False gods

FERGUS DOWNIE remembers Soviet attempts to replace Christianity with “scientific” materialism

“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. Yet his shadow still looms. Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?”

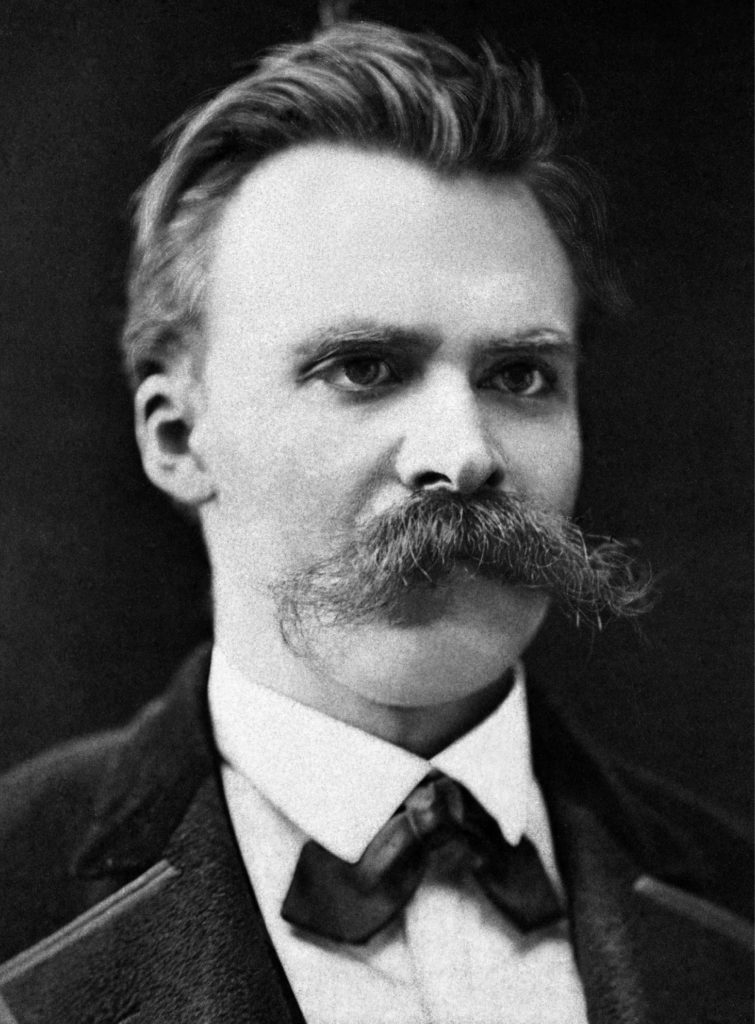

—Nietzsche, The Gay Science

Nietzsche

Communism, as the late Ernest Gellner noted, had no Vendée and scarcely any bunker to speak of. Most social orders in their darkest hour can usually call upon diehards whose faith shines brightest when others falter. This after all is one of the hallmarks of faith; the more difficult it is to maintain the more it defines the individual – but the collapsing Soviet Union could not even generate rumours of Werewolves. The 1991 counter-coup was a feeble affair and lacked the willingness to spill blood which for the Bolshevik pioneers was a signature of their faith in the Red utopia; killing on such an epic scale must surely herald something.

Thus passed the most ambitious experiment in God-building in the modern age. The origins of this peculiarly modern obsession lie in the troubled reflections of a morbid philosopher. Nietzsche was haunted by the banishment of meaning from the world, and brooded over the fate that was its inevitable corollary – a progressive disintegration of a culture which had nurtured great ambitions and select individuals. Man was the esteeming animal and whilst the objects of his reverence were in no sense true they were nonetheless precursors of great deeds. Religion had historically given men the ability to impose values on the world but now the death of God was depriving modern men of this capacity for decisive acts. It should be clear from this, that Nietzsche would have made a poor bedfellow amongst the new atheists, whose tone of infantile iconoclasm is largely absent in his work.

Despite his notorious and much misinterpreted denunciations of “slave morality”, Nietzsche never doubted that the Old Testament faith had been indispensable to an embattled nation fighting for its survival and he was not beyond some backhanded complements to the creed’s founders. Why not make a virtue of the slave morality of the weak and saddle the strong with this millstone, and how poorly did the Last Man with his jaded diffidence compare with men like Moses chiseling out a table of values by a supreme act of will? As Nietzsche noted, there were other tables of values that could have been chosen, “a thousand and one” mutters Zarathustra, but these ones created a people and gave them an inner purpose which a desiccated positivism was driving out.

