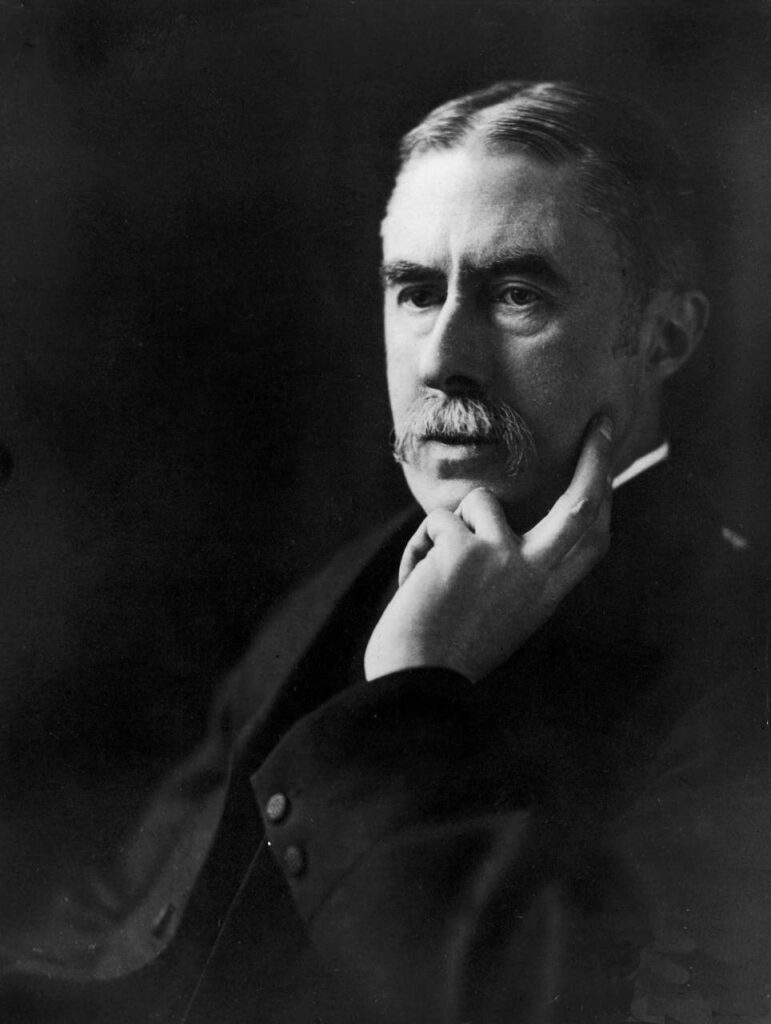

William Waldegrave in 1981

Vaulting Ambition, Thwarted

ANGELA ELLIS-JONES reviews a timely political memoir

A Different Kind of Weather, WILLIAM WALDEGRAVE, 2015, Constable, ISBN 978-1-4721-1975-9, £20

As an undergraduate at Oxford in the late 1970s, on visits to the Union I enjoyed looking at the photographs on the wall of past Presidents and their committees. One in particular caught my attention: Trinity Term, 1968. The President was a handsome young man, the Hon. William Waldegrave, who was flanked by the Queen (on her one and only visit to the Union) and Sir Harold Macmillan. After Waldegrave had been elected to Parliament as MP for Bristol West in 1979, he came to speak to the University Conservative Association. I assumed that he would become the next Conservative leader but one (he is a generation younger than Thatcher), and then Prime Minister. Never could I have imagined how things would turn out!

And neither could he. Published eighteen years after the author retired from politics (coincidentally the same amount of time he spent as an MP), this book is ‘an attempt to explain how things felt, to describe the weather of a life’. How it felt to have held the ambition to be Prime Minister for so long, then to be bitterly disappointed.

The memoir begins with an evocation of the Christmases of William’s very happy childhood at Chewton House in the village of Chewton Mendip in Somerset, ‘a world we have lost’. He was born in 1946, the youngest of seven children of the twelfth Earl and Countess Waldegrave. His mother, who had won a scholarship to read History at Somerville College, Oxford, had left before graduating, to get married in 1930.The Waldegraves had five daughters, followed by two sons. Much is made by psychologists of birth order as an influence on character. Did being the youngest (by six years) give William a burning determination to make his mark on the world, to be noticed? ‘And what better way than by becoming the most famous person in the world, applauded by all?’ At the age of fifteen, his free-floating ambition crystallised: he decided that he would be Prime Minister.

