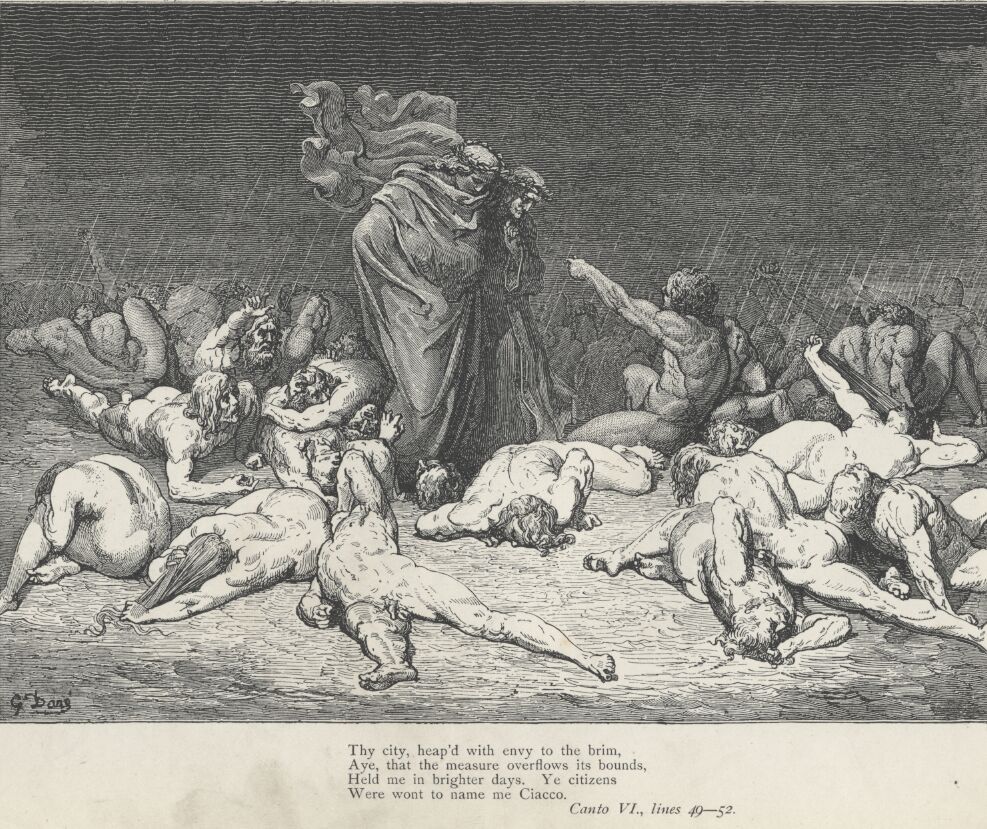

Doré, Inferno, credit Wikipedia

Mendicant Order

by Bill Hartley

There is a large restaurant in Leeds city centre and at the side of the building is a fire escape. The doors to the fire escape are blocked and given the prominent location it might be assumed that this would attract the attention of the Fire Service. After all there are penalties for blocking fire escapes.

In fact the Fire Service is aware of the situation but chooses to do nothing. The blockage consists of a tent; one of those igloo type designs commonly seen at Everest base camp. It is occupied periodically by a ‘homeless person’. A police officer who patrols the district is acquainted with this middle aged male and says he has been offered accommodation but prefers life on the streets. The officer would like to remove the tent but is forbidden from doing so because it is occupied and its removal would contravene local policy. In fact, there are various agencies in Leeds who prefer to play pass the parcel, even to the extent of ignoring a breach in fire regulations.

The sight of people begging on the streets, particularly in our larger cities, is common these days. Begging is of course illegal but it goes on and how it is dealt with varies from place to place. There is a tendency to hang the label of ‘homeless’ on those seen begging. As we shall see there are many beggars who take advantage of this. Like the man blocking the fire escape homelessness may be hard to define and officialdom finds it convenient to roll all street people into the same bundle to become a problem which is being ‘managed’.

In February 2018, in Torquay, the BBC covered a story about a local businessman who was ‘photo-shaming’ fake homeless people in the town. The one thing officialdom don’t like is any show of initiative from the public and this drew a predictable response from local police who claimed that it encouraged vigilantism, though they didn’t explain how. The businessman incidentally was also running a scheme to help the genuinely homeless and a spokeswoman from a local charity, Humanity Torbay, said that whilst they didn’t believe in naming and shaming, ‘the genuinely homeless can go down the end of town without fear of reprisals’.

Another BBC report from 2019 included an interview with a homeless person on the streets of Liverpool. He told the reporter that in his estimation there were only eight genuinely homeless people in the city centre that evening and graphically went on to illustrate how it’s possible to tell the difference. His haggard features and scarred hands he explained showed the effect of three years living on the streets. When asked why he didn’t take up the offer of hostel accommodation he was equally blunt. ‘I don’t want to share a space with aggressive drunks and drug users, would you?’

