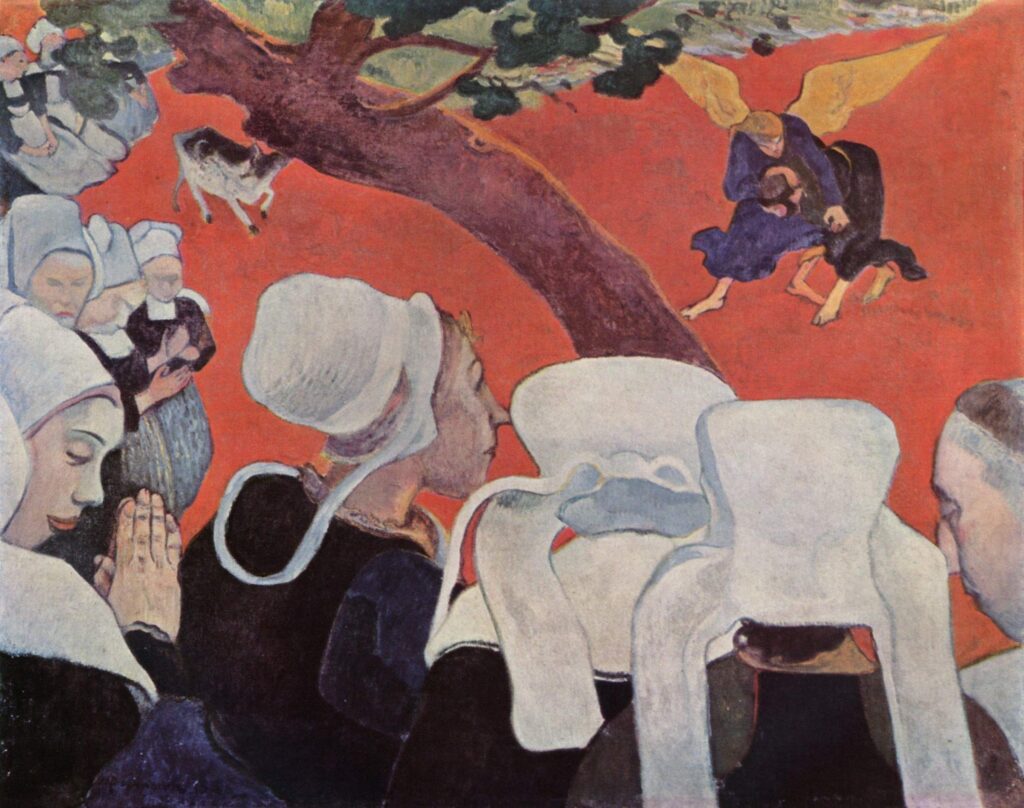

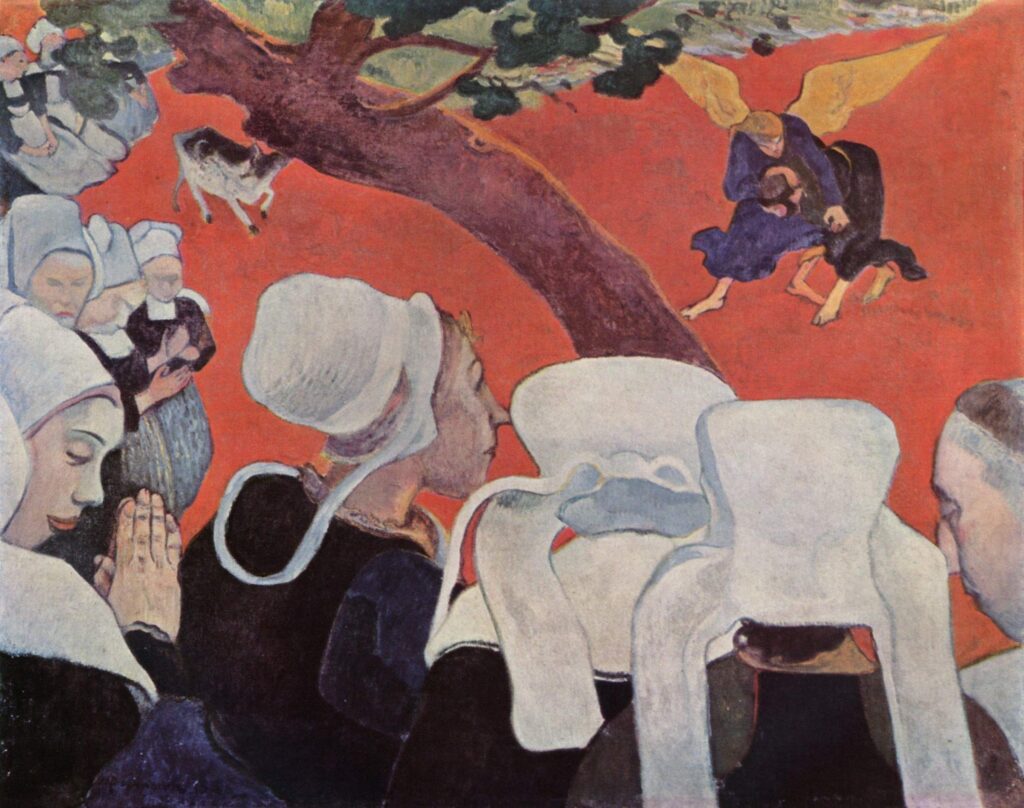

Paul Gauguin, The Vision of the Sermon, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1888

credit Wikipedia

Pauline Conversion

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, National Gallery, 22nd March 2023, curated by MaryAnne Stevens; After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, Catalogue of the Exhibition, National Gallery Global, 2023, reviewed by Leslie Jones

After Impressionism covers the supposedly pivotal period from 1886 (the date of the eighth and last Impressionist Exhibition in Paris) to 1914. The curator MaryAnne Stevens maintains that modern art was invented in this era and that a key factor here was the transition to “…non-naturalism, albeit expressed in various degrees from a modest distortion of reality to pure abstraction”. New painting techniques were developed and the artistic ideals of Greece and Rome that had informed the French academic tradition took a battering. Contemporaneously, there was what historian of ideas H Stuart Hughes called “the revolt against Positivism” (see his Consciousness and Society, 1958).

Paul Gauguin was emblematic in this context. Like Thomas Carlyle, author of On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841), Gauguin thought that “artists, like priests, were individuals with special powers…”, who gave “physical form to great ideas”. The Vision of the Sermon, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1888) symbolises a man, possibly Gauguin himself, fighting with his inner demons. Abandoning perspective, Gauguin believed that the aesthetic quality of a painting should “…no longer be measured by the accuracy of its representation of the natural world” (Stevens, Catalogue). In the still life Fête Gloanec, (1888), an assemblage of objects “appears to float rather than sit on the round table”. In The Wave (1888), the horizon is eliminated and the genre of the landscape painting thereby subverted. In Paul Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire (1902-6), likewise, recession is negated “through horizontal bands of colour”. And, in his portrait of his wife Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1888-90), there is an emphasis on the “rectangular forms of the chair back, fireplace and mirror frame”. The dress itself, on closer inspection, seems “insubstantial, not solid”.

Continue reading →

Like this:

Like Loading...