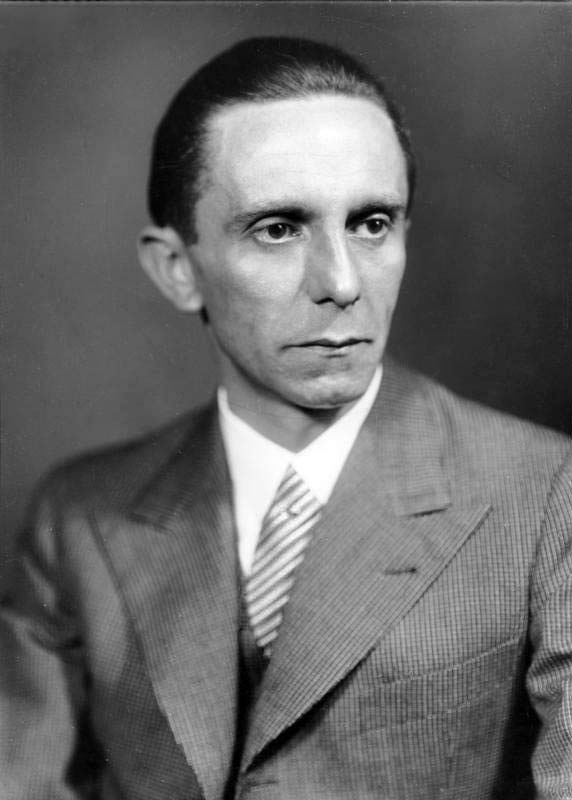

Joseph Goebbels, Bundesarchiv_Bild

Joseph Goebbels, Chronicler of a Catastrophe

Stoddard Martin transcends the tyranny of fact

There are possible revelations to be inferred from Peter Longerich’s exhaustive biography of Joseph Goebbels, but when I started out on his long, rich account I had to ask myself why I was going over this terrible history once again. When, I wondered, is the world going to tire of fascination with the Nazis? In answer came the rhetorical questions: when will little boys give up asking daddy to play scary baboon? When will teenaged girls cease to titter about the antics of rogue males? When will policy wonks on ‘national security’ sofas stop being swayed by the most audacious voice among them?

The most audacious voice among Nazi jostlers for power was often and finally that of club-footed, simian, non-Aryan looking Goebbels. Unlikely you may think next to blue-eyed Rudolf Hess or ‘matinee idol’ World War I hero Hermann Göring. But the Chaplinesque little Rhinelander had drive – call it need to prove himself, if you wish, or ‘narcissistic personality’, if you need to resort to the day-before-yesterday’s psychobabble. Longerich protects himself with this lingo on occasion.[i] Yet while armchair analysts may enjoy speculating about motivation, historians must deal in known acts. For them the question may be not so much why as how did he do it?

Energy is an answer. Hess decamped early; Göring grew drug-ridden, indolent; Hitler withdrew into indecision, even invisibility, as National Socialism’s triumphs morphed into disaster. Goebbels, a radical and fighter by nature, angled and manoeuvred against rivals early and late – the Strassers as left leaders, Rosenberg as ideologue – to dominate an agenda, becoming Reich Plenipotentiary in the last year of ‘total war’. His main backing, Longerich makes clear, came always from Hitler. Quid pro quo was Goebbels’s expression of faith in a Führer prinzip. The Reich’s minister for propaganda never deviated from this in public. In private the profession often may have been tortuous.

We know this courtesy of diaries Goebbels kept throughout his Nazi years. They are an ultimate product of his early ambition to be a writer. Avid reader in youth – favorites included Hamsun and Hesse, as well as Dostoyevsky – young Joseph gained a doctorate in literature and laboured through his twenties to make himself a leading voice of the Weimar decade. A lower middle class provincial who deprecated the era’s establishment, he was not well-placed to achieve it; his Bildungsroman Michael Voormann was disregarded, and two plays of his were performed only perfunctorily in Party-backed theatres. Eventually, like Hitler diverting his ambition as artist to other ends, the writer-manqué found his niche in a new brand of rhetoric. He became warm-up act for the Führer as Party speech-maker and, when Hitler descended to near silence towards the end, virtual voice of the Reich. Simultaneously he came to make Clintonian sums from book-writing and journalism[ii].

Longerich leans heavily on Goebbels’ diaries to tell his tale, buttressing well-known passages with new material unearthed in the past decade as well as deconstruction of subtext. Posterity may ever have to rely on these diaries for its most substantial insider view of a terrible regime, but the propagandist was always a spinner of fact and as time went on increasingly sensitive to how truth had to be massaged or even kept from his audience, sometimes possibly even from himself or at least the secretaries to whom he dictated. Reader, beware. One must also bear in mind that, despite occasional quotation from Nietzsche, the little doctor was no superman. Subject to skin disease, kidney disorders, bouts of melancholy or depression, he was in such weakness not so different from Hitler, Göring and others of the regime’s surprisingly fragile bosses. He does, however, seem to have exceeded them in capacity for rallying against downturn, profiting possibly from his own diatribes to the Volk about need for maintaining morale – if not in ‘mood’, then at least in ‘bearing’[iii].

To a considerable degree Goebbels was able to believe his own bullshit. Yet the strongest streak in his nature appears to have been a kind of sado-masochistic pragmatism. In periods when Nazi dogma failed to cohere, such as the ‘socialist’ vs conservative arguments of ‘the years of struggle’, he glommed onto anti-Semitism as a handy glue – this despite having a half-Jewish girlfriend for years, being himself considered a ‘Jewish’ type by some[iv] and rarely harboring racist views during his school or university days. The sadistic dogma would return with vengeance as war began to shatter national fortunes and again operated as a kind of ideological glue, this time to bind the otherwise apparently opposed enemy identities of Western plutocracy and Bolshevism. Both were part of the ‘international Jewish conspiracy’, don’t you know? – Goebbels had read The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and, though sophisticated enough to accept that they were probably fake, maintained that they must in any case have been put together by authors who knew an essential truth.

The mass cruelty which derived from this attitude is well-known, also Goebbels’ role as cheerleader of it. The obverse – a masochistic aspect of his pragmatism – becomes clearer from Longerich’s book than it perhaps ever has been before. It centers on Goebbels’ marriage to Magda Quandt, grandmother to the present-day BMW clan via a son from her first marriage. An ambitious and apparently exacting seductress whose own Jewish connections (stepfather) remained in the shade, Magda married Goebbels in 1931 and over the next decade produced five further children, to all of whom she gave names beginning with ‘H’. All these children, eldest and youngest daughters notably[v], were doted on by a godfather/protector to the family at large, another ‘H’ – Adolf Hitler. About the presence of this ‘third party’ in the Goebbels’ marriage, Longerich provides copious detail. He does not indulge in what the detail invites: obvious speculations.

Hitler was infatuated with Magda from first meeting. She could hardly have been but flattered by the attention of this yet greater star, whom her principal suitor idolized and was dependent upon. Whatever may have transpired in early days, the three soon enough ‘came to an agreement’, and Hitler stood witness at the Goebbels’ wedding. The newlyweds’ domestic life soon became stormy: rows, goings and comings, makings-up, new pregnancies/babies, bigger houses, faster cars, more extensive holidays and expensive gifts. The ‘Boss’ doubtless in mind, Magda would chide Joseph to make more progress in Party hierarchy and prestige. And all the while, her households were visited by said Boss, announced or not, with or without full entourage. The Goebbelses would be summoned on sudden whim to the Führer’s eyrie on the Obersalzburg; Magda might be invited to stay on if Josef was called back to Berlin on Gau business. She was also known to spend the night at the Führer’s Chancellery in Berlin, companioning him until the wee hours after some reception or concert which she may have attended with him, Joseph being out of town on ministry affairs.

Goebbels Family with Hitler

Goebbels’ goings and comings were determined ultimately by Hitler. Whenever large marital issues arose, Magda would turn to him for advice, whereupon he would summon his reliable underling to broker a solution, Goebbels’ status implied in the balance. On one occasion when she was giving birth, Hitler appeared at Magda’s hospital bedside before the apparent father.[vi] After a subsequent birth, the apparent father expressed jubilation on seeing a ‘true Goebbels face’[vii]. Such details[viii] almost invite us to ask, if we haven’t already, what are we to make of this? Longerich does not go so far as to line up probable dates of conception with Magda’s visits to or from Hitler, but one is tempted to wonder why ever not? Might he fear giving offense to present-day Quandts? Is the world not ready for the possibility that Hitler as sexual being was not quite the eunuch of popular lore? Would it humanize him, glamorize him to discover that for years he was participant in a kind of menage à trois, cadging covert cinq à septs with a mistress and subjecting her husband to a half-willing, half-outraged cuckholdry? Did he perhaps even father one or two of her kids?

