Head of Hitler by Arno Breker

Rebarbarisation

Robert Gellately, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Third Reich, Oxford University Press, New York, 2018, pp. 383, reviewed by Gregory Slysz

The number of books on the Third Reich or the Second World War could fill several libraries. So overdone has the subject become that one’s lack of excitement at the appearance of another “History” is surely excused. Anything other than the exposure of remaining epic secrets like who killed Poland’s war-time Prime Minister in exile and Commander of its Armed Forces, General Władysław Sikorski, could possibly excite. Or the delivery of a killer blow to the intriguing, yet faintly annoying conspiracy theories concerning Hitler’s whereabouts after the Third Reich’s capitulation. In the event, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Third Reich, in providing a chronological “history” across a range of selected themes, did what it said on the tin; but alas, no nuggets or killer blows.

‘A new assessment of the history of the Third Reich’, as its publisher claims, it certainly is not. Nevertheless, we are presented with a perfectly readable account of Nazi Germany from its inception to its demise. After an informative introductory overview of the topics by the editor, Robert Gellately, which is worthy of being a stand-alone essay, there is a chronological history, organised along a set on ten selected chapters, each written by experts in their field. The text is interspersed with numerous photographs, illustrations and other sources which trace Germany’s route from electoral successes, economic ‘miracles’, military triumphs to ultimate defeat at the hands of the Allies.

Professor Matthew Stibbe’s analysis of the rise of National Socialism (chapter one) enters into much detail. The points that ‘the Nazis were not the prime determinants of the circumstances in which they were able to come to power in 1933’ (p. 35) and that the content of their message was not that important, but the manner in which they presented it, especially its socialist elements (p.45), are particularly salient. In fact, the latter point, discussed in some detail by Peter Hayes’ excellent study of the Nazi economy (chapter six), is particularly apropos in today’s political climate, in which the Left prides itself on its anti-fascism. The association between mass nationalisation, both Nazi and Soviet style, and a terror regime that resists any opposition to it, should be made vigorously.

Where Stibbe lets himself down is his attempt to render ‘Catholic racist thinkers’ (p.22) complicit in the rise of the Nazis to power, given that the thinkers, like Dietrich Eckart, which he cites, were never renowned for any Catholic thinking. The attempt to link the Catholic Faith with Nazism remains an unfortunate trend in academia despite its fundamental absurdity. Elsewhere, however, Stibbe makes amends for this by asserting that Catholics were least likely to vote Nazi. That privilege, he notes, was claimed firmly by Protestants (p.46). Julia S. Torrie, in her discussion of the ‘Home Front’ (chapter 9), reinforces this disparity by making an important distinction between strongly Catholic parts of Germany where hanging and other forms of shaming were strongly disapproved of in contrast to elsewhere in the Reich (p. 288). In truth, any cohabitation between the state and the churches, be it Protestant or Catholic, was largely based on expediency, as Torrie asserts (pp.293-94). But there can be no doubt that more willing support was given to the Nazis from Protestant quarters, not only by voters but politicians, notably by the Protestant Conservative Party, the DNVP. Here, German nationalism was fundamentally entwined with Protestantism and anti-Catholicism, a notion that pre-dated Bismarck and his anti-Catholic politics.

The benefit of the doubt that some Catholic bishops may have given the Nazi regime, which Herman Beck notes in his study of ‘The Nazi seizure of Power (chapter two)’, was part of a national wave of euphoria even before Hitler became Fuhrer. Once reality set in, the church opposed Nazi policies, whenever possible, which often resulted in a halt to the most heinous crimes, like the extermination of psychiatric patients, albeit briefly, in 1941 (p.281).

Along with demonstrating the socialist nature of the Nazi economy, Professor Hayes also illustrates how, for all its inefficiencies, it allowed the state to fight its adversaries, which effectively was the entire industrialised world, for as long as it did. Despite the undoubted abilities of Albert Speer, this effort ultimately depended on the pillaging of conquered resources and on the extensive use of slave labour. From the jiggery pokery of Hitler’s Economics Minister Hjalmar Schacht and his Mefo bills and the sleight of hand of the 1930s unemployment statistics, to the ‘resevoir of compulsory loans’ stored as people’s savings with nothing to buy, Hayes lays bare the facts behind the myths of ‘economic miracles’.

Nazi economics, however, is a well-trodden path. What is less so is the theme of Hedwig Richter’s and Ralph Jessen’s chapter, ‘Elections, Plebiscites and Festivals’ (chapter 3), arguably the most interesting part of the book, if only for its revelation of the extent the Nazi Party used democratic tools to legitimise its rule. The series of elections that handed Hitler supreme power and the Anschluss plebiscite are well known but less is known of the 1936 or 1938 Reichstag elections, with votes extended even to concentration camp inmates. It is extraordinary that such a despotic regime so regularly asked the people’s approval for its actions, irrespective of the limited choices and fraud of the electoral process. What’s more, the mobilisation campaigns, involving legions of Hitler youth and other Party activists, who associated voting with national duty, surpassed those in many liberal-democratic elections. Yet, as in similar exercises in Stalin’s Soviet Union,[1] such elections were intrinsic to an elaborate ideological masterplan that sought to convince participants that they were part of a People’s Community’ or earthly paradise and which allowed the dictators behind the hoaxes to ride the horses of both tyranny and popular will simultaneously.

No authoritarian system can exist without a claim to a cultural policy to woo the masses. Alongside the jam-packed calendar of mass participatory festivals, involving every social strata of the ‘People’s Community’, was a plan to re-construct German culture, the theme of Jonathan Petropoulos’s chapter on ‘Architecture and the Arts’ (chapter 4) on the ruins of the ‘degenerate art’ that the Nazis inherited from the Weimar state (p.133).

Hitler’s Reich Chancellery

Gone would be the ‘culturally Bolshevik’ ‘politically subversive’, ‘rootless styles’ and Bauhaus abstractions, whose artists for the Nazis were ‘biologically inferior’ as they ‘could not see colours as they really were or shapes as they truly existed’ (pp. 128,131-2). There would similarly be no place in Germany for jazz, that ‘product of blacks and Jews’ or for the Jew Mendelsshon (pp. 143, 145) – why have jazz or Mendelsshon when you can have Wagner. Or for any written word that did not subscribe to the ‘blood and soil’ Manichean worldview. In their place would come a mix of classical revivalism and cold futurism so vigorously expressed in models of Linz and Albert Speer’s Greta Hall, the future centrepiece of Hitler’s fabled Germania (pp. 120,125). Obsessed with gigantomania, Hitler undoubtedly possessed an appreciation for architecture, derived from his ‘skills with brush and pen’. Had he ‘received the technical training he probably would have pursued a career as an architect; but he never passed the requisite engineering and mathematics courses’ (p.124).

David F Crew embellishes Petropoulos’s study with interesting caveats into the role of the visual arts in Nazi society whose emergence ‘coincided with the breakthrough of photography and film as mass cultural and social practices’ (chapter 5, p. 157). The records left by both avid amateur photographers in private albums as well as professionals, so vividly portrayed in the numerous news Pictorials like the Berliner Illustierte Zeitung, reveal the normal life beyond Leni Riefenstahl’s slick cinematographic productions, which themselves were central to the myth-making of the regime. The camera lens, however, could cut both ways, leaving images that propaganda spectacles and private snapshots ignored, the horrors of the fronts, the execution of enemies and traitors and above all the atrocities of the Holocaust, which Omer Bartov presents vividly in his study of the subject (chapter 7).

Leni Riefenstahl

Emboldened by hubris and the undoubted support it enjoyed from the German population, the regime embraced ever more radical ambitions which its initial military successes, largely generated by numerous Soviet blunders and minimal Allied participation, encouraged it to do. But, with the onset of Total War, accompanied by extensive Allied mobilisation, Germany’s hopeless position was fully exposed from which defeat was the only outcome. Dieter Pohl’s essay on ‘War and Empire’ (chapter 8) powerfully demonstrates that despite its conquests and plunder, the Third Reich was no match for the combined resources of the industrialised world. Its empire, Pohl notes, ‘was bound up with perpetual warfare; political stability was never achieved. Hitler wished neither to make peace nor to reach any settlement with the countries he had conquered’ (p.250). The writing was on the wall as early as the end of 1941, as Robert Gallately notes in the concluding study, ‘Decline and collapse’ (chapter 10). With ‘the Third Reich ostensibly ascending’, Gellately notes, it was already facing military crisis, on top of its serious underlying economic weaknesses compared to the combined strength of its enemies, namely the world’s three great powers’ (p314). What was incredible, as Julia S. Torrie observes, that notwithstanding official fears, civilians’ morale and the Home Front, so indispensable to the war effort, did not break down (pp.309-10).

This is not a book for seasoned readers on the Third Reich, unless reaffirmation of existing knowledge is required. What this ‘History’ does offer is an introduction to how the Nazi state came about, how it functioned, how it treated its opponents, how it was mismanaged and how it conducted the war. A single volume on such a complex topic cannot do more than skim the surface. But this does more than this. It not only covers ‘popular’ topics like the economy, the Holocaust and the seizure of power, but also topics less known to the general reader such as elections, photography, cinema and architecture. And it does so very competently. Perhaps the content could have been more adventurous in its range, given the editor’s own penchant for controversial themes.[2] It could, for instance, have broached the fascinating nature of Germany’s pre-war foreign policy relations with Eastern European states like Poland. Nevertheless, for all its limitations, this is a useful piece of kit for any student with an enquiring mind.

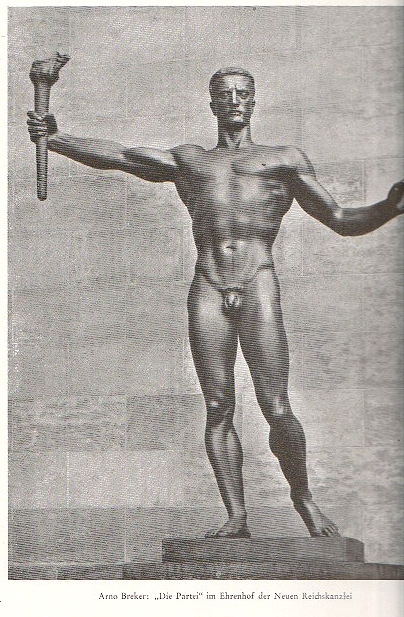

Arno Breker, Statue, Berlin 1938

Dr. GREGORY SLYSZ lectures in history. He specialises in Russian and Eastern European affairs

ENDNOTES

[1] Getty, J. Arch. “State and Society Under Stalin: Constitutions and Elections in the 1930s.” Slavic Review 50, no. 1 (1991): 18-35

[2] Robert Gellately, in Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany, 1933–1945, gives a fresh insight into the nature of German society

One noticeable aspect of recent “historiography” regarding the Third Reich is to START with the “Holocaust” and then widen the incrimination of the circle of supposed originators, collaborators, bystanders, sympathizers, non-resisters, emulators, ignorers, forgetters, minimizers, deniers, &c. The role of Catholics apparently is the latest relevant theme of yet another book on the Nazis. Apart from Karl Adam and a few WW1 RC chaplains, all patriotic anti-communists, what is there to show here? The Pelican 1940 publication on the “Persecution of the Catholic in the Third Reich” might be mentioned (pedophile priests included as well as successful euthanasia opponents). The persecution of Catholics was far worse in the USSR, Spain and Mexico, but neither Hitler nor “his Pope” can be blamed for that.

PS.

Also, “detractors”, i.e. those who mention other genocides or democides, and thereby undermine the notion of complete uniqueness. There is no getting away from Hitler’s references to Ausrottung and Vernichtung, his comments to Horthy in 1943, and Nazi propaganda like “Der ewige Jude”.

However, the huge Holocaust Centre to be erected to confront Parliament is said not only to record British “antisemitism” over the centuries (q.v. e.g. Anthony Julius, “Trials of the Diaspora”), British “racism”, and British “hostility to migrants & minorities”, warning our politicians and people not to step out of line in future over “equality, diversity & inclusion”, but also to include “some” other examples of post-WW2 genocides.

Question: will the death-toll from world-wide Marxism-Leninism be included?

The widespread hostility to the IDF operation in Gaza, aka “antisemitism”, has re-ignited demands to build the £100 million Holocaust Centre near the Parliament of Simon de Montfort, Joynson-Hicks, Ernest Bevin & Jeremy Corbyn.

Will the antisemitism of Nazi Germany and Christian England described in its education centre be accompanied therein by the attacks on Jews and Judaism by Islamists and Communists? Is sauce for the goose sauce for the gander.