Jan van Leiden tauft ein Mädchen

Mad Days in Münster

Le prophète, Grand Opera in 5 acts composed by Giacomo Meyerbeer, Deutsche Oper, Berlin, November 26th, 2017, directed by Olivier Py, conducted by Enrique Mazzola, reviewed by TONY COOPER

Le prophète forms part of a project that has seen new productions at Deutsche Oper Berlin of Les Huguenots (2012) and Vasco da Gama (L’Africaine) (2015) while a concertante version of Meyerbeer’s opéra comique, Dinorah, formally entitled Le pardon de Ploërmel, was staged in 2014.

It charts the rise and fall of the rebellious Protestant Anabaptists who tried to establish a communal sectarian government in the Westphalian city of Münster during the Reformation. The city, in fact, came under their direct rule from February 1534 – when the city-hall was seized and Bernhard Knipperdolling installed as mayor – until its fall in June 1535. It was Melchior Hoffman who initiated adult baptism in Strasbourg in 1530, and his line of eschatological Anabaptism helped lay the foundations for the dramatic events in Münster, one of the bloodiest chapters in the history of the Reformation.

Meyerbeer’s opera Le prophète captured this slice of history convincingly and was frequently performed on the world’s leading opera stages. But, sadly, it fell completely out of favour in the early part of the 20th century and only slowly recovered its status with revivals at Zürich Opera in 1962 and Deutsche Oper Berlin in 1966 (both featuring Sandra Warfield and James McCracken in the leading roles). A revival at The Met in 1977 starred Marilyn Horne as Fidès. Vienna State Opera also brought it to the stage in 1998 in a production directed by Hans Neuenfels with Plácido Domingo and Agnes Baltsa. Happily, over the past few years, Le prophète is finding its feet once more in European houses.

Sung in French to a libretto by Eugène Scribe and Émile Deschamps, after passages from the Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations by Voltaire, the scenario concerns the self-proclaimed ‘King of Münster’ and Anabaptist leader, Jean de Leyden, who leads a band of fundamentalists in an act of defiance against the despotic Catholic authorities but soon realises that the revolutionaries are as corrupt as the rulers they have displaced. Le prophète has lost none of its political relevance in the present century.

Yet within the grandiose framework of this historical drama, Le prophète is also a psychological battle between mother and son. The real adversary of Jean de Leyden is his mother, Fidès, a strong, forthright and determined woman who could have jumped out of the pages of Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba. She spares no effort to re-establish her own control over her apostate son. It is a conflict that pervades the entire work right up to its bitter (and dramatic) end.

American tenor, Gregory Kunde – an exciting singer with a richly-textured voice making his role début as Jean de Leyden – put in a commanding and exhilarating performance in this strenuous and demanding part, as did the Russian soprano, Elena Tsallagova, as his lover, Berthe. But in true 19th-century operatic style she’s coveted by another – in this case Count Oberthal, ruler of Dordrecht, sung (and acted) in a suave and arrogant manner by Berlin-based bass-baritone, Seth Carico.

French mezzo-soprano, Clémentine Margaine – based at Deutsche Oper Berlin originally as a stipendiary and later as a member of the ensemble from 2011 to 2014 – made her role début as Fidès and thoroughly stamped her credentials on what is another taxing part. Her distinctive voice radiated effortlessly around Deutsche Oper’s vast auditorium.

One unforgettable scene featured Clémentine Margain and Elena Tsallagova in the duet ‘Pour garder à, ton film le serment’ in in Act II, concerning the fate of Jean and his whereabouts. Passionately and convincingly sung, it gave way to a thrilling trio in the same act – ‘Loin de la ville’- with both singers joining Gregory Kunde as they dreamed of bliss and happiness and their future life together. But dreams rarely come true in 19th-century opera.

The musical continuity of the work is engaging, too, and a host of recurring themes underlie it. The principal theme, the Anabaptist hymn – ‘Ad nos, ad salutarem undam, iterum venite miseri’ – heard to good effect in Act I, reappears in Act III when Jean calms his troops having just suffered a massive defeat. The theme returns once more at the beginning of the final act as the three Anabaptists – admirably led by Taiwanese tenor, Ya-Chung Huang – plot to betray their ‘Prophet’.

Another recurring motif relates to the role of the ‘Prophet’ and is dramatically heard in a distorted form in Act II when Jean recounts the dream that haunts him and is repeated, but with a very different tone and rhythm, in the Coronation March of Act IV during which the crown, the sceptre and the sword of justice and the seal of State are handed over to him. The Coronation ends spectacularly with a large crowd heaping praises on the ‘Prophet’ for the miracles he has accomplished (in this production he is seen healing the blind and the disabled) while acclaiming him the Son of God.

This was 19th-century grand opera in every sense with the Deutsche Oper stage taken up by a choruses over 80 strong, without taking into account the children’s chorus. The orchestra, under the baton of Enrique Mazzola, captured the essence and splendour of Meyerbeer’s exciting score.

But in such a serious opera as this comedy found its place, too, with the trio in act III, notable for the original way in which a grave situation is set by Meyerbeer complemented by a comic situation, and which focuses on Count Oberthal arriving under the cover of darkness to the Anabaptist camp hoping to infiltrate their group and disrupt their plans. In the trio that follows Oberthal swears, to a jovial-sounding tune – ‘Sous votre bannière que faudra-t-il faire?’ – that he’s ready to execute as many aristocrats as he can while the Anabaptists, Zaccharias and Jonas – sung immaculately by Derek Welton and Andrew Dickinson – cheekily complement his actions. It’s not until Jonas holds a lamp to Oberthal’s face that he recognises his enemy whereby the two Anabaptists swear to kill him while Oberthal, in turn, expresses his hatred of them.

More often than not ballet proved a popular divertissement in 19th-century opera and in the first scene of act III, the ballet music of Les Patineurs is featured in which the dancers mimic ice-skaters. But in this production it was different as the dancers were seen on a massive revolving stage engaged in some telling and imaginative choreography, created by Olivier Py, centred round a war-torn, high-rise block of flats. Matthew Bourne, I’m sure, would have been impressed.

The director eschewed the traditional framework of farmsteads and windmills, turning the peasants into white- and blue-collar workers, the occupants of high-rise flats. Sporting Trilby hats, the men were smartly dressed in two-piece suits and ties while the women were turned out in nicely-patterned day-to-day dresses created by costume designer, Pierre-André Weitz.

The farmstead seemed far away. And the farm-horse, too, witness Count Oberthal arriving on the scene in a smart chromium-trimmed black Mercedes-Benz looking like a playboy and shadowed by a coterie of henchmen with single-barrelled repeating shotguns at the ready, mirroring Frank Castorf’s Bayreuth bicentennial Ring cycle.

The musical and theatrical influences of Le prophète – so much admired by Berlioz who attended its Paris première – include Liszt’s monumental Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale ‘Ad nos, ad salutarem undam’ for organ, based on the Anabaptists’ hymn and, indeed, dedicated to Meyerbeer and also the duet between mother and lost child in Verdi’s Il trovatore. And the finale of Le prophète – culminating in fire, destruction and death – closely mirrors the catastrophic finale of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung.

The tremendous success of Le prophète provoked an anti-Jewish attack on Meyerbeer by Wagner who in his essay Das Judenthum in der Musik also targeted Mendelssohn. Published under a pseudonym in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik of Leipzig in September 1850, it was reissued in a greatly expanded version under Wagner’s name in 1869. It is regarded by many commentators as an important landmark in the history of German anti-Semitism.

This was a serious and grand affair with no expense spared but to get such a large production onto the stage does not come cheap and the German government stepped in with monies set aside by the Bundestag to mark the 500th anniversary of The Reformation. It is a landmark year for Germany and this production of Le prophète will proudly takes in place in its history.

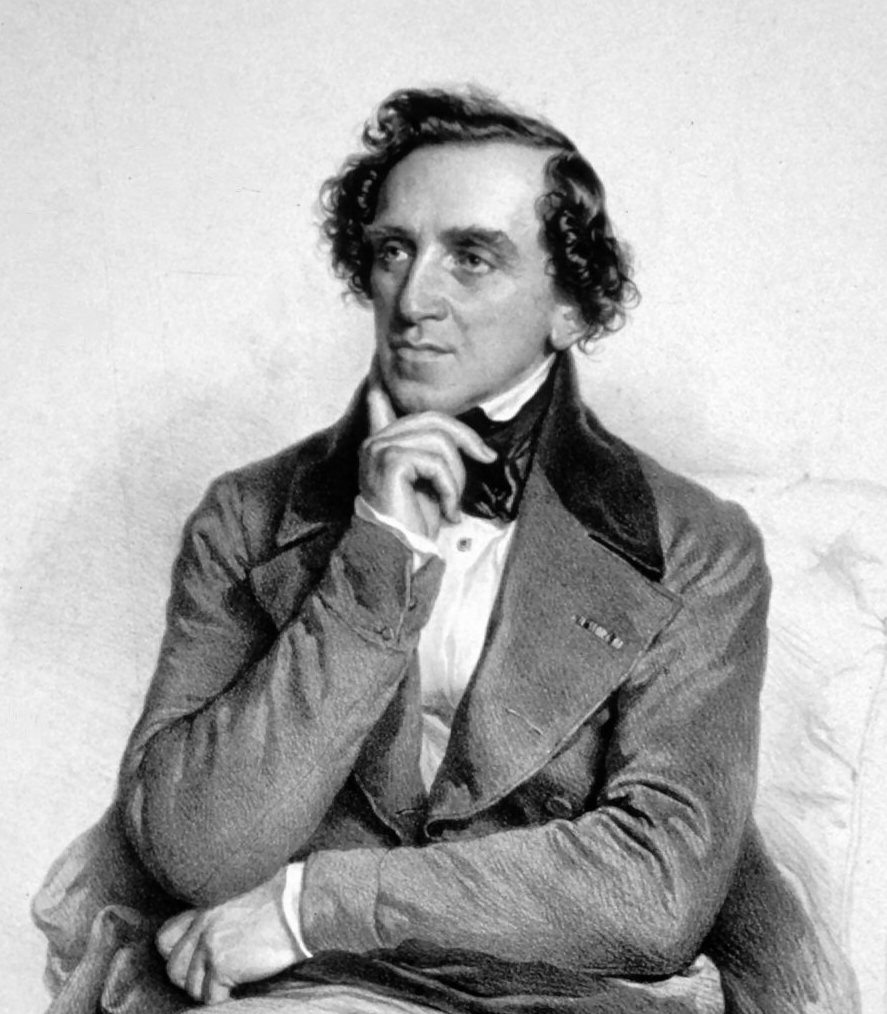

Giacomo Meyerbeer

Tony Cooper is QR’s opera critic

Very interesting. Sounds like Fides owes something to Volumnia in Coriolanus. Is there anything in this?