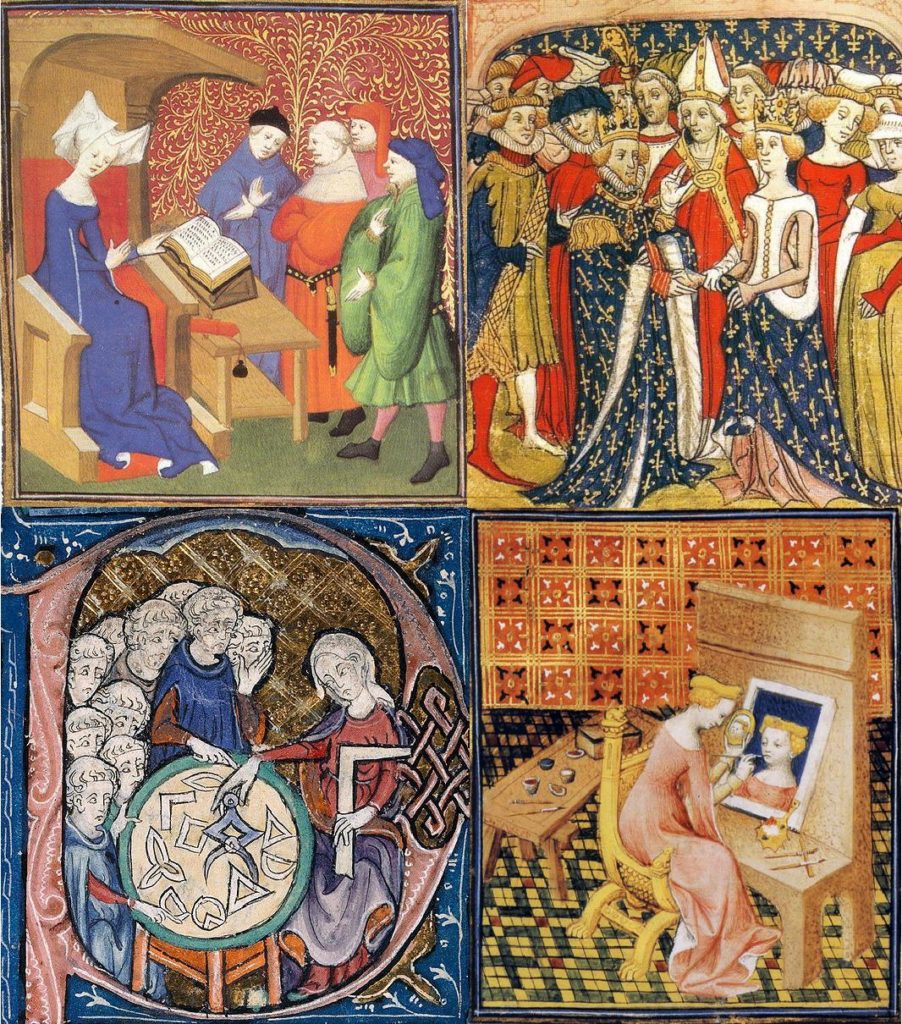

Women Activities in the Middle Ages

Pre-Renaissance Man

HENRY HOPWOOD-PHILLIPS is impressed by an audacious re-imagining of medieval thought

Inventing the Individual – The Origins of Western Liberalism

Larry Siedentop, London: Allen Lane, 2014, 448 pps

Larry Siedentop’s introduction gets straight to the point. We have ‘lost our moral bearings’, we ‘lack a narrative of ourselves’, indifference and permissiveness characterise a West that has been left unmoored and dissolute by the tides of history. Complacency is the tenor of an age which has forgotten that belief-systems must still compete; Islamic fundamentalism and the ‘crass utilitarianism’ of China constitute very real threats today.

In his epilogue, the author emphasises how the West rests on shared beliefs, best outlined today as liberalism – and that the greatest peril to its future success lies within our self-understanding of how its philosophy evolved. Typically abridged and truncated poorly in conventional narratives, this point especially concerns how we understand the Middle Ages and Christianity’s role in establishing individuality, equality and freedom as lodestars of the West’s collective conscience. General audiences, victims of this bowdlerisation of History, forget that the instincts that forged these values were created and honed by the Church in the first place, before they were turned against it.

The book constitutes no less than a rebalancing act of the entire Western historical canon. What drives this ambitious project?

If we do not understand the moral depth of our own tradition, how can we hope to shape the conversation of mankind?

Siedentop demands.

The Middle Ages must be re-acknowledged as a period of serious achievement in furthering the values of individuality, equality and freedom. Too often written off as a black hole defined and illuminated by its bookends, antiquity and modernity, Siedentop works hard to restore it to prominence.

The author’s shift of the historiographical centre of gravity away from the anti-clerical Enlightenment of the Philosophes has serious ramifications.

The importance of the Renaissance has been grossly inflated to create a gap between early modern Europe and its preceding centuries – to introduce a discontinuity that is misleading

he explains, as he attempts to restore proportion to the historical landscape. He is quite clear that history has been choreographed for too long to appear as though liberal ideals somehow emerge from nowhere after a senescence of over a millennium.

In Siedentop’s re-reading, antiquity was not the secular, tolerant and free lost-land many modern thinkers anachronistically paint it. Instead, it was a world in which every possible unit: family, paterfamilias, clan, city and imperial leader operated as a quasi-church, each suffused with the ideas and language of religion. As a result, the individual had no real existence outside these institutions, being entirely defined by them.

Even non-personal aspects of society, law and property for instance, were considered through a religious lens. The intellectual world was infused with the idea that paideia and pietas were consubstantial. Reason was a tool that commanded morality and social hierarchy. Liberty was nothing, the res publica everything.

This is all set against a Judaism that treated Law as ‘Yahweh’s will’, separating truth from society’s demands and channelling it instead as an external command. This type of thinking invades the West at first with Jesus’ incarnation, and second, with Paul, its great expositor.

According to Siedentop, Paul is one of the great underrated revolutionaries of history. His key theme, that the incarnation was proof that God operated a hotline to people on an individual level, effectively bypassed every other factor that constituted a person’s corporate identity, and would eventually turn almost every contemporary notion of society on its head. ‘There is neither Jew not Greek, neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus’, Paul said. And this fundamental identity rendered each and every soul to be equal, individual and deserving of a dignity (a germ of jus naturale) that included liberty.

The rest of the book is essentially a re-investigation of history with the pivot placed on this Pauline revolution. It throws up some very surprising results. Just to touch upon a few of the most significant:

- Aristotle and Plato are depicted as reactionaries trying to resist the sophists’ challenge to the old assumption that nature and culture sleep in the same bed.

- Augustine is less a crusty Church Father than a restorer of will to its rightful place in partnership rather than in subjection to Reason; a discoverer of the pre-social self, the original existentialist.

- The Gnostics are not so much hippy Christians with loose and free theologies, as conservatives who felt uncomfortable jettisoning the platonic framework of how knowledge and society connected.

But the big idea that is tirelessly tracked throughout the book is the ‘equality of souls’, an idea that contributed to:

- Turning work from a shameful activity into one that bestowed self-respect.

- Informing the notion that was a difference between power and rightful authority (especially through Duns Scotus and William of Ockham).

- Converting heroism from social notoriety into martyrdom – the witnessing of a conscience acting against the norms of society.

One of the biggest surprises is how the Church worked against feudalism. The two are often conflated in the Western imagination. But Siedentop reminds the reader that though the Church ‘adjusted’ to it, it ‘could not endorse it’, for only God owned souls.

The general reader will also be astonished to see the Cluniac reforms and the centralisation of the Papacy read through the lens of notional equality rather than ecclesiastical power-games. As Guizot (heavily leaned on by Siedentop throughout) inferred, it was in the space between the temporal and the newly legitimized spiritual sphere that liberty of conscience developed.

Larry Siedentop

Breathless revisionism on such a grand scale deserves high praise. Hugh Trevor-Roper used to compare specialist-historians to snipers who would take pot-shots at anybody brave enough to attempt works of synthesis. It requires fortitude and insouciance to range so far and wide in the minefield that is medieval studies – a discipline with opinions that range from Chris Wickham on the one hand to Jacques Le Goff on the other.

Siedentop also deserves credit for rehabilitating the study of History as a place where narratives can flower as a cause for good. For too long, historiography has been the universe of impenetrable texts. The subject’s relevance suffers in such circumstances. Siedentop has sought to give the West its story back. He will doubtless attract numerous detractors for daring to do so.

HENRY HOPWOOD-PHILLIPS works in publishing