Salt’s Mill

The Walls of Jericho

Bill Hartley blows his trumpet

Since the nineteenth century the expansion of our cities has seen settlements on the outskirts absorbed into the urban area. Occasionally though a town avoids this trend and manages to retain a distinct character. Topography can sometimes play a part in allowing this to happen and there is a good example to be found in the Yorkshire Pennine country.

Not everyone would favour living on an exposed site more than 1200 feet above sea level. This is a location which still carries a sense of isolation, even though it overlooks the City of Bradford. The railways never made it here, being defeated by the gradient. Closest was the old Great Northern Railway which climbed to some impressive heights on its network but was defeated by Queensbury, now part of the Bradford Metropolitan District. The station lay 400 feet below the town. Here, up to the 1960s, stood one of the strangest examples of railway architecture, a triangular station built that way to accommodate three lines which needed to find their way around the hills. Because the valley bottom sites had been taken by other lines they were known to train crews as the Alpine Route.

Queensbury lies on a spine dividing the Aire and Calder valleys and getting up there from any direction involves a steep climb. Unsurprisingly, the Tour de Yorkshire cycle race was routed through these parts. Queensbury retains its own distinct character and shows no signs of being gentrified. It is soot blackened, insular and on an icy winter’s day when denuded of people, a slightly sinister place. Agriculture never really worked around here. On the outskirts are small fields with drystone walls and crumbling farmhouses. Surprisingly farming still clings on, mostly sheep rearing and some horse breeding; there is little else which can be done with such marginal land. At one time though the land did have a greater value and in the nineteenth century there was said to be around 30 quarries operating in the district. This easily accessible stone became the main building material and all of this effort is reflected in the Queensbury townscape. There are few brick buildings here and the local gritstone was used both for walls and even as roofing material on the weaver’s cottages.

The Queensbury skyline is dominated by the great chimney of the Black Dyke Mills. Architecturally this place could define Dark Satanic and no-one has ever bothered to clean off the soot. To a considerable extent the mill created the town and many other buildings owe their existence to the company. The man behind this was John Foster (1798-1879). His career encompassed the transition from domestic weaving to the mills. Originally he outsourced work to the cottagers who wove with handlooms. Then he brought the cottagers into his mill. Foster was a philanthropic mill owner and the town contained shops and leisure facilities provided by the company, plus of course the famous Brass Band. It may seem strange that Foster should choose such a remote location for his huge mill. The reason was because his family had been small farmers there and he owned the land. In addition there were deposits of coal under the property; farming and its close connection with mining and quarrying combined to provide the materials that Foster needed. The business is still in operation, though the company has now moved to Bradford. The industrial units which operate out of the old premises just about keep the place going.

This High Pennine country has produced some strange place names. Just beyond Queensbury on the road to Thornton is the aptly named hamlet of Mountain. Then there are clusters of cottages with Biblical names such as Jericho, Jerusalem and the perhaps ironic World’s End. Religion has been deeply ingrained here and still appears to hang on. The Anglicans of course have the parish church and the Catholics a toe hold but for those wanting something more charismatic there is a newcomer, the Life Church. Interestingly for such a remote place, choice always seemed to be available. For those seeking a no frills religion there is a Bethel Baptist church dating back to the nineteenth century. The Moravians have been here that long too. Religion also influenced the naming of another now vanished local landmark. In the hamlet of Egypt stood the Walls of Jericho, two immense drystone constructions flanking a narrow road. The walls were erected to hold back waste rock from a local quarry and driving between them was said to be an uncomfortable experience. All that rock was being held in place by nothing more than the skills of local artisans whose usual work would have been erecting field boundaries. By the Eighties, the walls were in a dangerous state. Enter the local authority with a dubious estimate of how much it would cost to stabilise them. The walls are now long gone and have entered local folklore.

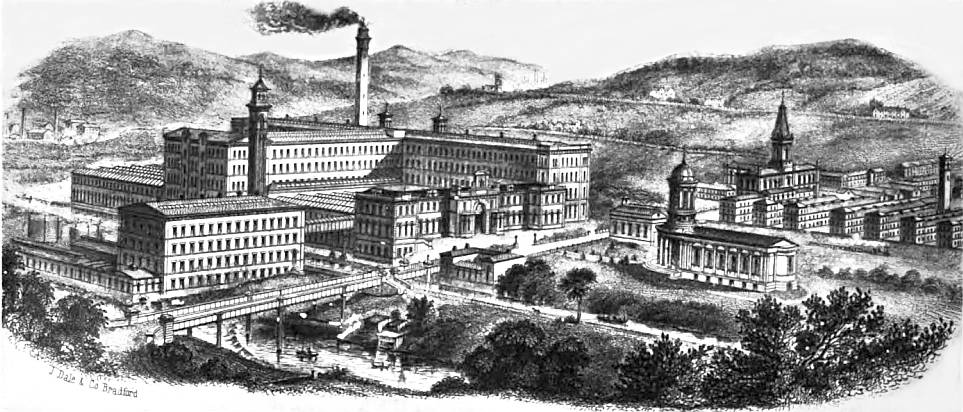

Descending from Queensbury towards Bradford one option is to go through Thornton, a village whose main claim to fame is that the Bronte sisters were born there. The Reverend Patrick Bronte seems to have spent much of his career moving from one grim West Riding location to another before ending up in Haworth. Thornton marks the descent from the bleak country around Queensbury into the more urbanised district of Shipley. Close by is Titus Salt’s massive mill at Saltaire, built to a neo-Florentine design. In further contrast to the austere Black Dyke Mills, it has been sandblasted back to a warm honey colour which it never knew in its industrial heyday. To find it when entering Shipley from Thornton, turn left just after the Precious Glimpse Baby Scanning Studio.

