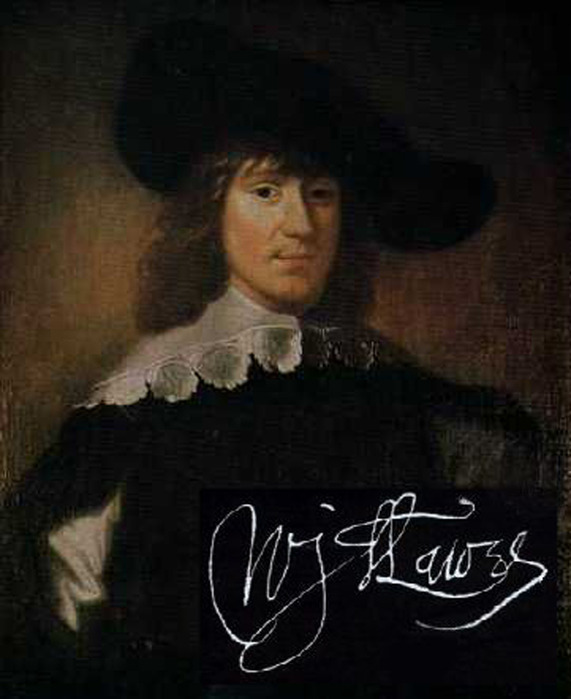

Thomas Tomkins Copyright City of London Corporation / Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

ENDNOTES

A sad pavan for these distracted times

STUART MILLSON remembers two overlooked English Civil War composers

The period of the English Civil War was a time of profound anxiety for the country. The breakdown of authority and civil order was accompanied by an emotional, even psychological anguish: premonitions of mortal disaster, visions of giant fish in the Thames, rumours of witches and familiars, and the rise of the self-appointed witchfinders and other puritan fanatics. Cannon fire and muskets in city streets, English fields running red with blood, and churches wrecked by those who saw music, or a statue, as evidence of Satan: these were truly distracted times.

Yet despite living in a wasteland of war and religious psychosis, England still seemed capable of producing magnificent music, and we must never forget that some 250 years before the famous “English musical renascence” of Parry, Elgar and Vaughan Williams, our country had composers of the calibre of Thomas Tomkins and William Lawes. Both Royalists, Tomkins and Lawes succeeded in producing a body of work which stands, to my mind, as some of the finest music ever to have come from these islands. Purcell, of course, is credited as the greatest composer of the 17th century. But Tomkins and Lawes are names which deserve to be seen alongside the great composer of funeral odes, The Fairy Queen and King Arthur.

Thomas Tomkins was born in Pembrokeshire in 1572, in the tiny cathedral city of St. Davids. He followed his father’s calling into the world of church music, Mr. Tomkins senior holding the position of Master of the Choristers, and vicar-choral. But the family migrated to Gloucester, and by the mid-1590s, the young Thomas had gravitated to the role of instructor of the choristers at Worcester Cathedral. He was to become an important member of the Chapel Royal (appointed organist in 1621 – Orlando Gibbons was the senior organist); and was responsible for the musical planning for the coronation of King Charles I. In his declining years, Tomkins lived with his son, Nathaniel, who was to continue the family’s musical name. The tide of war may have temporarily suppressed the English voice in music, but it can be said with certainty that it was Tomkins’s example and dedication (and indeed, that of his son) which ensured the survival and revival of the radiant spirit of our anthems and choral services.

The nobility of the music which he produced sings across the centuries; its Englishness and church setting, indissoluble and inter-linked elements of its character. It is tempting to think of Tomkins, whose times seem now so remote and ancient, as a harbinger of the spirit which led to the emergence of Edward Elgar: a link across time and space to the churches and cathedrals of Gloucester, Worcester and Hereford of the 1890s and 1900s. How curious that English music should find its parent-stem in this region marked out by the River Severn and the Malvern Hills. The mysteries of the English church tradition find full realisation in Tomkins’ Great and Marvellous are thy works, with such lines:

“Lord God almighty;

just and true are they ways, thou king of saints,

Who shall not fear thee, O Lord,

and glorify thy name?”

The line… and glorify thy name… is repeated, the repetition acting as an affirmation and an echo; a perfect piece for a church service, and a most important treasure in Musica Deo Sacra, the great Tomkins collection, published after his death. Yet this man, whose life was ruled by the church calendar, can also be seen as a composer capable of capturing the tumult of his era; fulfilling a role that only became officially understood or “appointed” in modern times. Just as Elgar commemorated the passing of a king, and an age, in his great Second Symphony of 1911 (the slow movement, a magnificent lamentation for the passing of Edward Vll, but also, perhaps, a clairvoyant mourning for the England that would sink into the mud of Flanders and the Somme), so, too, was Tomkins a musician who reflected wider national feelings. His three-minute A Sad Pavan for these distracted times tells of England’s misery, as Charles l awaited execution in the bitter winter of the New Year, 1649. The manuscript of this work (and one can only imagine the pain with which the composer inscribed his feelings onto paper) dates from the February of that year.

Tomkins, like so many of our native composers, was also inspired by a vision of bucolic life. In a recording from just over 40 years ago by the Purcell Consort of Voices conducted by Grayston Burgess, Early Music enthusiasts found this quintessential composer of church anthems bidding farewell to urban life and rejoicing in a scene in which “winter is going and trees are springing”: Adieu, ye city-prisoning towers – a spirited part of an old English compendium (alongside the sporting country lads and country nymphs as seen or imagined by Michael East, Thomas Campion and Giles Farnaby!) And in his last years, Tomkins did in fact forsake the life of the town: abandoning the environs of Worcester Cathedral (his home and belongings badly damaged during the siege of the city) for the village of Martin Hussingtree, not far from Droitwich Spa, where he died in 1656.

William Lawes

His fellow Royalist composer, the young and brilliantly gifted William Lawes (Henry Lawes’ younger brother) met his end in 1645 in combat during the siege of Chester. His loss at the age of just 43 affected King Charles very deeply… “Hearing of the death of his dear servant, William Lawes, he had a particular mourning for him when dead, whom he loved when living, and commonly called the Father of Musick.” He was undoubtedly a man of action and resolution, sacrificing himself to a noble cause, yet not a professional soldier: “…betrayed by his own adventureness.” (Thomas Fuller)

A pupil of John Coprario, Lawes was a prolific composer of fantasias and consort music, mainly for viols and theorbos, and his music survived him in manuscript form. A talented player of the bass viol, he was interested in the music of Monteverdi, and in 1635 became a “musician in ordinary for the lute and voices” at the court of Charles l. Denis Arnold, writing in The New Oxford Companion to Music says of Lawes:

He also wrote some attractive verse anthems and a considerable amount of music for masques, some of which shows a strong sense of large-scale organization of the kind which Purcell was to explore in his theatre music.

With clear, beautiful lines, and a great ear for atmosphere and even special effects (such as the Ecco in the Royal Consort in D Minor for two theorbos), the music of William Lawes might have become one of the great presences in our artistic life. His situation in our musical history can almost be compared to that of the composer George Butterworth, killed in the First World War, and Walter Leigh, killed in action in the Second: who can predict what these remarkable men might have achieved had they survived. Fortunately, the works of this craftsman survive, and alongside the choral glories of Tomkins tell us a story quite at odds with the notion that England (until Parry or Elgar) was the “land without music”.

STUART MILLSON is Classical Music Editor of the Quarterly Review

I am trying to find the organ sheet music for Tomkins A Sad Pavane for these distracted Tymes. Do you know who publishes it?

Felicity O’Brien