Marx out of ten?

On May Day, Mark Wegierski wonders what remains of value in Marxist thought

Karl Marx and his intellectual collaborator and patron Friedrich Engels established a heritage of thought which is said today to be nearly-universally discredited, yet which has both today and historically also attracted a surprising variety of supporters and defenders, across virtually the entire spectrum of left, right, and centre.

The Marxian tradition is evidently more multivalent than its identification with the former East Bloc system, nominally called “Communist” — suggests. Marx might well have had some serious disagreements with the current-day Left – and most certainly with the current-day left-liberal establishment.

This essay endeavors to avoid either the simplistic condemnation of Marx common among some anti-Communists, as well as the panegyrics which had been de rigueur in the former Eastern Bloc — which, along with the various depredations of the system — have today reduced Marx’s intellectual cachet far more in East-Central Europe than in the United States, Canada, and Western European societies that never experienced the “worker’s paradise.”

There are a number of interpretations of Marx’s thought which may be termed “mainline” — and a number which may be termed “dissident.” Intellectually-speaking, Marx brought a certain zest into political philosophy, as well as a sharp style of writing that tries to tenaciously “get at” what certain political and philosophical pronouncements “actually say.” He may indeed be characterized as one of the modern “masters of suspicion.”

He combined in what was — at that time — a new, interesting way — philosophical thinking, the claim of being scientific, and what should accurately be called “ideology” or “polemics.” Some of the “mainline” aspects of Marx’s thought include his central concept of desire for human liberation, the ferocious condemning of economic inequality, and a doctrinaire atheism, materialism, and hatred of traditional religion. Indicatively, Marx’s chosen motto for his doctoral thesis was the quote from Shelley’s Prometheus – “Above all, I hate all the gods.”

However, Lenin’s elaboration of Marx’s “dictatorship of the proletariat” seems to have been little more than a carte blanche for the exercise of power of a narrow ruling group that was supposed to be putting Marx’s egalitarian dreams into reality. To borrow the Marxian terminology, the “ideological superstructure” of the promise of the Communist utopia at the end of the road — where the state would famously “wither away” — was utterly unreflective of the reality of the brutal, coercive, totalitarian “base.” The fact that Soviet Marxism-Leninism and Maoism arose in so-called “backward” societies like Russia and China suggest that they had more in common with what Marx had disparagingly termed “the Oriental mode of production” — rather than “scientific socialism.” The depredations of the North Korean, North Vietnamese, and Pol Pot regimes are well-known today. The reception of Marxism in Africa also led to massacres, and usually intensified the underlying problems of those societies. In Latin American societies, Marxism appeared to have acquired an almost romantic mystique, as typified by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

The reception of Marxism in America, Canada, and Western European countries was somewhat different from that in Russia — in the former societies, it seemed to truly have vast intellectual cachet and was apparently based on the appeal to “liberation” and “humane values.” The “liberation” aspects — especially in regard to the so-called Sexual Revolution — were given a huge play in the 1960s and post-1960s period, whereas over several decades of the Twentieth Century many people believed that what was somewhat imprecisely called Communism was simply about ensuring a decent life for the laboring masses. The fact that the imposition of Soviet Communism on Russia and especially on the East-Central European countries during World War II and its aftermath proceeded by means of mass slaughter and massive repression and indoctrination was generally ignored.

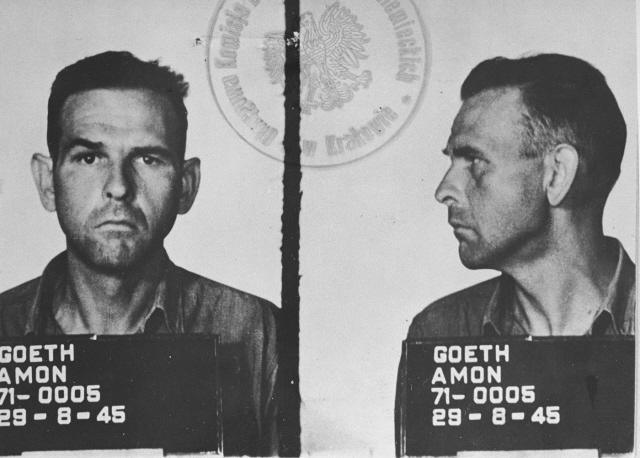

Paradoxically the highly-disciplined Marx-inspired parties and movements were admired by the far right in various European countries, especially France and Germany. Whereas ultra-traditionalists such as Oswald Spengler looked to the socialist parties as vehicles for conservative social restoration, the German Nazis (National Socialists) identified with the harsh, totalitarian as well as anti-Jewish and anti-Polish aspects of the Soviet Communist regime. It should be remembered that between August 1939 to June 1941, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were close allies, united by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The admiration of the Nazis for the Soviet regime was, of course, for mostly different reasons than those of the legions of Western liberal “pilgrims” who genuflected before Stalin because they perceived Soviet Communism as the “progressive” utopia.

Oswald Spengler

Among the more fruitful re-interpretations of Marxism were those carried out by the Frankfurt School (Adorno, Horkheimer, et al.). The Frankfurt School has now become a curiously bivalent tradition, which has inspired some of the most serious critics of what is considered the current-day “managerial-therapeutic regime” (such as Paul Piccone, the late editor of the New York-based scholarly journal, Telos) — as well as providing one of the strongest buttresses of that system, i.e., the theory of “the authoritarian personality.” The psychological critique of “personality” at its most pointed considers “authoritarian” political identifications a form of mental illness to be eradicated by mass conditioning, and, if it is discovered in an individual, to be “cured” by semi-coercive “therapy.” However, the Frankfurt School’s deep-level critique of consumerist, consumptionist society — which could be seen as one of their main contributions to intellectual inquiry — is clearly evocative of traditionalist cultural conservatism.

Another fruitful re-interpretation of Marx’s thought can be seen among the so-called “social conservatives of the Left” — such as William Morris, Jack London, George Orwell and Christopher Lasch. In the age of the pre-totalitarian and pre-politically-correct Left, John Ruskin, a nineteenth-century aesthetic and cultural critic, could say, “I am a Tory of the sternest sort, a socialist, a communist.” However, these figures could probably be placed more in the ambit of “utopian socialism”, “guild-socialism”, or “feudal socialism” — tendencies which were polemically condemned in Marx and Engel’s The Communist Manifesto.

Another interesting off-shoot of Marx’s thought is the Syndicalist system represented by Georges Sorel, as well as by varieties of Anarchist ideas. The Papal encyclical De Rerum Novarum certainly was a reaction to Marx’s thought — and so-called “Catholic social teaching” tried to embrace what were seen as the positive aspects of Marx’s critique of capitalism and of extreme social inequality, while avoiding its iconoclastic radicalism and potential for abuse by power-hungry ideologues. G. K. Chesterton’s Distributism and C. H. Douglas’ theory of Social Credit were two further attempts to maintain the rights of decent small-property holders and workers against the depredations of monopoly finance-capital, without recourse to violent dictatorship.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Given the apparent irrelevance of “classical Marxism” by the 1960s — especially in regard to such areas as its underdeveloped theories of psychology, art, religion, and literature, and its thin materialism — there arose varieties of “neo-Marxism.” The presence of “neo-Marxism” allowed for the countering of the more common criticisms of earlier Marxist thought, which were now simply categorized as describing a “vulgar Marxism” that the new Marxist theorists did not themselves hold. In the attempt to “rescue” a more subtle Marx, great attention was paid to Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 – which were fully published in English only in 1959.

There were also, among the leading innovations of neo-Marxism — especially in the thought of Frantz Fanon and Herbert Marcuse – the embrace of social outcasts, racial and sexual minorities, and the Third World, in the face of what were characterized as the “embourgeoified” white working classes. What classical Marxism had disparagingly termed the “lumpenproletariat” now became to a large extent the focus of revolutionary energies for the neo-Marxist theorists.

Also important for neo-Marxism was Antonio Gramsci, whose claim to fame was the idea — in contrast to classical Marxism — that the “ideological superstructure” would actually bring into being the social and economic facts of “the base” — hence the need for “an intellectual war of position” and “the march through the institutions” in order “to capture the culture.” The existence of, and need to engage in, “cultural warfare” — can be seen as an idea with great cachet in virtually every part of today’s political spectrum. Indeed, it is arguable that what was actually happening in the 1960s in America was the creation by the now-deracinated haute-bourgeoisie of new ideological structures that would allow it to re-establish its dominance over the working majority. The triumph of the working majority in America — when a factory-worker was able, by his own labor, to earn enough to support his wife and family — was to be short-lived.

These new ideologies combined counter-cultural lifestyles, mass media saturation, juridical and administrative social engineering, consumerism, and corporate capitalism, which led to ensuring again the hegemony of a narrow ruling group. Policies such as mass, dissimilar immigration and (what is now called) outsourcing were driven by the impulse to strengthen the consumerist-capitalist system — a system which was, of course, much different from nineteenth-century bourgeois capitalism.

Conversely, Paul Edward Gottfried, a leading American paleoconservative theorist, has argued that the Communists in the Soviet Union and East-Central Europe, as well as Communist party members in Western Europe, were, to a large extent, socially-conservative. Indeed, the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) (as the Communist party was formally called in Poland) after 1956 had certain nationalist elements. It may be remembered that the quasi-“Trotskyite” opposition to the PZPR in the 1960s, characterized the PZPR as “too nationalist”, “too traditionalist” and “too conservative” — in fact, they openly called it “fascist.” Indeed, it could be argued that the main thrust of the Mensheviks, Trotsky and his disciples, and such figures as Rosa Luxembourg has been to be more consistently anti-nationalist, anti-traditionalist, and anti-conservative than “mainline” Communism.

Gottfried’s central argument is that, as the Communist and former Communist Parties in Western and East-Central Europe mostly embraced capitalism, consumerism, multiculturalism, and anti-national high immigration policies, they objectively became less, not more “conservative”. The East-Central European Communist Parties’ embrace of capitalism also appears to have been characterized by the phenomenon of what is called “the empropertyment of the former nomenklatura” (in Polish: uwlaszczenie nomenklatury) – which was mainly achieved through the sell-out of state industries to former Communist party insiders and foreign companies at ridiculously low prices. So the former Communist party insiders have in many cases become fabulously wealthy, capitalist bosses.

It had also been suggested in the 1970s and 1980s that the Soviet and Eastern European Communist regimes — with their “ruling Party caste” (nomenklatura) were ripe for a “true Communist revolution.” Indeed, in many Western countries — though probably to a lesser extent in Poland — much of the rhetorical appeal of the Solidarity independent trade-union movement (which was said to be truly representing the Polish working class) was based on echoes of Marxist thought.

However, what can be said of the situation today, when the economic “shock-therapy” which supposedly represents capitalism, has bitten hard, especially in Poland? The contrasts of wealth and poverty in Poland have arguably increased beyond anything seen during the People’s Republic of Poland (PRL). It could be rhetorically asked, is now actually the time for a “true Communist revolution” in Poland?

It could be maintained that Marxism, like most ideological systems, conveys a partial truth. In the nineteenth century, who could in good conscience support the exploitation of decent working people by various luxuriously-living overlords? Serious and reflective traditionalist thought had always been opposed to the cruel impositions of various iniquities. The arising of the labor movement in the nineteenth century was precisely what was needed to counter the monstrous power of capital.

In the minds of many Western liberals, Communism became associated with “decent values.” As the recently caught elderly British woman-spy said of the Soviet Communists, “They only wanted to give medicine and food to their people.” Obviously, what has happened is that the idealism of nineteenth-century workers’ protests has been grotesquely transferred to Stalin’s regime.

Interestingly enough, the Western apologists for the Soviet Union were virtually at their apogee precisely during what was later called the Stalinist period. It appears that when the Soviet Union was at its most “utopian” — and claiming to create “a new human life” — support for it was the strongest among Western intellectuals. After it had become more authoritarian (for example, under Brezhnev) rather than totalitarian — it no longer excited the same degree of enthusiasm among Western intellectuals. One does see today, however, a return to aggressive defenses of Soviet Communism — and even of Stalin — among some Western Marxist intellectuals.

In the twentieth century, Western societies have moved through various wrenching social revolutions and transformations — whose radical nature is not always apparent to observers. In today’s consumerist, consumptionist society in America and Canada, the labor struggle is usually seen as part of a broader, left-liberal coalition of rich liberals and “recognized minority leaderships.” Traditionalists and members of the so-called “disaligned Left” such as Christopher Lasch would be hoping for a renewed labor struggle that could be detached from doctrinaire left-liberalism — and from its putative acceptance of the ruling structures of the current-day managerial-therapeutic regime.

If one is looking for what is good in Marx-inspired thought, there is clearly the aspect of social protest against exploitation. There is also the notion of comradely struggle for a better world. At the same time, persons struggling against injustice should be careful to properly identify what true injustice and victimization actually consist of, and to avoid falling into the trap of excessively-ranging ressentiment. For example, before the 1960s, the social democrats in most Western countries (such as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation party in Canada), while ferociously fighting for equality and the betterment of the working majority, accepted most elements of traditional nation, family, and religion as simply a part of pre-political existence, which they had no desire to challenge. They were thus economically socialist, but socially conservative. The causes which animate much of today’s Left (such as multiculturalism, feminism, gay rights, and cultural antinomianism) would have alienated many of them. There is clearly something inappropriate happening when a wealthy, privileged, left-liberal arrogantly condemns a decent, careworn, working man for the latter’s supposed racism, sexism, or homophobia.

In conclusion, in today’s world, when capitalism, as exemplified by globalization, is so overwhelmingly international (or transnational) and anti-traditional, the more independent-minded and less-politically-correct Left should be re-examining the importance of nations, nationalism, and nationhood as well as various traditionalisms, as part of the possible resistance to the incipient hypermodern dystopia.

MARK WEGIERSKI is a researcher and writer based in Toronto

Like this:

Like Loading...

.jpg)

Marx out of ten?

Marx out of ten?

On May Day, Mark Wegierski wonders what remains of value in Marxist thought

Karl Marx and his intellectual collaborator and patron Friedrich Engels established a heritage of thought which is said today to be nearly-universally discredited, yet which has both today and historically also attracted a surprising variety of supporters and defenders, across virtually the entire spectrum of left, right, and centre.

The Marxian tradition is evidently more multivalent than its identification with the former East Bloc system, nominally called “Communist” — suggests. Marx might well have had some serious disagreements with the current-day Left – and most certainly with the current-day left-liberal establishment.

This essay endeavors to avoid either the simplistic condemnation of Marx common among some anti-Communists, as well as the panegyrics which had been de rigueur in the former Eastern Bloc — which, along with the various depredations of the system — have today reduced Marx’s intellectual cachet far more in East-Central Europe than in the United States, Canada, and Western European societies that never experienced the “worker’s paradise.”

There are a number of interpretations of Marx’s thought which may be termed “mainline” — and a number which may be termed “dissident.” Intellectually-speaking, Marx brought a certain zest into political philosophy, as well as a sharp style of writing that tries to tenaciously “get at” what certain political and philosophical pronouncements “actually say.” He may indeed be characterized as one of the modern “masters of suspicion.”

He combined in what was — at that time — a new, interesting way — philosophical thinking, the claim of being scientific, and what should accurately be called “ideology” or “polemics.” Some of the “mainline” aspects of Marx’s thought include his central concept of desire for human liberation, the ferocious condemning of economic inequality, and a doctrinaire atheism, materialism, and hatred of traditional religion. Indicatively, Marx’s chosen motto for his doctoral thesis was the quote from Shelley’s Prometheus – “Above all, I hate all the gods.”

However, Lenin’s elaboration of Marx’s “dictatorship of the proletariat” seems to have been little more than a carte blanche for the exercise of power of a narrow ruling group that was supposed to be putting Marx’s egalitarian dreams into reality. To borrow the Marxian terminology, the “ideological superstructure” of the promise of the Communist utopia at the end of the road — where the state would famously “wither away” — was utterly unreflective of the reality of the brutal, coercive, totalitarian “base.” The fact that Soviet Marxism-Leninism and Maoism arose in so-called “backward” societies like Russia and China suggest that they had more in common with what Marx had disparagingly termed “the Oriental mode of production” — rather than “scientific socialism.” The depredations of the North Korean, North Vietnamese, and Pol Pot regimes are well-known today. The reception of Marxism in Africa also led to massacres, and usually intensified the underlying problems of those societies. In Latin American societies, Marxism appeared to have acquired an almost romantic mystique, as typified by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

The reception of Marxism in America, Canada, and Western European countries was somewhat different from that in Russia — in the former societies, it seemed to truly have vast intellectual cachet and was apparently based on the appeal to “liberation” and “humane values.” The “liberation” aspects — especially in regard to the so-called Sexual Revolution — were given a huge play in the 1960s and post-1960s period, whereas over several decades of the Twentieth Century many people believed that what was somewhat imprecisely called Communism was simply about ensuring a decent life for the laboring masses. The fact that the imposition of Soviet Communism on Russia and especially on the East-Central European countries during World War II and its aftermath proceeded by means of mass slaughter and massive repression and indoctrination was generally ignored.

Paradoxically the highly-disciplined Marx-inspired parties and movements were admired by the far right in various European countries, especially France and Germany. Whereas ultra-traditionalists such as Oswald Spengler looked to the socialist parties as vehicles for conservative social restoration, the German Nazis (National Socialists) identified with the harsh, totalitarian as well as anti-Jewish and anti-Polish aspects of the Soviet Communist regime. It should be remembered that between August 1939 to June 1941, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were close allies, united by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The admiration of the Nazis for the Soviet regime was, of course, for mostly different reasons than those of the legions of Western liberal “pilgrims” who genuflected before Stalin because they perceived Soviet Communism as the “progressive” utopia.

Oswald Spengler

Among the more fruitful re-interpretations of Marxism were those carried out by the Frankfurt School (Adorno, Horkheimer, et al.). The Frankfurt School has now become a curiously bivalent tradition, which has inspired some of the most serious critics of what is considered the current-day “managerial-therapeutic regime” (such as Paul Piccone, the late editor of the New York-based scholarly journal, Telos) — as well as providing one of the strongest buttresses of that system, i.e., the theory of “the authoritarian personality.” The psychological critique of “personality” at its most pointed considers “authoritarian” political identifications a form of mental illness to be eradicated by mass conditioning, and, if it is discovered in an individual, to be “cured” by semi-coercive “therapy.” However, the Frankfurt School’s deep-level critique of consumerist, consumptionist society — which could be seen as one of their main contributions to intellectual inquiry — is clearly evocative of traditionalist cultural conservatism.

Another fruitful re-interpretation of Marx’s thought can be seen among the so-called “social conservatives of the Left” — such as William Morris, Jack London, George Orwell and Christopher Lasch. In the age of the pre-totalitarian and pre-politically-correct Left, John Ruskin, a nineteenth-century aesthetic and cultural critic, could say, “I am a Tory of the sternest sort, a socialist, a communist.” However, these figures could probably be placed more in the ambit of “utopian socialism”, “guild-socialism”, or “feudal socialism” — tendencies which were polemically condemned in Marx and Engel’s The Communist Manifesto.

Another interesting off-shoot of Marx’s thought is the Syndicalist system represented by Georges Sorel, as well as by varieties of Anarchist ideas. The Papal encyclical De Rerum Novarum certainly was a reaction to Marx’s thought — and so-called “Catholic social teaching” tried to embrace what were seen as the positive aspects of Marx’s critique of capitalism and of extreme social inequality, while avoiding its iconoclastic radicalism and potential for abuse by power-hungry ideologues. G. K. Chesterton’s Distributism and C. H. Douglas’ theory of Social Credit were two further attempts to maintain the rights of decent small-property holders and workers against the depredations of monopoly finance-capital, without recourse to violent dictatorship.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Given the apparent irrelevance of “classical Marxism” by the 1960s — especially in regard to such areas as its underdeveloped theories of psychology, art, religion, and literature, and its thin materialism — there arose varieties of “neo-Marxism.” The presence of “neo-Marxism” allowed for the countering of the more common criticisms of earlier Marxist thought, which were now simply categorized as describing a “vulgar Marxism” that the new Marxist theorists did not themselves hold. In the attempt to “rescue” a more subtle Marx, great attention was paid to Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 – which were fully published in English only in 1959.

There were also, among the leading innovations of neo-Marxism — especially in the thought of Frantz Fanon and Herbert Marcuse – the embrace of social outcasts, racial and sexual minorities, and the Third World, in the face of what were characterized as the “embourgeoified” white working classes. What classical Marxism had disparagingly termed the “lumpenproletariat” now became to a large extent the focus of revolutionary energies for the neo-Marxist theorists.

Also important for neo-Marxism was Antonio Gramsci, whose claim to fame was the idea — in contrast to classical Marxism — that the “ideological superstructure” would actually bring into being the social and economic facts of “the base” — hence the need for “an intellectual war of position” and “the march through the institutions” in order “to capture the culture.” The existence of, and need to engage in, “cultural warfare” — can be seen as an idea with great cachet in virtually every part of today’s political spectrum. Indeed, it is arguable that what was actually happening in the 1960s in America was the creation by the now-deracinated haute-bourgeoisie of new ideological structures that would allow it to re-establish its dominance over the working majority. The triumph of the working majority in America — when a factory-worker was able, by his own labor, to earn enough to support his wife and family — was to be short-lived.

These new ideologies combined counter-cultural lifestyles, mass media saturation, juridical and administrative social engineering, consumerism, and corporate capitalism, which led to ensuring again the hegemony of a narrow ruling group. Policies such as mass, dissimilar immigration and (what is now called) outsourcing were driven by the impulse to strengthen the consumerist-capitalist system — a system which was, of course, much different from nineteenth-century bourgeois capitalism.

Conversely, Paul Edward Gottfried, a leading American paleoconservative theorist, has argued that the Communists in the Soviet Union and East-Central Europe, as well as Communist party members in Western Europe, were, to a large extent, socially-conservative. Indeed, the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) (as the Communist party was formally called in Poland) after 1956 had certain nationalist elements. It may be remembered that the quasi-“Trotskyite” opposition to the PZPR in the 1960s, characterized the PZPR as “too nationalist”, “too traditionalist” and “too conservative” — in fact, they openly called it “fascist.” Indeed, it could be argued that the main thrust of the Mensheviks, Trotsky and his disciples, and such figures as Rosa Luxembourg has been to be more consistently anti-nationalist, anti-traditionalist, and anti-conservative than “mainline” Communism.

Gottfried’s central argument is that, as the Communist and former Communist Parties in Western and East-Central Europe mostly embraced capitalism, consumerism, multiculturalism, and anti-national high immigration policies, they objectively became less, not more “conservative”. The East-Central European Communist Parties’ embrace of capitalism also appears to have been characterized by the phenomenon of what is called “the empropertyment of the former nomenklatura” (in Polish: uwlaszczenie nomenklatury) – which was mainly achieved through the sell-out of state industries to former Communist party insiders and foreign companies at ridiculously low prices. So the former Communist party insiders have in many cases become fabulously wealthy, capitalist bosses.

It had also been suggested in the 1970s and 1980s that the Soviet and Eastern European Communist regimes — with their “ruling Party caste” (nomenklatura) were ripe for a “true Communist revolution.” Indeed, in many Western countries — though probably to a lesser extent in Poland — much of the rhetorical appeal of the Solidarity independent trade-union movement (which was said to be truly representing the Polish working class) was based on echoes of Marxist thought.

However, what can be said of the situation today, when the economic “shock-therapy” which supposedly represents capitalism, has bitten hard, especially in Poland? The contrasts of wealth and poverty in Poland have arguably increased beyond anything seen during the People’s Republic of Poland (PRL). It could be rhetorically asked, is now actually the time for a “true Communist revolution” in Poland?

It could be maintained that Marxism, like most ideological systems, conveys a partial truth. In the nineteenth century, who could in good conscience support the exploitation of decent working people by various luxuriously-living overlords? Serious and reflective traditionalist thought had always been opposed to the cruel impositions of various iniquities. The arising of the labor movement in the nineteenth century was precisely what was needed to counter the monstrous power of capital.

In the minds of many Western liberals, Communism became associated with “decent values.” As the recently caught elderly British woman-spy said of the Soviet Communists, “They only wanted to give medicine and food to their people.” Obviously, what has happened is that the idealism of nineteenth-century workers’ protests has been grotesquely transferred to Stalin’s regime.

Interestingly enough, the Western apologists for the Soviet Union were virtually at their apogee precisely during what was later called the Stalinist period. It appears that when the Soviet Union was at its most “utopian” — and claiming to create “a new human life” — support for it was the strongest among Western intellectuals. After it had become more authoritarian (for example, under Brezhnev) rather than totalitarian — it no longer excited the same degree of enthusiasm among Western intellectuals. One does see today, however, a return to aggressive defenses of Soviet Communism — and even of Stalin — among some Western Marxist intellectuals.

In the twentieth century, Western societies have moved through various wrenching social revolutions and transformations — whose radical nature is not always apparent to observers. In today’s consumerist, consumptionist society in America and Canada, the labor struggle is usually seen as part of a broader, left-liberal coalition of rich liberals and “recognized minority leaderships.” Traditionalists and members of the so-called “disaligned Left” such as Christopher Lasch would be hoping for a renewed labor struggle that could be detached from doctrinaire left-liberalism — and from its putative acceptance of the ruling structures of the current-day managerial-therapeutic regime.

If one is looking for what is good in Marx-inspired thought, there is clearly the aspect of social protest against exploitation. There is also the notion of comradely struggle for a better world. At the same time, persons struggling against injustice should be careful to properly identify what true injustice and victimization actually consist of, and to avoid falling into the trap of excessively-ranging ressentiment. For example, before the 1960s, the social democrats in most Western countries (such as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation party in Canada), while ferociously fighting for equality and the betterment of the working majority, accepted most elements of traditional nation, family, and religion as simply a part of pre-political existence, which they had no desire to challenge. They were thus economically socialist, but socially conservative. The causes which animate much of today’s Left (such as multiculturalism, feminism, gay rights, and cultural antinomianism) would have alienated many of them. There is clearly something inappropriate happening when a wealthy, privileged, left-liberal arrogantly condemns a decent, careworn, working man for the latter’s supposed racism, sexism, or homophobia.

In conclusion, in today’s world, when capitalism, as exemplified by globalization, is so overwhelmingly international (or transnational) and anti-traditional, the more independent-minded and less-politically-correct Left should be re-examining the importance of nations, nationalism, and nationhood as well as various traditionalisms, as part of the possible resistance to the incipient hypermodern dystopia.

MARK WEGIERSKI is a researcher and writer based in Toronto

Share this:

Like this: