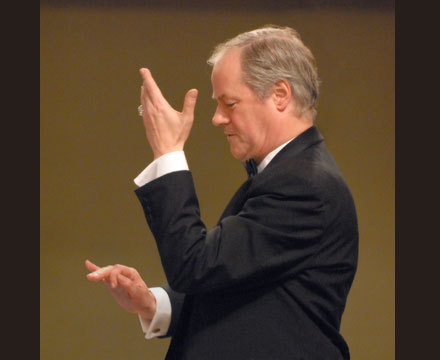

Ronald Corp, credit Wikipedia

ENDNOTES, 11th March 2016

In this edition: concert to celebrate Ronald Corp’s 65th birthday* New symphony by Belgium’s leading modernist * The music of Ginastera – from Chandos.Ronald Corp has been a motivating, inspirational force in London and indeed British music-making for at least the last 20 to 30 years. A passionate conductor of choral music, of community and young people’s choirs in particular, and founder of the New London Orchestra, the maestro has always been a great advocate of British and contemporary music. A composer as well as a conductor, he has also sought inspiration from Eastern religions and mysticism, as well as from the Anglican and Christian tradition in which he is steeped. The composer Vaughan Williams (his A Sea Symphony was the main piece in the concert to celebrate Ronald Corp’s 65th birthday) was closely associated with English church music, and there is a sense of his works being haunted by Elizabethan sacred works and hymns. Yet Vaughan Williams was an agnostic, believing generally in a spiritual dimension to life, and embracing a “Christian culture” in music, rather than an actual statement of belief. A Sea Symphony was first performed in 1910, and although sounding completely at home in a cathedral, the piece nevertheless embraced the pantheistic, ecstatic vision of the self and the soul, as stated by the poet Walt Whitman – whose words form the “libretto” to this immense hour-long drama for soloists and chorus.

From the opening brass fanfare, with the chorus uttering the famous – “Behold the sea”, it was clear that the music of the English musical renaissance is very close to Ronald Corp’s heart. With the forces of the Highgate Choral Society and the London Chorus occupying the whole of the choir stalls, and spilling into the side annexe, the conductor drew a clear, purposeful and full-voiced response that filled the famously dry-ish acoustic of the Royal Festival Hall (the sound, though, is richer the closer you are to the platform). A vision unfurled of Walt Whitman’s seascape – “the limitless, heaving breast” of the ocean, shimmering light and fluttering flags of the ships of all nations. Baritone Roderick Williams added his strong, far-projecting voice and excellent diction – acting as a sort of musical steersman – and soprano, Rebecca Evans (a famous voice from Welsh National Opera) brought further strength and clarity to a part which can sometimes be slightly overwhelmed. Her great line, close to the opening of the work, and heralded by a dramatic orchestral flourish: “Flaunt out O sea, your separate flags of nations…” elicited the all-important tingle-factor, which all great performances of the work manage to achieve: Sir Adrian Boult with the 1950s’ LPO on Decca, and more recently, Leonard Slatkin with the Philharmonia on RCA, and with the BBC Symphony Orchestra “live” at the Proms on a BBC Music Magazine CD.

However, it is the final movement of the work which – for me – achieves true greatness: a long, visionary “procession” from Walt Whitman and Vaughan Williams, of the skies above the endless horizon; of a strange “hidden prophetic intention” – and of the restless explorations of the “feverish children” – mankind – who have descended from the “gardens of Asia”, on a quest for knowledge, truth, something more – always “steering for the deep waters”. Despite what seemed a brisker-than-usual opening to the movement (I feel that it should sound more stately, more reverential), Ronald Corp (correctly) slowed down the tempo and the pace considerably from then on, achieving that extraordinary sense of journeying beyond the seascape and into the world of the imagination and the spirit – the work becoming, in the end, a symphony about us, our endless curiosity and our grappling with the idea of an infinite universe and mortality.

Seascape, Credit Wikimedia Commons

Earlier in the concert, Ronald Corp conducted his own new composition, Behold, the sea: a choral potpourri of several movements, interweaving salty sea-shanties, with more reflective ideas – such as Masefield’s famous: “I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky…” – which, interestingly, given its valedictory, memories-of-an-old-mariner overtones – was sung by the bright voices of the New London Children’s Choir. Behold, the sea would be an ideal piece for local choral societies, who would relish the swaying, hearty rhythms of “Way, Haul Away, We’ll Haul Away, Joe!”. Immediately accessible and tuneful, the work was almost like something from the era of the English Musical Renaissance, from Coleridge-Taylor – possibly – or Percy Grainger; when it was no disgrace for a composer to draw upon folk-tunes, and music from the quayside or the seashore. So did this work look back, too far? Is there a place in the brave new world for (what critics might term) “pastiche”? For me: the answer is yes, as it is refreshing and surprising to find a composer unafraid to fly in the face of what we are made to think is the only possible music for our own era.

Having nailed my colours to the romantic mast, I must now change my navigational direction completely – running up new signals, as I approach (with, I hope, an open mind) a completely different recording – another first performance, but this time by the Belgian modernist, Antwerp-based Wim Henderickx (born 1962). Here is a composer who, at first sight, is very different from Ronald Corp… or perhaps, on closer inspection, there might not be such a wide gulf between them – especially given Corp’s own interests in Eastern music. This column has enthusiastically reviewed some of the Flemish composer’s previous recordings, finding enormous stimulation in the sound-world he has created – not least in the mysterious, occasionally disturbing composition, Atlantic Wall; a piece that spotted a possible link between the remnant stone-circles of Europe’s ancient peoples, and how future generations may view the crumbling, defensive concrete bunkers and sea-facing gun-emplacements from the Second World War. Henderickx’s latest work – his new Symphony No.1 – shows no sign that the composer has lost any of his artistic vision and vigour, with a double CD recording of total commitment and orchestral brilliance given by the Royal Flemish Philharmonic Orchestra (the conducting shared across the two discs, with several other compositions, by Edo de Waart and our own, Martyn Brabbins).

Subtitled ‘At the Edge of the World’, the symphony comprises five exciting, thought-provoking and well-sculpted movements, the finale entitled, Leviathan – the second movement, a dwelling upon Melancholia. Conceived as a work which would embrace the world, and inspired by the works of the Anglo-Indian sculptor, Sir Anish Kapoor – we are met by music that comes from an Eastern as well as Western tradition, and yet – surprisingly – this seems to be Henderickx’s most “traditional” composition to date. I sensed something of Stravinsky in the symphony, and it is clear that the composer had as his aim the restatement of the idea of that “old” form: the symphony for large, conventional orchestra that, broadly, keeps to a story, or at least conveys a clear thematic development and projection of visual ideas – or common emotional feelings. (There is an amusing reminiscence in the programme notes – the composer’s children telling their father that “a real composer” must write a symphony!) A firm recommendation for one of Europe’s leading musicians – and a possible successor (albeit, with a less austere, uncompromising style) to Pierre Boulez.

Finally, the Chandos label has recently released a CD of orchestral music by the Argentinian composer, Alberto Ginastera (1916-83) – a South American version, it could be said, of Aaron Copland in the United States. Estancia – a South American ranch – is a work of great and vivid colour, an evocation of the vast grasslands and distances, ridden by the native Gaucho; the tapestry of local colour – and a sense of the energy of the country’s rural people – finely portrayed by the BBC Philharmonic under Juanjo Mena, and recorded with the usual high-definition clarity and richness by Chandos. For listeners who are familiar with Copland’s ballet, Rodeo (which combines the shades and sounds of night with more raucous dances and jollifications), Estancia provides a similar sort of window, but into the world of Latin America. The Pampeana No. 3 also appears in this collection, a rare work from the mid-1950s, and one that – again – demonstrates Ginastera’s credentials as a modern composer, but one devoted to the spirit, natural voice and atmosphere of his country.

Stuart Millson is the Classical Music Editor of The Quarterly Review.

NB The Symphony No. 1 by Wim Henderickx will be officially available from the 25th March 2016. Full details of the composer’s recordings can be found at the following website:

http://www.wimhenderickx.com/index.php?page=recordings

The Ginastera collection by Chandos has the catalogue number 10884.