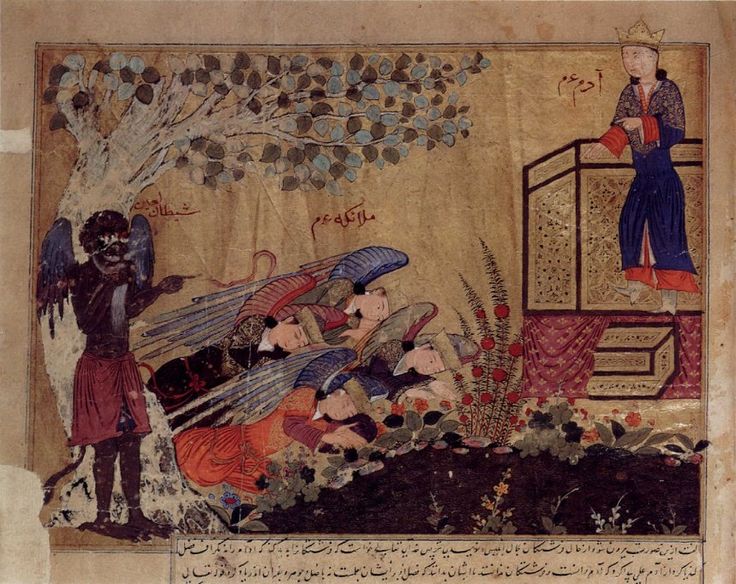

Adam and the Angels, watched by Iblis

Muslims are Reading the Bible Again

Gabriel Said Reynolds, The Quran & the Bible: Text and Commentary, Yale University Press, 2018, Pp. xviii, 1008, reviewed by Darrell Sutton

The decline of Christianity in the West has not impeded the continuous surge of attention Muslims give to the Quran in the East. In small pockets of Europe, the revival is spearheaded by persons born or raised in eastern hemispheres. Devotees of extremist views, of whatever religion, read their text passionately, even historically. Excessive ardor for truth sometimes takes them in violent directions. These facts are often concealed from an increasingly self-indulgent populace.

At the same time, the deterioration of Christian belief in recent decades is understandable. Unbelieving ecclesiastics do not inspire anyone, so sanctuaries sit empty. Although they would reckon their actions to be just, many politicians introduce legislation out of fear: fear of seeming to prefer one faith above another, fear of reprisal, fear of offending others etc.

Bible reading among Europeans and North Americans is not on the rise. There are exceptions, but look at the numbers. Yet the Hebrew Scriptures are held in high esteem by all adherents to Judaism. The Old Testament [in Greek and Hebrew], and the New Testament are believed by Christians to be God’s Word. Nevertheless, the falling away from faith continues apace.

Traditionally, Muslims have focused on the text of the Quran, ignoring the Holy Scriptures of the ‘People of the Book’, believing them to have been corrupted over time by Jews and Christians alike. Yet Muslims still take inspiration from their own honored texts. This is no longer the case among large segments of self-proclaimed Christian groups.

The academic study of the Bible has been carried on since the Enlightenment. Scholars of biblical texts routinely laud the latest researches with high praises. But usually little benefit accrues to society. Unbelief grows. The academic study of the Quran is a product of the researches of the last century and a half. Of them all, no studies have been more definitive than Theodor Noldeke’s The History of the Quran (1860). He investigated its passages with scrupulous precision. Although often moved in wrong directions by his attempts to be original, he applied critical techniques that remain popular in the academic study of the Quran but entirely unknown in the wider domains of the Muslim community.

Unlike certain supposedly Christian ministers, you will look in vain to find Imams who promote academic arguments in their mosques that encourage the degeneracy of popular belief in Islam or Muhammad’s prophethood. As a young person, I sat in classrooms in the Middle East day after day listening to Arabic lectures and studying the text of the Quran. The influence of the Bible was unmistakable in the shaping of accounts given during the earliest years of Muhammad’s revelations. A few people in Muhammad’s inner circle were acquainted with Bible texts. Afterward, the reading of them was no longer deemed necessary or desirable because the sacred recitations of the Quran were extant and applicable.

A century ago a scholar in the West, who made the Quran his field of study, approached his task with a knowledge of biblical texts. The same cannot be said of Western scholars today. Now Muslim scholars in Western universities, who at one time refrained from perusing Jewish and Christian texts when they read the Quran, are able to analyze for laymen the similarities and differences in their textual accounts in ways that are more authoritative than their Anglo speaking western colleagues, who are intent on promoting, through scholarship, unrealistic images of westernized Islamic ideals.

In effect, the academic study of the Bible and Quran jointly is no longer viewed as unseemly in contemporary academic circles. In society at large the matter is entirely different. Devout Jews are not going to read the New Testament when they can study the Talmud; conservative Christians are not going to apply their minds to reading the non-canonical texts like the Quran when Patristic texts are within reach; and the average Muslim will not expend precious time on the Old and New Testaments when each one can meditate on the vast Hadith literature.

Gabriel Said Reynolds thinks otherwise. His large tome will be read by students in university settings for sure. But to state an earlier point differently, the evangelical Christian, orthodox Jew, or devout Muslim likely will be uninterested in The Quran & the Bible’s (henceforth TQB) material and its arrangement.

The title is intriguing. Reynolds is no novice in this genre of study. He has published some very useful articles and informative reviews. He edited The Quran in its Historical Context (2007); and he authored The Quran and is Biblical Subtexts (2010) and The Emergence of Islam (2012). His labors within the International Qur’ānic Studies Association are irenic and well known. He is familiar with up to date researches on ancient texts of scripture and brings to his work the requisite acumen for explaining the Quran. He believes it

“includes multiple sources and a complicated history of redaction and editing” (p.5).

But since there are variants and several versions of it, and reviewers are approaching GSR’s volume critically, one wonders ‘which “Quran” is he expounding?’ Readers are barely introduced to the notion of variant readings; but see page 21, fn.41.

His base text (somewhat revised) is Ali Quli Qarai’s The Quran: with a Phrase-by-Phrase English Translation (2006). Reynold’s book lacks a fundamentalist or polemical tone. He believes his approach is critical.

The Introduction. This part requires the use of excerpts. The stated objective of the author is to instill a greater “appreciation” for the Quran’s meaning (p.2). No problem there, since the volume likely will be widely used in undergraduate liberal arts courses. He states:

My concern to read the Qur’ān independent of medieval traditions leads me to avoid a “chronological” approach to the text, that is, an approach which assumes that certain passages can be assigned to certain moments of Muhammad’s life (p.4).

His concern is peculiar and it prevents him from being able to explain the origins of certain Surahs and their specific uses of scripture. In his stated goal below, he says,

Yet our goal in the current work is to look at what the Qur’ān tells us, and not what later storytellers relate about the Qur’ān.

The force of that statement alone diminishes the volume’s authority and ensures that it’s use will be limited to the West, if it will be used at all in the middle east. What he misunderstands is that he too is one more storyteller in this long line of tradition. Besides, by focusing on the religious traditions of Late Antiquity, a period that Muslims label Jahiliyya/ignorance, Reynolds cuts himself off from the thoughts of the most conservative and erudite preservers of Islamic memory in order to make room for the eccentric conclusions of several of today’s scholars whose knowledge of the Arabic of the Quran and Islamic exegesis is questionable. He even has his doubts that the Arabic of the Quran represents a fully developed form of Classical Arabic (p.14). Yet what literary text from that period suggests that the Quran is an undeveloped form of the Classical Arabic language?

Further, he implies that the recently published book, ed., Seyyed Hussein Nasr, The Study Quran (2015), is too traditional in its approach (p.4,fn.17). Even here GSR is inconsistent. Like Nasr – yet with less passion – Reynolds seems to ascribe divinity and inspiration to Quranic texts, even though the same qualities are not ascribed by him to biblical passages; except at 9:30 he does argue that the Quran errs where it states the Jews say Ezra is the son of God. And he endeavors to explain that textual gaffe philologically. It is difficult for him, and will be for readers, to put an end to this matter with the notes he provides.

Relativism does not inform his comments, although he is concerned with contemporary thought. It is true that GSR does not utilize medieval commentaries as the commentators in The Study Quran do, but his compliance with modern critical theory on the Quran is no less traditional than Nasr’s use of medieval mindsets to explain various passages.

He chooses to employ the term “God” rather than “Allah” because he wanted

“to avoid the impression that the God of Islam is foreign or substantially different from other conceptions of God…” (p.7).

His confidence is unfounded. The pluralism insinuated there is patent but unknown in the Quran. Allah is unique in Quranic texts. He is depicted as one unlike any of the gods in the ancient near east. The connection to Jewish religion follows a strict line of descent from Abraham unto the Israelites: according to the Quran, the latter apostatized and rejected God’s revealed will. In the Quran, Jesus is only recognized as a notable prophet. Maintaining a robust doctrine of tawhīd/oneness, Allah in the Quran is unlike the Christian conception of deity because he is not a trinity of persons (a triune Godhead) and he has no son, as is publically noted in Arabic on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. There is absolutely no link at all between Allah and Greco-Roman deities. Neither Zoroaster’s god, nor the god of Manichaeism, was related to Islamic monotheism.

Therefore, to devotees of other religions and to Muslims, the God of Islam is foreign and substantially different from other conceptions of God. Using a common label like “God” does not alter that reality.

Moreover readers are told that

There is simply no compelling academic reason (theological reasons are of course another matter) to refuse categorically the possibility that the Qur’ān has multiple authors and/or editors (p.15).

The most compelling reason is that in Islam’s earliest history no one else is ever alleged to have written any of it. One can search the writings of the Rashidun Caliphs and all those historiographers down to the so-called Islamic Golden Age, and extant theories about multiple-authors are non-existent. In short, Reynolds remark lacks authority and is incapable of proof. A claim is not credible merely because it is conceivable.

Text and Commentary section. English translations of scripture are taken from The New Jerusalem Bible. Overall, no substantial correlation is made between Quranic and biblical verses. The theoretical intertextuality is overstated, certainly not proved. Indeed where similar characters and motifs are cited, GSR does not provide historical contexts to account for the differences in these hundreds of verses. This result stems from its avoidance of chronological studies.

There are some run-of-the-mill arguments too, such as that Surah 1 (Al Fatiha) and the Lord’s Prayer (pp.29-30) exhibit similarities. That contention is untrue. Muslims pray the Fatiha multiple times daily. It is used in Mosques worldwide for the call to prayer. Neither Jesus nor Christian tradition binds any Christian to perform daily recitations of The Lord’s Prayer or to pray it repeatedly as do Muslims. In fact, its exact wording need not be used when a believer prays to God the Father in Jesus’ name. The Lord’s Prayer is vital to Christianity but not like al Fatiha is to Islam.

There is a Roman Catholic undertone running through these pages. Readers need therefore to be reminded that Roman Catholicism is no longer the dominant form of Christian expression around the globe. But in his notes for 3:157-58, Reynolds treats of Holy War martyrs and their forgiveness of sin on account of their participation in war, a topic clearly dealt with in the Quran. Then on page 142, since the New Testament mentions no such thing, he falls back on middle age martyrdom in Roman Catholicism where Popes gave absolution of sins to warriors fighting on behalf of the Church. The association is bewildering to say the least (see also the note on 9:24). He presents the material as though a Papal decree is equivalent to an edict in the Quran.

At Surah 9:80 (p.316), it is written that

even if you plead forgiveness for them seventy times, God will never forgive them….

Somehow Reynolds relates the use of ‘seventy’ in that verse to the Lord’s reply to Peter in Mat. 18:21-22. There the conversation turns on how many times one should forgive a brother. In the Surah on Repentance, Allah rejects any type of intercession and seems obliged to hold his or her sins against the unbeliever; but in Matthew, Jesus obliges Peter to forgive regardless of the number of times one sins against him. The characteristics between the two deities show no correspondence. The number ‘seventy’ exists in both verses and is employed as a literary sign by Reynolds to bad effect.

At Surah 28:14 (pp.598-599), his discussion of Moses requires that he cite not scripture but Philo’s The Life of Moses. Then at Surah 74:30-31, in order to explain a remark in the verse about angels being keepers of the fire, Reynolds writes (p.869),

The Qur’ān’s declaration that there are nineteen angels (v.30) who watch over hell has confused both traditional Islamic and academic scholars. Paret wonders (Kommentar, 494) if the number nineteen might come from the addition of the seven planets (known in the classical period) with the twelve signs of the zodiac. The first book of Enoch speaks of 200 angels which descend to earth (on Mt. Hermon) and gives the names of their leaders, which in some manuscripts are numbered at nineteen (see 1 Enoch 6:7).

