The Grave of Wilhelm Fliess, Cemetery Dahlem, Berlin

White Lines

Freud, the Making of an Illusion, Frederick Crews, Henry Holt and Co., New York, 2017, pp 746, HB, US 40$, reviewed by LESLIE JONES

Frederick Crews is Professor Emeritus of English at the University of California. Once an acolyte, he now competes with Jeffrey Masson and Michel Onfray for the coveted title “King of the Freud debunkers” (see “Sigmund Freud, from myth to counter myth”, QR, Autumn 2010).

In Freud, the Making of an Illusion, extensive use is made of the Brautbriefe, the engagement letters of Freud and Martha Bernays, written between 1882 and 1886. Hitherto, some of these letters were unavailable or only available in redacted form. Three of the five planned volumes of this revealing and unexpurgated correspondence have already appeared. Crews contends that they will revolutionize Freud scholarship. The attempts by Freud’s disciples and relatives (especially his daughter Anna) to censor the compromising material therein, including alleged breaches of medical ethics, is a major theme of this book.

The eldest child of Jacob and Amalie Freud, Sigmund was born in Freiberg, Moravia, in 1856. It was here that his father’s wholesale wool business went belly up. He never worked again. In 1860, the family re-located to a Leopoldstadt, a poor, predominantly Jewish quarter of Vienna. Crews maintains that this background of economic insecurity and poverty imbued Sigmund with an insatiable ambition for material success and social advancement. He had five younger sisters and a younger brother (another boy Julius died in early childhood). The family’s hopes rested on the “goldener Sigi”. His uncle Josef’s imprisonment for forging rubles, in 1865, doubtless reinforced his sense of being an outsider. Referring to Freud’s stellar, subsequent career as anatomist, paediatric-neurologist, research scientist, family doctor and scientific author, Crews remarks, “None of those achievements and honours… would slake his appetite for greatness or earn him more than temporary peace of mind” (page 12).

Sigmund was evidently ashamed of his parents, especially of his “uncouth” mother (page 40). Both were Ostjuden, who had emigrated from Galicia. Like Marx, Freud exhibited “one strain of anti-Semitism”, then, contempt for “eastern” Jews. The author provides numerous examples.

Why did Freud opt for a career in medicine? Like Darwin, he hated the sight of blood and “Malfunctioning bodies revolted and depressed him…” (page 31). His earliest intellectual interests were “literary, historical, and philosophical” (page 27). Concerning the latter, in his first year at the University, he mainly studied philosophy, his “real intellectual passion” (page 28). An admirer in his teens of Ludwig Feuerbach, he even considered doing a joint Ph.D. in philosophy and zoology.

At Vienna University, Freud’s mentor and role model was Ernst Brücke. Research science seemed the least-worst option and from 1876 to 1882, he worked as a largely unpaid assistant in Brücke’s Physiological Institute. His transfer in 1882 to Vienna’s General Hospital as a rotating resident was enforced. In order to marry Martha Bernays, to whom he became secretly engaged in that year, he needed a congenial and lucrative speciality to practice (in the event, neurology). According to Crews, Martha’s main attraction was her name. Her grandfather had been the chief rabbi of Hamburg and two of her uncles were distinguished scholars. Although they had fallen on harder times, the Bernayses were decidedly above Freud’s parents’ social station.

The Brautbriefe, replete with patriarchal tropes, provides a unique insight into the four and a half years of Freud’s engagement to Martha, who had moved back to Wandsbek to be with her mother. For much of this period, Freud exhibited an array of psychosomatic and nervous symptoms. In 1875, he had a nervous breakdown and suffered from depression, jealousy and anxiety. Enter cocaine.

Professor Crews calls Freud “the cheerleader for a dangerous drug” (page 73). He thinks that Freud’s involvement with cocaine, viewed objectively, should have done irreparable damage to his reputation. Five detailed chapters, no less, are devoted to this episode. Freud is depicted therein as a man obsessed with “becoming wealthy and making a scientific name” by capitalising on an innovation in medicine. Freud confided to Martha in 1884, “I intend to exploit science instead of allowing myself to be exploited by it”. In the Autumn of 1883, he developed an improved method of staining specimens to be viewed under glass, using gold chloride. In the following year (on April 21, 1884) he told Martha that he intended to “try it [cocaine] out on cases of heart disease, then on nervous exhaustion, particularly in the miserable condition after morphine withdrawal”.

Was Freud’s judgement concerning the risks of cocaine warped by his use of it? This dated from the mid 1880’s to the late 1890’s. He took it to relieve depression, headaches and fatigue and to boost his libido. He even took it before taking the viva to the Privatdozent lectureship.

In 1880, in the Therapeutic Gazette, published in Detroit, Dr W H Bentley claimed to have curbed morphine and alcohol addiction by prescribing cocaine. The Therapeutic Gazette, it transpires, was a house organ of Parke, Davis & Co, a pharmaceutical firm that manufactured cocaine! For Freud, the drug was a “magical remedy” for depression and heart problems that would enable the engaged couple to “possess one another soon”.

