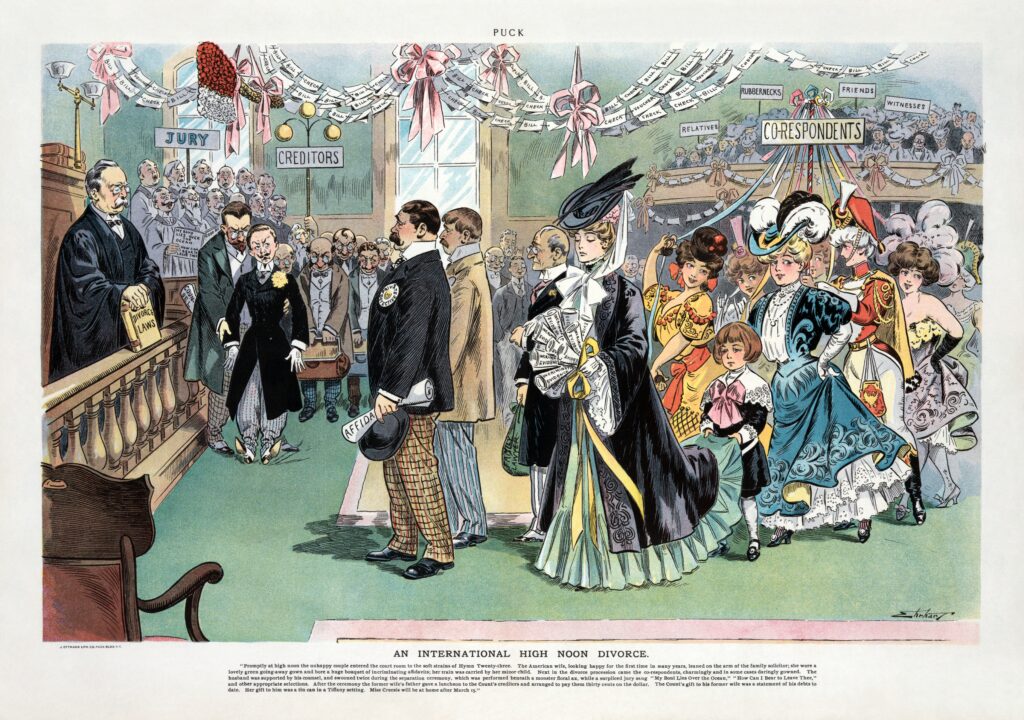

Samuel D Erhart, An International High Noon Divorce

Marriage Matters

by Bill Hartley

Periodically the question of divorce reform features in the media. The last serious attempt to bring about change was by John Major’s government which apparently ignored what students of constitutional law are taught: that no minority administration should ever attempt to legislate on a moral issue. Admittedly Major’s government wasn’t quite in a minority but his majority following the 1992 general election was only 21 and the government should have first calculated how many Roman Catholic MPs there were in the Parliamentary Conservative Party; the sort of people likely to have viewed it as a moral issue. Anyway it was all rendered academic because Major lost the 1997 general election. Tony Blair’s government was smart enough to sidestep a moral issue. As a consequence, the Matrimonial Causes Act (1973) remains the law on divorce in this country.

Critics of the existing law (and Major’s government based its intentions on this) insist that divorce shouldn’t be ‘fault based’. They are presumably in favour of a petitioner being able to approach the county court and see the marriage dissolved without any evidential checks being left in place. Of course there are the financial and child care arrangements and doubtless a court would wish to be satisfied that these had been established. Overall the desired approach would be to reduce divorce to an administrative process lightly overseen by the courts whose task would be to record that the marriage had been dissolved. However, just because the current law has been in operation for 47 years doesn’t necessarily mean it is bad law. The Law of Property Act for example, a far more complex piece of legislation, continues to regulate the sale of houses and no-one is crying out for it to be reformed simply because it is nearly a hundred years old and society has changed.

The 1973 Act sets out five heads under which a divorce may be obtained: adultery, desertion, behaviour, separation for a year (both parties agreeing) or five years (if both parties don’t agree). Very occasionally, the newspapers report one of those peculiar cases where an aggrieved respondent refuses to admit a petition and holds out for the full five year term. It does suggest sheer bloody mindedness but if the petitioner can’t come up to the mild civil standard of proof required to obtain a divorce under ‘behaviour’ then something strange is probably going on.

There is a sense that since the Major government’s abortive attempt political tacticians have baulked at the idea of reform because they know how it will play in certain sections of the media who are likely to accuse the government of making divorce ‘easier’. The problem with attempting to take blame out of divorce is that it flies in the face of human nature. After all, there may be blame to be apportioned, even if it has no effect on the outcome. To quote Ayesha Varday, president of family law firm Varday’s in 2016, ‘divorce doesn’t have to ruin lives but no matter how you legislate it probably will’. Would ‘no fault’ divorce really make a difference? Those with a desire to take the law out of this aspect of human relations and reduce it to a soulless administrative process may be deluding themselves.

The 1973 Act keeps alive (or just about) the adversarial concept which is an integral part of our legal system. It could be asked: why does this matter? The alternative view was set out by Sir James Mumby President of the Family Law Division of the High Court in 2014. He asked: ‘has the time not come to legislate to remove all concepts of fault as a basis for divorce and to leave irretrievable breakdown as the sole ground?’ The suggestion being then that financial remedies should be uncoupled and separately reviewed, replacing the decree nisi and decree absolute with a single notice of divorce.

Admittedly, defended divorces hardly ever happen these days and a YouGov For Resolution poll showed that 69% of those surveyed agreed with the no fault concept. The poll also showed that 27% of divorcing couples who asserted blame admitted that the allegation of fault wasn’t true but had been the easiest option. Although this was a high percentage of people in favour of no fault, it makes one wonder if they would still hold the view if actually in that situation. Clearly though the existing law is open to manipulation but for it to work both parties need to be privy to this.

What seems to be overlooked by those seeking reform is the collateral damage caused by divorce. American studies have shown the effect on children; the significant correlation between offspring of divorced couples and school under achievement, drug abuse and higher suicide rates. There is also the economic damage and the loss of security experienced by divorcing couples.

Interestingly what has been creeping up evidently unnoticed by the reformers is a change in attitudes towards marriage. According to the Ministry of Justice the number of divorces has fallen by almost a third in the last 14 years. Fewer people are marrying but more are staying married. There seems to be a raised awareness of the emotional and financial damage caused by divorce. Despite its faults the Act reflects the fact that divorce is a serious business not to be entered into lightly and for this reason there is a case against reform. The fact that some couples are prepared to manipulate erodes but doesn’t eliminate the concept of proof which remains an important part of our legal system. The back stop of a waiting period between the decrees nisi and absolute provides scope for people to think again before taking the final step. Having to actually apply for a decree absolute suggests that those who drafted the Act were conscious of the need to put in place a final chance to recant. The Act may not be law at its best but at least it remains a workable attempt to reflect the seriousness of divorce and the collateral damage it can do.

BILL HARTLEY is a former deputy governor in HM Prison Service and he writes from Yorkshire

Like this:

Like Loading...

Marriage Matters

Samuel D Erhart, An International High Noon Divorce

Marriage Matters

by Bill Hartley

Periodically the question of divorce reform features in the media. The last serious attempt to bring about change was by John Major’s government which apparently ignored what students of constitutional law are taught: that no minority administration should ever attempt to legislate on a moral issue. Admittedly Major’s government wasn’t quite in a minority but his majority following the 1992 general election was only 21 and the government should have first calculated how many Roman Catholic MPs there were in the Parliamentary Conservative Party; the sort of people likely to have viewed it as a moral issue. Anyway it was all rendered academic because Major lost the 1997 general election. Tony Blair’s government was smart enough to sidestep a moral issue. As a consequence, the Matrimonial Causes Act (1973) remains the law on divorce in this country.

Critics of the existing law (and Major’s government based its intentions on this) insist that divorce shouldn’t be ‘fault based’. They are presumably in favour of a petitioner being able to approach the county court and see the marriage dissolved without any evidential checks being left in place. Of course there are the financial and child care arrangements and doubtless a court would wish to be satisfied that these had been established. Overall the desired approach would be to reduce divorce to an administrative process lightly overseen by the courts whose task would be to record that the marriage had been dissolved. However, just because the current law has been in operation for 47 years doesn’t necessarily mean it is bad law. The Law of Property Act for example, a far more complex piece of legislation, continues to regulate the sale of houses and no-one is crying out for it to be reformed simply because it is nearly a hundred years old and society has changed.

The 1973 Act sets out five heads under which a divorce may be obtained: adultery, desertion, behaviour, separation for a year (both parties agreeing) or five years (if both parties don’t agree). Very occasionally, the newspapers report one of those peculiar cases where an aggrieved respondent refuses to admit a petition and holds out for the full five year term. It does suggest sheer bloody mindedness but if the petitioner can’t come up to the mild civil standard of proof required to obtain a divorce under ‘behaviour’ then something strange is probably going on.

There is a sense that since the Major government’s abortive attempt political tacticians have baulked at the idea of reform because they know how it will play in certain sections of the media who are likely to accuse the government of making divorce ‘easier’. The problem with attempting to take blame out of divorce is that it flies in the face of human nature. After all, there may be blame to be apportioned, even if it has no effect on the outcome. To quote Ayesha Varday, president of family law firm Varday’s in 2016, ‘divorce doesn’t have to ruin lives but no matter how you legislate it probably will’. Would ‘no fault’ divorce really make a difference? Those with a desire to take the law out of this aspect of human relations and reduce it to a soulless administrative process may be deluding themselves.

The 1973 Act keeps alive (or just about) the adversarial concept which is an integral part of our legal system. It could be asked: why does this matter? The alternative view was set out by Sir James Mumby President of the Family Law Division of the High Court in 2014. He asked: ‘has the time not come to legislate to remove all concepts of fault as a basis for divorce and to leave irretrievable breakdown as the sole ground?’ The suggestion being then that financial remedies should be uncoupled and separately reviewed, replacing the decree nisi and decree absolute with a single notice of divorce.

Admittedly, defended divorces hardly ever happen these days and a YouGov For Resolution poll showed that 69% of those surveyed agreed with the no fault concept. The poll also showed that 27% of divorcing couples who asserted blame admitted that the allegation of fault wasn’t true but had been the easiest option. Although this was a high percentage of people in favour of no fault, it makes one wonder if they would still hold the view if actually in that situation. Clearly though the existing law is open to manipulation but for it to work both parties need to be privy to this.

What seems to be overlooked by those seeking reform is the collateral damage caused by divorce. American studies have shown the effect on children; the significant correlation between offspring of divorced couples and school under achievement, drug abuse and higher suicide rates. There is also the economic damage and the loss of security experienced by divorcing couples.

Interestingly what has been creeping up evidently unnoticed by the reformers is a change in attitudes towards marriage. According to the Ministry of Justice the number of divorces has fallen by almost a third in the last 14 years. Fewer people are marrying but more are staying married. There seems to be a raised awareness of the emotional and financial damage caused by divorce. Despite its faults the Act reflects the fact that divorce is a serious business not to be entered into lightly and for this reason there is a case against reform. The fact that some couples are prepared to manipulate erodes but doesn’t eliminate the concept of proof which remains an important part of our legal system. The back stop of a waiting period between the decrees nisi and absolute provides scope for people to think again before taking the final step. Having to actually apply for a decree absolute suggests that those who drafted the Act were conscious of the need to put in place a final chance to recant. The Act may not be law at its best but at least it remains a workable attempt to reflect the seriousness of divorce and the collateral damage it can do.

BILL HARTLEY is a former deputy governor in HM Prison Service and he writes from Yorkshire

Share this:

Like this: