyadh at noon would have seemed cool by comparison. It was an eerie place seldom visited. Beneath the catwalk, boilers literally groaned with the pent up pressure designed to turn water into superheated steam. Viewed from this vantage point it was easy to appreciate the alchemy of coal, fire and water, contained then harnessed by heavy engineering and transformed into electricity.

The process of going ‘on load’ could last for most of an eight hour shift until the control room signalled that the power had been accepted onto the grid. Then with the deafening roar of turbines making conversation impossible the order might come through to start the process of shutting down. It was difficult to imagine that anything worthwhile had been achieved but that was the role of Acton Lane in its dying days: topping up the grid, just in case the big stations were unable to fulfil the nation’s requirements.

The men who did this work had mostly begun their employment when the station opened. Like the plant they were reaching the end of their working lives. This was a breed of Londoner now all but extinct. They had been through the war, some as members of the Auxiliary Fire Service during the blitz. Others had seen service overseas and all had been glad to find work at the new power station. Back then London was still a place of manufacturing and this particular corner of the capital looked no different to any northern city. The Park Royal brewery was eventually to go however and with it most other industries. Acton Lane as their one time power source was just holding on.

During a stand down phase that could last for days at a time, only a handful of people were required to keep the plant ticking over. Everything slipped into slow motion: the bare minimum of coal being fed into the furnaces. The CEGB had an agreement with the unions whereby the workforce could be deployed on any duties during such periods. Several jobs might need to be done. For example if the flow of water from the nearby Grand Union Canal essential for cooling the feed pumps became reduced, then the reason was a blockage and workers were required to go out in a boat to investigate. Doubtless Health and Safety would these days have something to say about two men in a flimsy boat using rakes to recover a sodden mattress or occasionally something rather more ghastly.

A more sought after role was in the coal yard. Connected to the London- Birmingham main line Acton Lane got its fuel the old fashioned way and hauled it to the station using the last working steam locomotive in the capital. Little Barford as it was named can still be found chugging away on the North Norfolk Railway. It gave power station workers the occasional chance to play on their own railway for a day, learning how to uncouple coal wagons using a shunter’s hook. Get that wrong and a back sprain was the likely outcome.

The cooling towers of Acton Lane were one of the last landmarks of industrial North London. Unlike Battersea where the design meant there was a desire to save the building, nothing of the station remains following closure in the early eighties. The generating hall did live on for a few years though. You may even have seen it. The interior of the space freighter in Alien was in fact Acton Lane as was the Anvil Chemical works in the first Batman picture.

We hear much talk these days of renewable energy such as wind power. Renewables though can be unreliable and coal is still needed when those windmills are standing idle. Because a thermal power station cannot be switched on and off as required, coal has to be burned around the clock to make alternative energy sources possible. Like Acton Lane the traditional power station is still the back up.

BILL HARTLEY is a freelance writer from Yorkshire

An interesting piece. This England magazine has an article (in its Cornucopia section) all about the old Victorian water-pumping works in Shortlands, Kent – a piece of “industrial” history. The building is, in effect, a Victorian folly: a works disguised by a ragstone-built chateau-like construction.

I enjoyed time there for a few years back in the mid 60’s, a great post apprentice experience and served me well for my engineering career.