Rules for Everyone

By Bill Hartley

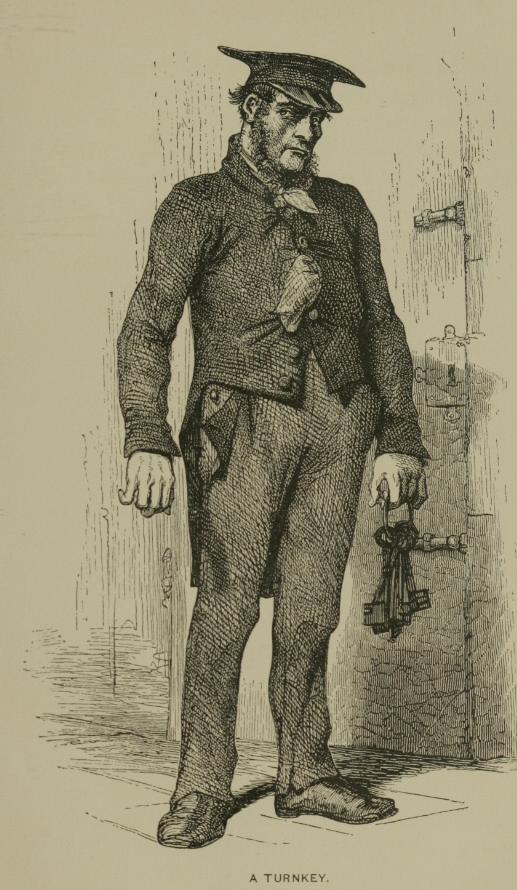

Old turnkey

Most of our larger cities still have what used to be called a local prison. Usually they date from the nineteenth century and are monuments to Victorian civic pride. Like other public buildings of that period they were meant to impress. Leeds Prison for example, is said to have taken its inspiration from Windsor Castle, though the soot blackened facade doesn’t quite match the original.

By 1877, all prisons were under the control of commissioners, whose governance was exercised by standing orders of immense detail, running to over 1000 paragraphs (plus appendices). The 1925 edition is a masterpiece of bureaucratic micromanagement, taking in every aspect of institutional life, both for prisoners and staff. Back then the prison officer was required to work a 96 hour fortnight, presumably calculated in this way to allow maximum flexibility when detailing for duty. Augmenting pay, a variety of allowances were available for various additional tasks. Perhaps the most peculiar being five shillings for assisting at an autopsy. Interestingly the usual age for retirement was 55 with no-one permitted to remain beyond the age of 60. Today’s prison staff may view this with some envy, since their union has been waging a so far unsuccessful ‘Sixty Eight Is Too Late’ campaign, against the raising of the retirement age.

Allowances followed a strict hierarchy based on rank. On transfer, for example, a governor was allowed a maximum weight of furniture of eight tons whereas at the bottom end of the scale an officer was permitted only two. Some strange additions and omissions are to be found. ‘The removal expenses of sons of officers will not be paid after they have attained the age of 18 unless such sons have become dependant on their parents by reason of mental or physical disability’. Daughters don’t seem to have been considered at all. Perhaps, because ‘in no case will the expenses of more than one domestic servant be allowed without the previous sanction of the commissioners’ and ‘The railway warrant or fare for a servant will be third class’. Surprisingly, there was no mention of which ranks might be bringing a servant with them on transfer. Married officers were required to live in quarters and even here regulations intruded. Permission to have guests ‘for a short period’ was allowed, after submitting a request in writing to the governor.

The role of the local prison remains much the same today as it was back then: holding prisoners on remand facing trial, then depending upon the length of sentence, either for the duration of their term or until transfer to a ‘convict’ prison as it used to be known. In 1925, the prison population was far smaller than today. Presumably the casualty figures from the First World War played some part in this. Liverpool prison, for example, had a capacity of 900, though the average daily roll was only 400. These days, pressure of numbers in a local prison often means containment, with little else considered achievable. As the 1925 rules show, much more was expected back then, particularly in the field of education. Simple elementary teaching was basic for young prisoners, although they ‘should not be precluded from sharing in the adult education’. Prison officers were excluded from classes, teachers being required to maintain discipline themselves. Education extended beyond the classroom. Governors and chaplains were encouraged to arrange for lectures, addresses and concerts with ‘all subjects admissible in the broadest educational sense…. to stimulate healthy interests and enlarge mental outlook’. There was though, a warning. ‘Lecturers on the British Dominions should be asked not to say anything directly calculated to encourage emigration to those countries’.

Imprisonable offences were more wide ranging than today. A court might imprison someone for failing to comply with an Order of Bastardy or for not paying maintenance to a wife. Courts were focussed on preventing feckless individuals transferring their responsibilities to the state. Ahead of release, governors had the power to allow ‘young women’ to remain in prison overnight, beyond the expiry of their sentence, ‘for the prevention of immoral purposes’, a rare example of operational experience influencing the rules. Perhaps gate staff had told a governor about the sort of person who might meet young women on release.

Most movements in and out of a local prison would have been to the courts and usually accomplished within a single working day. However, those who received longer sentences would in due course be moved to convict prisons such as Dartmoor or Parkhurst. Food would have to be provided en route. As usual, the commissioners gave this careful consideration. The dietary scale was twelve ounces of bread and five ounces of preserved meat per man.

A great deal of space in standing orders was devoted to the subject of communications. Letters written in Welsh were to be sent to the governors of either Cardiff or Swansea prisons for translation. Why they would be better equipped to deal with such letters wasn’t stated. Still on the subject of languages: ‘when a prisoner writes in German he must use the Latin character’. There seems to have been some residual hostility towards the Germans hence, perhaps, the desire to prevent possible use of the elegant Kurrent script.

Whereas today juveniles wouldn’t be allowed into a local prison, back then all ages were accepted. Considerable care was taken over their management. One of the rules is worth quoting in its entirety:

Experience has shown that much can be effected by close personal interest on the part not only of the prison authorities but of voluntary workers. The stimulus of personal touch and interest will be found far more effective than a rigid insistence on prison routine.

This runs quite contrary to everything else in the rules. Additionally staff were even required to go to the trouble of returning juveniles to their homes.

Punishments ranged from restriction of diet to loss of remission, though the rules allowed for ‘expressions of contrition’. More serious offences, such as an act of violence towards an officer, were to be referred to the courts. This could result in corporal punishment. Use of the Cat was to be undertaken ‘away from other prisoners’. The device used was carefully stipulated: ‘tails’ were to be 33 inches in length. Local prisons were also required to carry out executions. Applications for the necessary equipment were to be made to Pentonville prison. Items required were a rope, plus ‘pinioning apparatus’ and a cap. A bag containing sand weighing the same as the prisoner was also needed and the rules required that the rope be tested. ‘Care must also be taken that the condemned man does not see the grave being dug’. However he would probably have been within earshot when the rope and drop were tested. The assistant executioner was to be paid three pounds three shillings and ‘reasonable travelling expenses’ based on a third class railway fare.

The 1925 standing orders give a detailed picture of how a penal institution was to be run. The rules extended beyond the prison itself into the lives of the staff and their families. Messes and social clubs, strictly managed, were available. Evidently it wasn’t just the prisoners who lived apart from the outside world.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service