Such things are not unknown. Among fascist contemporaries with an artistic bent, consider Mussolini or Ezra Pound. Bourgeois cover may have been expected for the Volk, but bohemian arrangements had long been a norm for ‘genius’. Hitler’s idol Richard Wagner took as mistress the wife of his conductor Hans von Bülow, fathering two daughters by her before Bülow, who idolized Der Meister and needed his patronage, lost his complacency and decamped. Goebbels clearly suffered from Magda’s lack of connubial devotion, of mind, body or both; thus the rows, thus his retreat to solitary guest houses or private lairs on one or another of their estates, thus his eventual affair with the actress Lila Baarova and decision during the darkening days of 1938 to end his marriage. But he couldn’t. The Boss wouldn’t have it. Magda as ever scurried to him for protection, and Hitler, preoccupied with the Sudeten crisis and perhaps his own needs as well as requirement that top Party bonzos[ix] not to be seen as licentious or corrupt, summoned the little doctor and decreed that the status quo remain. Goebbels had to break off his affair with Baarova, she losing patronage of a lover who by then was calling most of the shots in cinema as well as other arts in the Reich.

Goebbels was disconsolate. He turned to others for advice, even Göring whom he had hitherto disparaged and despised[x]. Sympathy was offered, but reprieve was in nobody’s gift but the Führer’s, and he would not budge. Goebbels swallowed hard, then worked quickly to re-cement relations with his boss, including by heightening the anti-Semitic rhetoric leading to Kristallnacht. Magda later confessed to her Josef that she had had an affair with his state secretary, Karl Hanke, another confidant and sometime liaison between the Propaganda Ministry and the Chancellery. Goebbels expressed fury, but by now what he was telling his diaries may have become code or part fiction. Magda, it is known, had a history – adultery had been a reason for break-up with her first husband – and whether Hanke was truly her lover during her second marriage, a sole lover or mere cover for somebody else cannot be more than surmised from what Longerich tells us.

About her great protector/admirer, these are known facts. From the later ‘20s, Hitler had shared his Munich flat with his niece Geli Raubel, with whom it is assumed that he had or was having an affair.[xi] Geli clearly hero-worshipped a relation whose trajectory was becoming stratospheric; at the same time, some of Hitler’s mentors and backers may have taken a dim view of a connection close enough to suggest incest, or in any case that of a mature man with a suggestible girl hardly out of her teens. In due course Geli was found dead – suicide, it appeared: shot with Hitler’s pistol when he was out of town. Yet who knows? What had been whispered by whom into whose ear? that if he cared for his career, such an amorous adventure had to be off the menu? that if she truly cared for her ‘great man’, she had to clear off? Did Geli need telling? Did Hitler? Did either of them listen? What did the aspirant leader, ever an intriguer for power, tell himself? – Whatever, Hitler was left in evident grief: feelings of guilt perhaps (was the man capable of it?), but grief nonetheless. Goebbels witnessed it close-hand, Magda too – she was by then on the scene. Hitler’s place in their life began on this note and was ever after predicated on a notion of the poor soul’s isolation – his deprivation of family, his inability or time to find suitable partner. Nor was it long before he was expressing an idea that one in his position could not afford to be ‘married’ to anyone but the German people.

Is this to be taken at face value? Scabrous tales such as that Hitler had only one testicle are about as credible as that Napoleon was only 5 feet tall. (He was 5’6”, as Andrew Roberts has corrected for a happily-deceived Anglo audience.[xii]) There is no real reason to believe that in the sexual department the Führer was less a man than the next. He did, after all, ultimately marry Eva Braun, a younger woman again and by most accounts attractive. Are we to suppose that for the decade or more that separated Geli from Eva, he never felt an urge, nor, being the most powerful individual in the land, found means to satisfy it? If he were ‘married’ to the Volk and dared not risk their jealousy or ire by appearing with a rival, what better option that to indulge in a covert occasional affair with a married woman whom he fancied and whose husband was bound to indulge it? If this were the truth about him and Magda – and nothing Longerich tells us discourages the hypothesis – it would explain why Goebbels was obliged to accept his intrusions as ‘part of the family’, why Hitler would invite the family as one or in part to the Obersalzburg – a privilege not accorded to others, certainly not with such frequency – and why he was always involved in the Goebbels’ family finances and in all disputes which might threaten to ‘upset the apple cart’[xiii].