On July 1st 1884, Freud’s paper “On Coca” was published in the Centralblatt für Gesamte Therapie. Its conclusion was that cocaine is non-addictive. This was untrue as Freud’s close friend, Professor Ernst Fleischl von Marxow, one of Brücke’s assistants in the Physiological Institute, discovered to his cost, like several other members of the medical profession who injected the “magical remedy”.

Following an accident during an autopsy, Fleischl had become dependant on morphine to relieve pain. Freud’s attempt to wean him off it with cocaine had disastrous results. As Crews observes, “The net effect of Freud’s counsel…had been to turn Fleischl into a double addict” (page 87). Yet Freud refused to retract the assertion in “On Coca” that there is “…an antagonistic relationship between the effect of cocaine and that of morphine” (page 87). Indeed, he continued to recommend cocaine to treat morphine addicts. A brand made by Parke, Davis & Co was probably endorsed by Freud under an assumed name, and that of its rival Merck rubbished, in the Wiener Medizinische Presse, August 9, 1885. Freud received 50-70 florins from Parke, Davis and Co. for his pains. (The article contained an insert that was attributed to Freud).

Hindsight is a fine thing. The author acknowledges that Freud admired and cared deeply for Fleischl. Would he have knowingly risked his friend’s health, not to mention his own and that of his fiancé, to whom he also supplied cocaine? Moreover, its dangers only gradually became apparent. In an article, published in 1885, Albrecht Erlenmeyer, the director of a clinic near Koblenz which specialised in breaking addictions, called cocaine “the third scourge of mankind”. Freud’s lame response to these valid criticisms was that only weak-willed morphinists become addicted to it.

From October 1885 to February 1886, Freud was attached to the Salpêtrière and to its senior physician, the world famous neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. According to Ernest Jones’ biography of Freud, it was Charcot who “…aroused Freud’s interest in hysteria, then in psychopathology in general…” In Austro-German psychiatry, positivism at this juncture was the dominant paradigm. The psychoses were linked to brain pathology. Mental events were perceived as “brain events” and motives and emotions were discounted. In Viennese medical circles, Charcot’s interest in hysteria and his notion of “ideas as a factor in its causation” (page 160), not to mention his use of hypnotism to elicit hysteria, was generally anathema. Although Charcot believed that degeneration was the ultimate cause of the névroses, he contended that “hysteria is, in an absolute manner, a psychical malady” (Charcot, quoted Crews, page 171). A radical break with the positivist perspective was the sine qua non of the development of psychoanalysis, as the premise of the latter is “a mental mechanism of symptom causation…” (page 169), an idea that Freud carried over from Charcot.

Put crudely, Crews’ thesis is that psychoanalysis is pseudo-science. Charcot’s conception of hysteria was pivotal to its development yet the phenomenology of hysteria, as displayed at the Salpêtrière, were entirely attributable, in his view, to “coaching and imitation”. Hysteria is nothing more than “learned behaviour”, induced by suggestion.

But Crews concedes that by taking cocaine, Freud was able to overcome his “prudery, moralism, and deference to authority” (page 73), the sine qua non of of psychoanalysis. In the final chapter of Studies on Hysteria (1895), accordingly, Freud expounded his own theory of the sexual aetiology of the neuroses. A mature nervous system, he averred, is maintained in equilibrium by heterosexual intercourse. Anything which damns up the libido, whether abstinence, impotence, coitus interruptus or premature ejaculation, leads to anxiety neurosis (also termed current neurosis). The psychoneuroses, in contrast, are ideogenic. Unacceptable sexual ideas are repressed and converted into bodily symptoms, or into obsessions and compulsions.

