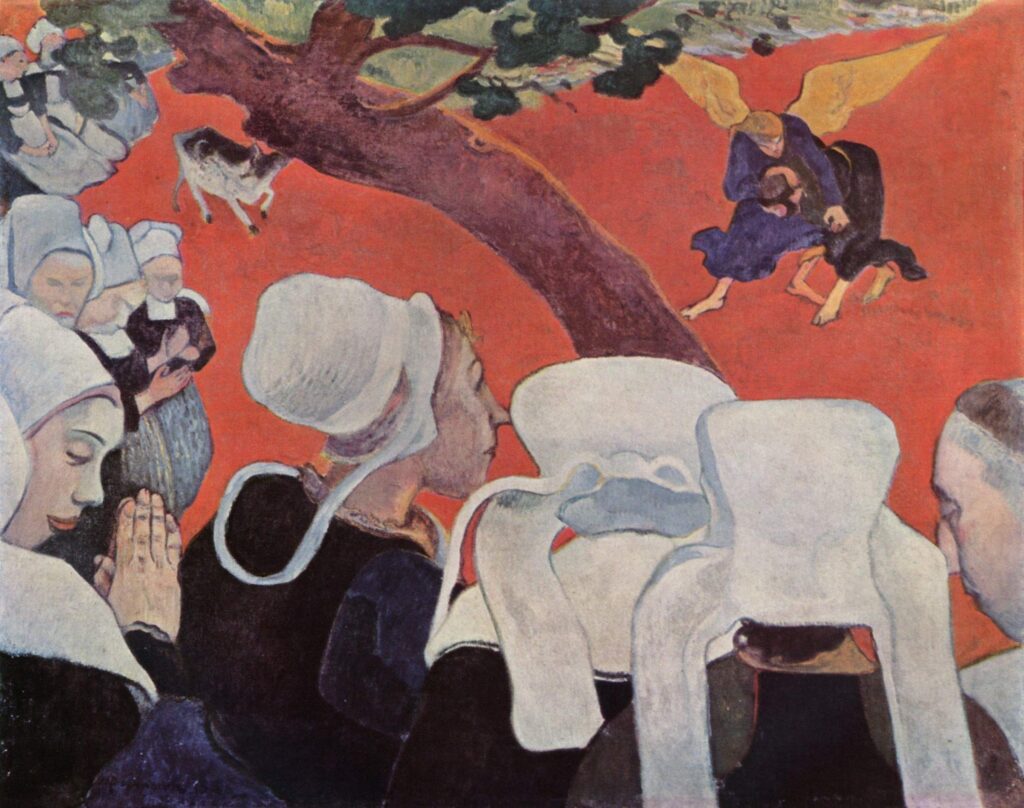

Paul Gauguin, The Vision of the Sermon, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1888

credit Wikipedia

Pauline Conversion

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, National Gallery, 22nd March 2023, curated by MaryAnne Stevens; After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, Catalogue of the Exhibition, National Gallery Global, 2023, reviewed by Leslie Jones

After Impressionism covers the supposedly pivotal period from 1886 (the date of the eighth and last Impressionist Exhibition in Paris) to 1914. The curator MaryAnne Stevens maintains that modern art was invented in this era and that a key factor here was the transition to “…non-naturalism, albeit expressed in various degrees from a modest distortion of reality to pure abstraction”. New painting techniques were developed and the artistic ideals of Greece and Rome that had informed the French academic tradition took a battering. Contemporaneously, there was what historian of ideas H Stuart Hughes called “the revolt against Positivism” (see his Consciousness and Society, 1958).

