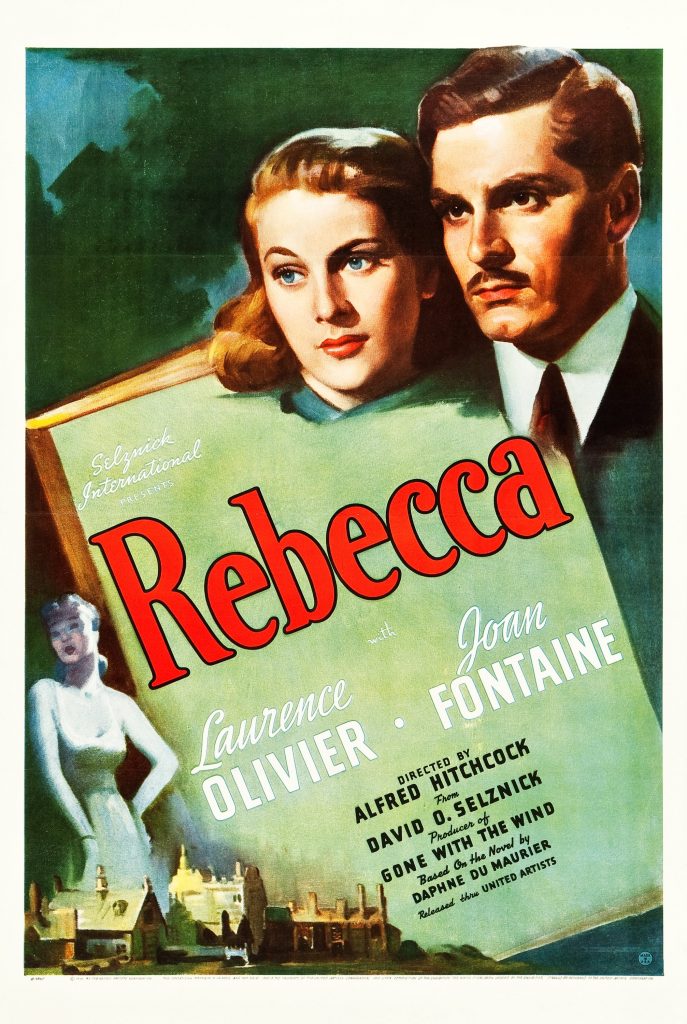

Rebecca (1939 poster)

Talking Pictures

by Bill Hartley

Anyone in search of tedious game shows, threadbare repeats and sales of junk jewellery is well catered for on British television. The sheer number of channels is bewildering and difficult to navigate. More means worse but persistence can pay off and for those willing to work their way through the wilderness of multiple channels there is one gem to be found.

‘The past is another country they do things differently there’: the quotation might well have been written for the Talking Pictures channel (Freeview 81), which has been in operation for three years. Welcome to a world close in time yet which shows how enormously life in this country (and indeed in the United States) has changed. Everyday life, manners, opinions and prejudices are perfectly preserved on film. In an era of on demand television and encouragement to binge on box sets, this channel takes us back to an era when cinema dominated and television was the new upstart.

Talking Pictures provides an entry into a half forgotten world; a place where information, plot and dialogue mattered even if much of it now seems amateurish to the modern viewer. It features British and American pictures from the thirties up to the seventies, augmented by public information films and television shows from the fifties and sixties. There are hard bitten cops, bomb damaged British streets but a sense that institutions are still solid and reliable. Here, you will find Green Line buses, incessant smoking, tail coated waiters and unrefrigerated beer.

The quality varies. On the same day as Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) was shown, Silver Fleet (1943), a creaky wartime propaganda piece starring Ralph Richardson, was also featured. Whilst the Nazis had by then been demonised in British cinema, the director came up with a novel way of making them seem worse. During a scene memorable for the wrong reasons, a senior Nazi is depicted with truly vile table manners. It is so hypnotically awful that the trance is only broken when the actor reaches for a napkin.

Whilst the channel shows plenty of forgettable B movies, look beyond the stilted dialogue and the suspect plots into a London of foggy streets, seedy boarding houses and street musicians. Detectives drive through light traffic in shiny black Austins and Rileys. People pull over to park with little difficulty and ladies wear hats in restaurants. In Unpublished Story (1942), Valerie Hobson and Richard Green stoically maintain their conversation whilst German bombs fall on London. Eventually this intrudes and Hobson comments; ‘I used to think war was something that happened to soldiers, sailors, airmen and….. foreigner’s’. As a concession to the mayhem in the East End, they replace their headgear with steel helmets when leaving the restaurant.

From across the Atlantic come films starring such forgotten actors as Broderick Crawford, one of the heaviest of the heavies. Whilst British detectives were restrained and professional, their US counterparts had cynicism as part of the job description. ‘Who’s the pigeon?’ Crawford asks of the corpse lying on a rain soaked street. Crawford was never leading man material but he looked as if he could sock someone on the jaw. Talking Pictures doesn’t overlook the ladies either. Some were once household names but are now almost forgotten, except by film buffs: a tearful Susan Hayward or perhaps the superb Barbara Stanwyk, baddest of the Bad Girls. The latter, in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), pushes her aunt down the stairs and then tries to persuade her boyfriend to kill her husband. The Bad Girls were always blonde and invariably smoked.

The channel also shows BFI ‘Shorts’, which hark back to a time when a visit to the cinema comprised a full evening’s entertainment. Often these are films telling the British about themselves both at work and play. One of these covers the Lancashire cotton industry and a huge amount of detail is crammed into just fifteen minutes. Evidently the film makers presumed that the viewer would take an intelligent interest and possessed sufficient attention span. In the 1940s, there was no sense of dumbing down or of patronising an audience. The commentator notes approvingly that many of those depicted are descendants of people who were working in the industry when Crompton’s spinning jenny was invented. Elsewhere we see the British braving the weather at a seaside resort, sitting on deckchairs beneath grey skies whilst their children in woollen swimsuits risk hypothermia in the chilly sea.

In the immediate post war era, the British liked to see films about themselves. This was exploited in Holiday Camp (1947) in which various characters arrive onsite. The wily businessman Billy Butlin loaned his camp at freezing Filey for filming. It’s worth watching to see what people were prepared to endure. The dining room looks as relaxed as a communal meal in a prison and single men and women were accommodated in sorry chalets with complete strangers. The impression is of military accommodation for civilians. It is the respectability of the ‘campers’ which enables so many strangers to coexist in harmony; the exception being Dennis Price masquerading as a squadron leader, whilst hiding from the law. Sporting a double breasted blazer and cravat, he is as inconspicuous as a peacock in a hen house.

Much of the output comes from the long defunct Merton Park studios in South Wimbledon. Having begun by making second feature films, the studio moved into what is now a staple of British television, the crime show. Then, as now, true crime is an audience puller and none more so than the Scotland Yard series which began in the early fifties. Each show was introduced by the suave and slightly sinister Edgar Lustgarten, talking on camera from what appears to be his study. His introductions were generally underpinned by the same theme: criminals might be clever but tended to overlook some vital detail which would eventually be noticed. The omniscient detective (always well attired) would fetch up in some distant part of the country to lend his expertise to the baffled locals. Junior officers would be despatched to undertake Herculean tasks without any thought for their welfare, a crisp ‘very good sir’ being their parting comment. Both detectives and criminals always wore a collar and tie and with the villain arrested, it fell to Lustgarten to end the show, often remarking with satisfaction that the outcome was the gallows.

Each episode provided a sense that all was right with the world once more and that order had been restored. Public officials may not have been any better then than now but they looked and acted as if they were. This is a world of once recognisable types: well-meaning vicars, bossy landladies, and sinister colonels who live in country houses. A world where both criminals and detectives wishing to remain inconspicuous will stand on otherwise empty streets wearing a trench coat whilst pretending to read a newspaper. Some transatlantic glamour was sometimes provided by an unknown American actor as an entertaining foil to the stuffy British.

This harmless channel has unhappily attracted the attention of Ofcom. Failing to appreciate that films made early in the last century tend to come with political incorrectness as standard, the maiden aunts at Ofcom have criticised the channel for ‘dated racial comments’, overlooking it’s mission to cover film history. Thankfully, Talking Pictures has thus far ignored this criticism.

BILL HARTLEY is a former deputy governor in HM Prison Service and writes from Yorkshire

The Quarterly Review is a free, online journal. We have no source of income other than readers’ donations. If you enjoy reading QR, please consider making a one-off or regular contribution today in order to secure our future.

Go to the Donations page from the Home page and use the PayPal link.

Agreed, Bill – some excellent classics on channel 81 – I remember seeing a rare Michael Caine and Omar Sharif film, The Last Valley (set in a ravaged 17th century European kingdom) a couple of months ago; and (in contrast) some old travel/public information films about Cornwall and the Norfolk Broads.

Just watching the 1953 film, Genevieve – on Channel 81 (all about the London to Brighton vintage car run). It stars Kenneth More and Dinah Sheridan, and every time something disastrous happens, the actors respond with “blast” or “how beastly”. The manners and the appearance of England as recorded in this film are a complete contrast with the society of 2018. In fact, it is difficult to believe – from the Eastenders, push-and-shove world of today – that we live in the same country as that depicted in the film.

Sad to say, I taught the present Ofcom boss Sharon White at a Leytonstone school, one of the cleverest and most pleasant pupils in some 30 years of teaching in very different schools in three education authorities. Poor Sharon – enforcing the “equality, diversity & inclusion” nonsense like the history re-writers in “1984”.

It seems that those enforcing the “equality and diversity” agenda (i.e. you mustn’t be English, or British) are a sort of ideological Health and Safety squad. As such, they are rightly and relentlessly lampooned by Richard Littlejohn in The Daily Mail – the country’s best-selling conservative newspaper.

One can, though, turn the tables on the “diversity” agenda – by pointing out that the watering down and obliteration of ancestral cultures creates a less interesting, less diverse world. With no archetypes left, there can be no true diversity. Everywhere becomes the same. And also, the enforcement of “diversity” as defined by the commissars seems only to include the “first nation” peoples (to use a pc term) of the United Kingdom. Little is done to interest newcomers in the diverse culture, ways, art and history of England and the British Isles – so “diversity” truly fails on all counts.

A great pity that this social engineering is happening under a Conservative government. What was once the preserve of the Town Hall Trotskyites of the 1980s, has now moved into the very language of government, education, the Armed Forces and all commerce. One can only buy or sell, gain high office – or any office – if the person subscribes to “diversity”; diversity – so called, being a very different thing from the normal, civilised, everyday English way of getting on with, being pleasant to, and tolerating others.

Settled down to watch the 1944 Bernard Miles film, Tawny Pipit, on the Talking Pictures channel yesterday – the film being a completely harmless rural piece, with comical moments, the whole story concerning a local battle to defend a rare pipit’s nest (from armoured vehicle exercises, Ministry of Agriculture incursions on the downland etc). I was quite amazed when, at the beginning, a sign appeared across the screen telling the viewer that the “following film contains some language which viewers may find offensive”! I wondered, at first, if the sign had been misapplied by the Freeview authorities at channel 81 – whether they had confused Tawny Pipit with a much more modern, violent film, possibly a Terror or Horror Pipit (set in downtown LA, or the 1960s’ Bronx or something like that). But no. As the film played through, I began to realise what the warning must have been about: Bernard Miles’s character, a stubborn, retired colonel (who helps to save the pipit) has a line about “many foreigners having come to England in the past” (he is comparing the pipit with newcomers to the country) and that “they can’t help being foreigners”! Or possibly, the scene where (again) the Bernard Miles character turns to the local vicar, and says of a visiting Russian female soldier: “Fine figure of a woman, that!”

To think that Tawny Pipit, and such obviously humorous, reactionary comments (even by 1944 standards) should qualify the film for a health warning is beyond belief – but shows how far political correctness has gone in this country. How could any rational person be remotely offended by Tawny Pipit?

When I was a younger teenager in the “imaginary England” of the early 1950s I used to go to the pictures with my parents, before I preferred taking girls, and I well remember us returning from a usual Thursday night visit to the Chingford Odeon, with its then-familar cinema smell, chuckling over “Genevieve” as we took fish&chips home afterwards in the dark, so neighbours would not see our “common” eating in the street. Oh, “nostalgia” (the next thought-crime, if we are to follow “Sir” Vince Cable”)! — but unfortunately for the memory-holers & multicultural re-writers, left indelibly in print and photo. John Gregson, Kay Kendall, Dinah Sheridan, and of course Kenneth More whose place in English film stays along with John Mills, Anthony Quayle, Celia Johnson, Jean Simmons, Ralph Richardson, Anna Neagle, Virginia McKenna, Jack Hawkins and Alec Guinness (together in “The Prisoner” banned at Venice because if its offensive anti-communism) and unforgettable “minor stars” like Stanley Holloway, Geoffrey Keen, Peter Wyngarde and Richard Wattis. The Odeon no longer exists but near where it stood the mother of Leslie Phillips was later inclusively murdered reportedly by a vibrant couple of diverse muggers.

Some of the old black-and-whites had the best stories and characters. I see the current “This England” is asking for nominations for best films, and those who know Stuart Millson can guess his first Kentish choice. The magazine features a favourite of mine, “Went the Day Well”. Another was “The Lady Vanishes” (despite the toy used at the opening) and of course “In Which We Serve” (with its perfect joke about Neville Chamberlain), though which I saw some years AFTER it was made, like “Things to Come” with its magnificent Oswald Cabal peroration.

However, my favourite altogether (despite the artificial village set at the end) is “Random Harvest”, an MGM production, with English-born actors Ronald Colman and Greer Garson; I recommend it to all patriotic ladies (however few remain) with handkerchiefs available.

At the going down of our nation, we shall remember them.

Yes, David – it has to be the 1944, A Canterbury Tale (by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger) – a vision of a true England and a sovereign Britain in wartime; of the settled people of our country, loyal to their traditions; and a visiting American serviceman who discovers that his community in Oregon is not that much different from the people of “Chillingbourne” (possibly the real-life Kent village of Chilham). Wartime pilgrims discover sunlight and blackberries on the North Downs – and begin to hear voices and musical instruments from Chaucer’s time. And the local JP and amateur historian, Mr. Colepepper, defends his campaign of pouring knowledge into people’s heads: “knowledge of our country and love of its beauty”.

The Remainiacs, social engineers, modernist town-planners, anti-countryside “developers”, pc commissars and multiculturalists, dedicated to the overthrow of everything we understand by the words “England” and “Great Britain”, may be vocal – and may never go away.

But as the old song says: “There’ll ALWAYS be an England.” And there are enough of us left who stand for this cause.

I have just been reading the updated new version of “Abolition of Britain” by Peter Hitchens. He was always a pessimist as well as a puritan but a brilliant fact-packed writer. He says that our England is now dead. It is quite true that when “Always be an England” is played at the Cenotaph, the managers accompany it with a wheelchair parade, and not only the Empire but the Country Lanes have taken a knock. But we are NOT finished yet. Take heart from the intelligent YOUNG faces of the patriots just across the Channel, and let’s work for a counterpart revival here, before Lee Jasper’s promised “Black Britain” (“The last days of a white world”, Guardian, 3 September 2000, online) can actually arrive.

A splendid outing last night on ‘Talking Pictures’ for that English classic, The Admirable Crichton – starring Kenneth More and Cecil Parker (freeview, channel 81). Quite a weepy moment when Crichton (now the governor of the island where he and his aristocratic “masters” have been shipwrecked) is about to be married – but, on the horizon, an English vessel comes into view… thus ending their blissful, remote existence. Why can’t we make films like this any more? Gone are the actors of those days, with their wit and good manners. No more Kenneth Mores.

Such a wonderful contrast between this film – and the contemporary, pc slop served up by the BBC, such as the new ‘Dr. Who.’ A BBC promotional poster says of the new Dr. Who series: “It’s about time.” (Ha ha – so amusing that double meaning: the programme concerns time, but it’s “about time” that we had a female Dr. Who.) So far, though, people seem to be switching off – bored and repelled by the tedious politically-correct storylines and little leftist lectures throughout the script. Wish we could programme the Tardis to go back to the days of Jon Pertwee.

‘A Challenge for Robin Hood’ (1967) – director Pennington Richards – has just begun on the Talking Pictures TV channel. Once again, a public health warning was broadcast before the film: “Some viewers may find scenes in this film distressing.”

I simply cannot understand why anyone could find such a film distressing. Perhaps it’s the sword-fights, or Friar Tuck bashing someone over the head with an ale jug? Maybe if there was swearing in the film, it would be less offensive to a modern audience?

I watched – and was impressed by – the new TV adaptation of Watership Down, broadcast on BBC1 during Christmas. However, the voices of the main characters were a little disappointing. The first animation of the story from 1978 came with the voices of John Hurt, Richard Briers, Joss Ackland et al – perfectly suited to the timbre and location of the story. Somehow, somewhere, over the last 40 years, we have lost that fruitier, distinctive tone of voice.

Glad to see that BBC Four broadcast two classic M.R. James ghost stories from the early-1970s, possibly the golden age of British television. The Vaughan Williams excerpt in Lost Hearts, in one rural scene, touched the heart; and The Ash Tree evoked all the loneliness of England.

I regret to observe that “pc slop” is becoming the dominant ideology of BBC productions and TV “stuff” generally, as elsewhere.

Many years ago a Conservative Party researcher called Julie Gooding at a public meeting noted the “leftist” drift in BBC news, drama, personnel, &c. I was encouraged as a youth to start a collection of evidence (South Africa and South Vietnam were the “easy” ones), which resulted in a dozen large cartons of documents and cuttings that were stored in a lock-up after we moved from London to Norfolk. Some time ago most of the contents were destroyed by a massive flood, but no-one in politics or journalism had shown interest in using the material. More recently and belatedly some authors have produced a few booklets, and Rod Liddle and a few other journalists moan in print.

All in vain? The official ideology is “equality, diversity, inclusion”. It is the ruling cult at the BBC which along with “The Guardian” is its chief agitprop mechanism. Those opposed to it are designated (ironically) “extremists”, usually “far right” ones (whatever that label “means”). Mother Theresa’s “government” has promised to “tackle” all forms of “non-violent extremism”, but does not and cannot produce a sensible “definition” other than “vocal opposition” to “democracy” and “respect” for “different beliefs”. It is a more serious development than the concept of “hate speech”. Humpty Dumpty becomes Big Brother, not just a tyranny but an arbitrary one.

A chilling look at a Britain in which most infrastructure and values have collapsed was broadcast by Talking Pictures TV last night (freeview channel, 81): the 1979 Quatermass, starring John Mills. Urban areas are no longer fit for civilised people – taxis look like riot vans – the para-military police are under constant fire. The remnant intellectual class live (through the power cuts and food shortages) in the far countryside, which is inhabited by hippies, known as the Planet People, who seek out stone circles…