Stalin, 1945, credit Wikipedia

Whitewashing the Great Terror

By Frank Ellis

Guilt and innocence become senseless notions: “guilty” is he who stands in the way of the natural or historical process which has passed judgement over “inferior races”, over individuals “unfit to live” over “dying classes and decadent peoples”. Terror executes these judgements and before its court, all concerned are subjectively innocent:the murdered because they did nothing against the system, and the murderers because they do not really murder but execute a death sentence pronounced by some higher tribunal […] Terror is lawfulness, if law is the law of the movement of some suprahuman force, Nature or History.

Hannah Arendt[1]

-

- Introduction: The Great Terror (Ezhovshchina)

- Stalin’s Reasons for the Great Terror

- Interrogation, Torture and Confessions

- The Role of Terror in the Soviet State

- Stalin Manipulated by the NKVD?

- The Great Terror was not confined to the Red Army

- No Evidence of Large Agent Networks in the Soviet Union Run by Foreign Intelligence Agencies

- Stalin’s Failure to Heed Military Intelligence Data 1940-194

- Further Evidence that Internal Considerations of Power outweighed Concerns about any External Threat

- The Heydrich Dossier and Archives

- The Gang of 13: Stalin names the Core Conspirators

- Faking the Past in order to Control the Present

- The Heart of the Military-Political Conspiracy

- Kliment Efremovich Voroshilov: No Comrade in Arms

- Inconsistent Explanations of Stalin’s Behaviour

- The Party Mind, Ideology and Revolutionary Justice

- Ending the Great Terror and the Meaning of Zagovor (Conspiracy)

- Conclusion

- Introduction: The Great Terror (Ezhovshchina)

Tukhachevsky, credit Wikipedia

In 1937, though the groundwork had been laid well before, Stalin initiated and carried through his sweeping and murderous purge of all Soviet institutions. Old Bolsheviks, among them, Nikolai Bukharin, Martem’ian Riutin, Grigorii Zinoviev, Aleksei Rykov and Iurii Piatakov, along with deputy commissar of defence, Field Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevskii, Field Marshal Vasilii Bliukher, Field Marshal Egorov, Army commanders Iona Iakir, Ieronim Uborevich and August Kork, and Corps commanders Vitovt Putna, Boris Fel’dman and Il’ia Gar’kavyi, were all shot. In the former Soviet Union this mass cull was known as the Ezhovshchina, named after Nikolai Ezhov, the head of the NKVD at the time. In the West, it is also referred to as the Great Terror. The minimum number known to have been executed throughout the Soviet Union is 681,692 but could be as high as 800,000.[2] An execution toll in excess of 1 million is entirely plausible, if deaths arising from deportation and forced-labour are taken into account. Most of the victims died by shooting but in 1990 it was revealed in declassified Soviet documents that in 1937 the Moscow Directorate of the NKVD had pioneered the use of mobile gas killing vans in order to maintain the rate of executions. There are no numbers in the public domain of those gassed by the NKVD and it is not yet known whether the gas-killing technology either in vans or even in dedicated, static gas chambers was used by the NKVD outside of Moscow, in Leningrad, for example, where the execution squads were also struggling to maintain the tempo of executions.

The purge of the Red Army and its institutional aftershocks had grievous consequences in 1941, and thus the question that has exercised historians is why Stalin ran the risk of weakening the defences of the Soviet state by inflicting such damage on the Red Army. The matter was first examined in depth by Robert Conquest in The Great Terror (1968) and then updated in The Great Terror: A Reassessment (1990). The most convincing explanation is that in order to complete the revolution from above and to eradicate all opposition to his rule, Stalin moved to bring all Soviet institutions under his control. By 1939, with all Soviet institutions purged, broken and reconstructed in, and thoroughly imbued with, a Stalinist spirit, the Soviet Union had become the world’s first totalitarian state.

In The Red Army and the Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Soviet Military[3] Peter Whitewood argues that the Conquest analysis of Stalin’s role in the decapitation of the Red Army in the 1930s is not only wrong but cannot be trusted because it was written during the Cold War and is, for that reason, suspect. Writing well after the Cold War, Whitewood, apparently free of the biases and tensions of that time, would have us believe that what he offers is more detached, free of bias and untainted by the ideological struggles of the Cold War and is, therefore, a more reliable account of what happened.

Now, any major revision of the history and origins of the Great Terror, certainly the one proposed by Whitewood, requires a detailed examination of Conquest’s position in order to set out why Whitewood believes Conquest has misinterpreted the evidence. Unfortunately for his case, Whitewood confines his comments on Conquest’s The Great Terror to a few lines in an endnote[4], so providing no clear basis to explain why Conquest apparently got it wrong, and with reference to an edition published in 1973, not the most recent version, noted above, which was published in 1990. The fact that Conquest was writing in the Cold War is irrelevant. Conquest was and remains right to blame Stalin for the violence and fabrications. The fact of the matter is that Stalin ‘was excessively paranoid and obsessed with power’[5] and this did not need to be popularised by Khrushchev. Nor did historians need Khrushchev’s secret speech of 1956, with its partial denunciation of Stalin, to come to any such conclusion, since enough was already known. With Conquest conveniently exiled to the endnotes, Whitewood is then free to pursue his case in defence of Stalin, unimpeded by any fundamental objections from the likes of Conquest or Hannah Arendt, the philosopher-historian, also exiled to the endnotes, along with the Russian historian Nikolai Semenovich Cherushev. Cherushev’s contribution is especially important since his two monographs, Udar po svoim: Krasnaia armiia 1938-1941 (Striking one’s Own: The Red Army 1938-1941, 2003) and 1937 god: Byl li zagovor voennykh? (1937: Was there a Conspiracy of the Military?(2007) provide robust support for the Conquest position. Both monographs are ignored by Whitewood, and for good reason.

2. Stalin’s Reasons for the Great Terror

According to Whitewood, no credible explanation has been offered to explain why Stalin would launch the purge of the military ‘at the same time the regime believed war was approaching’.[6] This is manifestly not the case since Conquest (and others) have done just that. The Conquest position on the Great Terror is that it was a product of Stalin’s paranoia and, above all, his drive to achieve complete power over the Soviet state; that it was the culminating act or one in a series of acts, which, by 1939, led to the world’s first totalitarian state with Stalin firmly ensconced, and all real, potential or imaginary rivals for power vanquished.

Stalin used various instruments and ploys to achieve this goal. While never losing sight of his objective, he, depending on the circumstances of the moment, would adopt a comradely pose or one that was ideologically aggressive or vituperative. A letter of apology sent by Stalin to Tukhachevskii in May 1932 – to clear up a misunderstanding on the latter’s rearmament proposals – and cited by Whitewood to show that Stalin bore Tukhachevskii no grudge, cannot be taken at face value: it was a typical Stalin ploy. Its purpose was to make Stalin appear reasonable and conciliatory so that when, in the future, he turned against Tukhachevskii – and others treated in similar fashion – his reasons for so doing appear more justified and well founded. Tukhachevskii’s diplomatic duties and the fact that he was allowed to travel abroad were merely ruses to strengthen the case against him (accusations of plotting with foreigners, and having betrayed the trust of Comrade Stalin). That certain Red Army commanders had travelled to Germany, Tukhachevskii among them, was also used against them. Public displays of trust in future victims were part of Stalin’s general method, since rewards and displays of trust served to make arrest and execution all the more striking, and were intended to convince domestic and foreign audiences that Stalin must have had very good reasons to move against Tukhachevskii and those alleged to be his fellow plotters in May-June 1937. The 1936 Soviet Constitution, promulgated after the genocide in Ukraine, was another piece of window dressing intended to dupe people, especially Western Sovietophiles, that the worst was over when, in fact, more was about to be inflicted.

