Teatro San Carlo, 1830, credit Wikipedia

Time’s Sequestered Treasure

Donizetti in the 1830’s, 7-CD Box set, £32, from Opera Rara, reviewed by David Truslove

Founded in 1970, Opera Rara is a goldmine for anyone wanting to explore the remoter corners of 19th and early 20th century opera. Donizetti, in particular, has been a long-term favourite with the company which aims to document all his music through recordings and performing editions. This limited edition boxed set, released in September 2021 to mark Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary, comprises three seldom performed works (spread over seven discs) spanning Donizetti’s career-defining decade of the 1830s. Made from recordings between 1977 and 2005, this significant release, remastered with exceptionally fine sound, includes a specially commissioned essay by Roger Parker and a synopsis for each opera. Complete libretti are also available as downloads. As usual with Opera Rara, these rarities on the company’s own label enjoy outstanding singing, playing and conducting.

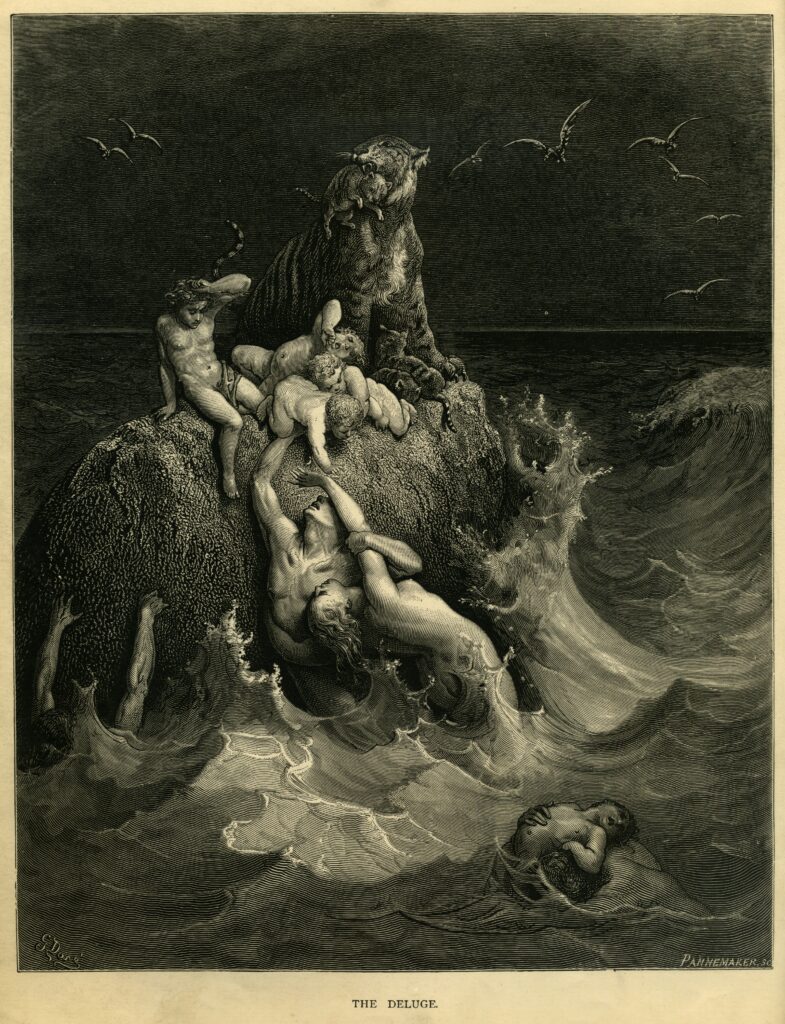

Gustave Doré, The Deluge, credit Wikipedia

Il diluvio universale (The Great Flood) is the second of four operas Donizetti composed in 1830. It’s something of an oddity and belongs to a vogue for biblical epics bearing kinship with Rossini’s Mosè in Egitto and Verdi’s Nabucco. Determined to stage a work during Lent, Donizetti combines the sacred and profane and peoples Il diluvio with a collection of imagined characters in which the unwavering faith of Noah (named Noè) is pitched against the hedonistic Babylonian court of Cadmo. His wife Sela shares in Noè’s belief of an impending flood, whilst also embracing the fleshly delights of Babylon. But at the close, when she renounces God, the first thunderclap erupts. Built onto this framework is Sela’s rival Ada whose efforts to ensnare Cadmo are doomed when Sela attempts to salvage her marriage.

Despite Donizetti’s strenuous efforts over the narrative – reading literary works on the Flood and providing his librettist with a sketched-out scenario – the work had an unpromising premiere on 6 March at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. The last act’s staging prompted derision, and a near disastrous mistiming from the principal soprano added to the work’s mixed reception. The audience sensed the absence of accumulating tension in the closing scene where infectious rhythms hardly match a sense of impending cataclysm. While Il diluvio found favour in some circles, the work was ‘buried’ until Opera Rara’s 2005 recording. If the work’s dramatic flaws remain unresolved, there’s much to enjoy, notably some impressive arias, duets and extended ensembles. Never mind that dramatic tension is undermined by Donizetti’s toe-tapping jauntiness, as when Cadmo’s followers attempt to destroy the Ark. Don’t expect much solemnity, though Noè’s harp-accompanied prayer in Act 2 provides a welcome change of mood.

Opera Rara’s excellent cast is supported by vivid playing from the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Giuliano Carella, who delivers much edge-of-the-seat excitement. Among the principals, Mirco Palazzi brings considerable gravitas to Noè, with a warm mahogany tone and impressing most when urging God not to destroy the world in the finely shaped phrases of ‘Dio tremendo’ [2/10]. His antagonist Cadmo is well served by Colin Lee. Initially sounding effortful, there’s no shortage of passion when berating his wife Sela and he’s on captivating form in both ‘Ah perfida’ [1/14] and ‘Non profferir parola’ [2/5]. The lyric soprano Majella Cullagh convinces early on as Sela with her showstopping cabaletta ‘Perchè nell’alma’ [1/5], her coloratura effortlessly dispatched. Cullagh and Lee form a compelling partnership, their domestic confrontation unravels with a thrilling climax, yet judging from its uplifting music one might think they were celebrating the renewal of their marriage vows. Both Simon Bailey (Jafet) and Roland Wood (Artoo) make persuasive contributions, but it’s the expressive range of Manuela Custer as the venomous Ada who consistently captures the ear. Whether in sweet-toned musing or demonic raging, she savours her role and there’s no doubting her fabulous technique. She is gloriously exultant in ‘Saràlieve il mio tormento’ [2/3], smoothly sailing across the registers, fruity low notes displayed to advantage.

Two years after Il diluvio, and with another half dozen scores behind him, Donizetti found only partial success in Milan with Ugo, conte di Parigi (Hugo, Count of Paris) – this collection’s jewel in the crown. Following its premiere (his first at the Teatro alla Scala) on 13 March 1832, a critic found the cast visibly weary, having ‘barely had the opportunity to study their roles passably’. No surprise if the principals were ill-prepared when most of them had recently appeared in Bellini’s Norma that had run for some thirty-four performances. Ugo was taken off after a short run and vanished for over a century until Opera Rara’s world premiere studio recording in 1977.

Luigi Deleidi, Donizetti e Amici, credit wikipedia

Notwithstanding cuts to the libretto owing to political insensitivities – implied regicide, failed insurrections, betrayal and suicide of a future queen – Donizetti’s convoluted plot is no adequate reason to dismiss a work rich in musical felicities and developing characterisation. Its colourful Sinfonia is by turns portentous and scintillating. Vocal pyrotechnics may not be Donizetti’s priority here, but Ugo exhibits a gratifying sense of forward momentum, its dramatic tensions superbly controlled. There are rumbunctious choruses alongside numerous ensembles (sparks fly in Act Two’s ‘Hai ben pensato’) and several moving duets, such as the touching poison scene.

Located in 10th century France and set against a background of political intrigue, Ugo centres on the relationship between Princess Bianca of Aquitaine, her husband-to-be Luigi V (the young King of France) and Ugo, the King’s loyal regent, whom she secretly loves. But she doesn’t reckon with the love between Ugo and her sister Adelia, and when she calls off the wedding Luigi suspects her of infidelity and imprisons Ugo much to the delight of the scheming courtier Folco. Only when Ugo suppresses a revolt against Luigi is he released. Fuelled by jealousy of Amelia and Ugo, Bianca plots to poison them but instead takes her own life. Just to complicate things, Luigi’s mother Emma is consumed by guilt in relation to her late husband’s death. While her remorse remains an enigma, it provides one of the opera’s most affecting episodes.

Less enigmatic are these inspirational performances from a glittering A-list. In the title role is the burnished tenor Maurice Arthur, whose red-blooded Ugo soars over the cast in the call-to-arms number ‘L’orifiamma ondeggi al vento’ [1/7]. Passion informs his declarations to Adelia and his prison scene is no less idiomatic. There’s a terrific partnership between Arthur and a fresh-voiced Yvonne Kenny (making her recording debut) as Adelia. She’s on compelling form when expressing her feelings for Ugo, throwing herself at the stratospheric ‘Se tu m’ami’ with fabulous control [2/6]. Della Jones is a well-defined Luigi V, determined to avenge a murdered father in a fiercely sung entrance aria and yielding when suspicions about Ugo are unfounded in the placatory ‘Prova mi dai’ [3/9]. Janet Price, as Bianca, commands attention with singing of febrile intensity and great dignity. Her cabaletta ‘No, che infelice’ [1/10] is exemplary, woes and hopes communicated with blazing conviction. Elsewhere, Christian du Plessis’s dark baritone is tailor-made for Folco, while Eiddwen Harrhy, as an emotionally disturbed Emma, is wonderfully intimate in her extended encounter with Bianca, a passage not unrelated by convention to the ‘mad scene’ in Anna Bolena. Conductor Alun Francis coaxes stylish playing from the New Philharmonia Orchestra, with an acute ear for balance and a firm grip on the score’s musical trajectory.

Donizetti had high hopes for his historical drama L’assedio de Calais (The Siege of Calais) even before it was premiered in 1836, a year after Lucia di Lammermoor. Conceived ‘in accordance with French taste’, it was intended to be his entrée into the Paris opera – the most keenly sought-after musical destination in Europe. But his new work had a run of some thirty-eight performances before it sank without trace, unperformed until its first modern revival at Bergamo in 1990. An outing at the Wexford Festival occurred a year later and, thereafter, there have been productions by the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and, in 2013, performances by English Touring Opera. Their staging excised the entire last act regarding it dramatically redundant, as too did Donizetti when he revised the work in 1837. Never one to mince his words, Richard Morrison in The Times declared the last act ‘piffle, musically and especially dramatically’. Whilst this cut ensures dramatic integrity, it denies two purely orchestral passages (originally conceived for a Parisian audience) and the brief appearance of the English King and Queen. In this 1988 recording, Opera Rara thankfully perform the work in its entirety.

For its somewhat fanciful excursion into the early period of the Hundred Years War, L’assedio de Calais is set in 1347 (the year after the battle of Crécy) when the French port is besieged by the English army under Edward III. Six burghers of Calais, including the mayor Eustachio, volunteer their lives in exchange for a lasting peace. The English Queen (named as Isabella rather than Philippa of Hainaut) is so moved by their valour that she persuades the King to end the siege and spare their lives. After two tension-filled acts of English brutality and French stoicism, the jubilant conclusion of Act 3 seems anti-climactic. That said, the arrival of the Queen brings a timely change of atmosphere. Donizetti’s marches have a certain swagger. With this tremendous cast, it barely matters that these grim realities are incongruously set to such ebullient music, especially when Donizetti’s vocal demands are met with fearless conviction. Disregarding the occasional mismatch, one cannot fail to appreciate the bel canto and choruses sung with patriotic fervour.

The Siege of Calais, 1838, François-Èdouard Picot, credit Wikipedia

Christian du Plessis measures up well as an honourable Eustachio: his noble baritone is both authoritative and tender, touchingly so when addressing the plight of a starving Calais, and when offering prayers for the lives of the martyr’s children. As his rabble-rousing son, Aurelio has most of the vocal prime cuts and Della Jones (in another trouser role) perfectly catches the mood of this firebrand, cherishing the bravura writing. Promising ‘eternal glory’ for those that defend the city, her ‘Giammai del forte’ [1/9] is marvellously invigorating, and she’s never more passionate than when dismissing the English messenger in response to the terms of surrender. Amongst the ensemble numbers, the farewell hymn closing Act 2 where the burghers prepare for their execution is a masterstroke of dramatic catharsis. There are wonderful duets for Aurelio, the best of which involve his long-suffering wife Eleonora sung by a winsome Nuccia Focile. Their partnership is nowhere better than when singing of their hopes for Calais after an agreement has been reached for a parley. ‘La speme un dolce palpito’ from Act 2 [2/2] is memorable. Rico Serbo claims attention for his clarion-voiced Giovanni and is well matched by John Trevelyan’s suave Edmondo. More familiar names include Norman Bailey, Russell Smythe and Eiddwen Harrhy.

Opera Rara has done a sterling job with this operatic reboot, its engineers sharpening audio definition to highlight what are involving and thoroughbred performances. As overlooked gems, these operas make rewarding listening and reveal Donizetti as a musical dramatist of originality and imagination. Their relevance in his oeuvre cannot be overlooked and these dedicated performances will be cherished by devotees of fine singing.

Portrait of the composer Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848) by Giuseppe Rillosi

David Truslove is a Music Critic