Saltaire and its model industrial village are heavily promoted by the tourist trade. For a different view of how life used to be lived, a trip up to Queensbury would be an option.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Walls of Jericho

Salt’s Mill

The Walls of Jericho

Bill Hartley blows his trumpet

Since the nineteenth century the expansion of our cities has seen settlements on the outskirts absorbed into the urban area. Occasionally though a town avoids this trend and manages to retain a distinct character. Topography can sometimes play a part in allowing this to happen and there is a good example to be found in the Yorkshire Pennine country.

Not everyone would favour living on an exposed site more than 1200 feet above sea level. This is a location which still carries a sense of isolation, even though it overlooks the City of Bradford. The railways never made it here, being defeated by the gradient. Closest was the old Great Northern Railway which climbed to some impressive heights on its network but was defeated by Queensbury, now part of the Bradford Metropolitan District. The station lay 400 feet below the town. Here, up to the 1960s, stood one of the strangest examples of railway architecture, a triangular station built that way to accommodate three lines which needed to find their way around the hills. Because the valley bottom sites had been taken by other lines they were known to train crews as the Alpine Route.

Queensbury lies on a spine dividing the Aire and Calder valleys and getting up there from any direction involves a steep climb. Unsurprisingly, the Tour de Yorkshire cycle race was routed through these parts. Queensbury retains its own distinct character and shows no signs of being gentrified. It is soot blackened, insular and on an icy winter’s day when denuded of people, a slightly sinister place. Agriculture never really worked around here. On the outskirts are small fields with drystone walls and crumbling farmhouses. Surprisingly farming still clings on, mostly sheep rearing and some horse breeding; there is little else which can be done with such marginal land. At one time though the land did have a greater value and in the nineteenth century there was said to be around 30 quarries operating in the district. This easily accessible stone became the main building material and all of this effort is reflected in the Queensbury townscape. There are few brick buildings here and the local gritstone was used both for walls and even as roofing material on the weaver’s cottages.

The Queensbury skyline is dominated by the great chimney of the Black Dyke Mills. Architecturally this place could define Dark Satanic and no-one has ever bothered to clean off the soot. To a considerable extent the mill created the town and many other buildings owe their existence to the company. The man behind this was John Foster (1798-1879). His career encompassed the transition from domestic weaving to the mills. Originally he outsourced work to the cottagers who wove with handlooms. Then he brought the cottagers into his mill. Foster was a philanthropic mill owner and the town contained shops and leisure facilities provided by the company, plus of course the famous Brass Band. It may seem strange that Foster should choose such a remote location for his huge mill. The reason was because his family had been small farmers there and he owned the land. In addition there were deposits of coal under the property; farming and its close connection with mining and quarrying combined to provide the materials that Foster needed. The business is still in operation, though the company has now moved to Bradford. The industrial units which operate out of the old premises just about keep the place going.

This High Pennine country has produced some strange place names. Just beyond Queensbury on the road to Thornton is the aptly named hamlet of Mountain. Then there are clusters of cottages with Biblical names such as Jericho, Jerusalem and the perhaps ironic World’s End. Religion has been deeply ingrained here and still appears to hang on. The Anglicans of course have the parish church and the Catholics a toe hold but for those wanting something more charismatic there is a newcomer, the Life Church. Interestingly for such a remote place, choice always seemed to be available. For those seeking a no frills religion there is a Bethel Baptist church dating back to the nineteenth century. The Moravians have been here that long too. Religion also influenced the naming of another now vanished local landmark. In the hamlet of Egypt stood the Walls of Jericho, two immense drystone constructions flanking a narrow road. The walls were erected to hold back waste rock from a local quarry and driving between them was said to be an uncomfortable experience. All that rock was being held in place by nothing more than the skills of local artisans whose usual work would have been erecting field boundaries. By the Eighties, the walls were in a dangerous state. Enter the local authority with a dubious estimate of how much it would cost to stabilise them. The walls are now long gone and have entered local folklore.

Descending from Queensbury towards Bradford one option is to go through Thornton, a village whose main claim to fame is that the Bronte sisters were born there. The Reverend Patrick Bronte seems to have spent much of his career moving from one grim West Riding location to another before ending up in Haworth. Thornton marks the descent from the bleak country around Queensbury into the more urbanised district of Shipley. Close by is Titus Salt’s massive mill at Saltaire, built to a neo-Florentine design. In further contrast to the austere Black Dyke Mills, it has been sandblasted back to a warm honey colour which it never knew in its industrial heyday. To find it when entering Shipley from Thornton, turn left just after the Precious Glimpse Baby Scanning Studio.

Saltaire and its model industrial village are heavily promoted by the tourist trade. For a different view of how life used to be lived, a trip up to Queensbury would be an option.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Share this:

Like this: