Leopardi, Giacomo, (1798-1837) A Ferrazzi,Recanati, casa Leopardi

Prophet of Gloom

Zibaldone: the Notebooks of Leopardi, translated from the Italian, edited by Michael Caesar and Franco D’Intino, Penguin Books, London etc, 2013, hb, 2,052 pp

O nature, tell me, nature

Why do you never keep

Your early promises?

And why deceive

Your children with such hope?

From To Silvia, Leopardi, Canti

The illustrious poet and savant Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837) was born in Recanati, a tiny town in the Marche, ruled at this juncture by the Papacy. He was the eldest son of the arch-conservative Count Monaldo Leopardi and the Marchioness Adelaide Antici, members of the landowning aristocracy. Because of the Count’s improvidence, the couple were forced to live in somewhat reduced circumstances. Most of their property was heavily mortgaged during Giacomo’s childhood, although they managed to provide private tutors for their three children.

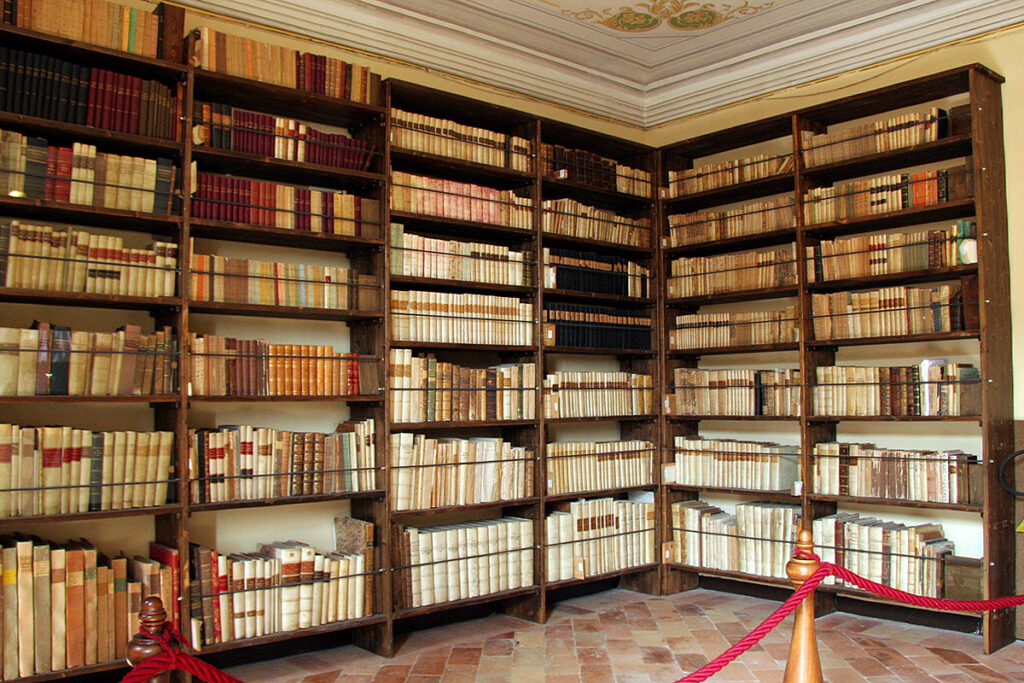

Giacomo, seemingly destined for a brilliant career in the church, had access to his father’s library with its 10,000 volumes. It was here that he taught himself Ancient Greek and Hebrew (amongst other languages) after his formal education was completed, and it was here also that he compiled many of the learned entries for his secret diary or notebook, the Zibaldone, or “hotchpotch” of ideas. This remarkable work by the greatest prose writer of the 19th century (according to Nietzsche) was never published during the author’s lifetime. For many years, it lay buried in a trunk and was only discovered around 1898.

Leopardi’s Library in his house in Recanati

This is the first complete English edition of the Zibaldone, although a complete French edition appeared in 2004. Editors Michael Caesar and Franco D’Intino are to be commended for bringing this daunting task to fruition. John Gray is right – this represents “a major event in the history of ideas” and is “a triumph of scholarship”*. The scale of the undertaking becomes readily apparent when you peruse the book. The wide range of complex subjects addressed, in such diverse fields as philology, philosophy (including political philosophy), history, literature and the ancient classics and the numerous, extended quotations from classic texts, both old and new, in several different languages, bespeak the author’s erudition. A team of seven principal translators was required by the editors along with an advisory board of experts. Caesar and D’Intino also drew on the expertise of specialist consultants for specific issues that arose in certain subjects.

Of the 4,526 pages of the original version of the Zibaldone, 4,006 were written between 1817 and 1823. By a strange coincidence, another no less famous “exponent and justifier of pessimism”**, Arthur Schopenhauer, was writing his magnum opus, Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (The World as Will and Idea, 1819) at around the same time.

Both Leopardi and Schopenhauer contend that life contains infinitely more pain than pleasure. Indeed, nobody, in the former’s judgement, would want to re-live their life over again “exactly as they had done before” (Zibaldone, page 1,909). Only hope, that fountainhead of illusion, and the distractions provided by study or by the contemplation of beauty make life bearable. Evil evidently exists in the very nature of things given that some animals are born to be the prey of other species (Z, page 2,059). Yet man alone “actually knows of death” (Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms, ‘On the Suffering of the World’) so that animals, who live only in the present, generally suffer less than humans. In a beautiful and compelling passage, Leopardi recalls the fable of Psyche, who was happiest when she knew nothing. He notes likewise that in Genesis, knowledge is depicted as the enemy of happiness and concludes that “my system was pleasing to the ancients of the earliest times” (Z, pp 329-330).

Happiness is an illusion, in Leopardi’s estimation. Ditto the consolations of religion and the notion of progress***. Viewed rightly, death should therefore be considered the supreme good (Z, page 392). On the last page of the Zibaldone we have the following heartfelt observation – “Two truths that men will generally never believe: one, that we know nothing, the other, that we are nothing. Add the third, which depends a lot on the second: that there is nothing to hope for after death.” (Z, page 2,071). Schopenhauer would surely have agreed.

Unlucky in love, prone to depression and loneliness since his childhood****, suffering from a hunchback and other maladies possibly attributable to excessive study, including at times near-blindness, it would be an easy take to attribute Leopardi’s bleak view of nature to his personal experiences (a criticism that he himself anticipated and refuted). Yet other thinkers, notably Schopenhauer and Freud, who lived much different lives, came to very similar conclusions. Leopardi’s discovery of the Greek tragedies in 1823 only reinforced his belief in the universal truth of his “system” of radical pessimism.

Tim Parks in the New York Review of Books (October 10th 2013) called the Zibaldone “The Greatest Intellectual Diary of Italian Literature”. Make that “Literature”, period.

Leslie Jones, April 2014

©

Leslie Jones is the Deputy editor of the QR

ENDNOTES:

*Quotations from ‘The barbarism of reason: John Gray on the Notebooks of Leopardi’, New Statesman, 26th September 2013

**Quotation from RJ Hollingdale, introduction to Arthur Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms, Penguin 1978, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, page 36

***Leopardi claims that there has been no increase of knowledge because we have lost many of the teachings of the ancients (Z, p 2056). However, periods of rebirth are possible

****Even as a child, the idea of death tormented him (Z, pp 332-333)