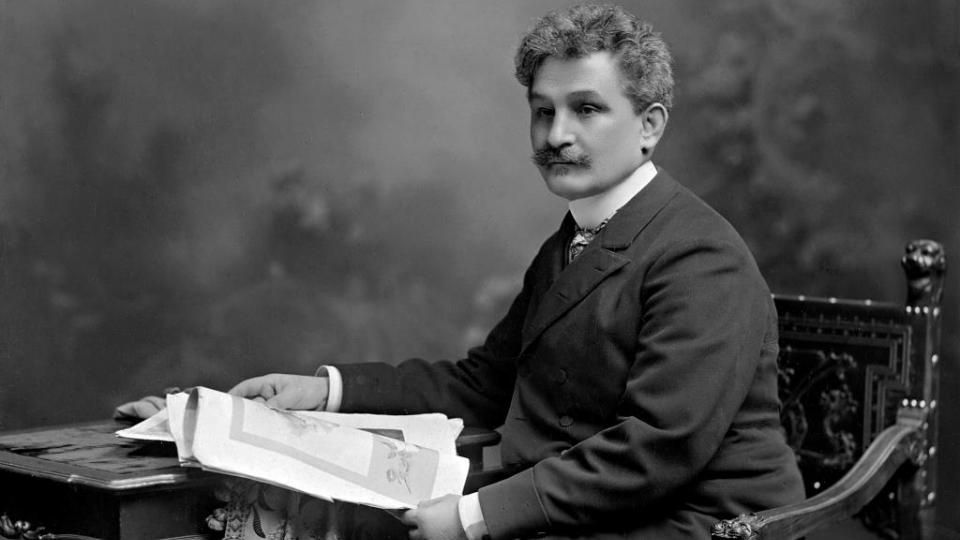

Leoš Janáček

Kát’a Kabanová

Opera in three acts; music by Leoš Janáček, libretto by Leoš Janáček based on a Czech translation of Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky’s play The Thunderstorm, orchestra conducted by Edward Gardner, direction by Richard Jones, Royal Opera, Monday 4th February 2019, reviewed by Leslie Jones

All of the characters in Kát’a Kabanová, with the exception of the carefree, courting couple Varvara and Kudrjáš, are, in Dylan’s words, “bent out of shape by society’s pliers”. They are either inauthentic and hypocritical, like Dikoj and Kabanicha, or conflicted and tormented, like Kát’a and Boris. And most of the men are weak and compliant, especially Tichon Kabanov, who is dominated by his mother, and Boris, who is financially dependent on his uncle Dikoj and who tamely accepts the latter’s instructions to depart for Siberia.

Kát’a herself is a complex, child-like individual, who has visionary experiences and hears voices. In Act one, she confides to Varvara that her mother treated her like a doll, yet that she was then “free as a bird”. But married life has made her wither. With her dreams of flying, her ineffectual struggle to deny her sexuality and her tendency to project inner urges onto external agencies such as fate, Kát’a is a case study. As Christopher Wintle observes, “The tragedy of Kát’a is that she instinctively shares the oppressive moral values of the community to which she is bound…” (What Opera Means). She claims to love her verbally abusive and controlling mother-in-law, “You are like a mother to me”, she submissively informs her. There is no escape, then, from the super ego, the repressive representative of society in your head.

The demanding role of Kát’a was performed by American soprano Amanda Majeski – majestic indeed. At times, her powerful voice has a harsh quality. But she is adept at capturing this character’s emotional lability, impulsivity and vulnerability. Her body language, including her various postures and hand movements, were particularly expressive. Her final meeting with Boris, when she hangs pitifully round his neck, was unbearably sad. Indeed, some will find her depiction of a disintegrating personality too near the bone.

In director Richard Jones’s new production, Ostrovsky’s storyline is transposed from 19th century Russia to the Soviet Union of the 1970’s, as indicated by the hairstyles, the cars and the unfashionable clothing, notably Kudrjáš’ jersey. (Note, however, that music critic Michael White reports that similar attire can still be seen in Brno!) Janáček himself, like his hapless heroine, had an unhappy marriage. He and his wife Zdebka lost two children but he eventually found solace with a younger woman, his muse Kamila Stösslová. In Kát’a Kabanová, he uses music to depict both effects in nature (the river, the storm) and feelings (anxiety, exultation, despair).

The sets, designed by Richard Jones and Antony McDonald, take minimalism to a hitherto unexplored level. At the opera’s conclusion, the stage, so recently lit up by strobe lighting during the thunder storm, suddenly turns pitch black. We were reminded of the unforgettable finis to The Sopranos.

Death of Kát’a