In the early Sixties, this appeared to be a perfectly realistic ambition. The patricians were still in charge of the Conservative party. The Waldegraves had been part of the ruling class for eight centuries. Walpole was an ancestor. William’s maternal grandmother, Hilda Lyttelton, was related to ‘half the intellectual and governmental elite of Victorian and Edwardian England’. And William himself evidently had a brilliant mind. As a child he read voraciously, excelled at Classics at his Prep School, and entered Eton as an Oppidan Scholar. After an intellectually omnivorous time at Eton, ranging over arts and sciences, a scholarship to Corpus Christi College Oxford followed. He was aware that he was living in a world that was on the cusp of change: ‘I arrived at the end of a culture and a social system that would not have been wholly unrecognisable in 1555, 1655, 1755, let alone 1855….No sooner had I mastered Virgil, Horace, Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides than they disappeared as the central reference points for educated discourse that they had been since the Renaissance’. His attitude to these changes was schizophrenic: ‘On the one hand, I loved the old culture; on the other I celebrated the radicalism of those who set out to destroy it’.

After taking an uncharacteristic Second in Mods, he made up for it with a congratulated First in Greats. He overcame his shyness to become President of the Union. He was also President of the Conservative Association. Waldegrave won most of the glittering prizes at Oxford, although he doesn’t appear to have captained a University Challenge team. After Oxford, he went to Harvard as a Kennedy Scholar to study political philosophy, a subject which was moribund at Oxford at that time, obsessed as it was with dry-as-dust linguistic philosophy. The following year, in 1971, he won a prize fellowship at All Souls’ College, the very acme of academic distinction.

By this time, he had embarked on his first job, in Lord Rothschild’s Central Policy Review Staff or ‘Think Tank’. Although he obtained this employment through his father’s connections in the House of Lords, he certainly deserved it on the basis of his academic record. Association with Rothschild enabled him to meet some of the most interesting people of the time – Nobel Prize winners, heads of Oxbridge colleges, inter al – and he soon became engaged to Rothschild’s daughter, Victoria. For Waldegrave, ‘Rothschild provided a dramatic embodiment of the perpetual search that partly drove my ambition: here was the romance of the mystery at the heart of the state; here were the people who knew the meanings of the nods and the winks which signalled that the world was not what it seemed’. However, having (via the Rothschilds) the likes of the hard–left Barbara Wootton, who exercised a very malign influence on postwar Britain (she should have been included in Quentin Letts’ ‘Fifty People Who Buggered Up Britain’) as ‘my tutor in penal policy’ doesn’t seem to have been an entirely suitable preparation for a Conservative MP!

In autumn 1973 Waldegrave left the civil service to become political secretary to Edward Heath, succeeding Douglas Hurd who had been selected to fight Mid-Oxfordshire (which became Witney in 1983). He remained in post until Margaret Thatcher became Conservative leader in January 1975. Rejecting Henry Keswick’s offer of the political editorship of The Spectator, he went to work for Arnold Weinstock, MD of GEC, then the largest private sector company in Britain. This would ‘allow my princely education to continue: I needed to know about industry and the real world’. In his spare time he wrote The Binding of Leviathan, which was published to great acclaim in 1978. Described on the dust-jacket as ‘an attempt to restate the fundamental moral and intellectual basis of Conservatism’, it predicted the imminent collapse of the Soviet Union. The following year he was elected to Parliament for Bristol West, twelve miles away from Chewton Mendip.

Anyone who is in any doubt as to the relative merits of Thatcher and Heath as people should consider this: whereas Waldegrave’s close association with Heath did not deter Thatcher from appointing him a Minister in 1981 (parliamentary secretary for higher education) upon this appointment, Heath refused to speak to him for several years! Waldegrave remained in office continuously in a variety of Ministries until the accession of the Blair government in 1997. The job he most enjoyed was that of Minister of State at the Foreign Office from 1988 to 1990.This coincided with the world-historical event of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the liberation of Eastern Europe. For his work in this area, Pope John Paul 11 wished to make him a Papal Knight; Waldegrave was furious when the Foreign Office refused the honour without consulting him. But this fascinating job nearly ended in fatality. In September 1990 he was scheduled to address a meeting of senior counter-terrorism experts from Britain and its main allies at the Royal Overseas League: ‘The IRA had hidden a large Semtex bomb in the lectern from which I was to have spoken. It was discovered by accident. If it had gone off, it would certainly have killed me as well as many others in the audience’.

He cannot have been the only politician at this time to have had such a lucky escape. In 1979 and 1990 two Conservative MPs were murdered, and five people lost their lives in the Brighton hotel bomb, designed to assassinate Margaret Thatcher, in 1984. Whatever else one may think of the politicians of this era, they were brave people: death was an omnipresent threat.

Shortly after this, Thatcher appointed Waldegrave to the Cabinet as Secretary of State for Health; he turned out to be her last appointment before her fall. Unlike some others, Waldegrave emerges honourably from an event which he describes as a ‘tragedy’ and a ‘shameful period’: ‘Such a figure should only ever be defeated by the electorate…there was something unfitting, wrong, about a party that owed one person so much, disposing of her in such a callous way’. Although he was initially not much in sympathy with Thatcherism, the proven success of her policies made him rethink some of his earlier views, and he records his pride at having served in her governments.