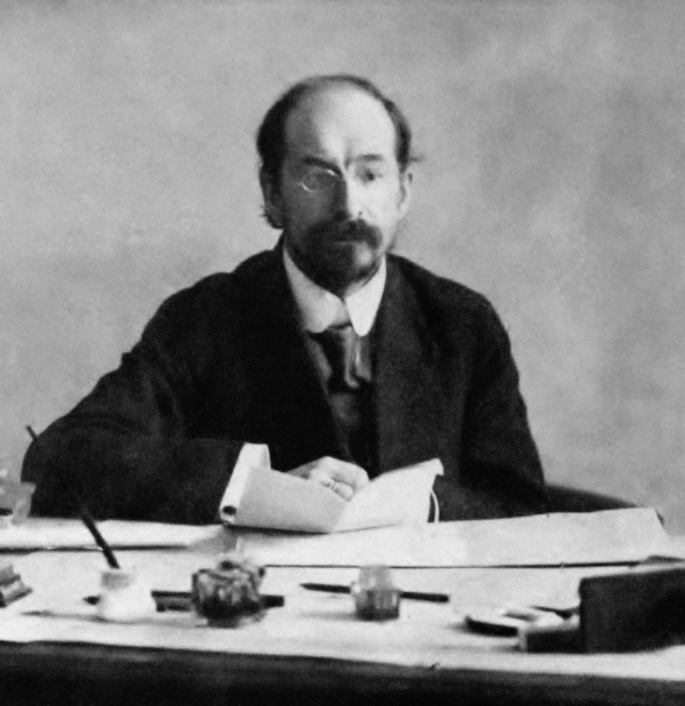

Nietzsche’s vision exercised great hold over the social sciences – Max Weber’s theory of the bureaucratization of social life is a gloomy sociological footnote to it, but its influence on avant garde artists and writers was even greater, and if for the most part they were dismissive of the metaphysics of God they were awed by the aesthetic. Religion may have been fraudulent but it was beautiful. The Bolshevik Commissar for Culture Anton Lunasharsky and the famous writer Maxim Gorky recognized this more acutely than most, and their forlorn attempt to recreate August Comte’s Religion of Humanity in the USSR was born of a recognition of Marxism-Leninism’s feeble spiritual grip.

Nietzsche anticipated such projects; the attempt to appropriate the catharsis of religion without its central beliefs was all around him. He termed this distinctly postmodern phenomenon ‘Carlylism’ after the gloomy post-Calvinist Scotsman who lost his faith and spent his life searching for another. He lost God but after the Franco-Prussian War found “the master race”. Fanatics, as Nietzsche sardonically noted, are picturesque.

The atheist attempt to create a Godless religion was a supreme example of the kind of circular false cleverness to which intellectuals are prone. Trying to resolve the tension between a transcendental deity and dialectical materialism, Lunasharsky opted to deify matter. It never quite touched the sides, and Lenin was no fan. The overt paraphernalia of God building was put on ice until the cynicism of the 60s led to a fleeting renaissance. Yet God building was always more than the half-baked secular rites of passage built into the Soviet calendar. Marxism was always a faith, and it broke precisely because it was so ambitiously totalitarian.

Anatoly Lunacharsky

The problem was noted by Gellner – human beings are not constituted for the kind of permanent spiritual mobilisation which puritan faiths require – when enthusiasm wanes they require a profane bolt hole into which they can escape. Catholicism, with all its pagan concessions, is built around this insight – but a faith which sacralises the profane – the world of material production – is bound to falter. The myth of the heroic world-historical proletariat was never likely to survive the drink-sodden cynicism of a collective farm, and when the faith of a Stakhanov wanes where does it go for nourishment?

For Lunasharsky the answer was simple and it may even have convinced him:

“You must love and deify matter above everything else, [love and deify] the corporal nature or the life of your body as the primary cause of things, as existence without a beginning or end, which has been and forever will be.”

Desperate stuff. The aim was to make men Gods but the effect was simply to drag the sublime through the dust. Faith in these circumstances tends to break rather than bend. As Goldman has noted in How Civilisations Die this may be the central contradiction of Islamism. Iran for example is experiencing the collapsing birth rates, drug addiction and pervasive anomie which heralded the Soviet Union’s collapse. Too much sacredness can make a man choke.

FERGUS DOWNIE writes from London