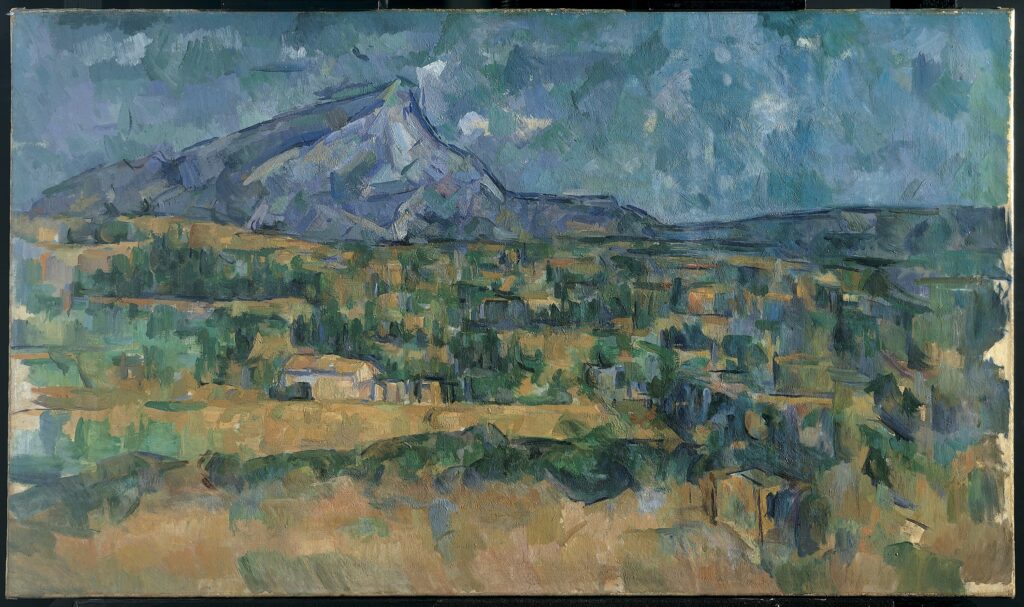

Paul Gauguin was emblematic in this context. Like Thomas Carlyle, author of On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841), Gauguin thought that “artists, like priests, were individuals with special powers…”, who gave “physical form to great ideas”. The Vision of the Sermon, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1888) symbolises a man, possibly Gauguin himself, fighting with his inner demons. Abandoning perspective, Gauguin believed that the aesthetic quality of a painting should “…no longer be measured by the accuracy of its representation of the natural world” (Stevens, Catalogue). In the still life Fête Gloanec, (1888), an assemblage of objects “appears to float rather than sit on the round table”. In The Wave (1888), the horizon is eliminated and the genre of the landscape painting thereby subverted. In Paul Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire (1902-6), likewise, recession is negated “through horizontal bands of colour”. And, in his portrait of his wife Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1888-90), there is an emphasis on the “rectangular forms of the chair back, fireplace and mirror frame”. The dress itself, on closer inspection, seems “insubstantial, not solid”.

Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902-6, credit Wikipedia

Memory and feeling, for Gauguin, were infinitely more important than direct observation. “Don’t copy too much after nature. Art is an abstraction…”, he advised fellow members of the Pont-Aven School in 1888. In the Wine Harvest, he once again transcends “direct transcription”. An incongruous seated figure in the foreground recalls a Peruvian mummy that the artist saw in the Ethnographic Museum in Paris. Gauguin and Émile Bernard reportedly argued about who invented “pictorial symbolism”; but both simplified figures at the expense of three dimensionality, intensified colour and flattened forms by “bounding them in heavy outlines”. Thus, in Bernard’s The Pardon, Breton Women in a Meadow (1888), the field is depicted as “a flat green plane”.

The Pardon, Breton Women in a Meadow, Émile Bernard, credit Wikipedia

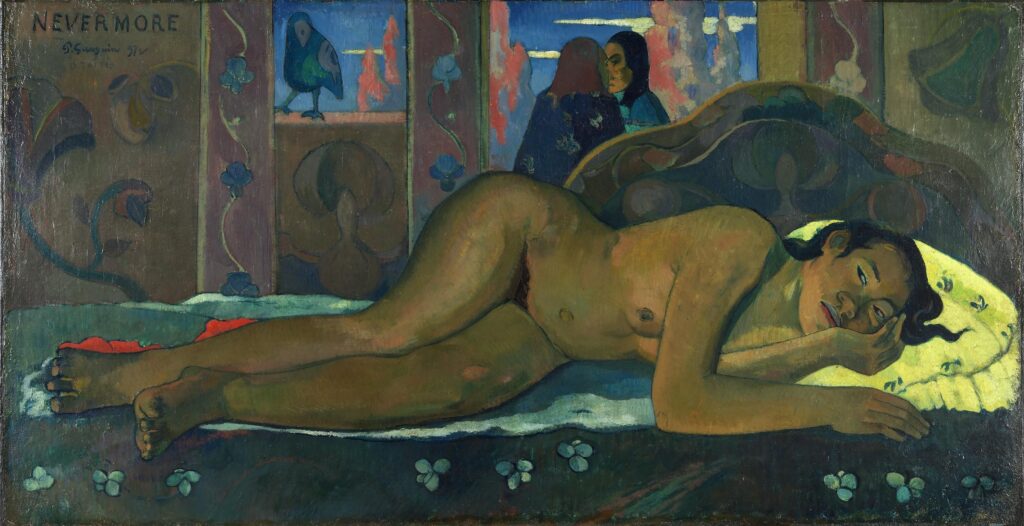

In 1891 and 1893, Gauguin made extended visits to Tahiti, which had become a French colony in 1880. According to art historian Julian Domercq, Gauguin’s conception of Polynesian art as “primitive” and therefore more “authentic”, can be “inscribed…within the traditions of colonialism”. In Nevermore (1897), a raven references the eponymous 1845 poem by Poe and conveys the artist’s sadness about the destruction of Tahitian culture under the impact of French colonialism. Domercq insists, nonetheless, that Gauguin was himself in thrall to “colonialist and misogynist fantasies about Polynesian girls being sexually precocious”, taking several adolescent girls as “wives” (see Appropriating the ‘Primitive’; Modernism’s Debt to Non-Western Art, Catalogue).

Paul Gauguin, Nevermore, credit Wikipedia

After Impressionism focuses not just on the artists who drove “the ineluctable advance… of modernism into the twentieth century” but also on the “centres of persistent commitment to the avant-garde”, notably Brussels, Barcelona, Berlin and Vienna. Stevens calls these “cities in ferment” (Catalogue). She discerns a fruitful dialogue between painting and sculpture. Works by Rodin, namely The Walking Man, 1905-7 and a plaster cast of Monument to Balzac (1898), are juxtaposed with paintings, notably Le Bois sacré cher aux arts et aux muses (1884), by Puvis de Chavannes.

For Cézanne and his admirers, official art ie. art approved of and selected by the academies, was a bête noire. Ditto for the artist and sculptor Umberto Boccioni, who is strangely omitted from this exhibition. In 1907, Boccioni moved to Milan, the home of Futurism. One of recurring themes of the Futurist movement, which he eloquently articulated, was “the oppressive burden of the past for young artists”, (quotation, page 73, Inventing Futurism, 2009, by Christine Poggi). In his diary in 1907, Boccioni called the conventional repertory of artistic subjects (“fields, tranquility, little houses, woods etc”) an “emporium of modern sentimentalism” (and see Leslie Jones, ‘Futurism dissected’, QR, Summer 2009).

Umberto Boccioni, The City Rises, 1910-11, credit Wikipedia

A highlight of this ambitious exhibition is a set of canvases by Degas. In Dancers Practising in the Foyer (1880-9), there are “empty spaces and occluded figures”. “Form is intimated rather than clearly defined”. Concerning Woman Reading (about 1883-5), the woman is “stiched” into her surrounding and “the volume of her figure” negated. In Combing the Hair (1896), likewise,

Degas, Combing the Hair, credit Wikipedia