As is obvious, he cites an early Jewish text, 1 Enoch, rather than the Hebrew scriptures. That note is symbolic of what often is found in the commentary. Statements that he believes are characterized by allusion are firmed up by quoting non-canonical remarks, even though the book is titled The Quran & the Bible. Not surprisingly, the results of this research are disordered. Appraising it all would not be easy. At numerous places, he hits the nail on the head, as at 21:96 (pp.519-20) where Gog and Magog are mentioned. And he is able to note down the terms’ appearances in the Old and New Testament. Nevertheless he seems incapable of explicating those texts in either the Quran or the Bible. Theological discussion is his weak point.

The author is undoubtedly captivated by the Quran’s biblical background. But this publication is not a commentary in the conventional sense. There are no line-by-line observations on historical figures, word forms and so on. Page after page contain no notes at all. Taken as it is, this book is one professor’s take on what he perceives to be [non] biblical allusions referred to in the texts. The attempt at synthesis is grand. On an academic level this volume will promote a higher ascent toward unified dialogue; on a popular level, where adherents actually read the Quran or the Bible devotionally, this tool will not inspire confidence in scholarly discussion.

It is commendable to strive to create an academic resource that strengthens the bonds between worshippers in monotheistic religions by means of comparative examinations of texts. By doing so it is much easier to chip away at the foundational presuppositions of today’s “radical” Muslims. There must be a severance of extreme Islamic idealism from the principle texts that undergird their movements. Then again, what is deemed to be “radical” nowadays once was considered normative in other days and in other places. Reynold’s approach conceals that fact. This is why he dispenses with the views of medieval commentators and favours the consentient views of modernist scholars. A different picture is emerging. New readings of the Quran are spurring re-imagined contexts and analyses, but they will not erase historical truth for Muslims who understand their glorious past of Islamic conquest and proclamation in different ways.

As a textbook, readers will find much to savor, but in its present design it was subtly intended to keep contemporary readers from stumbling upon unseemly records of aggression in Arabic, Persian and Turkish texts that were written between the eighth and 19th centuries AD. Undoubtedly, Islam in the East needs a makeover. Were it not so, scholars in the West would not be working assiduously to generate new ways of reading the Quran. Fresh interpretations notwithstanding, it is imprudent to act as though the Islamic foundations upon which recent studies now are made do not also support textual structures whose divergent readings can produce equally competitive but radical understandings of a text. Novel opinions are fine if it can be illustrated why they are better than older ones. Since older ones are not given by Reynolds, historical comparisons cannot be made.

Hidebound traditions are hard to shake off. Clerics today within Sunni, Shiite, Sufi, Alawi, Ismaili arenas in the main do not read Quranic texts quite this way; and followers of Hanbali, Hanafi, Ja’fari, Maliki, Shafi’i, Zaidiyya, and a handful of other schools of law, will not be doing the kind of textual exegesis contained in this book. Professors exert great influence. Students at the University of Notre Dame will learn to read Islamic passages afresh when they study with GSR. But it is doubtful that they will be analyzing those same texts properly. Yale should be commended for producing a book that illustrates the construal of Islamic texts as Reynolds envisions them. Hopefully, though, they will soon issue reliable textbooks that plainly describe Islam as it is popularly practiced in its various sects.

At the close of the Introduction it was stated (p.15),

Ultimately, if the present book makes any argument, it is that the Qur’ān itself, by referring regularly to Jewish and Christian traditions, demands that its audience know those traditions.

I beg to differ. Over the last millennium and a half billions of Muslims have correctly practiced Islam without any awareness of the non-Islamic texts adverted to in this book. The expositions herein will not be proclaimed from minbars/pulpits anywhere outside of the West. But at least in the Occident, a few Muslims are reading the Bible again.

Darrell Sutton is a Pastor who resides in Red Cloud, Nebraska (USA). He received his diploma (Ijaaza) in Arabic and Quranic studies in Amman, Jordan. He publishes widely on ancient texts, both biblical and secular, along with specialized studies on the classical work and poetry of A.E. Housman

This is a welcome scholarly study in content and necessary length.

A fresh, careful, updated study of probable sources and factual vulnerabilities of the Quran would also be welcome,particularly in view of insurgent Islamism in former Christendom.

“The Study Quran” mentioned in its over 2000 thin, annotated pages is regarded by many Muslim scholars as too “ecumenical” rather than “traditional”; but is a welcome asset on the shelves of students of religion.