“It’s the rich what gets the pleasure …”

Robert Henderson reviews Russell Brand’s rant

The Emperor’s New Clothes (2015)

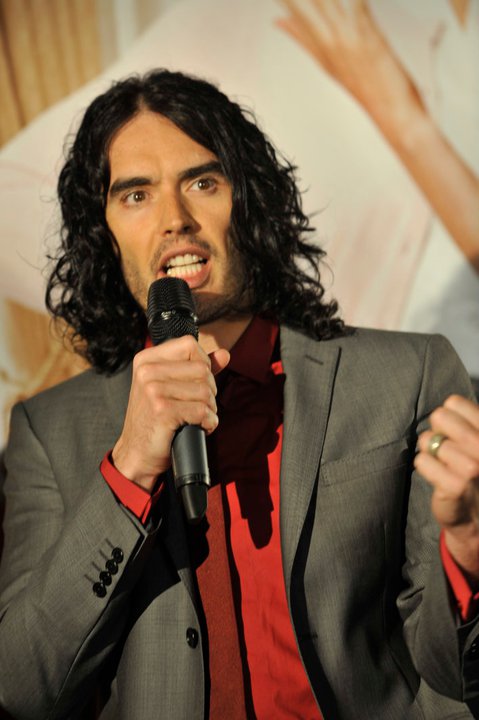

Narrator: Russell Brand

Director: Michael Winterbottom

This documentary shamelessly mimics Michael Moore with a large dollop of “The smartest guys in the room” thrown in for good measure. The end product is a tepid imitation of Moore’s style and a rather better pastiche of The smartest guys in the room.

Like a Moore documentary there is much in the film which is shocking: the greed and irresponsibility of the bankers: the overt or tacit collusion of politicians which allowed bankers to be effectively unregulated in the run up to the 2008 crash; the failure to punish with the criminal law any of those who were responsible for the banking crash; the ability of the likes of Fred Goodwin (the erstwhile CEO of the Royal Bank of Scotland) to walk away with a pension worth hundreds of thousands a year after wrecking, through his megalomania for expansion, one of the largest banks in the world. More generally the film also makes much of the growing inequality in Britain.

Sounds intriguing? But the problem is Brand, unlike Moore, never manages to get to quiz any of those responsible or even to embarrass them by getting close enough to shout questions at them. This is in large part simply a consequence of Brand /Winterbottom choosing a subject – bankers’ recklessness – where getting to speak to the culprits was an obvious non-starter. But that makes a large part of the film’s approach an anticipatable and hence avoidable mistake.

A fair bit of the film features Brand arriving at the head of office of, say, a high street bank, daringly entering the public foyer and then hitting a brick wall of indifference as he is left to grill receptionists and security guards on the wickedness of their employers. The result is underwhelming the first time he uses the ploy, but moves from underwhelming to irritating as the device is repeated several times. The nadir of this “beard them in their lairs” tactic is Brand’s arrival at the home of Lord Rothermere (whose family own amongst other publications the Daily Mail) to tackle Rothermere about his non-dom status. After Brand had vaulted over a wall to show his rebel devil-may-care tendencies, the scene ended with him conducting a meaningless conversation with a bemused housekeeper via an answer phone. There was a vapidity about all these scenes which robbed them of their potentially humorous situational content based on the incongruity of what Brand was asking rank and file employees. In the end it was simply Brand behaving boorishly.

All of this tedious, ineffective and self-regarding guff is wrapped within an ongoing theme of Brand “going back to his roots” to his childhood town of in Grays in Essex. (Brand is part of what Jerome K Jerome called “Greater Cockneydom”). He is certainly much friendlier in his dealing with the white working class than the vast majority of those on the Left these days who tend to approach them with all the delight of someone trying to avoid dog excrement on a pavement, but there is a cloying quality to his relationship with those he meets as though he is playing in a rather ham fashion the part of a cockney sparrow returning to its long deserted nest. He is also rather too keen to prove his street cred- there is an especially cringeworthy episode where Brand vaults a underground barrier and claims he has dodged the fare. More damagingly perhaps, was that hanging over his words on the state of the have-nots and the misbehaviour of the haves hung the fact that Brand is a rich man, a fact he tried to address by trying to make a very feeble joke indeed about the fact.

Ironically Brand displays a strong conservatism with a small ‘c’ when he laments the change from the Grays of his youth as a place where the shops were run by local people and “all the money spent in the town stayed in the town” to a modern Grays of boarded up shops and multinationals who suck the money and by implication the sense of community out of the place.

That is too black and white a view of then and now, but I can sympathise with Brand’s general nostalgia for the not so distant past. My memory tells me that people were generally more content forty years ago. The trouble is that Brand completely fails to address the thing which has most dramatically changed places such as Grays namely, mass immigration, which of course is all part of the globalist ideology he purports to loathe. That he should avoid the immigration issue is unsurprising because it is part of the credo of the modern Left that it is nothing but an unalloyed boon, but it does undermine horribly the credibility of the film as an honest representation of reality.

The most nauseating part of the film involved Brand using an audience of primary school children (at his old school) to get his message across by feeding them with the most intrusive sort of leading questions along the lines of “Bankers earn zillions of pounds a year while the person who cleans their boardroom takes home fifty quid a week: is that fair?” The children were charming, but using children as ideological props is a cheap shot at best and abusive at worst.

The film is at its best when Brand is working from a script with crisp graphics and commentary in the style of The smartest guys in the room. The cataloguing of the excesses of the financial industry and the stubborn refusal of the authorities in Britain to bring criminal charges against any board member of the institutions which were responsible, even the banks which required bailing out by the taxpayer, was angering. Comparing this escape from punishment by high ranking bankers (who invariably left loaded with huge amounts of money on their departure from the offending banks) with the many, often quite severe, custodial sentences handed out to the 2011 rioters for stealing items worth at most a few hundred pounds and often for much less showed a reality that lived up unhesitatingly to the old refrain “It’s the same the whole world over, It’s the poor what gets the blame, It’s the rich what gets the pleasure, Ain’t it all a bleeding shame”.

There is also some strong stuff about the growing inequality in Britain and the thing which with frightening speed is creating a massive generational divided, namely, the grotesque cost of housing which has removed from most of this generation any chance of buying a property and forcing people increasingly into extremely expensive private rented accommodation. But here again, the immigration issue was left untouched.

The film missed several important ricks. One of the scandals about the way bankers have been able to walk away from the 2008 crash without any serious action being taken against them is that there has been no attempt to apply the provisions in the Companies Act relating to directors behaviour. These provisions allow the removal of personal limited liability from directors where they have behaved in a reckless fashion. Remove their limited liability and creditors, including the government on behalf of taxpayers, could seek every penny they hold.

Then there is the extraordinary fact that the shareholders of the bailed out banks still hold shares worth something. The banks were irredeemably insolvent when the Labour government bailed them out. The shareholders should have lost everything. This fact went unexamined.

But the film’s greatest failure is to spend far too little time role that politicians played in the economic disaster through their lack of regulation and the aftermath of the 2008 crash. For example, there was nothing on the Lloyds TSB’s takeover of the HBOS which ended up capsizing Lloyds. This takeover was done at the behest of Gordon Brown and turned Lloyds TSB from a solvent bank with a reputation for prudence and caution into a bank which had to be bailed out by the British taxpayer. The bank is now the subject of a civil action by disgruntled shareholders who claim they were misled by Lloyds about the state of HBOS.

Much of what Brand dislikes I also dislike. Like him I deplore globalisation because it is destabilising at best and dissolves a society at worst; like him I think it a monumental scandal that neither the main actors in the financial crash nor the politicians who had left the financial services industry so poorly regulated were ever brought to book; like him I am dismayed at the growing inequality in Britain and the particular disaster that is the ever worsening British housing shortage. But the film offers no coherent or remotely practical solution to the ills of the age. It is simply a rage against the machine and like all such rages ultimately leaves its audience dissatisfied after the initial adrenal surge of sympathetic anger.

ROBERT HENDERSON is QR’s film critic

Is “Brand” actually human? He looks and sounds like an AI synth manufactured in some lab deep beneath “The Guardian” offices, but which has somehow got out of control.