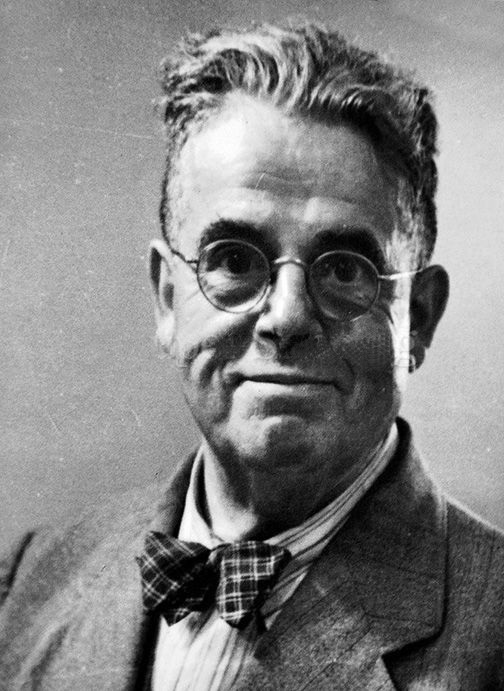

Karl Barth

No Ordinary Scholar

Christiane Tietz (Transl. by Victoria J. Barnett), Karl Barth, A Life in Conflict, Oxford University Press, 2021. Pp. I-XVII, 1-448. $32.95. Reviewed by Darrell Sutton

The names of those who have made noteworthy contributions to systematic theology are few indeed. Due to the publication of his four massive treatises, titled Kirchliche Dogmatik/Church Dogmatics – (divided into twelve half-volumes – with an unfinished 13th), Karl Barth (1886-1968) now towers above twentieth century professors of theology in nearly every way. Published between 1932 and 1967, and at more than 9000 pages consisting of close to six million words, Church Dogmatics (CD) is a theological reference work whose value continues to appreciate in select circles.

Only a small group of professional theologians may lay claim to grand reputations. Of them all, none exhibited the same encyclopedic genius that Karl Barth displayed, except perhaps for B.B. Warfield (1851-1921). So prodigious, so fecund was Barth that only Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), thanks to his comprehensive Summa Theologica, can be compared to him. No one should deny the imprint of originality that Barth imposed upon his scholarly works. Aspects of his aptitude in historical theology, ethics, philosophy, church history and exegesis are underscored in this biography.

The Biography of Karl Barth

For authorities, and newcomers to the field of Barth studies, Dr. Tietz has written a delightful book, one whose virtues are everywhere in evidence. An immense amount of research went into this undertaking. It is informative from beginning to end. She was inspired to read Barth’s writings by Eberhard Jüngel (1934-2021) when she was his student. She acknowledges her work also ‘owes much’ to Eberhard Busch’s Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts. There are fourteen chapters in Karl Barth A Life in Conflict (KBLC) followed by an Epilogue, Chronology, Bibliography, and Index. As expected, Barth is quoted profusely. There are numerous illustrations and hundreds of end-of-chapter notes. In fact, reviewing the notes and sources is more than tedious. But Victoria Barnett’s translation is clear.

KBLC follows a chronological path. As noted in each chapter heading, specific years are treated: e.g. 1 “I Belong to Basel” Ancestors and Childhood, 1886-1904. Born in Basel Switzerland, there were a few illustrious clerics and divines amongst his forbears. He was a distant relative of Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1897), the cultural historian of the Renaissance (p.7). Born in the wake of Germany’s Kulturkamf, Barth, in time, would also oppose what he perceived to be a-historical features of Roman Catholic dogma. By the year 1850, theological study was rooted deeply in the philology of early nineteenth century Germany. And although German critical scholarship was heralded for its conscientious rigor in Europe, it was regarded as a curiosity on the continent and in America. Eminent men adorned the lecture halls of Erlangen, Leipzig, Göttingen, Tübingen, Halle and Berlin etc., and by their teachings drew pupils from far and wide.

Augustinianism Lutheranism held sway in Church pulpits. In the classrooms it was different. Therein a liberal theology was born (cf. Karl Bornhausen, ‘The Present Status of Liberal Theology in Germany’, American Journal of Theology, 1914, Vol.18, No.2). Initially Barth learned the scientific methods of biblical-critical scholarship in his home under his father’s tutelage and from his writings. His father died in 1912 as a result of blood poisoning at the early age of 55; but not before Karl had been able to attend some of his father’s classes. The two of them could not agree on where Karl should study theology. In the end, Karl chose Berlin. There he grappled with Adolf Harnack’s (1851-1930) liberal views on scripture. In 1908-1909, he was an editorial assistant on Die Christlich Welt (The Christian World), under Martin Rade (1857-1940), through which articles from eminent theologians required Barth’s examination. By this time, Barth, who never studied for a doctorate, was audacious, even if he was quite modernistic in his religious views. However, parish work and a world war have a way of directing activist-minds toward other trends of thought.

For a time, he occupied the pulpit of Temple de l’Auditoire, one which had been filled in the sixteenth century by the Reformer John Calvin (1509-1564). Barth’s influence upon the congregation was minimal. Few attended. After he lamented the lax level of Sunday attendance, several more presented themselves for worship. In KBLC, Dr. Tietz’s coverage of this period is thorough, revealing that Barth ‘absorbed himself in Calvin’s main work The Institutes of the Christian Religion’ (p.48). And he busied himself writing short articles for the parish newsletter. From 1911 to 1921, Barth was pastor in Safenwil, in the canton of Aaragua. In 1913, he married Nelly Hoffman and they would have five children.

Karl Barth’s 1919 commentary on the Epistle to the Romans has been described as ‘a bomb that landed in the playground of theologians’ (p.90). The metaphor mixes fact with fiction. If there was an explosion, no theological constructs were thrown to the ground. Barth’s commentary generated extensive discussions, but it never altered the beliefs of any forceful scholar in the various theological camps. His remarks on Romans, though pithy, were inexact (p.124); nonetheless his arguments were adopted by philosophers of religion more so than by theologians who pursued narrower, logical lines of hermeneutics.

In 1921, Barth was asked by Johan Heilmann to take up a new honorary Professorship for Reformed Systematic Theology in Göttingen. His knowledge of Reformed theology was then thin. In his own words,

‘Calvin is a waterfall, a jungle, something demonic, something coming directly down from the Himalayas, absolutely Chinese, wonderful, mythological. I am utterly lacking in the organs, the suction cups, to only imbibe this phenomenon, let alone correctly portray it. I take in only a thin stream of water, and I can only convey in turn a thin extract of this thin stream of water. I would well and gladly sit and spend the rest of my only with Calvin’ (p.106).

But Barth soon became proficient in Reformed studies. In 1923, his lectures on the Theology of the Reformed Confessions became available. Alongside his colleagues, he pioneered dialectic theology, an academic form of exegesis that, neither positively nor negatively, affirms or denies absolutes regarding the incomprehensibility of God (p.135). The fullest expression of this method can be found in the newly founded journal of 1922 Zwischen den Zeiten (Between the Times) with contributions supplied by Barth, Friedrich Gogarten (1887-1967), Eduard Thurneysen (1888-1974) and under the editorship of Georg Merz (1892-1959). His years in Bonn eventually led him to depart from his friends’ interpretations (p.226f.).

Barth did not always get on well with colleagues: he admitted he did not grow close to any of them (p.269). He taught principles (ethics) that he did not apply to his personal life. The genius that he exhibited in his scholarship made it difficult for him to see peers as equals. At Münster, his relations seemingly were better with his fellow scholars. Yet they fell apart in the end over a dispute concerning who his successor should be (p.158). A similar quandary occurred once more when he retired from his professorship at Bonn (p.351). Despite his enormous popularity, few intellectuals found him congenial.

Barth’s ménage à trois was an embarrassment to all parties involved and to those connected to them. His mistress’ name was Charlotte von Kirschbaum (1899-1975). In chapter nine, Tietz publicizes material that Karl Barth did not want to be a part of his literary estate, since it could be subsequently made available for public consumption. This part of his life he definitely wanted to keep secret, given how selfish and inconsiderate he was. The picture that emerges of Charlotte moving into the residence with Nelly and the kids is agonizing to read (see also pp.214-219). Surprisingly, Nelly, albeit grief-stricken, came to terms with it and began to see the three-way union as an arrangement that was favored by God (p.216).

Barth opposed National Socialism. Indeed, he refused to take the oath of loyalty to Hitler in which the confessor must say ‘I swear that I will be loyal and obedient to the leader of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, obey the laws and fulfil my official duties conscientiously, so help me God.’ Barth, accordingly, was dismissed from his professorship at Bonn, was banned from speaking throughout the country, and so he went to Basel. There were Lutheran pastors who opposed him on this issue. He refused to budge. When the war ended, he supposed that some intellectuals needed to face up to their culpability, even their guilt, in order to make genuine forgiveness a reality. Several chapters cover the politics of the period.

An entire chapter in KBLC is assigned to describing the Church Dogmatics (CD). Tietz’ familiarity with Barth’s theology is evenly displayed. CD Volumes were composed over a three-decade period. An able writer, Barth was capable of saying many things at once in one sentence. This skill was also a defect for a theological tradition that prided itself on literary precision. There were to be five parts: Part I: The Doctrine of the Word of God; Part II: The Doctrine of God; Part III: The Doctrine of Creation; Part IV The Doctrine of Reconciliation, and Part V: The Doctrine of Redemption. Part IV was not finished, and Part V was never begun. It was nicknamed ‘The White Whale’ or ‘Moby Dick’ (p.362).

Though often accused of Catholic leanings, Barth acknowledged being Protestant in his orientation. His proprieties and convictions in scholarship situated him far from the center of, even outside of, mainstream orthodoxy. By instituting new categories for theological reflection, his originality converted multitudes and intensified his followers’ faith in this new system of divinity.

The CD volumes that did appear were thick, written in small print with much of it in smaller Brevier. When his phrases are scanned closely it becomes obvious why he was repeatedly accused of equivocation. What he gives the reader in one sentence is taken back in the sentences that follow. He sees no dilemma in choosing opposing views and siding with each. Even still, to be unequally yoked to irreconcilable views was a painful way to pull a massive but theological agenda like his. Expressions of his about man’s depravity are weak and slanted toward tendencies of the goodness of man. He was accused of being a universalist because of his broadmindedness on the issue of the guilt of Adam and the extent of the atonement. His prevarications on the word of God can be noted down as propositions.

Tietz (p.364f) writes,

(1) ‘Barth made it clear that ultimately ONLY God could speak properly about God’. However, he affirmed the necessity of (2) ‘the preached Word of God proclaimed in the sermon’. Further on he says that the Bible (3) ‘witnesses to God’s revelation, but that does NOT mean that God’s revelation is now before us in any kind of divine revealedness’ [Caps mine].

According to Barth, only God can define his attributes or express his perfections correctly. Human vessels who strive to proclaim the word are inept or too deficient to do so; still he wants readers to assume he believes there is a ‘written Word of God in the Bible’ and that ‘Jesus is the revealed Word of God’. Barth is not quite sure though which inscribed words are inspired or what the term inspiration means. Therefore careful dialectal investigations are required to make informed decisions or advances in our knowledge. Besides, seeing that he declared the biblical words now in the hands of men lack divine authority and are not a divine revelation, one can see clearly that cynicism controlled the construction of his thoughts. Holding this point of view he stood in total contradiction of how figures in scripture, like Old Testament prophets and New Testament apostles, envisioned their callings and functions as ‘inspired’ witnesses of God that were sent to Israel and to the nations.

Barth’s final years were spent in travel abroad, and regularly in hospitals because of his various illnesses. Because of her infirmity, too, Charlotte moved out of the family home and into a psychiatric clinic (p.391). He wrote shorter articles, cultivated friendships. He died in the night on December 10, 1968. And on December 14, 1968, an overfilled Basel Munster Church hosted Barth’s memorial service, which was broadcast live on the radio (p.401).

Criticism of Barth

A large index appends the CD. It forms a chain to roughly 15,000 scriptural references. It is a helpful work. Barth’s way of argument, however, rarely drew attention to core meanings of Greek or Hebrew lexemes in their original texts and contexts. For all the proficiencies he exhibited, he failed to deploy tools of philology with exactitude. His manner of debate was philosophical. Essentially, his assertions were carefully crafted non-sense statements that appeared to bridge the gap between conservatism and modernism but were often bridges to no-where in particular. Many of his ruminations were incredulous and fostered no comfortable assurances for those who zealously preserved liturgical traditions, while at the same time disavowing orthodox faith in any personal God that was typified by religious symbols used in their liturgy.

Of the mixture of theological approaches extant in the Germany of the 1930s, Barth’s was in the ascendant. Protestant and Roman Catholic alike sought to sit at his feet. Was Karl really an ecumenical figure? Maybe. More than one institution presently is devoted to the study of literature by and about Barth. However, hardly any of the scholars working in these ‘Centres’, or presenting at various Barth conferences, can agree on what Barth’s idiom originally meant in German, much less on the best way to express that meaning in other languages. It is an interesting legacy for enthusiasts to perpetuate.

Karl Barth’s creative interpretations in Church Dogmatics revealed his [mis]understanding of exegetical traditions of the Reformation. Through his efforts, however, he ploughed up old, hidebound Calvinistic traditions and planted new seeds whose growth sprouted up as a Neo-Reformed[i] movement of sorts, all founded upon his systematic theology. Friend and foe now stand on either side of the field loudly voicing to one another their agreements, praises, opinions, and complaints.

Criticism of the KBLC

Disagreement often surfaces when Barth’s name is brought up. Mystification persists wherever he is the topic of scholarly investigation or whenever an attempt is made to explicate his reasonings. This book does not conceal the tensions and conflicts of Barth’s life or his occasionally belligerent moods. But with the hindsight of half a century, the author should have done more for twenty-first century readers. As an adept Barth scholar, Tietz should have interspersed objective valuations of him or composed a final chapter of critical appraisals of Barth, the man and scholar. A set of brief appendices addressing his peculiar modes of thought and his scholarly pursuits would have increased the value of KBLC. More than 200 pages treat of 1921-1944. Disproportionately, less than 90 pages cover his life from 1945 to 1968.

The volume lacks the kind of engagement with Barth’s scholarship that one finds in Konrad Hamman, Rudolf Bultmann: A Biography (2013). Solid impressions about Barth’s political attitudes are given. Measured scholarly analyses of his system of divinity go unchecked in Tietz’ contribution to Barthian research. I was left with many questions about his verbal techniques in the classroom exegesis of biblical books and wanted much more comprehensive data on the origins of many of his historical books. Honors piled up on him. In the end the feeling one gets from reading this book is that Barth’s theology was the truest of his era and was omnipresently lauded, that voices in opposition to him were of a minor character.

KBLC stands as a first-rate piece of research and is a great supplement to Busch’s work. But despite all the recently released material now gathered in this new volume, and cited with the myriads of footnotes, it in no way supersedes Busch. Tietz is narrative biography at is best, tilted toward a commemorative form; but it is in no wise critical, if by ‘critical’ one is referring to the kind of studies done in classical and ancient near eastern disciplines.

The three-page Epilogue is disappointing. Tietz tells us that ‘in the German-speaking world there has been an extensive turning away from Barth’s theology’ (p.410). She does not give reasons for this present-day snub. Yet, being thoroughly unacquainted with the American church scene, she argues that in America [also in Great Britain and Asia] ‘Barth remains one of the most frequently read theologians’. Actually, vis-à-vis the USA, this assertion is dubious.

On the other hand, even today Barth has professional and amateur readers studying him. The small clique of specialized scholars who still investigate his books, articles and letters for nuances that ring true in modern ears have little or no influence on any growing denominations or evangelistic fellowships with large congregations. Indeed publications on him in colleges, universities and seminaries routinely are composed by erudite men and women who write for a readership that consists of the same handfuls of souls who conduct research on some aspect of his work or attended an annual Barth conference. Afterwards, those attendees plead incessantly that the speaker’s lecture notes (ones which they heard), be revised, edited, and advertised. All in all, awareness of the subject has been raised, but the evolvement is circular all the way through.

Publications in the Bibliography highlight Tietz’ progressive framework. Barth himself gave little attention to English language theological works. As a result, the critical evaluations of Barth’s scholarship appearing in KBLC misrepresent the Reformed views acknowledged within greater academia from 1919-1968. This fact is true especially since Tietz does not contrast Barth’s views with the traditional theological norms propagated by Fundamentalist, Evangelical and Calvinistic scholars, which he sought to overturn.

KBLC is well bound. Pictures throughout are clear. Pages are a bright, white but the texture is of low quality. The slightest moisture has an undesirable effect on the pages.

[i] Neo-Orthodoxy is the theological movement in contemporary Protestantism which seeks to correct both liberalism and the orthodoxy against which liberalism rightly protested, by a return to, and contemporary re-interpretation of the fundamental and formative significance of the Bible in the sixteenth century Reformers, chiefly of Luther and Calvin, in Theology Today, Vol. XIII, No.3 (1956), 336. For Barth’s 70th birthday, the Theological Seminary of Princeton held a colloquium regarding Barth’s work and his influence on various scholars. Aside from G.S. Hendry’s submission, ‘The Dogmatic Form of Barth’s Theology’, the published results of the seminar was an exercise in hagiography.

Pastor Darrell Sutton is a regular contributor to QR