Leeds has undergone a transformation in recent years with many more people living in the city centre. Former warehouses along the River Aire have been converted into flats and these in turn sit alongside newer developments, creating a vibrant townscape. Inevitably there are genuine homeless people in the city centre, some of whom seem to prefer this life due to a drug habit or perhaps because they have lost the ability to coexist with others. However as that man in Liverpool told the BBC reporter, the homeless have been joined by those who see begging as an easy way to make money. This is a view supported by people who manage buildings in Leeds city centre. They tend to be on duty round the clock and report seeing taxis arriving, carrying beggars with their blankets, ready to set up shop for the day.

The modern practice is for joint working amongst the various agencies which have an interest in street people. This approach has long been encouraged by central government who used to criticise departments for failing to do joined up working where their interests overlapped. However at local level there is a strong impression that the joint approach gives individual agencies an excuse for not using their own powers of enforcement, because they have subsumed themselves into a ‘strategy’. It is unlikely though that within this strategy will be any determination to actually solve the problem.

Joint working sounds fine in theory but as anyone with experience of it might attest, it calls for strong leadership and a willingness by individuals to take responsibility. In practise there are vested interests, inter departmental rivalries and above all no precise accountability. However the benefit for the authorities is that the public, who might complain about beggars, can be told the authorities are aware and the problem is being managed. Try asking Leeds City Council street wardens how it is being managed. They report anti-social (begging) activity to the police who don’t want to know. The police it seems will only act in concert with the ‘Street Liaison Team’ whose job it is to approach these people.

An alternative might be to identify the genuinely homeless and work with them. To give such people confidence to come off the streets there needs to be the provision of hostel accommodation which is robustly managed and therefore a safe place to be. The scale of the problem might then be reduced by enforcing the law against those who leave their homes in order to come into a city centre to beg. However, for people doing the joined up working approach it’s not as simple as that. Street people are considered to have ‘complex needs’, which is a nicely sanitised phrase for describing those who beg in order to fund a drink or drug habit. The Leeds City Council website states that for nearly a decade they have been running an outreach programme for street people. It doesn’t mention any progress having been made. The outreach team report lots of interventions, but nothing is said about completions. ‘Complex needs’ are again cited and the website reports that the team are now ‘convinced’ that they need specialised help. In short, the team would prefer to expand its numbers unsupported by any evidence of success.

The Yorkshire Evening Post has reported cases of fights between beggars wishing to secure the best pitches (often next to an ATM). A senior police officer has been quoted as saying ‘it is vital that we take a balanced and coordinated approach and our priority is always the well-being of the individual concerned’. Evidently it is not quite so vital to look after the needs of the paying public and address the decline in economic activity as shoppers go elsewhere. In 2016, the paper reported that a man called Richard Scott was taken to court for breaching a dispersal order. The paper noted that he wasn’t homeless and received benefits. Since then things haven’t changed much. In 2017 Leeds Live reported that David Braithwaite was caught begging. Mr Braithwaite seems to have started his career in 2013 and was ‘spoken to’ 35 times before being taken to court. He chose to ignore offers of ‘help’ although being in receipt of housing benefit, employment and support allowances; it would seem he was getting the same as anyone else. A police chief inspector and a member of the city’s Community Safety Partnership practically apologised for enforcing the law, referring to the ‘well balanced approach’ and how ‘enforcement is always the last resort’.

The problem of street people has become institutionalised. Leeds City Council has apportioned a budget and for those involved there are jobs and a career path. Well behind this last resort approach is any consideration for those who live, work and shop in the city centre. It seems there is no will to use the powers available, or indeed to find a solution.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Like this:

Like Loading...

Mendicant Order

Doré, Inferno, credit Wikipedia

Mendicant Order

by Bill Hartley

There is a large restaurant in Leeds city centre and at the side of the building is a fire escape. The doors to the fire escape are blocked and given the prominent location it might be assumed that this would attract the attention of the Fire Service. After all there are penalties for blocking fire escapes.

In fact the Fire Service is aware of the situation but chooses to do nothing. The blockage consists of a tent; one of those igloo type designs commonly seen at Everest base camp. It is occupied periodically by a ‘homeless person’. A police officer who patrols the district is acquainted with this middle aged male and says he has been offered accommodation but prefers life on the streets. The officer would like to remove the tent but is forbidden from doing so because it is occupied and its removal would contravene local policy. In fact, there are various agencies in Leeds who prefer to play pass the parcel, even to the extent of ignoring a breach in fire regulations.

The sight of people begging on the streets, particularly in our larger cities, is common these days. Begging is of course illegal but it goes on and how it is dealt with varies from place to place. There is a tendency to hang the label of ‘homeless’ on those seen begging. As we shall see there are many beggars who take advantage of this. Like the man blocking the fire escape homelessness may be hard to define and officialdom finds it convenient to roll all street people into the same bundle to become a problem which is being ‘managed’.

In February 2018, in Torquay, the BBC covered a story about a local businessman who was ‘photo-shaming’ fake homeless people in the town. The one thing officialdom don’t like is any show of initiative from the public and this drew a predictable response from local police who claimed that it encouraged vigilantism, though they didn’t explain how. The businessman incidentally was also running a scheme to help the genuinely homeless and a spokeswoman from a local charity, Humanity Torbay, said that whilst they didn’t believe in naming and shaming, ‘the genuinely homeless can go down the end of town without fear of reprisals’.

Another BBC report from 2019 included an interview with a homeless person on the streets of Liverpool. He told the reporter that in his estimation there were only eight genuinely homeless people in the city centre that evening and graphically went on to illustrate how it’s possible to tell the difference. His haggard features and scarred hands he explained showed the effect of three years living on the streets. When asked why he didn’t take up the offer of hostel accommodation he was equally blunt. ‘I don’t want to share a space with aggressive drunks and drug users, would you?’

Leeds has undergone a transformation in recent years with many more people living in the city centre. Former warehouses along the River Aire have been converted into flats and these in turn sit alongside newer developments, creating a vibrant townscape. Inevitably there are genuine homeless people in the city centre, some of whom seem to prefer this life due to a drug habit or perhaps because they have lost the ability to coexist with others. However as that man in Liverpool told the BBC reporter, the homeless have been joined by those who see begging as an easy way to make money. This is a view supported by people who manage buildings in Leeds city centre. They tend to be on duty round the clock and report seeing taxis arriving, carrying beggars with their blankets, ready to set up shop for the day.

The modern practice is for joint working amongst the various agencies which have an interest in street people. This approach has long been encouraged by central government who used to criticise departments for failing to do joined up working where their interests overlapped. However at local level there is a strong impression that the joint approach gives individual agencies an excuse for not using their own powers of enforcement, because they have subsumed themselves into a ‘strategy’. It is unlikely though that within this strategy will be any determination to actually solve the problem.

Joint working sounds fine in theory but as anyone with experience of it might attest, it calls for strong leadership and a willingness by individuals to take responsibility. In practise there are vested interests, inter departmental rivalries and above all no precise accountability. However the benefit for the authorities is that the public, who might complain about beggars, can be told the authorities are aware and the problem is being managed. Try asking Leeds City Council street wardens how it is being managed. They report anti-social (begging) activity to the police who don’t want to know. The police it seems will only act in concert with the ‘Street Liaison Team’ whose job it is to approach these people.

An alternative might be to identify the genuinely homeless and work with them. To give such people confidence to come off the streets there needs to be the provision of hostel accommodation which is robustly managed and therefore a safe place to be. The scale of the problem might then be reduced by enforcing the law against those who leave their homes in order to come into a city centre to beg. However, for people doing the joined up working approach it’s not as simple as that. Street people are considered to have ‘complex needs’, which is a nicely sanitised phrase for describing those who beg in order to fund a drink or drug habit. The Leeds City Council website states that for nearly a decade they have been running an outreach programme for street people. It doesn’t mention any progress having been made. The outreach team report lots of interventions, but nothing is said about completions. ‘Complex needs’ are again cited and the website reports that the team are now ‘convinced’ that they need specialised help. In short, the team would prefer to expand its numbers unsupported by any evidence of success.

The Yorkshire Evening Post has reported cases of fights between beggars wishing to secure the best pitches (often next to an ATM). A senior police officer has been quoted as saying ‘it is vital that we take a balanced and coordinated approach and our priority is always the well-being of the individual concerned’. Evidently it is not quite so vital to look after the needs of the paying public and address the decline in economic activity as shoppers go elsewhere. In 2016, the paper reported that a man called Richard Scott was taken to court for breaching a dispersal order. The paper noted that he wasn’t homeless and received benefits. Since then things haven’t changed much. In 2017 Leeds Live reported that David Braithwaite was caught begging. Mr Braithwaite seems to have started his career in 2013 and was ‘spoken to’ 35 times before being taken to court. He chose to ignore offers of ‘help’ although being in receipt of housing benefit, employment and support allowances; it would seem he was getting the same as anyone else. A police chief inspector and a member of the city’s Community Safety Partnership practically apologised for enforcing the law, referring to the ‘well balanced approach’ and how ‘enforcement is always the last resort’.

The problem of street people has become institutionalised. Leeds City Council has apportioned a budget and for those involved there are jobs and a career path. Well behind this last resort approach is any consideration for those who live, work and shop in the city centre. It seems there is no will to use the powers available, or indeed to find a solution.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Share this:

Like this: