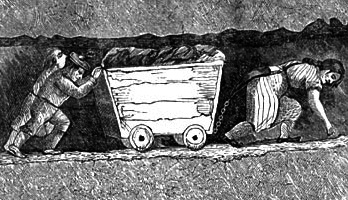

A hurrier and two thrusters, from The White Slaves of England (1853), J. Cobden, credit Wikipedia

Of Human Bondage

By Bill Hartley

In 2020, a group of students demanded that the David Hume tower at Edinburgh University be renamed. People will be wearily familiar with what comes next. Hume the philosopher and giant of the Enlightenment had allegedly committed the crime, in a footnote to an essay of his, of describing black Africans as inferior to white people. It has been argued that this was a misrepresentation of his work but even so the tower was duly renamed by the university authorities. Also in Edinburgh, the council has a ‘Slavery and Colonialism Review Group’. Good to know this is among the priorities of local government. North of the border they are considering changes to the school curriculum to focus on issues of slavery (Hume incidentally was against the idea of a British Empire). The Review Group reports that Scotland had one of the highest proportions of people benefiting from the ownership of slaves. Does this include Scots holding their own people in slavery? The Review Group might be surprised to learn that slavery was alive and well rather closer to home and arguably in conditions comparable to those caught up in the African trade.

Consideration is also being given to the creation of a National Museum for Slavery. This might provide an excellent opportunity for the Scots to learn what was going on in their own country, though it probably won’t happen, given the narrow definition of the term.

Hume himself called ‘Avarice the spur of industry’, and certainly in the Scottish coal industry during the 17th and 18th centuries there is much to support his view. The victims were of course white and this might prove inconvenient, since for some the term seems to be restricted to those of African descent. Even so, it is certainly not an exaggeration to say that life in the Scottish coal mining industry up to the end of the 18th century fitted the definition of slavery, both physically and legally. Should those considering the creation of a museum trouble to look, then there is plenty of source material available. For a contemporary perspective they could try ‘View of the Coal Trade in Scotland’ (1808) by Robert Baird, in which he wrote about the ‘severity of the toil performed by female coal bearers’ and used adjectives such as ‘revolting’ and ‘demoralising’. He noted that children began their pit lives at between six and eight years of age. Such conditions were of course to be found elsewhere in the British Isles, though only in Scotland was there the practise of taking infants underground. A sort of day care centre in darkness. Unlike the southern coalfields of Britain, north of the border it wasn’t just an unequal contest between the colliery owners and labour; political forces were the reason why miners, their wives and children were held in servitude.

The most scholarly study of the coal industry in Great Britain up to the end of the 18th century was undertaken by the American economic historian Professor J.U. Nef. His book ‘The Rise of the British Coal Industry’ (1932) remains the most exhaustive study of the coal trade covering that era. This is a monumental work of scholarship in two volumes, so it is perhaps surprising there appears to be such ignorance of slavery in Scotland, even in academia. But maybe those who look zealously for any evidence of support for slavery, no matter how tenuous, prefer to ignore what was going on in their home country, since the white variety doesn’t fit the narrative.

Nef noted that in the 17th century Englishmen called Durham and Northumberland the ‘Black Indies’ and adds that the term might have been applied with almost equal force to that part of Scotland bordering on the Firth of Forth. He writes of what he calls the ‘cleavage between capital and labour’ in England, where an association of miners might contract to operate a colliery. In Scotland a different arrangement evolved. Perhaps being an American and given when he was born, Nef may well have been better positioned than a British economic historian to make a comparison with plantation slavery.

By the 17th century, according to Nef, colliers were ‘set off sharply from the rest of the population’. This was how Scottish colliers (and salt workers) lived until the close of the 18th century. He cites sources such as ‘Slavery in Modern Scotland’ Edinburgh Review (1899) and ‘Slavery in the Coal Mines of Scotland’ Trans. of the Fed. Inst. of Mining Engineers (1897-98). The titles of both articles seem unambiguous.

By the end of the 17th century the miners and workers at salt pans (which generally belonged to the colliery owners) were the slaves of their employers. For example, he had the right to apprehend miners and inflict bodily punishment if they escaped from his works. He could sell them along with the works ‘as part of the gearing’ and this included wives and children who frequently worked with him.

The system was created by the Scottish coal owners to deal with a labour shortage. Originally, as in England, it was usually the case that a man was bound to serve for a year. However, many of the great landowners who of course owned the mineral rights, were members of the Scottish Privy Council and took steps to check the free movement of labour. The process began as early as 1606 when the Scottish Parliament passed a statute which declared that neither miners nor salt workers could change masters without a testimonial. In effect they served notice of an intention to retain their workmen in permanent captivity. By the reign of Charles II they were bound for life. A contemporary description seems to be a good definition of slavery:

‘Who are by severall Acts of Parliament astricted and bownd to serve and work in there coal and salt works during all the days of their lifetime’.

Significantly Nef adds that ‘their servitude cannot be regarded as a survival of agrarian serfdom’ and he makes a direct comparison with the United States. His view was that actual slavery of the type developed in the Scottish coal mines like that in the cotton plantations of the US, appears to be the product of a rapidly developing industry in the hands of landowner proprietors. The colliers are his servants: he provides them with a hovel in which to live and with meals to keep them from starving. Landowner proprietorship helps to explain why slavery developed in connection with the coal industry in Scotland but not in the North of England, where the mines were generally partnerships. Just as the political influence of the cotton planter was dominant in the southern states before the Civil War, so was that of the great landowners in 17th century Scotland.

There is a case for saying that if public funds are to be used for promoting an awareness of slavery, then the definition needs to be broadened. Scots people should be able to learn the inconvenient truth; that some of their forebears were as much victims of slavery as Africans.

William Hartley is a Social Historian

In 1752 David Hume expressed the opinion that white Europeans were more intelligent than black Africans.

In 2022 Uzonna Anele of “Talk Africana” (online) listed European IQs from Italy (102) down to Belarus (97) and African IQs from Sierra Leone (91) down to Equitorial Guinea (59).

Not to be confused with R. Cobden, the free trader.

T. Carlyle of course considered the plight of white workers more serious than that of black slaves, though C. Dickens is often misleadingly quoted on this comparison.

Whites were brought to north America as slaves or indentured servants between 1618 and 1855, at an early stage outnumbering blacks. They suffered just as much as blacks in transatlantic crossing according to impartial in-depth research, little known.

The first American slave owner was a black man called Anthony Johnson.

Whites were enslaved by non-whites in vast numbers before other whites bought slaves from non-white slavers; see e.g. Paul Craig Roberts, IPE, 12 March 2019, online, for some detailed documentation (there is more).

Slavery, including chattel slavery, has occurred at numerous times and places in human history, often accompanied by murder and torture no less cruel than what occurred in US Slavery or Jim Crow.

As many as 46 million men, women and children are currently estimated to be enslaved today in various ways in many countries.

There is a considerable literature on these subjects, including a small minority of effective critiques of the imposed “reparations” narrative. Particularly useful items for your library shelf are: Stephen Sanderson’s “Race & Evolution” and Jeremy Black’s “Brief History of Slavery”. Dare one mention also the online Daily Motion video made by the Wikipedia-denounced “controversial”, “notorious”, “alt-right” Stefan Molyneux, which is well worth downloading?