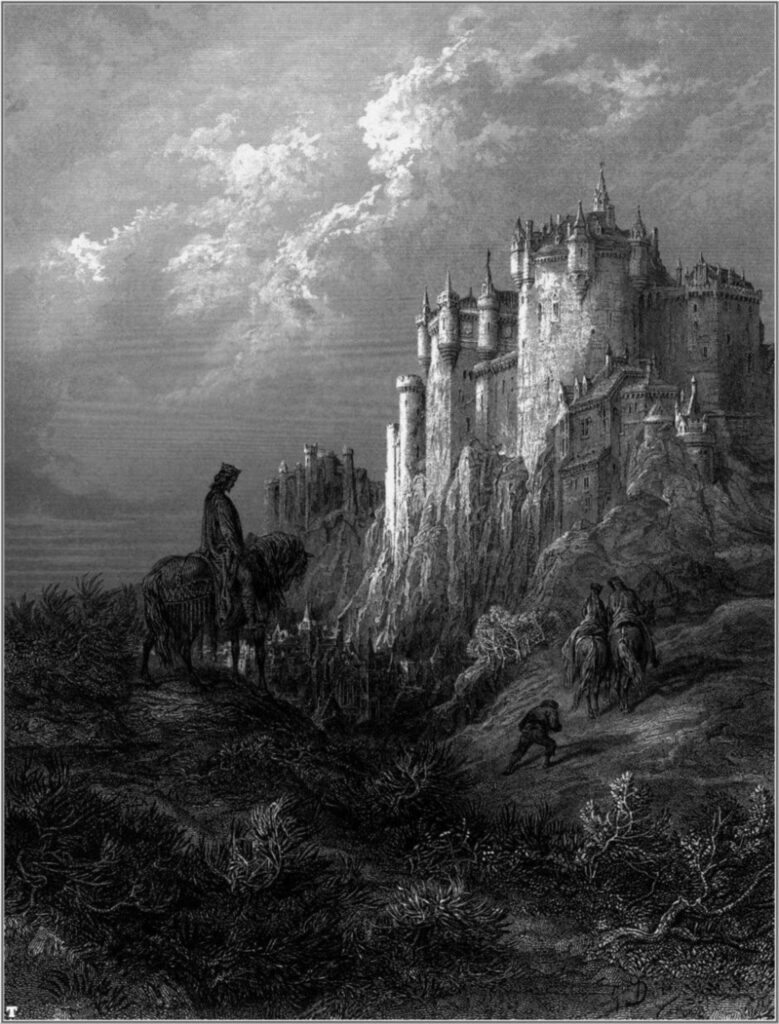

Camelot, Gustave Doré’s illustration for Tennyson’s Idylls of the King

Endnotes, September 2022

In this edition: the Celtic musical world of Arnold Bax, by Stuart Millson

In 1917, the nature- and myth-worshipping English composer Arnold Bax travelled to the northerly Cornish coast, to the “castle-crowned cliffs of Tintagel”, for a holiday (romantic, in both senses of the term) with his mistress and fellow-musician, Harriet Cohen. From this visit was born one of the most striking tone-poems in the history of the English musical renaissance: a work of about a quarter-of-an-hour in length, which contains some of the most powerful passages ever penned by a composer of this period and style.

Bax was born in the London suburb of Streatham, a place far removed from the sunshine and shadow of Eire and Kernow (the Celtic name for Cornwall). But after discovering and absorbing Irish literature and folklore, he claimed that: “The Celt within me stood revealed.” The Arthurian site of Tintagel was a major point of fascination for this Celtic-like wanderer of the imagination; Bax linking his own passionate affair with Harriet to the legends of King Mark and Tristan and Isolde. And so, on “a sunny, but not windless summer’s day”, he envisaged in musical form the sea-drift of the Atlantic lulling the onlooker into a reverie of ancient, mythical times. The heady, yet tightly-argued symphonic poem, Tintagel, came into being: a brilliantly-condensed, high-romantic musical drama; a piece that evokes high-tides, remote seabird-sounds and the clash of arms of ancient British warriors. The piece was recently performed at the Proms by the Sinfonia of London, conducted by John Wilson – a musician known, principally, for his immaculate staging of Hollywood musicals, but now forging a reputation as a champion of early-20th-century British works.

Yet there is more to Bax’s Celtic world than Tintagel, monumental though that is. There is also a longer symphonic poem, The Garden of Fand. This is the story of a small craft, heading for Eire’s shores in a fair breeze, but which becomes caught by a huge wave and brought onto a mysterious island, the realm of Fand, the daughter of the god of the sea. Here on this magic place there is feasting and dancing, but (as in Tintagel) a sense of tumult and wild imagination envelopes the scene: the Celtic ocean serving as the stage to the drama. The conductor Vernon Handley, who conducted a pioneering recording of Bax’s Fourth Symphony in the 1960s with the Guildford Philharmonic, loved and championed The Garden of Fand and recorded this much-neglected work (on the Chandos label) with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The conductor even named his daughter, Fand.

Celtic legends and the stories of a wild, early Britain informs Bax’s music: notably, Northern Ballads, for orchestra; the magical world of a Happy Forest; the mist and emptiness of winter-time, November Woods; and, of course, seven remarkable symphonies (the most sunlit being the Fourth), which prompted the Finnish composer, Jean Sibelius, to remark, “Bax is my son in music”. A gripping sense of a new year coming to life is to be enjoyed in another masterpiece, Spring Fire – a British ‘Rite of Spring’, with an opening much like the opulent forest murmurs at the beginning of Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder. The BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Norman Del Mar, revived Spring Fire in 1983, launching their autumn and winter season at the Royal Festival Hall with the work – yet sadly, the BBC paid little attention to Bax thereafter. However, both the Lyrita, Chandos and Naxos record labels have given us superb Bax cycles.

When not composing music, Bax also wrote under a Dublin-sounding pseudonym, Dermot O’Byrne, and despite being a Master of the King’s Musick (an honorary, ceremonial court title) he sympathised with the notion of Irish independence, although this was more romantic and historical than viscerally political. The Celt within him stood revealed once again. And when we hear the music of this early-20th-century master, that bygone Celtic world beckons to us again.

Stuart Millson is the Classical Music Editor of The Quarterly Review

Interesting to see a comprehensive study of all the musical Arthuriana. We await a new composition about the Promised Return of our National Saviour, but not if the chief role is written specifically for a Disabled Black Lesbian Muslim.

Richard Barber edited “King Arthur in Music” (Brewer 2002). A fresh edition is perhaps needed. Arthur continues an endless source of ideas of all kinds. He embodies the heroic archetype of western civilization, embodying features listed most notably by Lord Raglan. The “original” was probably a warrior chiefly operative along the western Hadrian’s Wall where the earliest sites of Camlann and Avalon are identifiable.