Perfidious Albion

The United States’ Entry into the First World War: the Role of British and German Diplomacy, Justin Quinn Olmstead, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2018, hb, 206 pp, reviewed by Leslie Jones

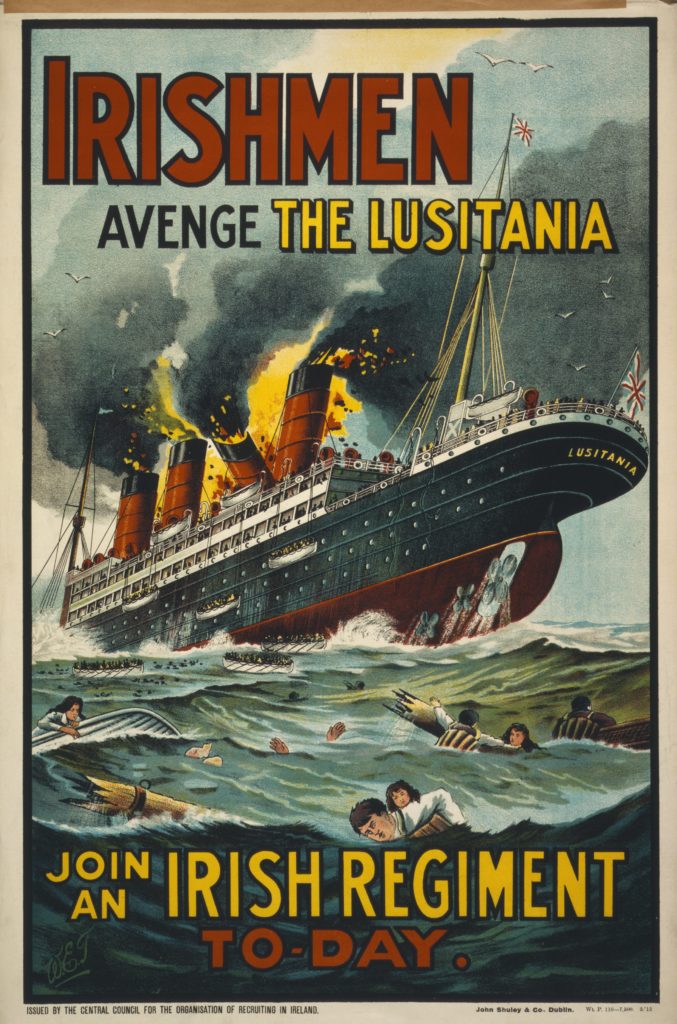

In 1914, the majority of Americans wanted to avoid US involvement in the European war. Indicatively, two thirds of 367 American newspaper editors surveyed by the Literary Digest supported neither side. But just as today, there was a gulf between the views of the eastern elite and those of the heartland. Concerning the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, the Chicago Tribune commented that since Britain did not obey international law, why should Germany? In contrast, a recurrent theme of articles in the New York Herald and New York Times was that Germany was bent on world domination. British propagandists worked tirelessly to demonise the Kaiser-Reich. At times, Wilhelm II played into their hands, as when he urged troops, embarking for China to suppress the Boxer rebellion, to “…beat him [the enemy] …give no pardon and take no prisoners”.

Diplomacy and propaganda dovetailed in Britain’s efforts to draw the US into the war and of those of Germany to keep her out. For Germany, “the maintenance of American neutrality was key”. President Woodrow Wilson and his Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan were relatively untutored in foreign affairs and depended on the advice of Robert Lansing, Counselor of the US Department of State. Wilson’s inexperience in foreign affairs was compounded by depression, following the death of his wife Ellen in August 1914.

British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey identified certain elements in the twenty-eighth President’s make up that could be manipulated, notably his affection for England (like Grey, Wilson loved the poetry of Wordsworth) and his morality (or messiah complex). Grey assiduously cultivated both Colonel Edward M House, Wilson’s confidant and special envoy, and Walter Hines Page, American Ambassador to the Court of St James. The author depicts Page, who was pro-British, as a pliant tool. Following the sinking of the British liner Lusitania on 7th May 1915, with the loss of 124 American lives and 5000 shells, he told Wilson that the US should declare war or forfeit the respect of the world.

Count von Bernstorff, Germany’s ambassador to the United States, insisted that Germany posed no threat. In May 1914, Colonel House visited Germany and was feted by the Kaiser who assured him, likewise, of Germany’s abiding friendship for America. But bellicose statements by Admiral Tirpitz unsettled House.

Grey realised from the outset that using the British navy to strangle Germany’s war effort would cause problems with the US and other neutrals. His objective was “…to secure the maximum of blockade…without a rupture with the United States”. America’s sole interest in 1914 was neutral rights and the freedom of the seas which allowed her to trade with all nations. Yet, in the event, Grey eventually persuaded the United States government to acquiesce in Britain’s wartime modifications to the Declaration of London (1909). The Declaration had outlawed “general capture” of enemy commerce on the high seas during wartime. However, the British Order in Council of 20th August 1914 justified the seizure of ships carrying goods to Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway i.e. goods destined for neutral nations.

Grey placated Ambassador Page by promising that Britain would treat US ships as friendly neutrals and would endeavour to purchase any ‘innocent contraband’ in American ships. He expedited hearings on detained US cargoes and offered to purchase the cargoes of US ships in prize courts. The British blockade of Germany, accordingly, was not generally perceived by American diplomats as a serious threat to American commerce.

Olmstead does not mince his words. He believes that “British diplomats thoroughly dominated their American counterparts” and that the US government, in practice, acquiesced in Britain’s illegal blockade and thereby “became an unwitting accomplice in Britain’s throttling of the German people…”. By ensuring “…a benevolent and neutral United States”, blockade notwithstanding, and by maintaining good relations with the US, Grey laid the basis for the eventual entry of the US in the war. His tactics were arguably “…the decisive element in the defeat of Germany and the Central Powers.”

The British blockade, declared in August 1914, was soon extended to food and was known in Germany as the ‘starvation blockade’. In February 1915, Germany retaliated, declaring the waters around the British Isles to be a war zone. Ships entering the zone were liable to destruction. The objective of this counter-blockade was to force Britain into submission by cutting off supplies of food and munitions from America and the Empire.

Grey considered Germany’s submarine campaign “a stroke of good fortune”. The decision to blockade Britain was initially opposed by Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg because it might antagonise neutral countries, notably the United States. It was taken by the Kaiser, on the advice of Admiral Hugo von Pohl, Chief of the Admiralty Staff. Responding to Germany’s war zone declaration, US ambassador Gerard delivered a stiff note of protest to the German Foreign Office, threatening to “hold the Imperial Government to a strict accountability” for any loss of American lives or ships. The contrast between Wilson’s toothless response to Britain’s naval blockade of Germany, on the one hand, and to the latter’s use of submarine warfare on the other, is striking. Revealingly, in a discussion in 1915 with his secretary Joseph Tumulty, Wilson opined that “England is fighting our fight [and]…I shall not…place obstacles in her way”.

According to the distinguished American historian Charles Seymour, writing in 1934, German submarine warfare made US entry into the war inevitable. Yet as Olmstead points out, Germany was able to undertake almost three years of submarine activity before Wilson asked Congress, in April 1917, for a declaration of war. Indeed, the submarine “brought Imperial Germany to the threshold of victory”, despatching over eleven million tons of Allied shipping (Patrick O’ Sullivan, The Lusitania: Unravelling the Mysteries, 1998).

British and German diplomacy throughout the Great War was subordinated to the overriding goal of achieving military victory by all means necessary. Olmstead pithily characterises the response of the British and German Foreign Offices towards American attempts to mediate as “posturing for peace”. Both Britain and Germany sought to persuade the United States that they wanted an end to the war. As the author avers,“…old age and cunning will always overcome youth and enthusiasm”.

Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House

When I was teenager I took a book out of the local library titled, Prussian Political Philosophy. Even as a youth I could tell that the sole purpose of the book was to blacken Germany’s name circa 1910. It was published in the UK, and was my first experience of propaganda masquerading as honest political scholarship. The run up to WWI indeed.