Jimmy Savile

Pedal Power

The Vice of Kings: how Socialism, Occultism and the Sexual Revolution Engineered a Culture of Abuse, Jasun Horsley, London, Aeon Books, 2019, 323pp., reviewed by Ed Dutton

When ‘national treasure’ Jimmy Savile died in 2011, copious revelations emerged about the entertainer’s decades of predatory sexual abuse against teenage girls. Senior figures in the BBC claimed innocent ignorance, despite the fact that there had long been rumours about Savile’s proclivities, with some of the milder forms of abuse having occurred ‘in plain sight,’ such as Savile groping a girl on Top of the Pops. This resulted in ‘Operation Yew Tree,’ with frequently fruitless investigations into other celebrities, including Sir Cliff Richard and two well-known actors from Coronation Street. All were eventually exonerated. In its worst excesses, Yew Tree gave free rein to conspiracy theorists’ more outlandish, paranoid ideas.

Some believed – on the grounds that Sir Jimmy Savile and the late Liberal MP Sir Cyril Smith had been child abusers – that Britain had been run by a clique of high-powered paedophiles. They accepted the fantasies of one Carl Beech. He posited a VIP paedophile ring that included former Prime Minister Edward Heath, former Home Secretary Leon Brittan, former Conservative MP Harvey Proctor and numerous others. Labour MP Tom Watson told parliament that he had ‘clear intelligence suggesting a powerful paedophile network linked to parliament and Number 10’ after meeting with Beech, who it turned out was himself a downloader of child pornography.

Why are conspiracy theories so attractive? What evolutionary psychologists call ‘hyper-active agency detection’ is the tendency to err on the side of assuming agency. In pre-history, if you heard a noise in the forest and wrongly assumed it was a wolf, rather than the wind, you lost nothing. However, if you wrongly assumed it was the wind rather than a wolf, you lost everything. So, we are programmed to be paranoid, with some of us more paranoid than others and, thus, more likely to accept conspiracy theories based on tenuous evidence. For similar reasons, we are hard-wired to over-detect patterns. If we are presented with images of randomly placed dots, we tend to find patterns, because in prehistory, the person that failed to do so could lose everything. Conspiracy theorists are especially prone to pattern over-detection. There are no coincidences in their world.

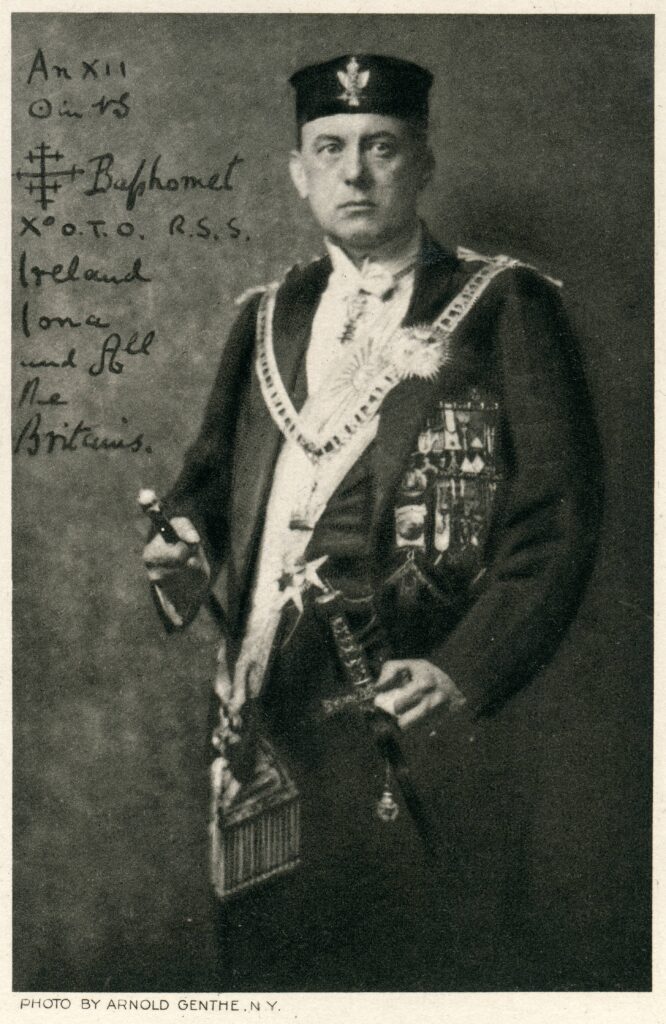

This brings me to The Vice of the Kings, by Jasun Horsley. His argument is that the Fabian Society, in a misguided and often scientifically illiterate attempt to improve humanity, sought to break down traditional sexual mores. Some people who were connected to the Fabian Society took this further, hoping to liberate the supposed sexuality of children. These people – who knew Fabians, who either were Fabians, or who knew of their ideas – included the infamous occultist Aleister Crowley. And these Fabian ideas supposedly influenced high level child abusers and even teachers at private boys’ schools, such as those attended by Horsley, which had long acted as a kind of hazing ritual for the upper class.

If this were all that Horsley were arguing, then one might conclude that here we have an interesting and thought provoking book. However, this is not all that he is arguing. He is also maintaining that ‘we have been engineered’ (p.82), as part of giant conspiracy, to accept a culture of child abuse. But Horsley fails to present any clear evidence for this assertion. All we have is the insinuation that because this leftist academic knew this Labour MP, and this Labour MP was at university with this spy, and this spy knew the author’s grandfather (who ran Northern Foods and who did such-and-such) . . . there is an enormous web, in Britain, of high level people, either actively promoting paedophilia or effectively enabling it. But this is hardly a plausible argument; it is only the allegation of a series of connections. And they are not unlikely connections given that influential people in various fields will gravitate towards each other. Furthermore, Horsley assumes that ‘association’ mean ‘causation’. He avers that ‘Fabianism, Quakers, Wicca, Theosophy, children’s education, “a return to nature”, sexual freedom, all tied together via the school I and my siblings end-up at. Who knew?’ (p.36). But that is not a demonstration. Once again, it is insinuation.

At the beginning of Chapter 4, having treated us to a taster course in his ‘insinuation’ and ‘association’ method, Horsley unintentionally lets slip how faulty his argumentation is. He writes: ‘It would be nice if, somehow, I could lay all of this information out as a straightforward, linear narrative; but that would be like hoping to put a leash on an octopus. If the connections I am attempting to map were simple, straightforward and linear, they would already be obvious for us all to see’ (p.27).

Consider, next, a typical example of how Horsley argues and how he writes:

‘And not only did the budding new dance culture overlap with the crime underworld populated by the Kray twins and Jimmy Boyle (and possibly Ian Brady, Myra Hindley, and Savile’s pal Peter Sutcliffe), it also intersected with the arrests of Members of Parliament, from social reformers like Acland to occult-dabblers like Driberg and known child-molesters like Lord Boothby. Is it a leap to suppose the Savile’s involvement with the world of dance music was part and parcel with this connection to, or employment by, government agencies?’ (pp.58-59).

Yes, it is. This is moving from association to causation and making a huge assumption in the process, about an enormous conspiracy of abuse which, somehow, wouldn’t leak out.

Putting this fundamental flaw aside, The Vice of Kings is a painful and irritating read; there are long, meandering sentences peppered with clauses and parentheses; constant and unnecessary block quotes, including some from the author’s own previous works, including a three page block quote from his diary; and the self-indulgent manner – “Ted Hughes (whom I met as a child)” (p.75) – in which he magnifies the significance of his family as unwitting players in this alleged child abuse conspiracy. Then there are short chapters that lack sufficient depth to persuade, and the intimations, in throw away remarks, of further conspiracies that are never substantiated – e.g. ‘the last bomb to go off in a series of coordinated “terrorist” attacks in central London’ (p.92).

This book proposes such an audacious theory that one almost wants the author to convince. But he comes nowhere near to doing so. In the end, The Vice of Kings is little more than an unwitting exercise in ‘hyper-active agency detection’ and ‘pattern over-detection’.

Aleister Crowley, as Baphomet

Dr Edward Dutton is the author of numerous books, including Churchill’s Headmaster: the ‘Sadist’ Who Nearly Saved the British Empire (Manticore Press, 2019). He runs the internet channel The Jolly Heretic on YouTube and Bitchute

Like this:

Like Loading...

Pedal Power

Jimmy Savile

Pedal Power

The Vice of Kings: how Socialism, Occultism and the Sexual Revolution Engineered a Culture of Abuse, Jasun Horsley, London, Aeon Books, 2019, 323pp., reviewed by Ed Dutton

When ‘national treasure’ Jimmy Savile died in 2011, copious revelations emerged about the entertainer’s decades of predatory sexual abuse against teenage girls. Senior figures in the BBC claimed innocent ignorance, despite the fact that there had long been rumours about Savile’s proclivities, with some of the milder forms of abuse having occurred ‘in plain sight,’ such as Savile groping a girl on Top of the Pops. This resulted in ‘Operation Yew Tree,’ with frequently fruitless investigations into other celebrities, including Sir Cliff Richard and two well-known actors from Coronation Street. All were eventually exonerated. In its worst excesses, Yew Tree gave free rein to conspiracy theorists’ more outlandish, paranoid ideas.

Some believed – on the grounds that Sir Jimmy Savile and the late Liberal MP Sir Cyril Smith had been child abusers – that Britain had been run by a clique of high-powered paedophiles. They accepted the fantasies of one Carl Beech. He posited a VIP paedophile ring that included former Prime Minister Edward Heath, former Home Secretary Leon Brittan, former Conservative MP Harvey Proctor and numerous others. Labour MP Tom Watson told parliament that he had ‘clear intelligence suggesting a powerful paedophile network linked to parliament and Number 10’ after meeting with Beech, who it turned out was himself a downloader of child pornography.

Why are conspiracy theories so attractive? What evolutionary psychologists call ‘hyper-active agency detection’ is the tendency to err on the side of assuming agency. In pre-history, if you heard a noise in the forest and wrongly assumed it was a wolf, rather than the wind, you lost nothing. However, if you wrongly assumed it was the wind rather than a wolf, you lost everything. So, we are programmed to be paranoid, with some of us more paranoid than others and, thus, more likely to accept conspiracy theories based on tenuous evidence. For similar reasons, we are hard-wired to over-detect patterns. If we are presented with images of randomly placed dots, we tend to find patterns, because in prehistory, the person that failed to do so could lose everything. Conspiracy theorists are especially prone to pattern over-detection. There are no coincidences in their world.

This brings me to The Vice of the Kings, by Jasun Horsley. His argument is that the Fabian Society, in a misguided and often scientifically illiterate attempt to improve humanity, sought to break down traditional sexual mores. Some people who were connected to the Fabian Society took this further, hoping to liberate the supposed sexuality of children. These people – who knew Fabians, who either were Fabians, or who knew of their ideas – included the infamous occultist Aleister Crowley. And these Fabian ideas supposedly influenced high level child abusers and even teachers at private boys’ schools, such as those attended by Horsley, which had long acted as a kind of hazing ritual for the upper class.

If this were all that Horsley were arguing, then one might conclude that here we have an interesting and thought provoking book. However, this is not all that he is arguing. He is also maintaining that ‘we have been engineered’ (p.82), as part of giant conspiracy, to accept a culture of child abuse. But Horsley fails to present any clear evidence for this assertion. All we have is the insinuation that because this leftist academic knew this Labour MP, and this Labour MP was at university with this spy, and this spy knew the author’s grandfather (who ran Northern Foods and who did such-and-such) . . . there is an enormous web, in Britain, of high level people, either actively promoting paedophilia or effectively enabling it. But this is hardly a plausible argument; it is only the allegation of a series of connections. And they are not unlikely connections given that influential people in various fields will gravitate towards each other. Furthermore, Horsley assumes that ‘association’ mean ‘causation’. He avers that ‘Fabianism, Quakers, Wicca, Theosophy, children’s education, “a return to nature”, sexual freedom, all tied together via the school I and my siblings end-up at. Who knew?’ (p.36). But that is not a demonstration. Once again, it is insinuation.

At the beginning of Chapter 4, having treated us to a taster course in his ‘insinuation’ and ‘association’ method, Horsley unintentionally lets slip how faulty his argumentation is. He writes: ‘It would be nice if, somehow, I could lay all of this information out as a straightforward, linear narrative; but that would be like hoping to put a leash on an octopus. If the connections I am attempting to map were simple, straightforward and linear, they would already be obvious for us all to see’ (p.27).

Consider, next, a typical example of how Horsley argues and how he writes:

‘And not only did the budding new dance culture overlap with the crime underworld populated by the Kray twins and Jimmy Boyle (and possibly Ian Brady, Myra Hindley, and Savile’s pal Peter Sutcliffe), it also intersected with the arrests of Members of Parliament, from social reformers like Acland to occult-dabblers like Driberg and known child-molesters like Lord Boothby. Is it a leap to suppose the Savile’s involvement with the world of dance music was part and parcel with this connection to, or employment by, government agencies?’ (pp.58-59).

Yes, it is. This is moving from association to causation and making a huge assumption in the process, about an enormous conspiracy of abuse which, somehow, wouldn’t leak out.

Putting this fundamental flaw aside, The Vice of Kings is a painful and irritating read; there are long, meandering sentences peppered with clauses and parentheses; constant and unnecessary block quotes, including some from the author’s own previous works, including a three page block quote from his diary; and the self-indulgent manner – “Ted Hughes (whom I met as a child)” (p.75) – in which he magnifies the significance of his family as unwitting players in this alleged child abuse conspiracy. Then there are short chapters that lack sufficient depth to persuade, and the intimations, in throw away remarks, of further conspiracies that are never substantiated – e.g. ‘the last bomb to go off in a series of coordinated “terrorist” attacks in central London’ (p.92).

This book proposes such an audacious theory that one almost wants the author to convince. But he comes nowhere near to doing so. In the end, The Vice of Kings is little more than an unwitting exercise in ‘hyper-active agency detection’ and ‘pattern over-detection’.

Aleister Crowley, as Baphomet

Dr Edward Dutton is the author of numerous books, including Churchill’s Headmaster: the ‘Sadist’ Who Nearly Saved the British Empire (Manticore Press, 2019). He runs the internet channel The Jolly Heretic on YouTube and Bitchute

Share this:

Like this: