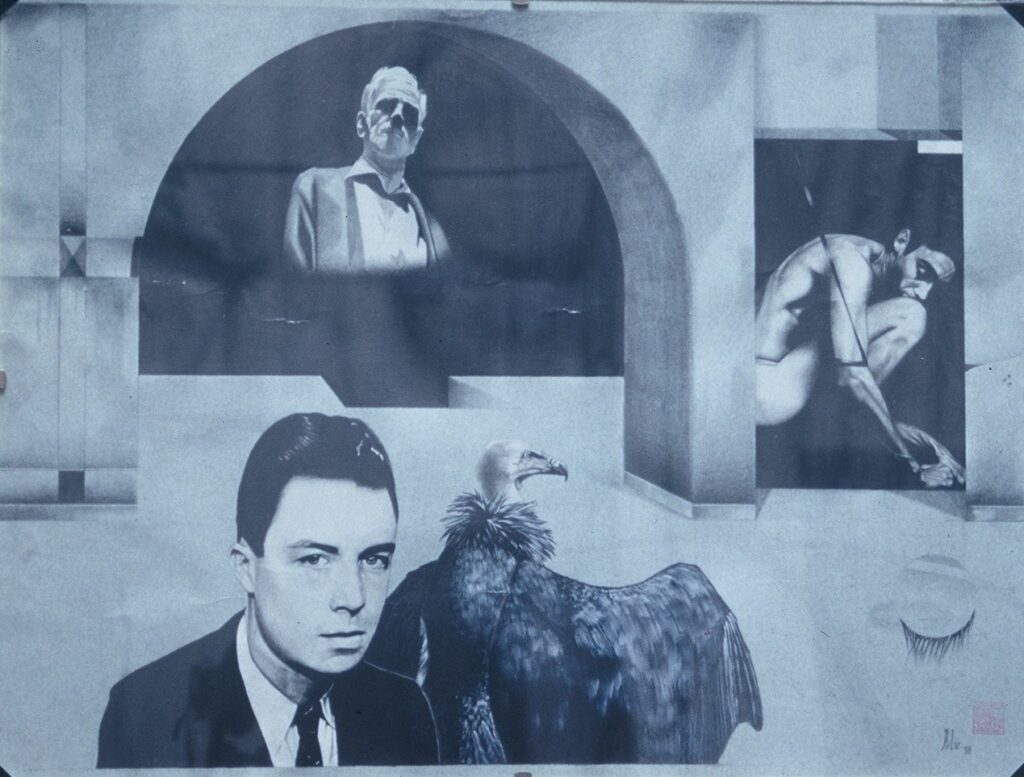

Albert Camus

Manifesto for Sad People

Edward Dutton Enjoys the Definitive Application of Absurdism

Adventures in Stationery: A Journey through Your Pencil Case, James Ward, 2014, Profile Books, Hardback, 280pp.

The philosophical school known as Absurdism developed from the belief that life has no ultimate meaning and, as such, life itself is absurd. Existentialist philosophers argued that we could cope with the absurdity of existence by finding beauty and stimulation in the insignificant and unimportant. This kind of self-created meaning could give the post-religious Man something to strive for; something to take his mind off the insanity of struggling against the Void. With no ‘hope,’ for Albert Camus insists that ‘hope’ is simply a way of avoiding confronting the absurdity of life, one must live every moment to the full. One must look for the positive in everyday things; in boring things.

Investing meaning specifically in ‘boring’ things, however, was never actually articulated by the likes of Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard or Nobel-prize winning Algerian-French novelist Albert Camus. This has been left to their successor, James Ward; a 33 year-old office worker from Worcester Park, a nondescript conurbation which straddles the south-west London-Surrey border and was home to John Major as a baby. For many years, Ward has kept a witty and original blog called I Like Boring Things.

It documents his attempts to find meaning in an overtly dull life – such as by cataloguing the price of Cadbury’s Twirls at every Newsagent in London – and his observations about quotidian details on his daily commute. Three years ago, this, and the cancellation of the once regular Interesting conference, led to Ward establishing the annual Boring conference. Fellow fans of the mundane gathered to give presentations on the workings of ice cream vans, their records of every sneeze they’ve ever engaged in, or their obsession with hand-driers. The quirky event garners huge media attention, even being reported in the Wall Street Journal.

Ward’s particular fixation is stationery and he has even founded a ‘Stationery Club,’ modelled on a book-club. The ultimate product of Ward’s situationist activities has been his first book, Adventures in Stationery. Written in a dryly humorous and often highly personal style, Ward explains that he had always been attracted to the stationery shop Fowlers in Worcester Park. It was, and remains, a veritable Aladdin’s cave of stationery treasures, many of them gathering dust for decades at the backs of the shelves. One day he purchased a Velos 1377 Revolving Desk Tidy and began to seriously contemplate the history of stationery. How did pencils and paper clips develop into their current form? Who invented the stapler, the ball point pen, or the post-it note? The items are so central to lives of most people – who work in excruciatingly dull office jobs – that, as Ward documents, they often take office staplers with them when they leave, having somehow bonded with them. Who were the stationery obsessives who developed and manufactured these items? Clearly obsessive himself, and reflecting considerable research and attention to detail, Adventures in Stationery establishes all of this.

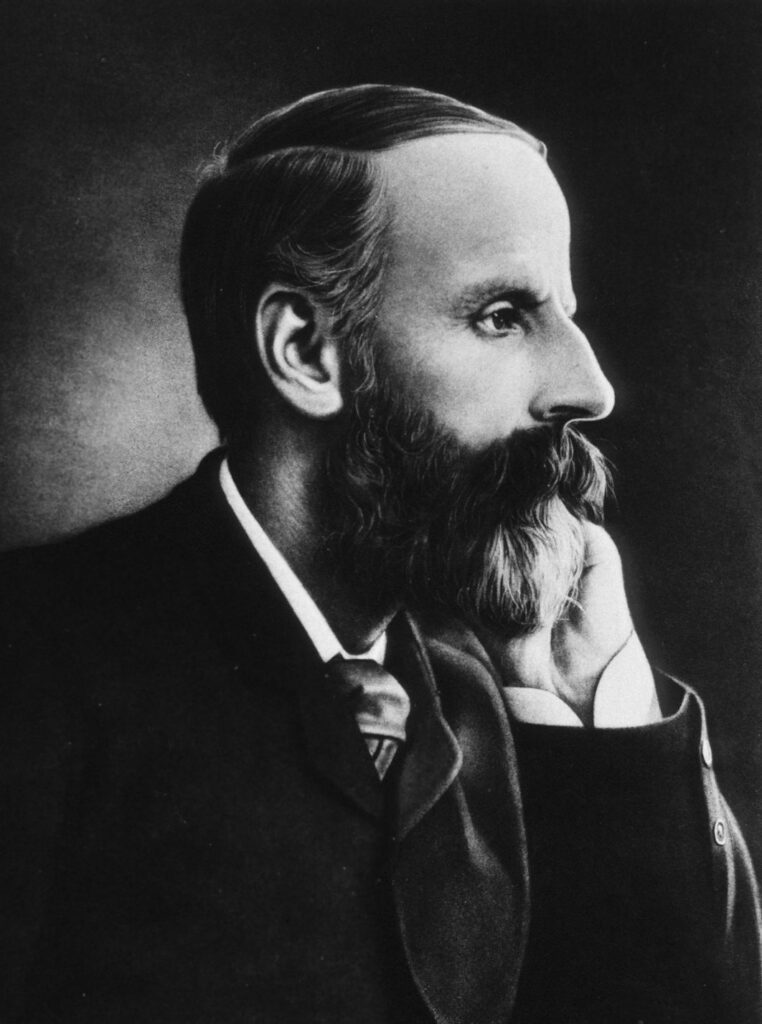

James Ward, 1843-1925

One of the strongest points of this book is just how many functions it serves. It is a meticulously researched history of the development of different items of stationery, quoting from relevant primary sources, such as old newspapers and even the original patents for different versions of the paper clip (though, alas, there is no citation list at the end). Ward thoroughly examines why certain items of stationery developed at certain times: the Industrial Revolution leads to more records, more paper, and the need to hold it together somehow. The trains lead to more travel and the rise of the postcard . . .

It is also a clearly explained introduction to the science of stationery. It looks in fascinating depth, for example, at the numerous tiny changes that stationery pioneers had to make to ensure their products worked and the incredulity with which their new ideas were sometimes greeted. One of the most intriguing cases is the Hungarian racing enthusiast Laszlo Biro, the inventor of the biro. He and his brother needed to invent, ‘an ink that remains fluid in the cartridge but dries as soon as it touches paper.’ They were told in no uncertain terms by a chemistry professor that ‘there are two kinds of dye . . . those that dry quickly and those that dry fast. What in heavens name do you mean by a dye that makes up its own mind when it should dry fast and when it shouldn’t? It does not and cannot exist.’ Of course, the two Biros were adamant they would prove him wrong. And as geniuses of the stationery world, they are two of many eccentric, inspired inventors and promoters whose lives Ward lovingly recreates. Laszlo Biro, for example, became such a successful hypnotist that he dropped out of university. He drifted between different jobs – always innovating something while there – before being inspired to invent the ball-point pen while watching children playing marbles in 1936.

Buttered with wry pop references, amusing personal asides, and stationery-related anecdotes – including the lethal nature of early erasers – the book also works as a piece of escapist comedy. Ward’s surreal humour is encapsulated in his introduction to the chapter on glue: “‘I’m sticking with you, cos I’m made out of glue’ sang Moe Tucker . . . in 1969. It’s a nice sentiment but one which makes little sense . . . If anything, the use of the word ‘with’ instead of ‘to’ implies that I’m the one made out of glue. I am not made out of glue.’ Comedy often involves original connections and Ward is clearly adept at this, noting that pencil cases are less popular in the USA because everyone has lockers or that stationery will live on, in a computer world, in computer icons and in a formalized form. The book is also comfortingly nostalgic because, as Ward points out, it is our time at school that is, or was, dominated by stationery. As such, August, rather than Christmas, makes or breaks stationers.

But this book is at its best when Ward draws upon his personal stationery adventures and experiences. These include applying, unsuccessfully, for over 30 jobs at Argos in order to discover the ‘trade secret’ of how many of their pens go missing each year, attempting to explain to school friends that – for good scientific reasons – a shatter proof Helix ruler is not ‘snap-proof,’ and his months of correspondence with ‘Michelle’ (from Blu-Tack manufacturers Bostik) in order to discover precisely what are the ‘1000s of uses’ Blu-Tack claims it is capable of. She eventually sends him a list of 250 different uses, having consulted colleagues around the world. And as the correspondence concluded: ‘(Michelle) sent me a free pack of Blu-Tack which I put in my desk drawer for safe-keeping. I will never open it. It’s a special memento of my correspondence with Michelle. That is one use for Blu-Tack that doesn’t appear on any list.’

In fact, this book would have been even better if Ward had taken us on even more of his own personal stationery adventures. We have hints that a dull-working life – he has been a librarian and did technical drawing at university – may have caused the flames of his childhood fascination to burn even brighter. Any future book should further develop this persona – inspiring, comical and tragically absurd – of the psychologically unconventional figure with the seemingly humdrum existence on a personal crusade to understand the superficially ordinary. This is a very impressive first book. If you’re not interested in stationery at the start of it, you certainly will be by the end.

Dr. Edward Dutton’s latest book Religion and Intelligence is published by the Ulster Institute for Social Research