What did others know? There were apparently rumours, for which Magda’s alleged affair with Hanke could well have been used as cover. We don’t know exactly what Goebbels told Göring etc. when Hitler forbade him to leave Magda in ‘38, but his confidants were either high Party members or sufficiently dependent on the Führer’s favour to keep shtum. The further and more shocking questions raised – whether Goebbels’ unusually large number of children were all his, whether one or more of them may have been Hitler’s, whether this may explain the unusually fatherly attitude the latter took and the former’s rather Joseph-like backgrounding – seem crucial to understanding the core natures of two of the most earth-shaking individuals of 20th century history; and I am amazed that they have not been mooted before and are not now taken up by Longerich, despite all he has laid out. Would it not have been in character for Hitler to play manipulative God-the-father in this way, equally for the ultimately opportunistic, Führer-bound Goebbels to have abased himself into the requisite masking role? Sharper light on these matters may also illuminate any rationale we can concoct for what on a personal level may be one of the darkest of all dark crimes of the Nazis[xiv]: murder of all five of the children in question, eldest age 14, in the bunker in Berlin just after Hitler took Braun’s life and his own and before their mother and Goebbels dutifully followed suit.

What kind of mother performs such an act? What kind of father? When Goebbels told Hitler that Magda had decided the whole family would stay in Berlin with him until the end, the Führer replied that the sentiment was ‘admirable’ but he could not encourage the act. In a version of the tale of Solomon with two mothers, does this reveal who the true father was? the one who might at all cost want to save his innocents? In analogous cases I’ve mentioned – Wagner, Mussolini, Pound – the biological father kept watch for his illegitimate offspring, creating protection for them through his own life and beyond[xv]. Yet by the stage we have arrived at in this history, Hitler had, according to Goebbels, become ‘frail’[xvi] and in many respects a broken man, indecisive, less than willful. Might this explain why he let himself be overruled by a ‘father’ only too eager to prevent the children from surviving into a world bereft of the ideology and regime in which he still posed fervid faith. Goebbels left a testament to the effect that the children, had they been old enough to choose, would have opted for death. So Magda and he chose for them, flattering themselves that they were joining an auto-da-fé that would inspire future generations, symbolic of the undying commitment of the best of their kind. In truth it testifies to a wanton cruelty that not even cornered a simian might resort to.

Why do we continue to pay attention to the Nazis? Humans can be the most perverted of beasts. And evil, alas, is ever fascinating – especially for the cossetted and the immature who have never been seriously threatened by it.

Goebbels: A Biography, by Peter Longerich, translated by Alan Bance, Jeremy Noakes and Lesley Sharpe (London: The Bodley Head, 2015), pp. 964. §30

ENDNOTES

[i] Longerich takes this up particularly in his ‘Prologue’, p. xv etc., and alludes to recent German studies of the matter in his bibliography and notes; but it is not really central to his text. One wonders if, as often in cases of commercial biographies from big name publishers, his nods to the matter aren’t the result of editorial suggestion after the digging, sifting and writing up of historical research had been completed

[ii] These were arranged for him with Hitler’s backing by Party publisher Max Amann. Whether for skill or by patronage, the writer-manqué thus became one of the highest-paid German-language authors of his day

[iii] Haltung in German, as Longerich points out in his impressive discussion of how skillfully Goebbels adapted language to the shifting requirements of persuading a reluctant people to continue a war which a majority of them – including the Propaganda Minister himself – had never supported with much optimism

[iv] Himmler’s wife, for example. See my essay on her correspondence with her husband in a previous QR

[v] At the birth of the first, when Goebbels expressed disappointment that it was only a girl, Hitler said he was ‘thrilled’ and called Magda ‘the loveliest, dearest, and cleverest of women’. When the child was six, he remarked that ‘if Helga was 20 years older and he was 20 years younger she would be the wife for him’. At the birth of the last child, he ‘shared in the family joy’ and on Magda’s birthday shortly after ‘suprisingly arrived in the afternoon to offer his congratulations’. Longerich, 189, 361, 473. Such details my seem unremarkable in themselves but as they accumulate begin to suggest much more than is said

[vi] This was at the birth of the second daughter. Longerich, 253

[vii] At the birth of the third child, a son. Longerich, 306

[viii] And there are more – such as that news of the birth of the fourth child, another daughter, reached Goebbels only via Hitler, to whom Magda had sent a telegram. Longerich, 380

[ix] German or Bavarian slang for ‘bosses’, thus the Tegernsee, where Himmler and others had houses, became known as ‘Lago di Bonzos’

[x] During the war, and especially as its fortunes deteriorated, Goebbels turned more and more to other top-Nazis to brainstorm policy and ‘help’ an overworked Führer, who was increasingly at the front and sequestered by military chiefs and their concerns. Göring was the nominal overseer of these discussions but Goebbels’ only really effective interlocutors, especially after the 20 July 1944 plot, were Himmler, Bormann and Speer

[xi] See Hitler and Geli by Ronald Hayman (Bloomsbury, 1997) for full discussion of this topic

[xii] In his recent biography Napoleon the Great (Allen Lane, 2014)

[xiii] Among plays Goebbels rated was G. B. Shaw’s The Apple Cart, which he saw in in January 1938. Both Goebbels and Hitler thought Shaw the greatest living playwright – ‘he lifts the veil from English hypocrisy’. They thought Shakespeare was the greatest of the dead, ‘towering above’ Schiller. Longerich, 354, 838

[xiv] Obviously on an historical level even such an egregious act is trivial compared to the Holocaust

[xv] Wagner’s children inherited ownership of their progenitor’s folly at Bayreuth, which remains one of Europe’s great cultural attractions to this day and is still run by his descendants. Pound’s daughter Mary de Rachewiltz, age 90, still presides over courses devoted to his work at Schloss Brunnenburg in the Italian Tyrol. Mussolini’s descendants have been active in Italian politics; Longerich (609) notes how Goebbels was ‘surprised’ when Hitler told him ‘for the first time’ in 1943 that Il Duce’s daughter Ella, married to his foreign minister Count Ciano, was brought up as if by his wife yet was in fact the love-child of his liaison with a Russian Jewess

[xvi] Shortly after the 1944 assassination attempt, Goebbels would say ‘”the Führer has gotten very old” and is making “a really frail impression”.’ (Longerich, 643.) By autumn of that year, Hitler had fallen ill with jaundice and perhaps worse. He more or less gave up speech-making, even on radio, despite the damage this threatened for the national mood. It is in this period that Goebbels became Reich Plenipotentiary. Hitler left a will at his suicide naming Goebbels his successor as Chancellor, but it of course was not to be.

Hitler lost the war, but “won” the peace – in terms of public obsession, screen ratings and print publications. People make history, and victors write it. Today, the sex lives, fact or fiction, of the “great men” are more interesting to feminized minds than their works, good or bad, and often advanced as a primary explanation for their thoughts and actions. Turning Charlie Chaplin into Satan is no problem for some, and making the lustful Schrumpfgermaner into a “simian” (!) cartoon character because of his curious relationship, personal/political, to his undersexed hypochondriac Leader, is even less a problem, especially for those who are reluctant to discuss, honestly and at length, his actual “bullshit” in e.g. “Das Reich”. Sarcasm and spite were his notorious psychological defence mechanisms, but he was certainly a skilled orator and movie organiser. Whether Longerich adds much of value to previous biographers like Thacker or The Man Who Must Never Be Read again (Berlin Irving) only scholarly historians with rare patience, obsession and erudition can perhaps judge. But whether an exact, albeit less unsympathetic, study of the Nazi leaders will ever be published, only time may tell -and probably never, as the world becomes irretrievably in almost every respect the precise opposite of what Hitler wanted, yet “achieved” by his own stubborn ruthlessness. Meanwhile, folks, drive along the scenic Autobahnen and admire the repaired Dresden, enjoy your Wagner, Bruckner and Orff, and read your Heidegger, Gehlen and Weinheber – while stocks last.