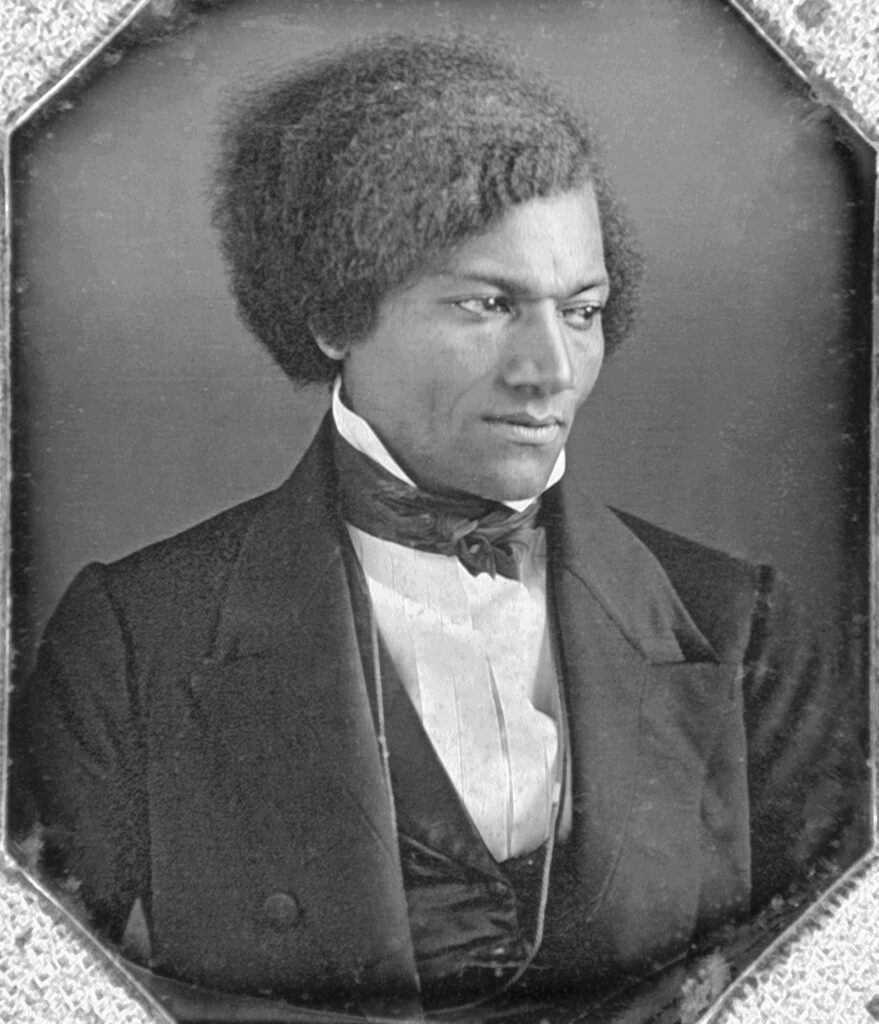

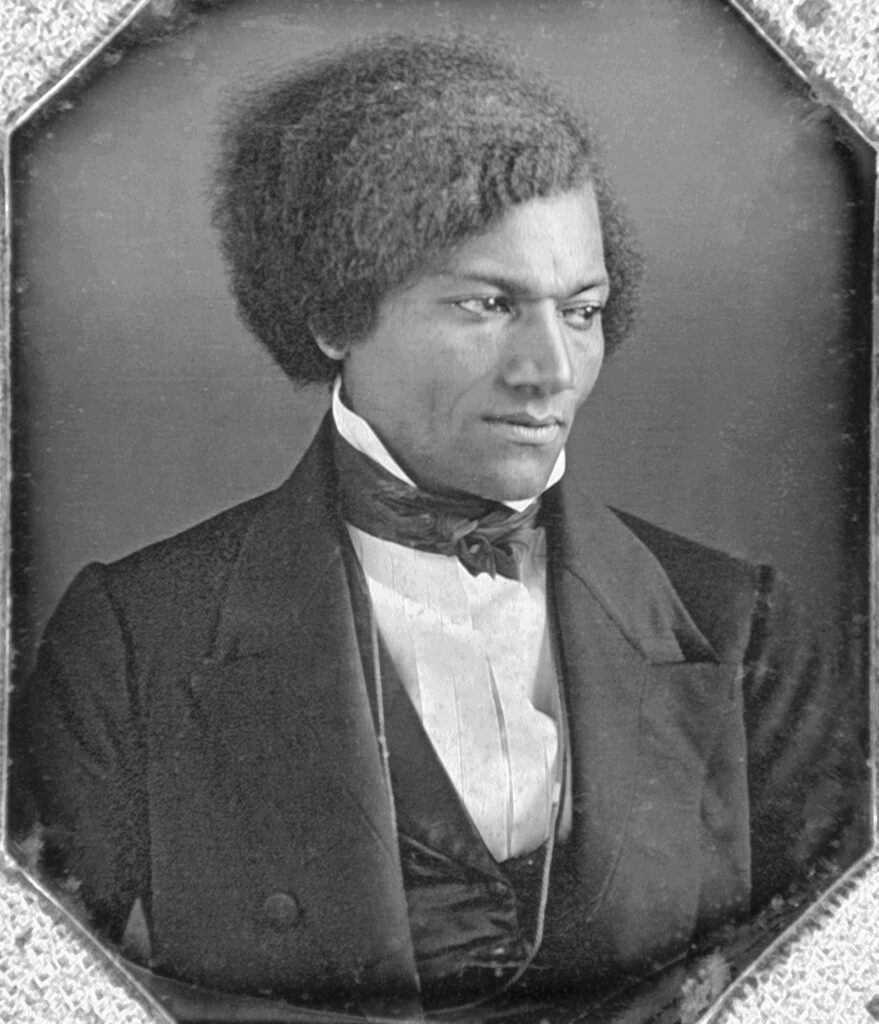

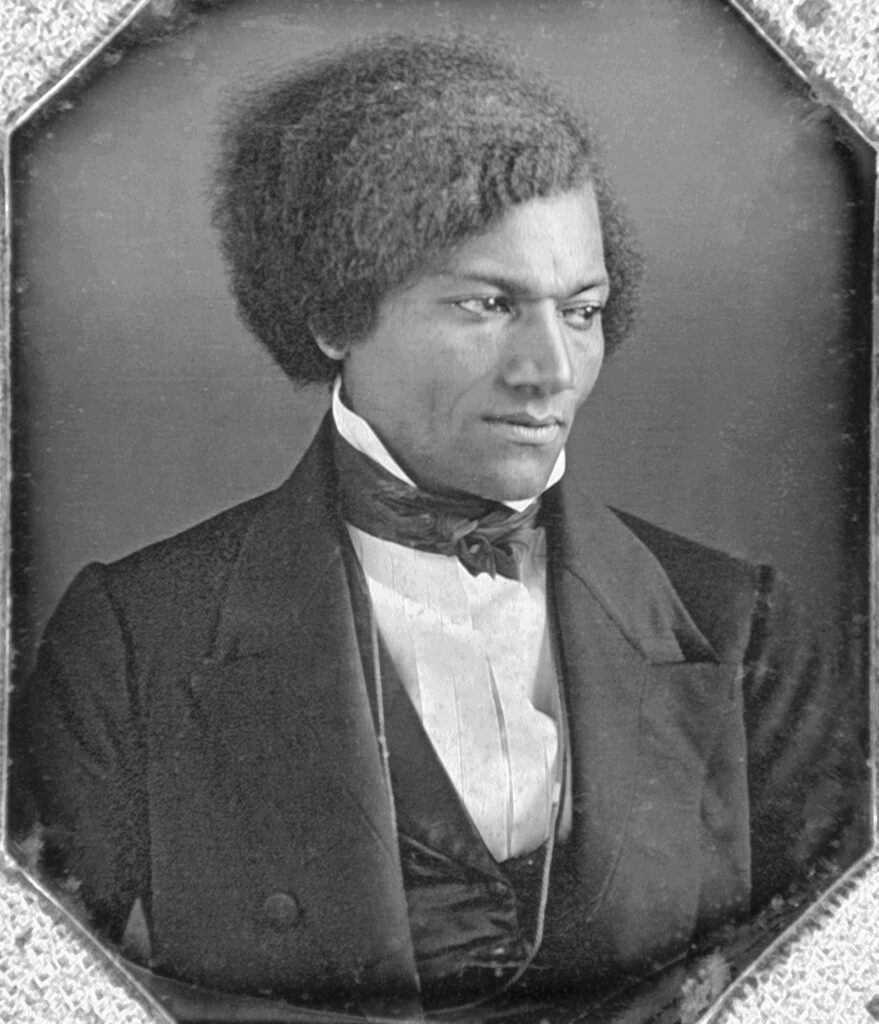

Frederick Douglass, credit Wikipedia

The Darkened Light of Faith; Race, Democracy, and Freedom in African American Political Thought, Melvin L. Rogers, Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford, 2023, 380 pp, hb, reviewed by Leslie Jones

The European is to the other races of mankind “what man is to the lower animals; – he makes them subservient to his use” (Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1835). Tocqueville despaired of ever seeing an aristocracy “…which is founded upon visible and indelible signs”, ever disappear. The habit of servitude, in his estimation, had given the slave “the thoughts and desires of a slave”. He noted that the prejudice of race was even stronger in the states which had abolished slavery, where the white “…fears lest they [the blacks] should someday be confounded together”.

Tocqueville’s pessimism about Europeans ever mixing with blacks was shared by several American commentators, notably Martin Robinson Delany. Born in 1812 in Virginia, Delany’s father was a slave, but his mother was free. Between 1850 and 1851, he was one of only four African Americans allowed to attend Harvard Medical School. He left in March 1851, never to return. The Dean, Oliver Wendell Holmes snr and many of the students had vehemently opposed the admission of black students. Professor Rogers considers Delany’s The Condition, Elevation, Emigration; and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852) a “powerful indictment of American life”. Delany espoused a theory of history in which the role of elites was pivotal. Human nature, he averred, “generally produces political and ethical hierarchies to organise human relations” (Rogers, p158).

For Delany, his dismissal from Harvard Medical School and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 underlined the unequal status of blacks in the United States, based on prevalent notions of their inborn racial inferiority. Unlike Frederick Douglass and David Walker, author of the incendiary Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829), Delany regarded the white citizens of the United States as beyond redemption. The law, as Tocqueville maintained, is an expression of the underlying ethos of the people and it made African Americans “alien to the polity” (Rogers, p119). Frederick Douglass, in contrast, believed that man “is still capable of apprehending and pursuing that which is good”. He opposed Delany’s support for an independent black state by colonisation and emigration, accusing him of spreading “hopelessness among the free colored people …and thereby…resigned to the degradation which they have been taught …must be perpetual”. According to Delany, however, Douglass obfuscated the alien status of black people. In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, dated May 1852, he confided, “I have no hopes in this country – no confidence in the American people – with a few excellent exceptions – therefore I have written as I have done”.

Could the revolutionary spirit of 1776 transform America into what the author calls “a racially just society” (page 160), or the “more perfect union” referred to by Barack Obama, in a speech in 2008? Douglass, for one, concluded his eloquent 1852 Address ‘What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?’ on a relatively positive note, stating “I do not despair of this country…I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope”.

However, “faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Hebrews 11: 1). Faith is transcendental, whereas social science endeavours to be realistic, evidential and empirical. Professor Rogers acknowledges that in the 1890’s even Douglass’s faith in democracy dimmed, as, towards the end of his life, did that of W.E.B. Du Bois. In his autobiographical work Dusk of Dawn (1940), Du Bois states that the focus of his Souls of Black Folk (1903) was “the admission of my people into the freedom of democracy”. The lynching of Sam Hose in 1899, he also informs us, disrupted his sociological work of the 1890’s, as “one could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered and starved…” “Chin up”, he urged a friend, “and fight on, but realize that American negroes can’t win”.

Melvin R. Rogers regards Donald Trump as a supporter of “white supremacy [and] nativism” (p 3). And while he generally eschews Afro-pessimism, he advises black Americans to “always look on their white counterparts with suspicion”.

“Men”, Marx contends, “make their own history, but they do not make it as they please” (The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte). We commend Professor Rogers for his indefatigable labours.

[Editorial note; many thanks to Judith Cannon for her technical prowess]

Dr Leslie Jones is the Editor of QR

Like this:

Like Loading...

The tragic history of the relationship of north American “white” people to “black” people, as slaves or free men, is as enormously complex as it is controversial. One can focus on small but significant or important topics (as in this case), and let qualified and objective specialists analyse them in what few ideologically “open” specialist journals exist.

Five prominent personalities in particular deserve balanced, truthful and comprehensive studies in this respect: Lincoln, Jefferson, Robert E. Lee, Booker Washington and W.E.B. DuBois.

I would recommend as one general survey contra mundum wokum the relevant books by my late friend Nathaniel Weyl. I hope to write on the slavery and reparations, and the so-called “replacement”, issues in 2024.

As for race-crossing (especially BxW) this again is a complicated and sensitive matter, which has escaped proper investigation into pros and any cons since the 1970s. Meanwhile, anyone specially interested can start with a search for Kenneth F. Dyer, William B. Provine, R. Ruggles Gates, Glade Whitney, S. M. Garn & Curt Stern.

Marcus Garvey was a US Negro leader strongly opposed to miscegenation. Quite gifted and energetic, he nevertheless had a pretentious and comic aspect, typically both “Black” (e.g. Father Divine) and “American” (e.g. Donald Trump). However, his Back to Africa project might have prevented much eventual trouble on both continents.