Whaling, Zwischen, 1856

Endnotes, June 2022

In this edition: Vaughan Williams at the Barbican, Lennox Berkeley in Paris, reviewed by Stuart Millson

Many musical events, festivals and programmes this year are celebrating the 150th anniversary of the birth of the great English symphonist, Ralph Vaughan Williams – or RVW as he was known. The composer was one of the inspirational forces behind the cultural phenomenon known as the English Musical Renaissance: the period from the late-19th to early-20th century, when a distinctive national style of music was evolving in these islands. Elgar and Parry already dominated the musical landscape – their work often compared to the sound-world of Brahms – but with Vaughan Williams, a new course for English music was plotted: a journey along the coast and countryside of England, in which folk-songs were collected; and a scholarly immersion in the history of our church music, which led to such masterpieces as the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis.

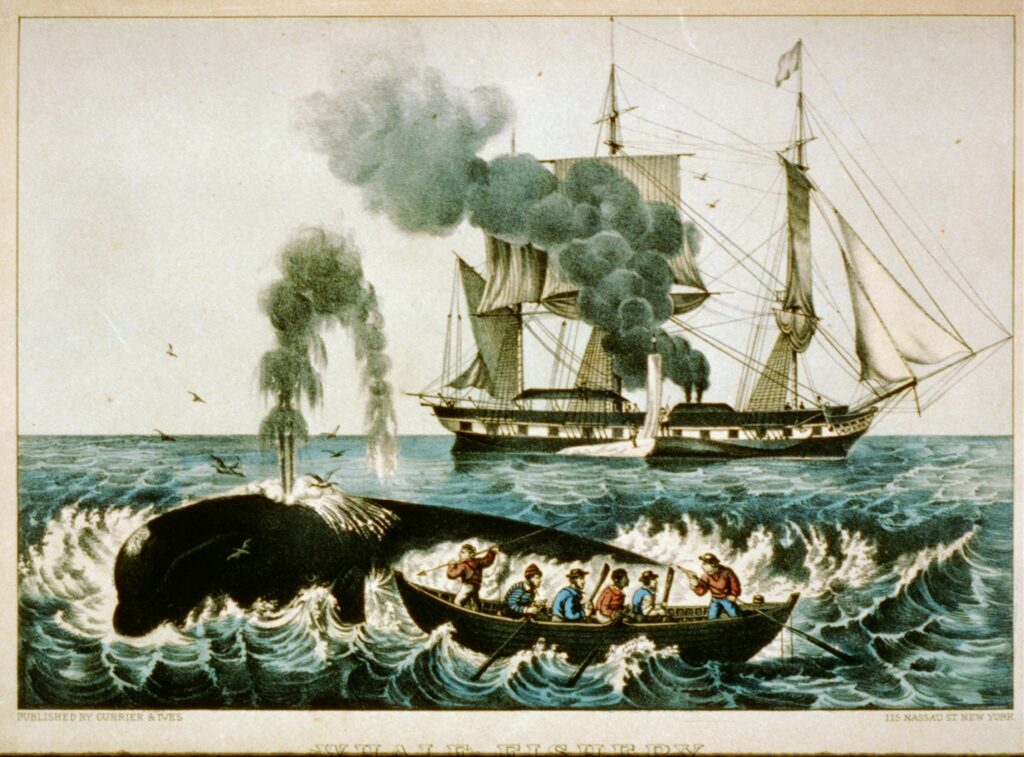

Elements of all sides of Vaughan Williams’s style came together on Tuesday 3rd May at the Barbican Concert Hall, London, as the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and City of London Choir took to the stage, with conductor Hilary Davan Wetton, for a performance of the anniversary composer’s A Sea Symphony. This was his first symphony and completed in 1909 – a substantial work about mankind’s place within the universe which had occupied RVW’s mind for some years. Setting the inspirational words of American 19th-century transcendental poet Walt Whitman, in the first movement the composer depicts a scene in which the ships and “ship-signals of all nations” can be seen: a sunlit moment, beginning with an exhortation, supported by brass, by the full choir – “Behold, the sea itself…”

Yet the piece also works at a much deeper level, and by the second movement, we are beginning to ponder eternity in a slow, processional nocturne: On the Beach at Night Alone. The baritone soloist has an important role to play in this section – and for this performance, the well-known and much-admired Roderick Williams (an advocate of English music) sang the words with an intimate, chamber-like intensity. Although a large hall, somehow the Barbican seems to offer a much “closer” experience for concertgoers; closer to the music and performers: the platform design being such that an orchestra seems to be almost within arm’s reach, or extending into the heart of the front stalls, with ample seating at angles on either extremity of the stage.

Such proximity allowed the Barbican audience that night to savour the soft, silvery string sound of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; the darting detail of woodwind in the shanty-like passages and RVW’s noble writing for horns, which the ensemble’s players clearly relished. Hilary Davan Wetton has been a presence on the conducting podium for many years – and he first came to my attention in a radio broadcast in the early-1990s, in which he conducted Holst’s Marching Song with the Ulster Orchestra – Holst being a friend of Vaughan Williams a fellow folk-enthusiast. More substantial Holst pieces were Davan Wetton specialities on a Hyperion CD with the Philharmonia Orchestra, including a rousing rendition of the old English choral folk-balled, King Estmere. And with many appearances at the English Music Festival to his name, this conductor was certainly right for the great distances, moods and English visionary romanticism of A Sea Symphony.

The maestro inspired some fine singing from the excellent City of London Choir, a formation of choral artists who provided some spine-tingling, hushed moments in the great final movement, The Explorers – and in the work’s extraordinary scherzo movement – The Waves – in which, on the edge of our seat (or deck) we experience tricky, treacherous tides and stormy waves splashing against the sides of our vessel, only for the ship to triumphantly steer through the wind and water. Mention must also be made of the evening’s soprano soloist – Sophie Bevan – whose clear enunciation and strong voice projected above the symphony’s choppy waters and ever-rich, larger-than-life orchestral sound.

Vaughan Williams and Walt Whitman “steer for the deep waters only” in this most majestic of works – the natural successor to Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius and The Kingdom, but more than that: the creation of a choral symphony, recognisably 20th-century in its style and emotions – with wider tonalities, and writing that seems to draw authentic life and energy from the very shores and seascapes of our our island home. Yet the music slowly raises us into a world beyond the physical and real, as if we are seeing through a telescope our own planet and our little lives, “… O vast Rondure, swimming in space” – that beautiful Whitman line. And in the Barbican concert hall, with its razor-edged sound-clarity, the audience emerged exhilarated as if they had been walking along a coastal path – the “ceaseflow flow” of the ocean and the blown spume, just a few precarious footsteps away.

* * *

More English music, this time on a new release from Willowhayne Records, exploring the work of Lennox Berkeley (1903-89) – that delicate, Gallic-like figure – during his fruitful Parisian period. In the inter-war years, Berkeley, who is known primarily as a miniaturist (chamber works, rather than symphonies) studied in Paris with Ravel and Nadia Boulanger, and his music is suffused with the fragrance of that city’s tree-lined boulevards and parks – although there seems to be no actual programme to his music, or a particular representation of a place. Even in the quicker movements, the listener never feels hurried along, or pushed in any particular direction by Berkeley: instead, a gentleness and a lyricism that occasionally puts you in mind of John Ireland – another writer of tender tunes – comes to mind.

The artists engaged for this CD are the young violinist, Emmanuel Bach – a player with many credits to his name already, not least at St. Martin-in-the-Fields and Wigmore Hall; and the highly-experienced South African pianist, soloist and teacher, Jenny Stern – who has performed many great concertos with the major orchestras of her country. They seem to blend perfectly in their well-recorded performances and have a clear feeling for and joy in this 1930s’-era French and French-inspired music.

The longest work by Berkeley on the disc (and his music is framed by pieces by Poulenc and Lili Boulanger) is the Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano from the beginning of the 1930s, but somehow it is the opening item – the thirteen-minute Sonatina for Violin and Piano, written after the Parisian sojourn and dating from the early years of the Second World War, that strikes (at least, for this reviewer) the deepest emotions. Again, it is never heavy-handed or intense, but there is a melancholy feeling within the three movements, all of which have craftsmanship and structure, and lead the listener on a thoughtful journey –a recollection of memories of France, but on a grey afternoon in England.

Stuart Millson is the Classical Music Editor of The Quarterly Review

CD details: Lennox in Paris, Berkeley/Poulenc/Boulanger. Catalogue number: WHR070.

The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library has “confessed” to “racist” material in its archives but will learn from these “wrongs of the past”.

Like the “English Association” and almost everyone else. Gleichschaltung.