Whitewood maintains that the time lag between what could be construed as public demotions and the arrests ‘strongly suggest a level of uncertainty from Stalin about how he should proceed’.[7] Revealed here is not so much Stalin’s uncertainty but Whitewood’s naiveté and lack of understanding of Stalin’s modus operandi. Delays between a public fall from favour and arrest were all part of the psychological processing to which the victim was subjected prior to arrest. The pressure was appalling, and intentional. For example, among Red Army commanders and political commissars who had still not been arrested but who were being slandered there were 782 and 832 recorded cases of suicide and attempted suicide in 1937 and 1938, respectively. These numbers do not include the Navy (Voenno-morskoi flot).[8]

That all kinds of nonsense had been accumulating in Tukhachevskii’s file for years and that this was followed by demotions and arrest indicates, if not ‘a well-thought-out plan’[9], but evidence of some general plan based on opportunities that might arise or could be made to arise to suit Stalin’s purposes. All the evidence of the Great Terror pertaining to the show trials reveals this trait: one moment the victim is promoted or publicly celebrated then he is out of favour then back in favour and finally the axe falls. Responding to claims made by Mikhail Frinovskii, Ezhov’s deputy, and others, that the conspiracy was suddenly discovered, Robert Conquest points out that ‘The pressure against the Army, though little publicized, had, on the contrary, been gradual and cumulative’.[10] In the case of Iakir the cumulative pressure – the standard NKVD pattern – was applied by targeting his immediate subordinates. One of Iakir’s divisional commanders, Dmitrii Shmidt, who had once told Stalin he would cut off his ears, was arrested without Iakir’s being informed. Another Iakir subordinate, divisional commander Iu. Sablin, was arrested and shot. Conquest writes that a female NKVD officer – at great personal risk – went to see Iakir ‘and told him that she had seen the materials against Sablin, and it was quite clear that he was not guilty’.[11] Yet another indirect blow struck against Iakir was the arrest of Gar’kavyi, another one of his corps commanders and a relation by marriage. Iakir and Tukhachevskii could read the runes: they knew what was coming. Stalin did not need ‘additional supporting material’[12] to be provided by his torture machine. Implying that Stalin moved against the Red Army because he really did believe that it was infiltrated by masses of foreign agents is preposterous.

3. Interrogation, Torture and Confessions

Confessions were extracted by torture and Stalin encouraged its use. In a document circulated to district and regional party secretaries (approximately 21st July 1937) Stalin rebuked party officials for objecting to NKVD methods of interrogation (use of torture). Torture was justified, argued Stalin, because ‘obvious enemies of the people’ were exploiting humane methods of interrogation in order to avoid providing the names of conspirators. According to Stalin, Soviet agencies were compelled to use such methods, since ‘It is known that all bourgeois intelligence agencies apply physical pressure in relation to the representatives of the socialist proletariat, and besides applying it in the most shocking forms. So the question arises: why must socialist intelligence agencies be more humane in relation to the inveterate agents of the bourgeoisie, the accursed enemies of the working class and collective farm workers’.[13] Stalin’s instructions on the use of torture highlight his brutal cynicism and mendacity. Torture, he states, is not to be used on a routine basis but only in exceptional circumstances, and those who have violated this rule, ‘scum such as Zakovskii, Litvin, Uspenskii and others’, applying it ‘to honest people who had been mistakenly arrested’, were subjected to ‘condign retribution’.[14] The loophole for Stalin and his torturers is that the conspiracy against Soviet power constitutes ‘exceptional circumstances’, so there is nothing wrong in the routine use of torture. The Zakovskii condemned by Stalin as ‘scum’ is most likely Leonid Zakovskii who was arrested and condemned to execution on 29th August 1938. However, at the very moment he was being denounced by Stalin in July 1937 he was head of the NKVD Directorate of the Leningrad district, indefatigably arresting and torturing suspects on behalf of Comrade Stalin, blissfully unaware that he had been lined up for future liquidation (having served his usefulness).

Severe and protracted beatings were, in any case, the norm not the exception: ‘If the accused won’t sign your written record of the interrogation, just keep beating him until he does sign.’[15] In some cases, specialist interrogators were used, so-called kolol’shchiki (beaters). They operated without supervision and were able to extract testimonies very quickly and then write up convincing interrogation reports: ‘These people [the beaters] knew nothing about the material on the suspect but were sent to Lefortovo. The arrestee was summoned and they set about beating him. The beating went on until the suspect agreed to give a testimony’.[16]

The role played by beatings and other forms of torture in extracting confessions is also repeatedly confirmed in the statements and memoirs of victims and survivors. For example, in a letter to Stalin from his prison cell, dated 6th April 1937, divisional commander Dmitrii Shmidt, withdrew all his confessions extracted under torture: ‘All the accusations are fantasy, all my testimony is a lie, 100%’ and ‘The main thing is that I am not guilty of anything’.[17]

Head of the Chemical Directorate of the Red Army, Iakov Moiseevich Fishman was arrested on 5th June 1937 and tortured. He was accused of being in a Socialist-Revolutionary organisation, having links with Tukhachevskii and Uborevich, disrupting the chemical armaments of the Red Army, and, for good measure, being an agent of two foreign intelligence organisations and passing information to them on the status of the Red Army’s chemical weapons. Fishman was not shot but ended up in a forced-labour camp. During the process of rehabilitation that ensued after Stalin’s death, Fishman provided details of the torture to which he had been subjected:

Over a six-day period I was allowed no sleep at all, brutally beaten and subjected to the most nightmarish insults. Brought to a state of complete exhaustion and in a drugged-like condition, and in legal terms unaware of what I was doing, I signed this “confession” which was absolutely false from start to finish. Later, when I had regained my senses, I immediately rejected these vile concoctions, but once again I was subjected to the most brutal and malevolent treatment. As a result I was once again forced to sign all kinds of false material, slandering myself and others. In reality I had never been a participant in any conspiracy whatsoever, and had never engaged in any kind of wrecking or espionage activity.[18]

Former NKVD officials, now serving in the newly formed KGB, were dismissed and others were arrested for falsifying evidence. Fishman was totally rehabilitated on 5th January 1955. Justice of sorts caught up with other NKVD figures. Interrogated by the Chief Prosecutor’s office after 1953, as part of the investigation into the alleged military conspiracy, A. A. Avseevich, who was known to have been a brutal and sadistic NKVD interrogator, acknowledged that arrestees were subjected to torture, or in his words, to ‘physical methods of coercion’.[19] In April 1937, Avseevich forced corps commanders, Putna and Primakov, to provide false testimony incriminating Tukhachevskii, Iakir and Fel’dman who were then arrested.

Even the dead were able to strike back at their torturers. From December 1933, Corps Commander Albert Ivanovich Lapin was an aide to the commander of the Special Red Banner Far Eastern Army. He was arrested on 17th May 1937. Lapin’s interrogation record shows that he confessed to being in a counter-revolutionary organisation and to having recruited others. Unable to withstand the prison conditions and torture, Lapin committed suicide (by hanging) on 21st September 1937, leaving a brief suicide note: ‘I have had enough of life, I was beaten very badly, therefore I gave false testimony and so I slandered other people. I am guilty of nothing’.[20] That Lapin had earlier signed his interrogation record which concluded with the wording, ‘I have read the record and it is a truthful record of my words’[21], lacks, in any case, conviction, with or without a suicide note, since it says nothing about the accuracy and veracity of the record itself or the methods used to secure it. The interrogatee’s signature is merely intended to provide a veneer of due process.

That the trial of Tukhachevskii and his co-defendants was a sham – and that Stalin knew they were innocent of any charges – is additionally corroborated by the fact that in an article drafted on the 10th June 1937, and submitted to Stalin for his corrections and approval, the day before the trial and promulgation of the verdict, Lev Mekhlis, at the time editor of Pravda, had already condemned the men as guilty, and in the most vicious and dehumanizing language associated with the Great Terror.[22] Top secret Soviet archival material smuggled out by Vasilii Mitrokhin also unequivocally confirms the lead role played by Stalin in the Great Terror. Not only did Stalin personally supervise the whole gruesome charade, but he also read and corrected the transcripts of the show trials so that they were consistent with confessions of imaginary crimes extracted under torture.[23]

4. The Role of Terror in the Soviet State

Stalin achieved control of the terror apparatus, frequently and misleadingly referred to by Whitewood as ‘the political police’, and controlled party appointments. Show trials and endless campaigns to expose “enemies of the people” and “wreckers” and imaginary spy rings based on false accusations, confessions extracted by extraordinary violence and fabricated evidence were the norms before, during and after the Great Terror. Scapegoats for industrial failures had earlier been sought in the Shakhty (1928) and Metro Vickers (1933) trials. Quite apart from the human catastrophe, the genocide in Ukraine, brushed aside by Whitewood as a mere ‘severe famine in Ukraine during 1932-1933’[24], inflicted utter mayhem on food production. The memory of the genocide among the survivors also played straight into the hands of the Germans in 1941. The invaders were able to exploit the hatred of Soviet power. The fact that Stalin carried through this programme of genocide, with obvious implications for state security and resilience, does not suggest that Stalin would be too concerned about having senior Red Army officers executed in order, finally, to consolidate his power. At the start of the war, senior Red Army officers were victims of Stalin’s need of scapegoats for his cowardly incompetence and dithering: General Dmitrii Pavlov and General-majors Vladimir Klimovskikh, Andrei Grigor’ev and Aleksandr Korobkov were shot after a closed trial. In October 1941, with the Germans closing in on Moscow, thirteen other senior commanders were shot in Kuibyshev.

Katyn Massacre, Mass Graves, credit Wikipedia

In the spring of 1940 the same principle of prophylactic-decapitation terror which had been used in the Great Terror was applied to Polish prisoners of war in NKVD camps, resulting in the executions of 21,857 prisoners (known more widely as the Katyn massacre). Invaded by the Red Army in June 1940, the Baltic States were subjected to the full programme of Sovietization under NKVD supervision. After 22nd June 1941, prisoners in NKVD jails that could not be evacuated because of the speed of the German advance were executed in situ. After the war, the methods of the Great Terror were deployed against enemies of Soviet power in the reoccupied and newly occupied states of Eastern Europe. Major show trials along familiar lines were used to bring populations and fraternal communist parties into line. Stalinist methods were copied in Cuba, China, Cambodia and North Korea. In the Soviet Union itself the use of terror was intensified – the so-called Zhdanovshchina – culminating in the campaign against Jewish writers and intellectuals. Its high point was the uncovering of a plot – the so-called Doctors’ Plot – based on claims that Jewish doctors at the behest of the British and Americans were planning to kill the Soviet leadership. The announcement of this plot came, as was the case with the news of Tukhachevskii’s arrest and execution, out of the blue. After Stalin’s death on 5th March 1953 the campaign ceased and those arrested were released. Terror, justified by Soviet law, was an essential weapon of the Soviet state, insisted on by Lenin, and did not end with the Cheka Red Terror in 1918. Whitewood omits, it should be noted, any mention of the Red Terror and is unaware that the NKVD implemented a programme of terror in the Spanish Civil War (Terror Rojo).

5. Stalin Manipulated by the NKVD?

Whitewood’s explanations of Stalin’s behaviour are confusing. We are told that ‘The reason why Stalin lashed out at his military in such an extreme manner in the summer of 1937 remains a mystery’[25], and:

Stalin launched a wave of repression against the Red Army not as another part of a carefully orchestrated consolidation of power. Rather, he did this from a position of weakness and at the last moment. By mid-1937, in what was recognized as a time of looming war, Stalin misperceived a security threat from within his army. He came to incorrectly believe that it had been infiltrated by foreign agents at all levels. Moreover, not only had these spies managed to get inside the Red Army, but so-called evidence by the political police sketched out a conspiracy at the very heart of the high command.[26]

So are the reasons for Stalin’s behaviour a mystery or not? The real mystery is not why Stalin launched the state-wide Great Terror but why he trusted Hitler and ignored the warnings and evidence of Hitler’s hostility. Whitewood accepts – or rather implies that he accepts – that there was no Red Army plot to overthrow Stalin but nevertheless claims that Stalin genuinely came to believe that there was a plot; that the danger was imagined to be very real and so, reluctantly, Stalin acted to save the Soviet state from a Red Army coup, murdering at least 681,692 in the process. In 1937, according to Whitewood – the claim is on the book’s dust cover – ‘Stalin’s views had been poisoned (sic!) by the paranoid accusations of his secret police…’. Later, Whitewood claims that ‘Ezhov bears direct responsibility for fostering Stalin’s concerns’.[27] Casting Stalin as a victim of NKVD fabrications shifts responsibility for the purge of the Red Army to the NKVD, conveniently referred to as the Ezhovshchina (not the Stalinshchina) – as if Ezhov and the NKVD acted independently of Stalin’s control – and shows, to put it very mildly, no insight into how Stalin functioned. If one accepts that Stalin’s views had been poisoned by the NKVD, then perhaps Holocaust-deniers should add analogous claims to their inventory of fabrications and claim that Himmler, Goebbels, Heydrich and Eichmann induced Hitler’s genocidal hatred of Jews. Consider that Stalin allegedly succumbed to unreliable and invented evidence of a Red Army plot in 1937, put together by the NKVD, yet over the period from January 1940 to June 1941 dismissed all reliable warnings of hostile German intent provided by the same NKVD (and others) as provocation.

Whitewood further undermines his cause by citing Walter Duranty – the first of the Western Holodomor-deniers – as a source for the claim that there had been a conspiracy. Stalin himself was the source of the poison and used the NKVD to administer it. Stalin was also able to convey the impression that he believed that various plots had been discovered and once those identified as plotters had been eradicated the instrument of terror could itself be purged. Even if the purging of the Red Army resulted from Stalin’s mind having been somehow poisoned by the NKVD, the fact that one man – Stalin – could proceed in this manner without being called to account confirms that the Soviet state was relentlessly and irreversibly on the way to becoming a totalitarian state before 1937. Thus, even before this process of transformation had been completed Stalin and his terror apparatus were not subject to any judicial oversight or control and were free to act as they pleased. Members of Stalin’s immediate entourage helped things along. Voroshilov was admirably servile. He had, Whitewood instructs us, little choice but to follow ‘Stalin and the NKVD’s lead in the search for dangerous political enemies’.[28] The ideologically-determined assumption that ‘dangerous political enemies’ were dangerous does not mean that they constituted an objective danger to the Soviet state but merely that they were obstacles to Stalin’s ambitions.

For example, in 1932, in a long document, ‘Stalin and the Crisis of the Proletarian Dictatorship’, that became known as the Riutin platform, Martem’ian Riutin, a Moscow party activist, comprehensively attacked Stalin and his policies. Riutin pulled no punches: ‘In order to destroy the dictatorship of the proletariat and to discredit Leninism, not even the boldest and most brilliant provocateur could have concocted anything better than the leadership of Stalin and his clique’, and: ‘They will protect their dominance in the party and country by lies and slander, executions and arrests, guns and machine guns and with all means and instruments at their disposal since they regard them as their patrimony’.[29] At a meeting of the Politburo Stalin demanded the death penalty for Riutin but was thwarted by Sergei Kirov, Sergo Ordzhonikidze and Valerian Kuibyshev. Kirov was assassinated in December 1934, Ordzhonikidze died, officially of a heart complaint, but the evidence points to murder and Kuibyshev was also supposed to have been struck down by a heart attack. Instead of a bullet, Riutin received a ten-year prison sentence. In October 1936, the new NKVD head, Ezhov, reopened the case against him and he was charged with terrorism. Riutin was found guilty and the bullet he evaded in 1932 caught up with him on 10th January 1937, on the eve of the Great Terror. Cui bono?

Portrait of Kirov, credit Wikipedia

6. The Great Terror was not confined to the Red Army

Another severe failing of the Whitewood thesis is that he examines the purge of the Red Army as if it were the sole Soviet institution to be attacked. The entire Whitewood enterprise does, in fact, depend on this approach, since if the Red Army were the sole target of the Great Terror, the claim that Red Army leaders were planning a coup appears more convincing. The Great Terror – one reason Robert Conquest coined the term – swept across the entire Soviet state, eventually engulfing the NKVD. No institution of substance remained untouched which is entirely consistent with Stalin’s striving to create a totalitarian state. Two minor examples in the grand scheme of repression and slaughter can be cited. Various astronomers at the Pul’kovo observatory were purged. Conquest reports that ‘about twenty-seven astronomers, mostly leading figures, disappeared between 1936 and 1938’.[30] In 1937, when the first census conducted after the genocide in Ukraine revealed a huge population deficit, Stalin had some of the census-takers arrested and shot. It was claimed that enemies of the people, Trotskyites and Bukharinites, had sabotaged the census. If, on the other hand, there had been genuine grounds for dealing with a plot in the Red Army, then action to neutralise the plot would have been reasonably confined to the plotters and would not have required waves of terror and executions to be directed at other vital state institutions. The Red Army plotters would have been isolated and liquidated without disrupting the entire state. It can be done, as Hitler’s response to the failed 20th July 1944 bomb plot showed: the plotters – and these were genuine – their allies and suspects were hunted down and executed and at the same time as Hitler was having to contend with the aftermath of the Normandy landings and the ongoing Soviet summer offensive (Operation Bagration).

The scale of the Red Army purge – the executions and arrests – is entirely consistent with Stalin’s ambitions to render the Red Army, as with all other Soviet institutions, completely subservient to his will, even if that meant the elimination of all initiative and independent action, so vital in war. Reading Whitewood’s study one could be forgiven for thinking that a mere handful of senior Red Army officers were purged when in fact large numbers were arrested and executed. It is striking that in a study devoted to the purge of the Red Army Whitewood provides no details of the number of Red Army officers targeted, whereas Conquest provides the numbers available to him in 1990. Those purged – a mere sample it should be noted – were 3 out of the 5 marshals, 13 of the 15 army commanders (86%), 50 of the 57 corps commanders (88%) and 154 of the 186 divisional commanders (83%).[31] At least twenty other generals from the Moscow headquarters were executed and institutions, such as the Kremlin Military School and the Frunze Military Academy were targeted by waves of arrests.[32] Had Stalin’s butchery been confined to Tukhachevskii and a handful of other senior officers the Red Army could have quickly recovered. The real damage was done by the scale of the purge in the ranks of the army, corps and divisional commanders and, in the long term, by the crushing of initiative and independent action. The institutional expertise and experience embodied in those sorts of losses cannot easily be made good, since this was the leadership core of the Red Army. Further damage was inflicted by encouraging junior ranks to denounce superiors as spies and Trotskyites. Such a policy is utterly corrosive of honour, discipline and esprit de corps. In all these measures, made worse by Stalin’s failure to heed reliable intelligence – wrecking on a grand scale – we find the causes of the military disasters of 1941 and 1942, and the inability of the Red Army to match German tactical leadership and skill, despite a narrowing of the gap, by May 1945.

Some idea of the disastrous effects of the purge inflicted on the Red Army is conveyed in the numbers of commanders who were not executed but who were discharged from service, arrested and sent to forced-labour camps.[33] In the Moscow Military District 683 were discharged from the main arms of service, including 98 from the air force. 408 were expelled from the party. By November 1937 it was reported (as at 15th October 1937) that 1,063 military personnel had been discharged. In the Belorussian Military District 500 were discharged, including 180 from the air force. In one division – the 81st Division – the entire command and political staff was replaced. By November 1937, 1,300 had been discharged. Of those discharged 400 army personnel were arrested. In the Leningrad Military District there were 550 discharges from the command staff along with 70 from the political staff. 11 senior figures were arrested in the Central Asian Military District. In the Kharkov Military District 408 personnel were discharged, infantry and artillery units being heavily purged. In the same district the commander, chief of staff, two heads of the political section were arrested as enemies of the people. Along with these arrests it was proposed to discharge 1,644 personnel.

In the North-Caucasus Military District 388 were discharged from the Red Army of whom 89 were political personnel and 38 from the air force. The commissar of this district was replaced and his successor, Corps Commissar K. G. Sidorov, stated, implying that his predecessor had not been ruthless enough, that ‘With every passing day ever more people are exposed as participants of insurgent organisations in Cossack units, and as saboteur-spies as well’.[34] 675 personnel of the command staff had been removed and discharged, 178 from the political staff about 50 of whom had been arrested as enemies of the people. This was, according to Sidorov, just the start and he expected that more enemies of the people would be exposed.

In the Belorussian Military District 105 were expelled and there was an almost 100% replacement of the cadres. Lieutenants found themselves promoted to regimental chiefs of staff, and senior lieutenants were promoted to heads of sections at division. In the Special Red Banner Far Eastern Army there were in excess of 500 discharges a large proportion of whom were supposedly participants in a military-fascist organisation. Many of those exposed were senior figures: corps commanders, divisional commanders, six heads of divisional political departments, three officials from the Army’s political directorate and whole series of political workers from the senior and middle strata. It can also be noted that 180 were expelled from the Military-Political Academy 68 of whom were teachers (34 arrested). All heads of the department dedicated to the study of the social-economic cycle, 7 in all, turned out to be “enemies of the people”. Over the period of June-July 1937 another 32 were discharged 26 of whom were teachers. One of those purged in the Kiev Military District who survived to tell the tale, was A. V. Gorbatov whose memoir, Gody i voiny (Years and Wars) – completely ignored by Whitewood – is an important survivor’s account of the Great Terror.

After Ian Gamarnik’s suicide Petr Aleksandrovich Smirnov was appointed the new head of the Red Army Political Directorate. Despite his best efforts to endorse the Great Terror and paint a glowing picture of success – ‘The policy of the Central Committee is a correct one [pravil’naia]’[35] – Smirnov could not hide consequences other than expulsions and arrests. He noted, for example, that in recent months some 10,000 men had been expelled from the Red Army but there were still enemies of the people everywhere. Indices of collapsing morale and poor leadership were evident in the fact that in the first quarter of 1937, 7,520 incidents of injury were recorded in the Kiev military district of whom 1,690 were hospitalised. Smirnov provided no figures for other military districts but it is reasonable to assume that these levels would have been replicated in other military districts. There was also a breakdown of discipline in the Red Army as a whole. In the first four months of 1937 400,000 disciplinary violations were registered. This disciplinary collapse resulted in accidents, suicides, acts of arson and self-mutilation. Unfortunately for Smirnov all his posturing and ideological virtue-signalling did not save him. On 30th June 1938 he, too, was arrested, accused of being part of some military conspiracy and shot on 23rd February 1939. He was rehabilitated on 16th May 1956.

The crisis was replicated in other military districts. During a session of the Military Council convened on 21st November 1937, N. V. Kuibyshev, the commander of the Transcaucasian Military District, told Voroshilov that the state of the rifle divisions was utterly unsatisfactory and told him why: ‘The main reason why we have been unable to eliminate all these shortcomings arises from the fact that our district suffered a very high level of bloodletting’.[36] To fill the gaps created by the ‘bloodletting’ junior officers have been promoted. The Armenian Division is now being commanded by a captain because, as Kuibyshev told Voroshilov, ‘we could not find anyone better’. Things were just as bad in the Azerbaidzhan and Georgian divisions, the former now commanded by a major who prior to this appointment ‘had commanded neither a regiment nor a battalion. During the last 6 years he had been a teacher in a military academy’.[37] Instead of registering despair at the damage done to the Transcaucasian Military District, a strategically important border region, Kuibyshev’s audience laughed. The Georgian division was also commanded by a major who in the last two years had commanded nothing more than a company and lacked the necessary training for higher level command. Oblivious to the damage being inflicted on the Red Army, Budennyi, a loyal Stalin crony, interjected from the floor that the major could acquire the experience within a year, confirming thereby his lamentable military ignorance and the utterly corrosive effects inflicted on the Red Army by the Great Terror.[38] As a member of the Stavka which was formed on 23rd June 1941, among other appointments, Budennyi was well placed to injure the Soviet cause throughout the Great Fatherland War.

Undeterred by Budennyi’s woeful and aggressive ignorance, Kuibyshev highlighted more damage. Discharges and arrests had resulted in ‘the most massive deficit’ in his military district, amounting to a loss of 1,312 command personnel (25%), rising to a deficit of 40%-50% in specialist units.[39] A further blow to operational efficiency was indicated by the fact that a very large percentage of the command personnel in the divisions lacked a sufficient grasp of Russian and could not read orders or manuals. Indicative here is that Russians comprised the majority of the command personnel who had been discharged and arrested and that their rapidly promoted replacements were natsmeny (national minorities). The consequences for operational effectiveness were disastrous and were not fully remedied by the time the Germans penetrated deep into the Caucasus in the second half of 1942.

The consequences catalogued by Smirnov and Kuibyshev were immediate and obvious, even if publicly denied. Others were not immediately obvious. As a consequence of the Great Terror, the Red Army had been thoroughly inculcated with a fear of initiative and independent thinking and action which cost the Red Army dear against the Finns (1939-1940). In 1941, against a far more formidable enemy whose commanders at all levels were not burdened by the interference of political functionaries (military commissars) in tactical decisions and who were expected to show aggressive initiative, the general incompetence and negligence of the Red Army’s leadership strata proved to be lethal shortcomings.

To put the personnel losses inflicted on the Red Army during the Great Terror into a comparative perspective, it can be noted that of a total minimum number of 681,692 executions known to have been carried out over the period July 1937 to November 1938, 247,157 (36.3%) were executed in the so-called national operations aimed at Poles and Ukrainians, among others.[40] This number of executions – often based on specific quotas – confirms the deadly scope of the Great Terror which went way beyond the Red Army, and served Stalin’s ambitions to totalitarianise the Soviet state.

Once it is acknowledged – the evidence is clear enough – that the Great Terror was state-wide and hit all Soviet institutions, Whitewood’s claim that Stalin moved against the Red Army, singling it out because he had good grounds to believe a coup was imminent, is no longer tenable and collapses. Evidence cited by Robert Conquest shows that the Soviet Navy was hit even harder than the Red Army and that secondary and tertiary terror waves inflicted more damage on the Red Army than the arrest and execution of Tukhachevskii et al in June 1937. It was one thing to liquidate identified plotters at the top of the Red Army in order to prevent a coup but quite different purposes are indicated by launching terror waves against junior and middle command strata as well and other Soviet institutions. Whitewood’s claim that ‘the military purge beginning in early June 1937 was in no sense a culmination of a rising tide of repression’[41] is simply and demonstrably wrong. The arrests and executions started before 1937 and continued into the following year and beyond. Again, this is clear evidence that the Great Terror was not confined to the Red Army, and was never intended to be.

7. No Evidence of Large Agent Networks in the Soviet Union Run by Foreign Intelligence Agencies

Claims made by Whitewood that in 1937 the NKVD and Stalin believed that the Red Army had been infiltrated by enemy agents also unravel when one considers some of the practical problems of running agent networks. Whitewood fails to explain or to examine how the basic recruitment, training, control, coordination and arming of these hordes of enemy agents could have taken place right under the noses of the OGPU and NKVD, and for so long. In the 1930s the Soviet Union was the most closed society in the world. Foreigners of all kinds, even those devoted to the Soviet experiment (especially those devoted to the Soviet experiment) were carefully monitored and their movements restricted. The organization of an armed conspiracy in the 1930s to topple Stalin’s regime would have required very tight coordination and control. Given that Western source handlers and agent recruiters were unable just to enter the Soviet Union to meet with Red Army conspirators the sole method of effective communication needed to coordinate a coup would have been radio, using encrypted Morse code. Regular encrypted Morse code radio traffic being sent from Western intelligence agencies to their agents inside the Soviet Union and traffic generated by agents inside the Soviet Union would not have escaped the notice of the NKVD. As was demonstrated in WWII, the capture of radio operators opens up the possibility of the radio game.

Even if the NKVD was unable to decode the enciphered radio traffic the meta data would indicate unauthorised and covert radio transmissions to and from the Soviet Union. This would have been compelling evidence to support NKVD claims of a conspiracy. Yet there is nothing. There is another problem. How are Western and Japanese intelligence agencies able to supply these clandestine networks with radios and codes in the first place, and where and when have these agents learned Morse code? According to Whitewood, local NKVD agencies were informed ‘that foreign agents inside the Soviet Union had set up networks primed to spark rebellion at the outbreak of war’.[42] How are all these agents able to operate without being detected by the NKVD? Why has the NKVD not seized weapons, documents, radios and codes? If enemy agents were still going undetected in 1936 and 1937 after all the previous purges and endless calls for fanatical vigilance why has the NKVD so obviously failed to uncover them? Is this wrecking on the part of the NKVD? Has it been penetrated by enemy agents? How is it possible that these networks have not been thoroughly disrupted?

In fact, if Stalin was to be believed, the numbers of foreign agents infiltrating the Soviet Union were enormous. This is also clear from the same article, prepared by Lev Mekhlis on 10th June 1937. In the article, it is claimed that since the capitalist states send ‘thousands and tens of thousands of agents and spies to each other’, this must mean, based on Stalin’s Marxist analysis of the threat, that the bourgeois states are dispatching to the Soviet Union ‘twice, three times as many wreckers, spies, saboteurs and assassins as they would be sending into the rear areas of any bourgeois state’.[43] Again, if Stalin is to be believed, hordes of enemy agents are able to infiltrate Soviet borders at will. Yet none of these bourgeois agents ever seems to be apprehended by the OGPU or NKVD. By contrast, over the period from January to early June 1941 the NKVD border troops were successfully intercepting German agents (a minimum of 1,780, possibly as many as 2,080), as they tried to infiltrate across the Soviet border. Some of these encounters led to exchanges of fire and the seizure of radios.[44] Stalin just shrugged his shoulders.

Sensational claims – asserted in a decree of the Supreme Soviet (28th August 1941) – that the Volga Germans, the first Soviet national minority to suffer massive deportation, had been penetrated by thousands and tens of thousands of Nazi agents were used to justify mass deportation in September 1941.[45] The fact that the Soviet regime devoted huge resources to the mass deportation of over 400,000 Volga Germans when German tank columns were advancing on Moscow, when everything was required to stop them, confirms – again – that Stalin would and did act in ways which any rational assessment would show were detrimental to state security. The same behaviour can be observed in NS-Germany. The allocation of huge material, technical and administrative resources to the implementation of the Holocaust weakened the German war effort.

8. Stalin’s Failure to Heed Military Intelligence Data 1940-1941

Whitewood questions whether Stalin would be willing to execute his most talented officers and endanger the security of the Soviet Union if he believed war was approaching.[46] Stalin, Whitewood maintains, realised that Tukhachevskii and Uborevich were talented commanders and that the Red Army ‘would be worse off without them’ and that ‘it made little sense to have them arrested or to put obstacles in their way for no good reason’.[47] As noted, the purge of the Red Army went way beyond Tukhachevskii and Uborevich to affect the entire Red Army. It may have made little sense to have them arrested in 1934 but it was certainly useful to continue to fabricate the case against them so as to be able to strike at an opportune moment (1937). Even allowing for the danger of an approaching war – finally made possible and more likely by Stalin’s Pact with Hitler in 1939 – if Stalin believed that such a conspiracy was likely the most effective time to launch a coup against Soviet power would be when the Soviet Union was at war, coordinating an uprising against Stalin with a war or invasion. Thus, the best time to launch a purge would be before any war so disrupting the conspirators’ plans and those of their foreign allies. While this renders the Soviet Union more vulnerable to an eventual war, its chances of surviving the war are better, assuming evidence of German hostile intent which started to accumulate from early 1940 is heeded.

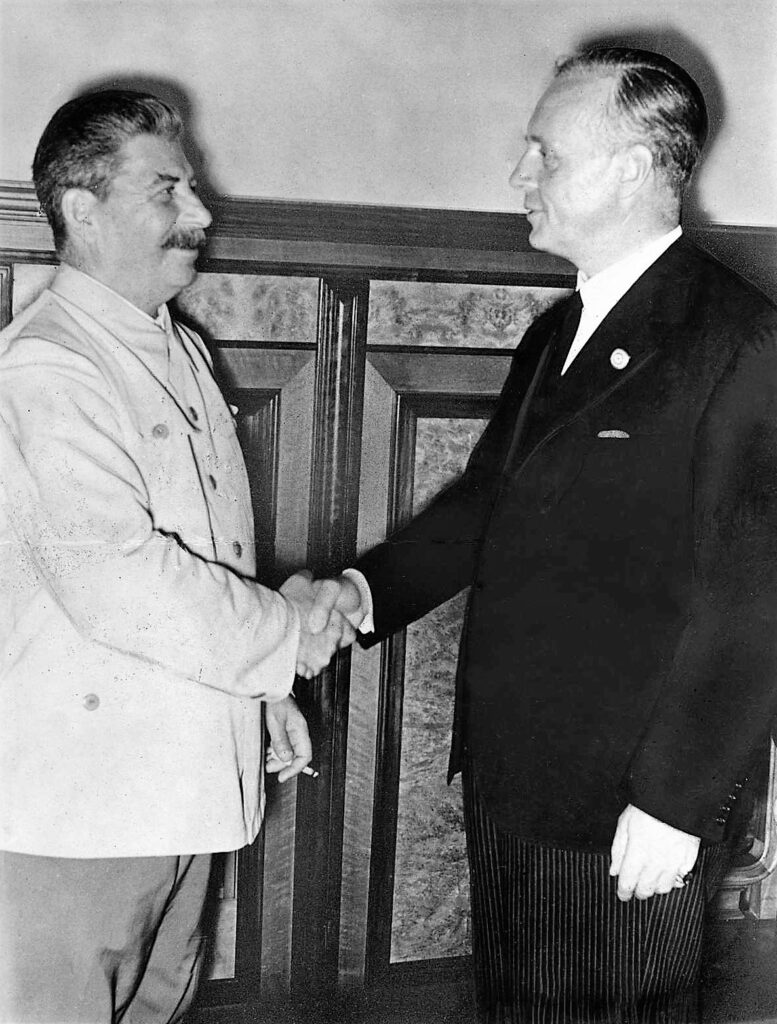

Stalin and Ribbentrop in the Kremlin

Again, it must also be borne in mind that the Great Terror struck not only the Red Army but all the institutions of state power and administration so weakening the state accordingly. Had the purge been confined to the core plotters in the Red Army, the damage would still have been severe, but its debilitating effects were made much worse by its depth and breadth. If, on the other hand, Stalin encouraged the conspiracy to justify purging not just the Red Army in order to complete his final totalitarian revolution, then the massive purge of Soviet society serves both aims: it ensures that Stalin now wields absolute, totalitarian power, but only if the warnings of hostile German intent are heeded and acted on in good time. The elimination of a genuine internal threat, supposedly to be coordinated with external aggression would have led to heightened and intense scrutiny and analysis of all indices of hostile intent by Stalin. The absence of such scrutiny on Stalin’s part suggests that there was no credible internal plot and certainly one not linked to foreign intervention. What made the military disasters of 1941-1942 so nearly fatal for the Soviet regime was the combination of the damage inflicted on the Red Army (and other Soviet institutions) and the failure to heed the obvious and to take the necessary counter measures. The refusal – the failure – to take the German threat seriously was down to one man, Stalin, and so leaves little doubt about his orchestrating role in the state-wide Great Terror in 1937-1938. The fact that Stalin entered into a Non-Aggression Pact with NS-Germany in 1939 and then ignored all the evidence of Germany’s preparations for war makes it clear that Stalin could have had no qualms about attacking the Red Army at a time of a rising risk of war. If Stalin so easily succumbed to wishful thinking over 1940-1941, specifically that he had nothing to fear from Hitler, then he had no grounds to be unduly alarmed by any external threat in 1937-1938.

9. Further Evidence that Internal Considerations of Power outweighed Concerns about any External Threat

That Stalin accorded a higher priority to achieving complete control of, and purging, the Red Army, than border security – the critical consideration in June 1941 – was evident in the purge of the Far Eastern Army in 1937-1938. Here, in the second half of the 1930s, the Japanese threat was real and present. During the extraordinary 4-day session of the Military Council (1st-4th June 1937) Field Marshal Bliukher, commander of the Special Red Banner Far Eastern Army, informed Stalin that there was a serious security problem in the Far East (and he confirmed, in passing, that the Soviet state exploited slave labour):

However, comrade Stalin I must report that if these spies had no large-scale base in other places, then in the Far East they have such a base, and it is apparent from the evidence that this base has been taken into account by the Japanese. In this location there are 340,000 political prisoners working on defence projects, on strategic roads, highways and railway lines. There are about 30,000 rear-echelon militia personnel among whom there is also a certain percentage of political prisoners who are not entirely reliable. And well, the arrestees say that they have already come to an understanding with the Japanese that if they are unable to get their hands on Red Army weapons, then the Japanese will agree to arm 300,000 with their own weapons. This means that the saboteurs have prepared cadres in the Far East numbering 300,000 men, more that is than the male population of the Far East.[48]

Aware of the threat, the Far Eastern Army placed great emphasis on a rapid deployment of Red Army units to meet any Japanese incursion. Rapid deployments were achieved but often at the expense of inadequate clothing and other supplies which led to a physical degradation of the troops and loss of military efficiency. Stalin was aware of these problems – Bliukher told him and all those present – yet despite the evidence of a real threat from the Japanese and obvious shortcomings revealed in deployment, Stalin still went ahead with a purge of the Far Eastern Army regardless of the Japanese threat, a threat that manifested itself in battles at Lake Khasan (1938) and Khalkin-Gol (1939).

Battle of Khalkhin-Gol, credit Wikipedia

Bliukher was arrested on 22nd October 1938. He was accused of espionage and belonging to a military conspiracy. He died of torture in the Lefortovo prison on 9th November 1938. Bliukher, Conquest comments, ‘was a comparatively independent-minded soldier, and (as a candidate member of the Central Committee) a politician, in a position of power and influence’.[49] Men who could think for themselves, who did not automatically defer to Stalin’s supposed genius – Tukhachevskii, Ordzhonikidze, Riutin, Kirov, Iakir and now Bliukher – were prime targets for elimination.

10. The Heydrich Dossier and Archives

An integral part of the story of Stalin’s purge of the Red Army is the dossier containing evidence used by Stalin to incriminate the plotters. It is claimed, variously, that Stalin had the dossier fabricated or that the dossier was assembled by Reinhard Heydrich’s RSHA and delivered to Stalin via a third party in the hope that he would use it to purge his commanders. That this dossier has, so far, not been found in a Russian archive is hardly evidence that it does not exist or has ever existed. The absence of any evidence in Russian archives that Stalin played any part in Kirov’s murder is also not evidence supporting non-complicity on the part of Stalin. Archives contain only what is deposited in them. Certain files pertaining to Tukhachevskii’s file are known to be missing, specifically the record of his first interrogation (25th May 1937) conducted by Zinovii Ushakov, and the record of the face-to-face confrontation with Putna, Primakov and Fel’dman. Precise details of this day – 26th May 1937 – are also not available but something dramatic seems to have happened since Tukhachevskii now acknowledges the existence of an anti-Soviet, military-Trotskyite conspiracy, and that he was in charge of it, implying that hitherto he had denied any conspiracy. Whether this change was beaten out of Tukhachevskii by Ushakov or was due to something else is still not known.[50] Where are these missing interrogation records and what secrets do they hide? Regarding files in general then there is the question of a catalogue indicating what is stored (and where) and any limitations on access to it, and whether, finally, access to stored material is permitted. In the Russian Federation today some files pertaining to the Katyn massacre are still classified. Some archives which were open to researchers in the 1990s have now been closed again or are open but with restricted access.

Whitewood maintains that the lack of any references to the dossier in released archival material and the absence of any reference to it in the transcript of Stalin’s meeting with senior officers before the closed trial (the extraordinary session of the Military Council, 1st-4th June 1937) and the fact that the dossier was not noted, cited or referred to in the actual trial itself, counts against its existence. Since Stalin controlled the record of the meeting, he was in a position to ensure that no mention of the dossier was made. For his part, Conquest concludes that Stalin proceeded cautiously.[51] A dossier that was acquired via a third party, from the German intelligence service, came with the risk that it might contain some deliberate error or flaw which would be very embarrassing were it highlighted. If the source cited by Conquest is accurate then the dossier was used to apply psychological pressure to the judges to convince them that the charges of planning a coup were genuine, and so merited the death penalty. The outrage manifested by officials in the presence of the uninitiated appears all the more powerful and effective for its being based on conviction, reinforced, in this case, by the evidence that Stalin showed them, in confidence, naturally, and never to be mentioned.

Cherushev makes the point that had Tukhachevskii and his fellow plotters been working for German intelligence, and had the documents used to incriminate them been manufactured by the German secret service, German generals would not need to ask about, nor would they have been uncertain of, the provenance of the plot. They would, Cherushev maintains, already have the answers to these questions. [52] One obvious counter is that the fabrication of any dossier and knowledge of its existence – indeed the whole operation – would have been confined to a very small group of people operating on a strictly need-to-know basis. More to the point, why, if Tukhachevskii and colleagues were genuine German agents, would German intelligence wish to sacrifice such valuable assets in 1937, having invested so much time and energy in recruiting them, before their positions at the heart of the Soviet defence establishment had been fully exploited? A dossier assembled with the intention of causing as much disruption as possible would be consistent with the absence of any plot not with its existence.

11. The Gang of 13: Stalin names the Core Conspirators

Leon Trotsky, credit Wikipedia

Stalin named the core military-political conspirators in a speech delivered to the Military Council on 2nd June 1937. They were: Leon Trotskii, Aleksei Rykov, Nikolai Bukharin, Ianis Rudzutak (s), Lev Karakhan, Avel Enukidze, Genrikh Iagoda, Mikhail Tukhachevskii, Iona Iakir, Ieronim Uborevich, August Kork, Eideman and Ian Gamarnik.[53] Whether Stalin intended this conspiracy to be interpreted as some Biblical parody is not clear, but such an interpretation seems unavoidable: Trotskii is cast as the devil, with the other twelve playing the role of treacherous apostles who have betrayed Lenin’s chosen one. According to Stalin the essence of the threat was as follows:

There’s a core consisting of 10 obvious spies and 3 obvious spy recruiters. It is clear that the logic itself of these people depended on the German Reichswehr. If they carry out the instructions of the German Reichswehr, it is clear that the Reichswehr is pushing them in that direction. Here is the heart of the conspiracy. This is a military-political conspiracy, a composition put together by the German Reichswehr. I think that these people are puppets, dolls in the hands of the Reichswehr. The Reichswehr wanted a conspiracy and these gentlemen seized it. The Reichswehr sought to get these gentlemen systematically to provide them with military secrets, and these gentlemen provided the secrets. The Reichswehr sought the removal of the existing government, sought to break it up, but failed. The Reichswehr sought to bring about a situation in which in the event of war everything was ready, in which the army would engage in wrecking; in which the army was not ready for defence. This is what the Reichswehr wanted and it set about preparing the ground. This agent network, the leading core of the military-political conspiracy in the USSR, consists of 10 obvious secret agents and 3 obvious spy recruiters. This is an agent network of the German Reichswehr. That’s the main thing. This conspiracy has, therefore, not so much an internal basis but one based on foreign conditions, not so much to do with the internal policy of our country, but with the policy of the German Reichswehr. They wanted to transform the USSR into a second Spain. To that end, they found and recruited themselves spies and equipped them. That’s the situation.[54]

Although there was no explicit reference to the German dossier in the case against the gang of 13, Stalin’s hammering home the role of the Reichswehr – 12 uses of the word in this passage – may well have been inspired by the dossier’s revelations and adapted by Stalin for his specific purposes. The wording that the conspiracy is ‘a composition put together by the German Reichswehr’ – ‘Eto sobstvennoruchnoe sochinenie germanskogo reikhsvera’ – appears to be either shockingly and inadvertently literal or tantalizingly and deliberately ambiguous. If Heydrich’s file had found its way to Stalin and he knew that file’s contents were false, then referring to the contents of the file as the Reichswehr’s ‘sobstvennoruchnoe sochinenie’ (literally as the ‘written handiwork or written composition’) would be a precise description of Heydrich’s forgery. On the other hand, the wording ‘sobstvennoruchnoe sochinenie’ implies the existence of paperwork or files in Stalin’s possession, which for reasons of security, it is hinted, he cannot show to the delegates, and which proves that the Germans are orchestrating the conspiracy and that Tukhachevskii is guilty.

Three possible interpretations now arise: (i). there is a real conspiracy, initiated and run by the Reichswehr of which Stalin has evidence, though none has so far been provided by him; (ii). the conspiracy is something invented by the Reichswehr in order to destabilize the Soviet regime and Stalin has been fooled; (iii). Stalin is aware that the conspiracy does not exist but the Reichswehr connection provides him with the opportunity to exploit a supposed conspiracy in order to initiate and accelerate the Great Terror. Aware that there is no Reichswehr connection or conspiracy, Stalin makes no references in private or public to the existence of any dossier so as to avoid being embarrassed by German revelations that the dossier was a fake. Public admission of the existence of the dossier and its source would in any case raise very awkward questions about why Stalin was relying on material provided by the same state accused of conducting espionage against the Soviet Union, and which would clearly have a vested interest in causing as much internal conflict as possible. Given the importance played by Tukhachevskii’s connections with Germany in his arrest how would Stalin justify his own connections with the foreign intelligence service of the same state? Is Stalin a German agent, a tool of the Reichswehr?

Even if Stalin recognised the dossier as a fake the fact that he may have exploited it without explicit reference to it or relied on hints to imply its existence still achieves the Reichswehr’s primary goal of weakening the defensive capability of the Soviet state – clear evidence that Stalin is indeed guilty of ‘wrecking’ on a monumental scale – but also satisfies Stalin’s desire to purge the Red Army. Whether Stalin is fooled by the dossier or not but still carries out a mass purge of the Red Army for his own internal purposes, he achieves totalitarian consolidation by 1939. Ultimately, however, Germany, as the future aggressor, is the primary beneficiary of the murderous mayhem inflicted on the Red Army and other Soviet institutions over 1937-1938. Stalin bears full responsibility for this outcome, one whose consequences were nearly made fatal by his failure to take note of critical military intelligence assessments accumulating since 1940.

One final point on the alleged German connection in Stalin’s assault on the Red Army can be noted. On 2nd June 1937, the second day of the extraordinary session of the Military Council, Stalin claimed that Tukhachevskii had ‘passed on our operational plan, the operational plan, the holy of holies to the German Reichswehr’.[55] Four years later in the Kremlin, on 5th May 1941, Stalin addressed a closed session of Red Army officers who had graduated from the various military academies. In a staggering example of understatement he told the graduates that: ‘The Red Army is not the same army it was a few years ago’.[56] Two months later, on 3rd July 1941, when he delivered his radio address, as the Red Army was falling apart and in full retreat, Stalin sought to explain the unfolding disaster to an utterly bewildered population. It strikes me as highly significant that in both cases Stalin omitted any mention of Tukhachevskii and his alleged treachery, specifically the claim that Tukhachevskii had passed on the ‘holy of holies’ to his German masters, in order to account for the success of Germany’s ‘treacherous military attack’ (verolomnoe voennoe napadenie).

12. Faking the Past in order to Control the Present

Record keeping and the manner in which records were maintained, along with the shifting ideological priorities of the Stalin regime, played a huge role in all the purges and trials. Once a file is opened and information collected on an individual in the 1920s (Tukhachevskii, for example) members of the terror apparatus who become involved in the Tukhachevskii case in the 1930s have no way of knowing whether information added in the 1920s is reliable. From the historian’s point of view the Tukhachevskii file is interesting not for any reliable information about alleged plots but for the way in which these plots were fabricated, acquiring a life of their own on which state policy is based: file contents mutated under the intense ideological selection pressures of Stalinist evolution.

Another problem arises from the rumours of treachery and betrayal in the Red Army that were spread by the Soviet intelligence agencies in the 1920s and which were used as bait to ensnare White agents. These rumours also served the very convenient purpose of being used as evidence against Tukhachevskii et al in 1937. If individuals in the NKVD in 1937 were not privy to the deliberate rumours spread by their colleagues in the 1920s about Soviet commanders they would have no grounds to question the veracity of the files and would act accordingly. The result is deception and self-deception on a large scale. In such a way the files are designed to tell the NKVD and Stalin what they wanted to hear and to convince the party that Stalin was vigilant.

That ‘Reprimands were removed from the files of several officers who would be executed just a year later’[57] is meaningless. Were these written reprimands removed and retained in some other facility – spetskhran – so drastically reducing access or were they destroyed? Were the subjects of the files informed? Without answers to these questions there exists no basis for Whitewood to claim that ‘A mass purge was not being prepared’.[58] Again, he fails to grasp the way Stalin behaved, and such claims are obviously inconsistent with earlier acknowledgements that ‘nothing was ever forgotten in the Stalinist system’[59] and that ‘Past black marks were never forgotten…’[60] In the Stalinist system that meant that black marks stored in the memories of Stalin and his executioners were fully admissible as evidence (and they determined what constituted a black mark). The other point to note is that Soviet judges were not independent. The members of the court that judged Tukhachevskii and other senior figures were selected by Stalin. The legal reforms introduced by Alexander II in 1864, among which was a major role for juries, were swept away in 1917. Soviet judges and the NKVD, inspired and guided by their sense of revolutionary justice, now worked towards Stalin, the vozhd’ whose hints, moods, utterances and rages determined the victims and the way they were to be treated. Bureaucrats and administrators overseeing the Holocaust would later behave in the same way: they “worked towards the Führer”.

13. The Heart of the Military-Political Conspiracy

Whitewood’s claim that the repression that would erupt in 1937 arose from NKVD surveillance of the Red Army’s middle ranks in 1936 ‘rather than any concerns about the reliability of the higher command’[61] runs into a number of problems. During the Great Terror, Ezhov’s predecessor, Iagoda, was accused of having deliberately focused attention on the lower ranks of the various conspiratorial groups so as to divert attention from the leaders, Bukharin and Zinoviev.[62] On the other hand, NKVD interest in the middle ranks in 1936 helped to prepare the way to arrest, in due course, the higher commanders, the primary targets. Claims of Trotskyite plots among the middle ranks would make it possible to claim that these middle ranking conspirators were being controlled and led by much senior figures in the Red Army. Uncovering plotters among the middle ranks and extracting confessions under torture thus prepared the way to move against Tukhachevskii et al a year later: start at the bottom and middle and work up. Even if Stalin was not minded to have Tukhachevskii put to death, he could claim that Tukhachevskii’s failure to be aware of what was being fomented in the middle ranks of the Red Army was evidence of negligence and grounds for dismissal.

In view of the fact that Whitewood’s study depends on the claim that the Red Army and party members had been infiltrated by foreign agents his acknowledgement that ‘it is impossible to know for certain’[63] whether Stalin believed the threat was real or was merely a device to blacken political enemies undermines his project. In these circumstances, no reliability can be attributed to the assertion that ‘there is evidence that the perceived threat from foreign agents became a priority for Stalin in the first six months of 1937 and that he came to believe the Soviet Union’s security was in danger’.[64]

The lack of specific detail about what exactly Tukhachevskii and the other military leaders were supposed to have done was obvious to K. E. Polishchuk, head of the Red Army’s Military Electrical-Engineering Academy. Along with others, he attended the four-day session of the Military Council in early June 1937. On the first day of the session the participants were familiarised with the testimonies of the arrested Red Army commanders, Tukhachevskii, Iakir, Uborevich, Kork and others. Here is an extract from Polishchuk’s account:

I was able to read the testimonies of Tukhachevskii and Fel’dman and some of Uborevich’s. I didn’t read any of the testimony of Kork or Iakir, and by all accounts I didn’t miss much. All the testimonies were written according to one and the same format. The format was more or less as follows: what was the aim of the criminal conspiracy of which you were a member; who and in what circumstances recruited you into this criminal conspiracy; what criminal tasks did you carry out; from whom and how much money did you receive for your espionage information passed on to foreign intelligence; and whom did you recruit into the military conspiracy and in what circumstances.

The answers to these questions were stereotypical, fundamentally generalisations, lacking specific details or nuances, associated with the various differences in the professional situation of the accused and his biography. As a rule, concrete facts, precise dates, quantitative and outcome data of the crimes were not indicated, but testimonies were richly endowed with the standard phrases of self-exposure, such as “I embarked on a course of criminal, counter-revolutionary behaviour and treachery of the Motherland with the aim of re-establishing capitalism in the country, the abolition of Soviet power, the physical destruction of the members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and Stalin, the leader of the nations of the world”.[65]

What Polishchuk had been reading – and which was consistent with the testimony of other arrestees it can be noted – was not evidence of some military conspiracy directed at Stalin but a powerful set of clues that the documents prepared by the NKVD and submitted to the Military Council as evidence of Tukhachevskii’s treachery were nothing of the sort. On the contrary, these documents were evidence of fabricated crimes. One will never know how many other participants in early June 1937 came to much the same conclusion as Polishchuk, and fearful of conferring with one another, remained silent, waiting and hoping for the nightmare to end.

There is no evidence that Stalin perceived a genuine threat, or indeed that the threat was objectively genuine, whereas there was a mass of evidence to show that Stalin knew that any threat had been fabricated: he was in permanent contact with Ezhov and took a close interest in the fate of the interrogatees. In any case, evidence that a threat is perceived is quite different from evidence of a threat constructed to serve Stalin’s malevolent purposes. If Stalin perceived the world in such a way that he saw threats of a Red Army coup in 1937 where none reliably and verifiably existed, yet failed to perceive the deadly and very real threat posed by Germany from early 1940, where the evidence was obvious, reliable, demonstrable, relentlessly accumulating, verifiable and emanating from multiple sources, then evidence derived from Stalin’s perceptions of the world is not always reliable.

14. Kliment Efremovich Voroshilov: No Comrade in Arms

Stalin and Voroshilov in the Kremlin, credit Wikipedia

Voroshilov, commissar of defence, played a key role in the purge, slavishly following Stalin, yet Whitewood’s analysis of Voroshilov’s position is erratic and inconsistent. According to Whitewood, Voroshilov apparently had doubts about the reliability of evidence used in the Shakhty trial. Further, he, Voroshilov, ‘was well aware that the political police could build cases on groundless accusations’.[66] Nevertheless, Voroshilov was ‘acutely affected by the military-fascist plot’.[67] Nor, Whitewood asserts, can one dismiss the possibility ‘that even one of Stalin’s closest allies had doubts about the level of truth behind the conspiracy theories that underpinned the violence of the Great Terror’.[68] So, if Voroshilov harboured doubts about ‘the level of truth’ supporting claims of some ‘military-fascist plot’ – at what level was there any truth in these preposterous claims? – what exactly was the cause of his being ‘acutely affected’? Whitewood’s assertion that even if Voroshilov had any doubts about the truth of conspiracies he ‘had no choice but to fall into line’[69] is the essence of the problem. Why did so many senior military figures, men, unlike Voroshilov, with records of conspicuous bravery and competence in action, fail so miserably to stand up to Stalin when men they had served with and whom they knew to be men loyal to the Soviet cause were arrested and publicly vilified? Any alleged reluctance on Voroshilov’s part concerning the purge is not indicated by the fact that in the latter half of 1937 ‘Voroshilov also kept up the pressure in driving the military purge onward’,[70] claiming that the bourgeois states were sending ‘hundreds and thousands of spies to us’.[71] This is also the same Voroshilov who put his signature to Beria’s memorandum (5th March 1940) in which Beria recommended the execution of all Polish prisoners of war held in NKVD camps.

What Voroshilov really thought about the waves of arrests, confessions and NKVD methods is revealed in the advice he gave to Army Commander, Ivan F. Fed’ko, his Assistant Commissar of Defence. Implicated in the confessions of other arrested Red Army commanders, Fed’ko wanted to appeal directly and personally to Ezhov in the hope of proving his innocence. To that end, he asked Voroshilov to arrange a meeting. In 1961, Voroshilov’s former adjutant, reported that Voroshilov tried to dissuade Fed’ko from approaching Ezhov: “You mustn’t go and see Ezhov…there, you’ll be forced to write all kinds of rubbish about yourself…I ask you, don’t do this”. Determined to asset his innocence, Fed’ko went ahead, having assured Voroshilov that he would not sign anything, but with a final warning from Voroshilov: “You’ve a poor grasp of the situation. There, everyone confesses. You mustn’t go there, I ask you”.[72] Fed’ko was later arrested and confessed to being a German spy when confronted with Voroshilov in Lefortovo. He was shot on 26th February 1939.

That Voroshilov happily “worked towards the vozhd’ ” questions the reliability of his report (10th May 1937) submitted to Molotov and Stalin on the scale of the penetration of the Red Army by foreign agents. From the sparse extracts cited by Whitewood – why was this report not provided in full in an appendix, given the importance attached to it by Whitewood? – it is clear enough that Voroshilov is telling Stalin want he wanted to hear. For his part, Molotov continued to maintain well after Stalin’s death that the purge was necessary. This is the same Molotov who denied that there were any secret protocols annexed to the Non-Aggression Pact, protocols which he himself had signed, and the same Molotov who denied any Soviet responsibility for Katyn, having signed the same Beria memorandum along with Stalin, Voroshilov and Mikoian, approving the executions. Perhaps the infamous Beria memorandum is yet another example of the NKVD’s poisoning Stalin’s mind and those of his closest aides.

Cherushev adduces further evidence that Voroshilov willingly colluded with Stalin’s faked conspiracy. For example, he reports that Voroshilov told admiral Kuznetsov that he, Voroshilov, did not believe that Ivan Kuz’mich Kozhanov, the commander of the Black Sea Fleet, was an ‘an enemy of the people’.[73] Cherushev concludes that: ‘These doubts expressed by the “superior beings”, members of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the VKP (b), offer the most important evidence that “the conspiracy of the military” in 1937 was a fabrication’.[74] Cherushev also points out that Voroshilov doubted that Fishman (see above) had ever been guilty of anything, concluding: ‘These doubts and lack of trust demonstrate once more that in 1937 no conspiracy of the military existed’.[75] Voroshilov also interceded on behalf of Corps commissar I. P. Petukhov, stating that he never believed Petukhov was guilty of the crimes imputed to him. After Stalin’s death, Voroshilov, having been petitioned by the widow of Boris Sergeevich Gorbachev (arrested on 3rd May 1937 and shot in June 1937), expressed the view, indirectly, that Gorbachev had done nothing wrong and ordered the chief prosecutor of the USSR to re-examine the case.[76]

15. Inconsistent Explanations of Stalin’s Behaviour

Having acknowledged that ‘The military-fascist plot had no basis in reality’[77], Whitewood then makes a series of bizarre claims: ‘There is much to suggest that Stalin truly believed that this action [purging of the Red Army] was unavoidable based on the evidence he received during the first half of 1937 about an apparent spy infiltration of the Red Army’[78]; ‘Moreover, there is nothing to suggest that this spy scare in the military was cynically contrived’[79]; ‘Stalin was compelled to take action against the Red Army in response to what he believed to be a pressing danger from foreign agents’[80]; and ‘Stalin acted from a position of weakness and perhaps even panic. This is not to say that there were no genuine foreign agents in the Red Army at this time…’.[81] The problem is that Whitewood is unable to name any of these ‘genuine foreign agents’. Who are they? What happened to them? Who controlled them? An extract from the diary of Georgii Dimitrov, the head of the COMINTERN, dated 11th November 1937, in which Stalin is recorded as having stated there was a plot – cited by Whitewood to strengthen his case – is of very little value. Stalin told Dimitrov in the knowledge he would spread the word throughout the COMINTERN that he, Dimitrov, had it from the Comrade Stalin no less that the plot was real (and any person who expressed doubts was obviously a counter-revolutionary or Trotskyite).