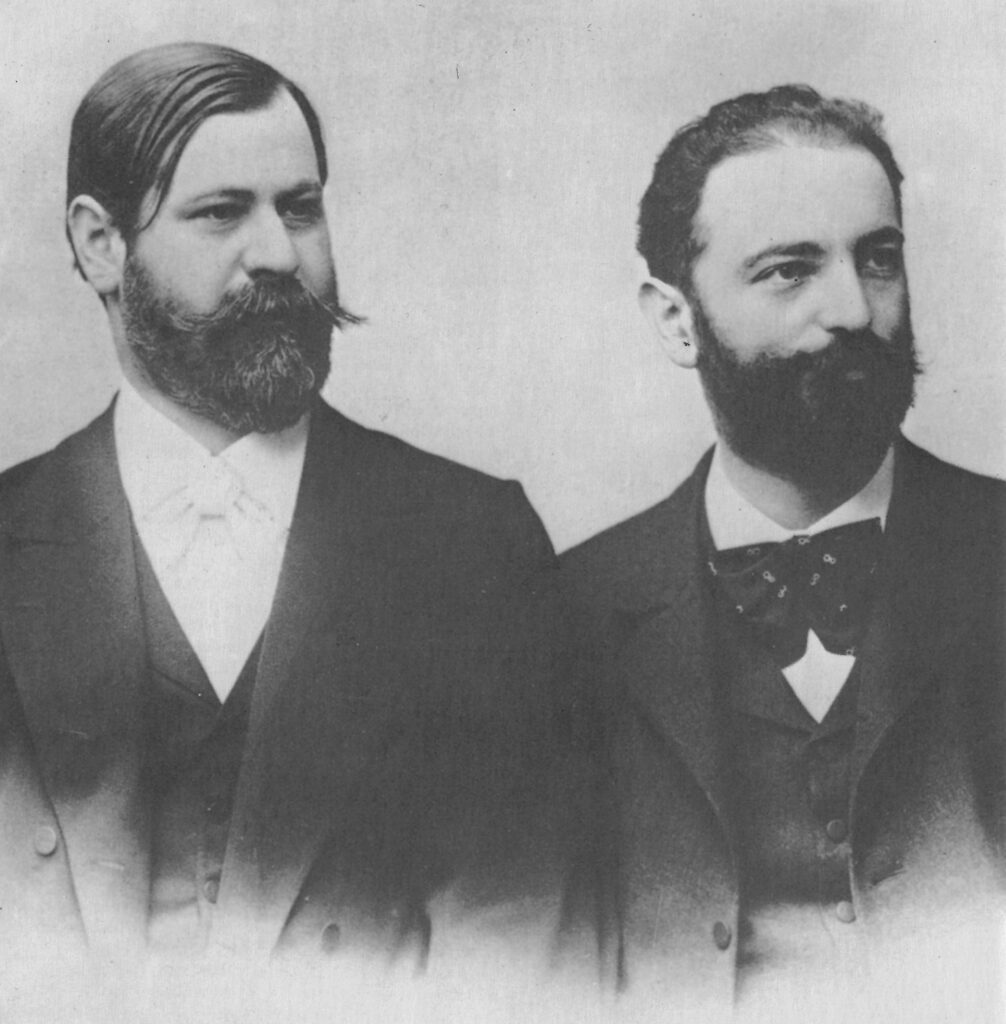

The Berlin internist Wilhelm Fliess, as Crews points out, was the most important person in Freud’s life between 1892 and the turn of the century, “both intellectually and emotionally” (page 415). As such, it is difficult to over state his influence on the development of psychoanalysis. Among the key concepts for which Freud was indebted to Fliess were bisexuality, the latency period and sublimation.

The author emphasises the threat that Freud’s letters to Fliess eventually posed to his reputation. First, they show that Freud was “in most respects the subordinate and more credulous party” (page 416). He was incapable, it seems, of objectively assessing his close friend’s scientific ideas, notably the “nasal reflex neurosis” (although Fliess did not invent this theory). Fliess, in contrast, was self-confident enough to perform this task for Freud. The other threat posed by this candid correspondence was that it suggests a distinctly sexual dimension to the relationship. Freud confided in 1898, “Eleven years ago I already realized that it was necessary for me to love you in order to enrich my life” (page 422). Crews claims that Freud’s libido was “redistributed” from his wife Martha to his soul mate Wilhelm.

Freud’s ambivalence towards women and his disillusionment with his own marriage are barely concealed themes of “‘Civilised’ Sexual Morality and Modern Nervous Illness” (1908) and “The Taboo of Virginity” (1918). His unflattering take on the heterosexual sex act, in Crews’ words, was that it is “hygienically restorative but degrading” (page 423).

In “Wisdom, beyond Consolation”, a review of Freud: An Intellectual Biography, by Joel Whitebook (QR, 21st September 2017) there is passing reference to Freud’s alleged affair with his wife’s sister, Minna. Professor Crews predictably devotes a chapter to this issue. But in the end, who cares? For all his failings, Freud surely deserved a more appreciative and generous biographer.

Dr Leslie Jones is the Editor of QR

Closely reasoned and revealing. Not disharmonious either with the argument of Lesley Chamberlain in her book of some years ago, ‘Freud: the Secret Artist’. The interesting wannabe urge in the man, shared in varying ways with his fellow Viennese of the epoch, obviously Stefan Zweig but doubtless many others…

His essays on civilization &c and his basis notion of “id-ego-superego” are still worth considering. He was a indeed a bit of a Fraud, and even more so whole Psychoanalysis Racket especially in the USA, but his ideas must be examined almost entirely on their own (de)merits and clinical reportage, irrespective of his personal faults. Adler had a much more sensible idea of human self-mastery and a more successful (therefore less lucrative) medical therapy. Jung also is more interesting as an essayist on civilization &c despite his weakness for occult mumbo-jumbo.

The cultural problem in recent years has been the attempt to mix Freud with Marx, though the subsequent postmodernism has shot them each up their own primary erogenous zone.