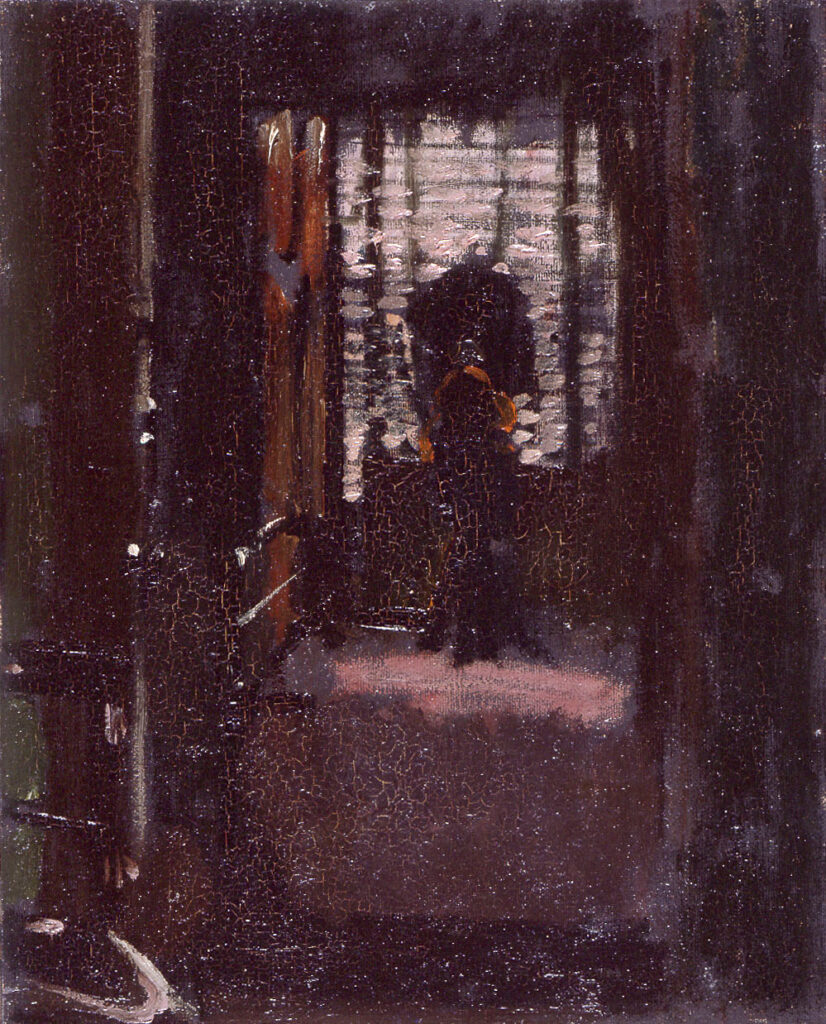

Sickert, Jack the Ripper’s Bedroom

Sick Art

Walter Sickert, Tate Britain, 28 April 2022 – 18 September 2022, an exhibition in collaboration with the Petit Palais, Paris, reviewed by Leslie Jones

Walter Sickert eschewed the “idealised nude”. He painted street vendors, as in Two Coster Girls (1906) but also sex workers, in La Hollandaise (c 1906), Cocotte de Soho (1905), Two Women on a Sofa (1903-1904), Fille Vénetian Allongée (1903-4) and The Prussians in Belgium (1912). In Le Lit de Cuivre (1906), according to one Parisian reviewer, Sickert depicted “whores with withered bodies”. The Star, in 1912, referred disdainfully to an “ordinary street corner loafer”, seated on a bed alongside a half-naked prostitute in Dawn Camden Town (c 1909).

The language changes but the song remains the same. The curators of this exhibition, an Anglo-French collaboration, dissociate themselves from artwork that might ‘objectify women’, likewise from Sickert’s supposedly voyeuristic, ‘keyhole view’, as in Woman Washing her Hair (1906), which brings to mind Degas’ Après le bain femme nue couchée (1885). They draw attention to what they call “the more threatening juxtaposition of male and female figures”, as in the drawing Persuasion (1907). “Some people”, they opine, “are critical of the potential for violence that they see” in works like The Camden Town Murder (c 1907-1908).

Jonathan Jones notes that Sickert called his flat in Camden Town Jack the Ripper’s bedroom (The Guardian, 26 April, Walter Sickert review – serial killer, fantasist or self-hater?). He records that the paper of three letters written by Sickert in 1888 matched that of three of the Ripper’s missives. But it was the crime novelist Patricia Cornwell who first made this contentious claim, in Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed (2002), a somewhat presumptuous title. She evidently failed to convince artist Mark Walter, for one. He considers Cornwell’s book worthless (personal information; and see www.markwalterartist.com)

The inclusion in this exhibition of works by artists that influenced Sickert, at different stages of his career, is effective. His Théatre de Montmartre (1906) was one of a series of his depictions of French theatre and music hall, with distinct echoes of Degas’ The Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le Diable (1906). For a time, Sickert was a pupil and etching assistant in James Abbott McNeil Whistler’s studio. Compare the former’s A Shop in Dieppe (c. 1886) to the latter’s very similar Shop Front: Dieppe (1897-9). Sickert also emulated Whistler’s seascapes. Pierre Bonnard, in turn, was a key influence on his depictions of the female nude, a genre in which he arguably found his métier. Consider, for example, Bonnard’s Femme assoupie sur un lit (1899).

Drinking, gambling, bare knuckle fighting, boredom, concupiscence, exhaustion – all are amply on display herein. Francis Bacon, indicatively, owned Sickert’s Granby Street (1909), which he displayed in his studio. British painting has come a long way from Messrs Millais, Alma-Tadema and Ruskin, although the latter’s painterly evocations of Venetian architecture are superior to those by Whistler (see Chiaroscuro – Ruskin, in darkness and in light, QR, Spring 2012).

Sickert, Ennui, second version

Dr Leslie Jones is the Editor of Quarterly Review

Walter Sickert’s morbidity borders on sadism and resembles Jean Genet, the latter typically idolised by the repulsive “drag” version of “Les Bonnes” at Home theatre, Manchester, 22 November 2018 (quod vide). The Jack the Ripper connection was made by Stephen Knight and especially Patricia Cornwell. The most likely suspect among scores was Aaron Kosminski, but the ritual aspects of the murders are still significant enough to require explanation. Stephen Senise has argued that the murderer wanted to trigger a pogrom in the East End: the curious thing is that a Judeo-Masonic conspiracy was the chief theme of the so-called “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” but the killings preceded by some years the date of this Franco-Russian concoction.