One can only sympathise with how Waldegrave must have felt when John Major became Prime Minister. For a former President of the Oxford Union, and Fellow of All Souls, the scion of a distinguished family, to have been put in the shade by a nonentity who left school with three O Levels must have been both painful and infuriating. The cruel bouleversement of what many people would consider to be the two men’s rightful positions was doubtless understood by Private Eye when they lampooned Waldegrave as ‘the man who makes the tea’. His comment on the situation is terse: ‘I had become used to Chris Patten beating me in our generation, but John Major?’

Major was only in a position to run for the leadership because of Thatcher’s spectacularly bad judgment of people, a characteristic which has become more plainly apparent since her death, with the revelations about her appointment of the pederast Peter Morrison MP to be Deputy Chairman of the Party and later her PPS, and her insistence on a knighthood for Jimmy Savile, despite strong warnings in both cases. (A more competent man than Morrison as campaign manager would have ensured that Thatcher remained leader in 1990). Thatcher, inexplicably thinking that Major was ‘one of us’, appointed him in quick succession Foreign Secretary, then Chancellor in 1989; clear evidence that her premiership was in its death-throes. She could so easily have appointed the FCO’s highly-regarded Minister of State to the top job; he would then have been in a position to stand for the leadership in1990. Instead, the Foreign Office was lumbered with a man to whom officials had to point out places on maps! And Treasury officials were doubtless shocked to discover that the custodian of the nation’s finances had left school having failed O Level Maths! As Chancellor, Major insisted on joining the ERM; the Treasury estimated the cost to the taxpayer of the ensuing debacle at £3.5 billion.

The 1990 contest was one of the most dispiriting Conservative leadership contests I can remember. Douglas Hurd, by a long way the ablest candidate, was considered unsuitable precisely because he had attended the best school in the country. Major, the epitome of ordinariness, was considered to be the ‘meritocratic’ candidate; one wondered why Hurd’s First from Cambridge and first place in the Foreign Office entrance examination were not considered strong evidence of merit. The fact that Hurd’s father had been a life peer (after a career as a Conservative MP) was also held against him. The son of a hereditary peer would have been persona even more non grata.

From the 1990 leadership contest, it looked as if nobody in the traditional Tory leader mould – upper-class background, top public school, Oxbridge – would ever again have a chance of leading the party. But would Waldegrave have been any more successful as PM than Major?

He certainly wouldn’t have been the international laughing-stock that Major became – perhaps the only good thing about the Major years was that they showed how important a good education is for a Premier. It would have been uplifting for Britain to have a Prime Minister in the tradition of the great scholar-statesmen of the Victorian and Edwardian era: Gladstone, Salisbury, Balfour, Rosebery, Asquith, Haldane, Curzon, and many others. (Waldegrave is even distantly related to Gladstone: his grandmother, Hilda Lyttelton, was the grand-daughter of Mrs Gladstone’s sister, and several of her Lyttelton aunts and uncles were close friends of Balfour.) And Waldegrave would not have presided over the polytechnics becoming ‘universities’, one of Major’s worst policy mistakes. But from the time of the Falklands War, when he saw Thatcher’s ‘capacity to withstand the relentless pressure that never leaves the holder of the highest office’, he ‘had to recognise that I could not have done what she did’.

Not that Major was any tougher. But one of the worst things about Major, together with his obvious inadequacy and unsuitability for the role, was his social liberalism. Waldegrave would have been happy to lead a socially liberal party: ‘In general, I shared the views of Chris Patten, Ian Gilmour, Roy Jenkins and Jo Grimond on how to live’. How to live? John Campbell’s recent biography of Jenkins, the godfather of the permissive society, has confirmed what many suspected: that the well-lunched Welshman helped himself liberally to the baronet’s wife, too. Jaded Whigs, with a hole in their heads where a moral sense should be! Nowhere in these memoirs is there any recognition of the cost, both social and financial, of amoral, nonjudgmental liberalism. The annual bill for family breakdown is estimated at £46 billion. Add many millions more for the cost of drug addiction. Waldegrave’s judgement, usually so sound, is woefully deficient in this area.

From the time he entered Parliament in 1979, Waldegrave was identified with the ‘Wets’, the name Thatcher gave to the Heathite liberal Conservatives. Their slogan was ‘One Nation’ and their hero was the unprincipled adventurer Disraeli. How an outlook first popularised in the 1830s could be useful 150 years later in a vastly changed society was never explained. ‘One Nation’ conservatism was devised for a society in which the Christian ethic was still widespread, and in which noblesse oblige and deference bound the different strata of society in mutual obligation. In a society from which deference had disappeared and in which the lower classes stridently insisted on their rights, fresh thinking was required. But the Wets’ judgment was distorted by upper-class guilt, which even Wets who came from a lower social stratum, like Heath, seemed to share. Middle class people resented the fact that, whereas the working classes had the Labour party to fight their corner, the ‘Conservative’ party under Macmillan and Heath and their cronies refused to champion middle-class interests. They also resented the Wets’ patronising attitude to anyone who disagreed with them.

The ‘depressed and depressing country’ (Waldegrave’s phrase) that Britain was in the 1970s was the world the Wets made (with some help from Harold Wilson). J S Mill referred to the Tory party of his day as the ‘stupid party’. Later, this would be a richly-deserved epithet for a party in which the Wets were in charge. What strikes one above all about the Wets is how wrong they were on just about every issue. Firstly, they were wrong on economics. They rejected the free market in favour of corporatism. In 1973 Lord Rothschild predicted that Britain would be half as rich per capita as France and Germany by 2000. Waldegrave acknowledges that without the intervention of Thatcher, this would indeed have happened. Secondly, they were wrong on Europe. Many Wets didn’t understand the constitutional issues, and those who did sought to deceive the British people into thinking that massive transfers of sovereignty were nothing to worry about at all. Waldegrave saw the constitutional issues far more clearly than many of his Wet friends did: pooled ‘sovereignty was a meaningless slogan’. To his credit, he refused to campaign for a ‘Yes’ vote in the 1975 Referendum. Thirdly, they were wrong on the Euro. Arch-Wets Heseltine and Clarke made complete fools of themselves advocating British entry, a position which no reputable economist could be found to endorse. Fourthly, they were wrong on the trade unions. The Wets couldn’t countenance alienating the unions, which were seen as part of Britain’s corporatist settlement. The Wet Jim Prior, Thatcher’s first employment secretary, introduced very limited legislation to bring the unions within the law in 1980. It required Norman Tebbit to finish the job, thus ushering in decades of peaceful industrial relations. Finally, they were wrong on immigration. The Wets expressed dismay about restricting immigration in response to pressure from voters who, unlike the Wets, were actually affected by competition for jobs and housing.

On all of these issues, except possibly for the last, Waldegrave was on the side of the Thatcherites. Yet he gives the impression that although he inclined to Thatcher with his head – how could he not? – his heart is still with the Wets. Nowhere does he mount a sustained critique of their errors.

One of the most depressing aspects of the Major years was the plummeting of standards in state schools, ably documented by Melanie Phillips in All Must Have Prizes (1996). Things must have been pretty bad for Blair to make ‘Education, Education, Education’ his mantra. The main reason for this situation was comprehensive education, and in particular, mixed ability teaching – two forms of social liberalism that no proper conservative could ever endorse. Yet a leading Wet of the Heath era, Old Etonian Edward Boyle (another candidate for Letts’s ‘Fifty People…’) campaigned for the Conservatives to commit themselves to a policy of replacing grammar and secondary modern schools with comprehensives.

It is surprising that nowhere in this memoir does this very academically-oriented politician tell us where he stood on the issue of grammar schools versus comprehensives. Nor does he make any observation on the parlous quality of the education which the great majority of his constituents’ children had to endure in the 1990s – and what he might have done about it if he had become PM. Indeed, surprisingly for someone who was consumed since his teens with the ambition to be Prime Minister, he doesn’t say much about what he would have done in any policy area if he had become PM. One would have expected a sustained critique of Major’s failings, but Waldegrave is silent. Although he was grateful to Major for keeping him in the Cabinet after he had made disparaging remarks about him when he became PM, surely at a distance of over twenty years he should now feel free to speak his mind? It would also be interesting to know what he thinks about the way Britain has developed over the past half-century – what, in his view, are the gains and the losses?

In a chapter entitled ‘Falling off a Precipice’, Waldegrave describes the trauma of losing Bristol West – which had never been anything other than Conservative, and which he had won in 1979 with over 50% of the vote – in the 1997 Labour landslide. Unlike some ‘retread’ MPs who re-enter the House of Commons at a subsequent General Election, he did not try again; he could see now that he would never achieve his cherished ambition. He was still only fifty, and accepted alternative employment in the City, becoming a Vice-Chairman of a major bank. He has some harsh criticisms of the way many individuals and institutions in the City operated: ‘The new ethos was totally fee driven, ruthlessly selfish, disloyal to employers’. Concurrently with his work in the City, he became Chairman of the Science Museum, and Chairman of the Rhodes Trust, both for nearly a decade. In 2009, he became Provost of Eton College. A life peer, Baron Waldegrave of North Hill, since 1999, he has not, on the evidence of this memoir, been a particularly active member of the upper House. He modestly refrains from mentioning all the outfits of which he has been a director or a trustee.

Whatever the disappointments of his career, Waldegrave has been very fortunate in his personal life. Since 1977, he has been very happily married to Caroline, and they have four children. In the last paragraph he writes movingly of his love for his family, who are mentioned at several other points in the memoir.

This is an interesting autobiography by one of the more impressive politicians of the Thatcher-Major years. It prompts the following reflections: that outstanding ability and determination to succeed are not enough, for it is patronage, or the lack of it, that can make or break a career. But even patronage is not enough if the times are out of joint. If Thatcher had made Waldegrave Foreign Secretary in 1989, then he would have been able to contest the leadership in 1990. But if he had, the result unfortunately would have been the same. It is indicative of how fast social change proceeded that, less than thirty years from the time Waldegrave conceived his ambition, perfectly achievable in the hierarchical society that Britain then still was, it had become totally unachievable by 1990. If he had been born fifty years earlier, his background and intellect would have been considered assets (as they should be in any well-ordered society) rather than the liabilities that they became in the dreary, downmarket and democratic world of the late twentieth century. Future historians may well see the importance of this memoir in the fact that Waldegrave is almost certain to be the last aristocrat who aspired to be Prime Minister.

*****

Angela Ellis-Jones is a freelance writer and the author of Conservative Thinkers (1988). She addressed the Traditional Britain Group’s 2013 conference on ‘The Forces Destroying Britain from Within’

Like this:

Like Loading...

A Halloween Horror Story in the House

A Halloween Horror Story in the House

Vaulting Ambition, Thwarted

William Waldegrave in 1981

Vaulting Ambition, Thwarted

ANGELA ELLIS-JONES reviews a timely political memoir

A Different Kind of Weather, WILLIAM WALDEGRAVE, 2015, Constable, ISBN 978-1-4721-1975-9, £20

As an undergraduate at Oxford in the late 1970s, on visits to the Union I enjoyed looking at the photographs on the wall of past Presidents and their committees. One in particular caught my attention: Trinity Term, 1968. The President was a handsome young man, the Hon. William Waldegrave, who was flanked by the Queen (on her one and only visit to the Union) and Sir Harold Macmillan. After Waldegrave had been elected to Parliament as MP for Bristol West in 1979, he came to speak to the University Conservative Association. I assumed that he would become the next Conservative leader but one (he is a generation younger than Thatcher), and then Prime Minister. Never could I have imagined how things would turn out!

And neither could he. Published eighteen years after the author retired from politics (coincidentally the same amount of time he spent as an MP), this book is ‘an attempt to explain how things felt, to describe the weather of a life’. How it felt to have held the ambition to be Prime Minister for so long, then to be bitterly disappointed.

The memoir begins with an evocation of the Christmases of William’s very happy childhood at Chewton House in the village of Chewton Mendip in Somerset, ‘a world we have lost’. He was born in 1946, the youngest of seven children of the twelfth Earl and Countess Waldegrave. His mother, who had won a scholarship to read History at Somerville College, Oxford, had left before graduating, to get married in 1930.The Waldegraves had five daughters, followed by two sons. Much is made by psychologists of birth order as an influence on character. Did being the youngest (by six years) give William a burning determination to make his mark on the world, to be noticed? ‘And what better way than by becoming the most famous person in the world, applauded by all?’ At the age of fifteen, his free-floating ambition crystallised: he decided that he would be Prime Minister.

In the early Sixties, this appeared to be a perfectly realistic ambition. The patricians were still in charge of the Conservative party. The Waldegraves had been part of the ruling class for eight centuries. Walpole was an ancestor. William’s maternal grandmother, Hilda Lyttelton, was related to ‘half the intellectual and governmental elite of Victorian and Edwardian England’. And William himself evidently had a brilliant mind. As a child he read voraciously, excelled at Classics at his Prep School, and entered Eton as an Oppidan Scholar. After an intellectually omnivorous time at Eton, ranging over arts and sciences, a scholarship to Corpus Christi College Oxford followed. He was aware that he was living in a world that was on the cusp of change: ‘I arrived at the end of a culture and a social system that would not have been wholly unrecognisable in 1555, 1655, 1755, let alone 1855….No sooner had I mastered Virgil, Horace, Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides than they disappeared as the central reference points for educated discourse that they had been since the Renaissance’. His attitude to these changes was schizophrenic: ‘On the one hand, I loved the old culture; on the other I celebrated the radicalism of those who set out to destroy it’.

After taking an uncharacteristic Second in Mods, he made up for it with a congratulated First in Greats. He overcame his shyness to become President of the Union. He was also President of the Conservative Association. Waldegrave won most of the glittering prizes at Oxford, although he doesn’t appear to have captained a University Challenge team. After Oxford, he went to Harvard as a Kennedy Scholar to study political philosophy, a subject which was moribund at Oxford at that time, obsessed as it was with dry-as-dust linguistic philosophy. The following year, in 1971, he won a prize fellowship at All Souls’ College, the very acme of academic distinction.

By this time, he had embarked on his first job, in Lord Rothschild’s Central Policy Review Staff or ‘Think Tank’. Although he obtained this employment through his father’s connections in the House of Lords, he certainly deserved it on the basis of his academic record. Association with Rothschild enabled him to meet some of the most interesting people of the time – Nobel Prize winners, heads of Oxbridge colleges, inter al – and he soon became engaged to Rothschild’s daughter, Victoria. For Waldegrave, ‘Rothschild provided a dramatic embodiment of the perpetual search that partly drove my ambition: here was the romance of the mystery at the heart of the state; here were the people who knew the meanings of the nods and the winks which signalled that the world was not what it seemed’. However, having (via the Rothschilds) the likes of the hard–left Barbara Wootton, who exercised a very malign influence on postwar Britain (she should have been included in Quentin Letts’ ‘Fifty People Who Buggered Up Britain’) as ‘my tutor in penal policy’ doesn’t seem to have been an entirely suitable preparation for a Conservative MP!

In autumn 1973 Waldegrave left the civil service to become political secretary to Edward Heath, succeeding Douglas Hurd who had been selected to fight Mid-Oxfordshire (which became Witney in 1983). He remained in post until Margaret Thatcher became Conservative leader in January 1975. Rejecting Henry Keswick’s offer of the political editorship of The Spectator, he went to work for Arnold Weinstock, MD of GEC, then the largest private sector company in Britain. This would ‘allow my princely education to continue: I needed to know about industry and the real world’. In his spare time he wrote The Binding of Leviathan, which was published to great acclaim in 1978. Described on the dust-jacket as ‘an attempt to restate the fundamental moral and intellectual basis of Conservatism’, it predicted the imminent collapse of the Soviet Union. The following year he was elected to Parliament for Bristol West, twelve miles away from Chewton Mendip.

Anyone who is in any doubt as to the relative merits of Thatcher and Heath as people should consider this: whereas Waldegrave’s close association with Heath did not deter Thatcher from appointing him a Minister in 1981 (parliamentary secretary for higher education) upon this appointment, Heath refused to speak to him for several years! Waldegrave remained in office continuously in a variety of Ministries until the accession of the Blair government in 1997. The job he most enjoyed was that of Minister of State at the Foreign Office from 1988 to 1990.This coincided with the world-historical event of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the liberation of Eastern Europe. For his work in this area, Pope John Paul 11 wished to make him a Papal Knight; Waldegrave was furious when the Foreign Office refused the honour without consulting him. But this fascinating job nearly ended in fatality. In September 1990 he was scheduled to address a meeting of senior counter-terrorism experts from Britain and its main allies at the Royal Overseas League: ‘The IRA had hidden a large Semtex bomb in the lectern from which I was to have spoken. It was discovered by accident. If it had gone off, it would certainly have killed me as well as many others in the audience’.

He cannot have been the only politician at this time to have had such a lucky escape. In 1979 and 1990 two Conservative MPs were murdered, and five people lost their lives in the Brighton hotel bomb, designed to assassinate Margaret Thatcher, in 1984. Whatever else one may think of the politicians of this era, they were brave people: death was an omnipresent threat.

Shortly after this, Thatcher appointed Waldegrave to the Cabinet as Secretary of State for Health; he turned out to be her last appointment before her fall. Unlike some others, Waldegrave emerges honourably from an event which he describes as a ‘tragedy’ and a ‘shameful period’: ‘Such a figure should only ever be defeated by the electorate…there was something unfitting, wrong, about a party that owed one person so much, disposing of her in such a callous way’. Although he was initially not much in sympathy with Thatcherism, the proven success of her policies made him rethink some of his earlier views, and he records his pride at having served in her governments.

One can only sympathise with how Waldegrave must have felt when John Major became Prime Minister. For a former President of the Oxford Union, and Fellow of All Souls, the scion of a distinguished family, to have been put in the shade by a nonentity who left school with three O Levels must have been both painful and infuriating. The cruel bouleversement of what many people would consider to be the two men’s rightful positions was doubtless understood by Private Eye when they lampooned Waldegrave as ‘the man who makes the tea’. His comment on the situation is terse: ‘I had become used to Chris Patten beating me in our generation, but John Major?’

Major was only in a position to run for the leadership because of Thatcher’s spectacularly bad judgment of people, a characteristic which has become more plainly apparent since her death, with the revelations about her appointment of the pederast Peter Morrison MP to be Deputy Chairman of the Party and later her PPS, and her insistence on a knighthood for Jimmy Savile, despite strong warnings in both cases. (A more competent man than Morrison as campaign manager would have ensured that Thatcher remained leader in 1990). Thatcher, inexplicably thinking that Major was ‘one of us’, appointed him in quick succession Foreign Secretary, then Chancellor in 1989; clear evidence that her premiership was in its death-throes. She could so easily have appointed the FCO’s highly-regarded Minister of State to the top job; he would then have been in a position to stand for the leadership in1990. Instead, the Foreign Office was lumbered with a man to whom officials had to point out places on maps! And Treasury officials were doubtless shocked to discover that the custodian of the nation’s finances had left school having failed O Level Maths! As Chancellor, Major insisted on joining the ERM; the Treasury estimated the cost to the taxpayer of the ensuing debacle at £3.5 billion.

The 1990 contest was one of the most dispiriting Conservative leadership contests I can remember. Douglas Hurd, by a long way the ablest candidate, was considered unsuitable precisely because he had attended the best school in the country. Major, the epitome of ordinariness, was considered to be the ‘meritocratic’ candidate; one wondered why Hurd’s First from Cambridge and first place in the Foreign Office entrance examination were not considered strong evidence of merit. The fact that Hurd’s father had been a life peer (after a career as a Conservative MP) was also held against him. The son of a hereditary peer would have been persona even more non grata.

From the 1990 leadership contest, it looked as if nobody in the traditional Tory leader mould – upper-class background, top public school, Oxbridge – would ever again have a chance of leading the party. But would Waldegrave have been any more successful as PM than Major?

He certainly wouldn’t have been the international laughing-stock that Major became – perhaps the only good thing about the Major years was that they showed how important a good education is for a Premier. It would have been uplifting for Britain to have a Prime Minister in the tradition of the great scholar-statesmen of the Victorian and Edwardian era: Gladstone, Salisbury, Balfour, Rosebery, Asquith, Haldane, Curzon, and many others. (Waldegrave is even distantly related to Gladstone: his grandmother, Hilda Lyttelton, was the grand-daughter of Mrs Gladstone’s sister, and several of her Lyttelton aunts and uncles were close friends of Balfour.) And Waldegrave would not have presided over the polytechnics becoming ‘universities’, one of Major’s worst policy mistakes. But from the time of the Falklands War, when he saw Thatcher’s ‘capacity to withstand the relentless pressure that never leaves the holder of the highest office’, he ‘had to recognise that I could not have done what she did’.

Not that Major was any tougher. But one of the worst things about Major, together with his obvious inadequacy and unsuitability for the role, was his social liberalism. Waldegrave would have been happy to lead a socially liberal party: ‘In general, I shared the views of Chris Patten, Ian Gilmour, Roy Jenkins and Jo Grimond on how to live’. How to live? John Campbell’s recent biography of Jenkins, the godfather of the permissive society, has confirmed what many suspected: that the well-lunched Welshman helped himself liberally to the baronet’s wife, too. Jaded Whigs, with a hole in their heads where a moral sense should be! Nowhere in these memoirs is there any recognition of the cost, both social and financial, of amoral, nonjudgmental liberalism. The annual bill for family breakdown is estimated at £46 billion. Add many millions more for the cost of drug addiction. Waldegrave’s judgement, usually so sound, is woefully deficient in this area.

From the time he entered Parliament in 1979, Waldegrave was identified with the ‘Wets’, the name Thatcher gave to the Heathite liberal Conservatives. Their slogan was ‘One Nation’ and their hero was the unprincipled adventurer Disraeli. How an outlook first popularised in the 1830s could be useful 150 years later in a vastly changed society was never explained. ‘One Nation’ conservatism was devised for a society in which the Christian ethic was still widespread, and in which noblesse oblige and deference bound the different strata of society in mutual obligation. In a society from which deference had disappeared and in which the lower classes stridently insisted on their rights, fresh thinking was required. But the Wets’ judgment was distorted by upper-class guilt, which even Wets who came from a lower social stratum, like Heath, seemed to share. Middle class people resented the fact that, whereas the working classes had the Labour party to fight their corner, the ‘Conservative’ party under Macmillan and Heath and their cronies refused to champion middle-class interests. They also resented the Wets’ patronising attitude to anyone who disagreed with them.

The ‘depressed and depressing country’ (Waldegrave’s phrase) that Britain was in the 1970s was the world the Wets made (with some help from Harold Wilson). J S Mill referred to the Tory party of his day as the ‘stupid party’. Later, this would be a richly-deserved epithet for a party in which the Wets were in charge. What strikes one above all about the Wets is how wrong they were on just about every issue. Firstly, they were wrong on economics. They rejected the free market in favour of corporatism. In 1973 Lord Rothschild predicted that Britain would be half as rich per capita as France and Germany by 2000. Waldegrave acknowledges that without the intervention of Thatcher, this would indeed have happened. Secondly, they were wrong on Europe. Many Wets didn’t understand the constitutional issues, and those who did sought to deceive the British people into thinking that massive transfers of sovereignty were nothing to worry about at all. Waldegrave saw the constitutional issues far more clearly than many of his Wet friends did: pooled ‘sovereignty was a meaningless slogan’. To his credit, he refused to campaign for a ‘Yes’ vote in the 1975 Referendum. Thirdly, they were wrong on the Euro. Arch-Wets Heseltine and Clarke made complete fools of themselves advocating British entry, a position which no reputable economist could be found to endorse. Fourthly, they were wrong on the trade unions. The Wets couldn’t countenance alienating the unions, which were seen as part of Britain’s corporatist settlement. The Wet Jim Prior, Thatcher’s first employment secretary, introduced very limited legislation to bring the unions within the law in 1980. It required Norman Tebbit to finish the job, thus ushering in decades of peaceful industrial relations. Finally, they were wrong on immigration. The Wets expressed dismay about restricting immigration in response to pressure from voters who, unlike the Wets, were actually affected by competition for jobs and housing.

On all of these issues, except possibly for the last, Waldegrave was on the side of the Thatcherites. Yet he gives the impression that although he inclined to Thatcher with his head – how could he not? – his heart is still with the Wets. Nowhere does he mount a sustained critique of their errors.

One of the most depressing aspects of the Major years was the plummeting of standards in state schools, ably documented by Melanie Phillips in All Must Have Prizes (1996). Things must have been pretty bad for Blair to make ‘Education, Education, Education’ his mantra. The main reason for this situation was comprehensive education, and in particular, mixed ability teaching – two forms of social liberalism that no proper conservative could ever endorse. Yet a leading Wet of the Heath era, Old Etonian Edward Boyle (another candidate for Letts’s ‘Fifty People…’) campaigned for the Conservatives to commit themselves to a policy of replacing grammar and secondary modern schools with comprehensives.

It is surprising that nowhere in this memoir does this very academically-oriented politician tell us where he stood on the issue of grammar schools versus comprehensives. Nor does he make any observation on the parlous quality of the education which the great majority of his constituents’ children had to endure in the 1990s – and what he might have done about it if he had become PM. Indeed, surprisingly for someone who was consumed since his teens with the ambition to be Prime Minister, he doesn’t say much about what he would have done in any policy area if he had become PM. One would have expected a sustained critique of Major’s failings, but Waldegrave is silent. Although he was grateful to Major for keeping him in the Cabinet after he had made disparaging remarks about him when he became PM, surely at a distance of over twenty years he should now feel free to speak his mind? It would also be interesting to know what he thinks about the way Britain has developed over the past half-century – what, in his view, are the gains and the losses?

In a chapter entitled ‘Falling off a Precipice’, Waldegrave describes the trauma of losing Bristol West – which had never been anything other than Conservative, and which he had won in 1979 with over 50% of the vote – in the 1997 Labour landslide. Unlike some ‘retread’ MPs who re-enter the House of Commons at a subsequent General Election, he did not try again; he could see now that he would never achieve his cherished ambition. He was still only fifty, and accepted alternative employment in the City, becoming a Vice-Chairman of a major bank. He has some harsh criticisms of the way many individuals and institutions in the City operated: ‘The new ethos was totally fee driven, ruthlessly selfish, disloyal to employers’. Concurrently with his work in the City, he became Chairman of the Science Museum, and Chairman of the Rhodes Trust, both for nearly a decade. In 2009, he became Provost of Eton College. A life peer, Baron Waldegrave of North Hill, since 1999, he has not, on the evidence of this memoir, been a particularly active member of the upper House. He modestly refrains from mentioning all the outfits of which he has been a director or a trustee.

Whatever the disappointments of his career, Waldegrave has been very fortunate in his personal life. Since 1977, he has been very happily married to Caroline, and they have four children. In the last paragraph he writes movingly of his love for his family, who are mentioned at several other points in the memoir.

This is an interesting autobiography by one of the more impressive politicians of the Thatcher-Major years. It prompts the following reflections: that outstanding ability and determination to succeed are not enough, for it is patronage, or the lack of it, that can make or break a career. But even patronage is not enough if the times are out of joint. If Thatcher had made Waldegrave Foreign Secretary in 1989, then he would have been able to contest the leadership in 1990. But if he had, the result unfortunately would have been the same. It is indicative of how fast social change proceeded that, less than thirty years from the time Waldegrave conceived his ambition, perfectly achievable in the hierarchical society that Britain then still was, it had become totally unachievable by 1990. If he had been born fifty years earlier, his background and intellect would have been considered assets (as they should be in any well-ordered society) rather than the liabilities that they became in the dreary, downmarket and democratic world of the late twentieth century. Future historians may well see the importance of this memoir in the fact that Waldegrave is almost certain to be the last aristocrat who aspired to be Prime Minister.

*****

Angela Ellis-Jones is a freelance writer and the author of Conservative Thinkers (1988). She addressed the Traditional Britain Group’s 2013 conference on ‘The Forces Destroying Britain from Within’

Share this:

Like this: