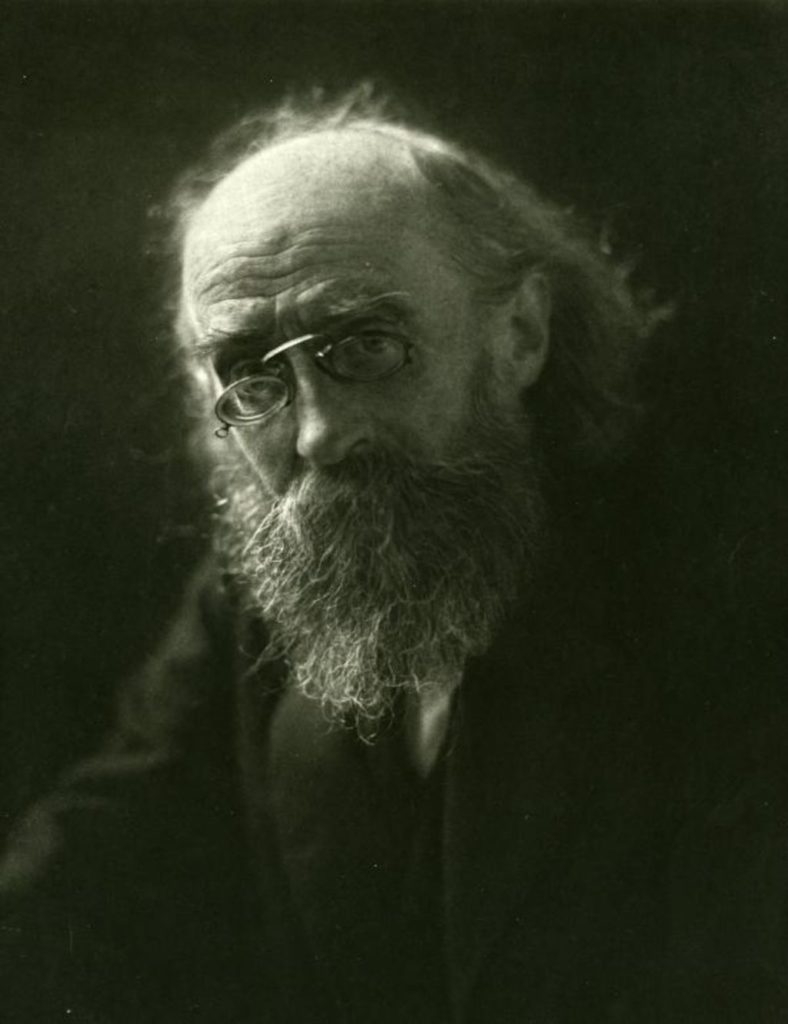

In Memoriam, George Parkin Grant,

1918-1988

By Mark Wegierski

George Parkin Grant (who usually called himself George Grant) is virtually unknown outside of Canada, and should not be confused with the American conservative writer of the same first and last name. The exploration of the combination of the four words used to describe George Grant – conservative, Canadian, nationalist, philosopher– is the backbone of this essay.

George Grant was not a narrowly partisan politician confined to the day-to-day mud-slinging and hurly-burly of “practical politics” — rather, he was a political philosopher who looked at society from a “world-historical” perspective. Although Grant wanted to be widely understood, his writing is far more abstract and abstruse, and far less crudely biased, than that found in “practical political” discourse.

George Grant was not an analytic philosopher (i.e., he loved broad vistas rather than minutiae); nor was he a political scientist in the sense of the kind of person in political studies who aspires to put on a lab coat to lend themselves prestige; nor was he a student of international relations; and certainly not an administrative or management theorist. By his preference for political philosophy, Grant set himself against the rising tide of disciplines, which are proceeding – despite some exotic postmodern fraying at the edges — in the direction of analytics, the scientific model, a mathematical modelling of international relations, and administrative and managerial approaches. Grant did not care about the “micro” of politics and society (such as that expressed in interminable statistical analysis), but about the “macro”, the really big picture. Specific historical instances were used by Grant to illustrate his “macro” thesis, rather than analyzed in themselves. He did not care about quantitative analysis of picayune events, but rather looks at why, rather than how, certain things happen.

George Grant, like other political philosophers, derived his views of society from a carefully defined set of first principles, most notably from a conception of human nature which differs from that of most modern thinkers.

To Grant, there are deep and fundamental distinctions between premodern and modern societies, which transcend the particular features of individual societies. The premodern and modern viewpoints or “world-views” make different assumptions about human nature, the purposes of human existence, and the place of humankind in the world, and therefore determine the type of society in which we live. In particular, Grant pays attention to what technology, and the interaction of humanity and technology, means. Because of the negative conclusions which he reaches about the “ideology of technology”, which he identifies with the modern world-view, Grant is generally critical of modern society.

The term “conservatism”, as used by George Grant, has almost nothing in common with its various current, conventional meanings and definitions. He uses the term in a special sense, which emerges from his “holistic” view of human history and social development. Today, most people associate “conservatism” as a political term with “neoconservatism”, the advocacy and espousal of the so-called free market (i.e., of capitalism), with tax-cuts, budget-reductions, big corporate profits, etc., as well as with a certain harshness, rigidity, and anti-idealism. In Canada, neoconservatism is often seen as an American import.

To George Grant, conservatism, properly defined, is the exact opposite — he is, in fact, vociferously anti-capitalist, because capitalism is seen by him as identical with that dominance of technology to which he is opposed. His own definition of “conservatism” is a highly eclectic one, which portrays it as a highly positive, life-affirming viewpoint, rooted in traditional philosophy and religion, especially Platonism and Christianity.

The meaning of the word “Tory”, which George Grant could in some sense be described, has undergone an remarkable evolution throughout history. Like the word “conservatism”, this word has a number of different meanings, virtually all of which have nothing to do with the way the word was being employed to describe the “Tory” government and party of Brian Mulroney in Canada in 1984-1993 — roughly meaning “political fat-cats and friends of big business”.

A better term to describe Grant would be “Red Tory” or “radical Tory”. However, one must be careful to include the reflective component in it, as many unreflective, Progressive Conservative party hacks in Canada, who simply wanted to adopt a left-liberal program to gain votes, have also been called “Red Tories”. Another term which could be applied to Grant is “high Tory”, the word “high” connoting both the sense of the philosophical and the religious.

The third point to be made is that George Grant called himself a Canadian nationalist. This is clearly at odds with the conventional contemporary definition of conservatism in Canada as pro-American, pro-capitalist, and pro-Free Trade. George Grant’s conception of himself as both a conservative and a Canadian nationalist is rooted in a certain view of modern history.

Just as there are many definitions of “conservatism” and “Toryism”, so too there are many definitions of nationalism. Nationalism is often a principle which virtually all persons in the national community, regardless of other political beliefs, can subscribe to. For example, in the Polish Second Republic, virtually all Poles believed in the necessity of a strong Poland, an effective military, and the strengthening of Poland’s place and position in the international order, regardless of party affiliation. Many of the minorities of the Second Republic, however, were against the Polish national consensus – although they were also citizens of the Polish state.

There can be various types of nationalism, which usually fall somewhere along a continuum based on “ethnicity”, to an identity based purely on “state”. All of the Anglo-American societies (including Britain and the United States) have heavily tended in the direction of “state” nationalism – which should have theoretically made them more tolerant and less exclusivist – although this in practice has not always been the case. And, as is discussed below, the prevalent form of Canadian nationalism today actually attacks the traditions of the British-inspired state, and of “the two nations” (English and French), in Canada. Grant’s version of Canadian nationalism, however, is as a truly conservative, traditionalist tendency. According to Grant – in contrast to some political theories that usually see nationalism as something modern — some types of nationalism can indeed be the expression of a premodern ethos or its residues in modern times.

One way of understanding George Grant’s view of the political spectrum is to use Marx’s categories for the different types of societies — feudal, capitalist, and socialist. The conservatism of George Grant is rooted in ideas reminiscent of feudalism, which are of course at odds with capitalism. Aristocracy, priesthood, kingship, honour, virtue, and so forth, are clearly in opposition to the values of the bourgeoisie, namely rationalism and functionalism and the supremacy of the cash-nexus. Individualist liberalism and capitalism are virtually identical, and are opposed to both feudalism and socialism.

According to the so-called Hartz-Horowitz thesis, socialism (this word is generally used by Gad Horowitz with the meaning of “social democracy”, not of a Soviet-style regime) is a modern “replacement” for feudalism, Toryism, conservatism, or what could be called premodern communitarian values. Canada was established as a “Tory-touched remnant” society, i.e., it was founded by the Loyalists (or Tories — supporters of the Monarchy), who were driven out of America as a result of the American Revolution. The English-Canadian Tories effectively made common cause with the Catholic French of Quebec. The Hartz-Horowitz thesis is that Canada, which was founded as a more feudal society than America, has the chance of a transition to socialism, as, under the impact of industrial progress, Toryism is “translated” into socialism. America, on the other hand, was founded as a pure individualist liberal society [1], and is therefore likely to remain purely liberal. Looking at the historical evidence, there have been no successful socialist third parties (or successful third parties of any kind) in America [2], unlike in Canada.

George Grant would doubtless consider it ironic that today, America is considered a bastion of conservatism, while Canada is seen as a more liberal and socialist oriented society. For a long period of Canadian history, it was the United States that appeared as the more liberal society, while it was Canada that was seen as the more conservative one. The War of 1812, for example, was perceived as the defence of a conservative and British-centred society against a more liberal American republicanism.

Gad Horowitz, taking note of the fact that both real Tories and socialists share an opposition to liberalism-capitalism, suggests an alliance between the remnants of true Toryism in Canada, and the socialists, against the liberal, pro-American, pro-capitalist, “middle” grouping. However, Horowitz believes that ultimately, only socialism will have the strength to keep capitalism at bay.

The world of Canadian politics has undergone unusually dramatic shifts. In the 1980s, the Tories or Progressive Conservatives (P.C.’s), traditionally the party of Canadian nationalism, protectionism, etc., had become a liberal-capitalist party. The Liberals, whose conventional policy had always been pro-U.S. continentalism (or, so-called “amalgamation”) had, in the 1980s, become Canadian nationalists. The Liberals, under the leadership of John Turner, fought against the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement in 1988. Turner was arguably more substantively conservative than Brian Mulroney on many issues. The New Democrats (New Democratic Party – NDP – Canada’s social democratic party) often described themselves as the most consistent Canadian nationalists in that decade. In the 1990s, however, it seemed that all of the parties in the federal Parliament had become liberal-capitalist, with greater or lesser degrees of fervour. There have remained though, large cultural industries and structures — together commanding greater resources than some major political parties — which make the persistence of Canadian identity possible. These might suggest to some that Canadian nationalism is alive and well, and that Canada — to put it in Grantian terms — has some chance of resisting the Americans.

However, it should be noted that the Canada of today is entirely different from that of the Canada of the early 1960s, when the struggle over the future of Canada between Diefenbaker and Pearson took place. According to Grant, the defeat of Diefenbaker in the 1963 election represented Canada’s final integration into the American technological empire. Prime Minister Diefenbaker had refused to accept U.S. nuclear weapons on Canadian soil, with the result that virtually all of the media instrumentalities and pollster expertise of the North American managerial classes were turned against him, in the ensuing election of 1963. Despite his thoroughgoing pessimism, Grant expressed some hope for an alliance of the old conservative nationalist communitarianism (such as that represented by Sir John A. Macdonald and his National Policy), with the new nationalist collectivism of the Left, to fight for what remained of Canada — against the dynamic, technological, liberal, individualist, and capitalist America.

Today, Canadian nationalism has been pushed into the position of a strong extra-parliamentary opposition. However, the messages being offered by such archetypically Canadian institutions as the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) should be examined carefully in relation to Canadian nationalism.

If one accepts George Grant’s Loyalist thesis, this means that Canada was, in essence, a British-inspired society at the moment of its founding — British North America. (The Act of Confederation, which received final approval from the British Parliament, was called in full the British North America Act.) It would seem logical that the spirit of Britishness was the only force which could have resisted Americanization. Yet, post-Pearson, Canada is based on an explicit rejection of the British origins of Canada

The ideas of Gad Horowitz, an old-fashioned socialist, do indeed overlap with those of George Grant. Gad Horowitz himself has made a harsh critique of current multiculturalism policies, and calls for the reassertion of English-Canadian nationalism, which he sees in political and not ethnic terms. Canada, if it is to be a country with a definable identity, can only be so as a British-inspired society, at least on the level of institutions and political culture. The denial of Britishness amounts to an embracing of Americanism, or so Gad Horowitz argues. And it is only in a British-inspired Canada that socialism canexist, because the essence of Americanism is individualist liberalism and capitalism. So, therefore, social democrats in English Canada must be English-Canadian nationalists.

In relation to Quèbec, Horowitz astutely advocated the formal recognition of its “special status” as early as the 1970s. This recognition — which might well have taken the wind out of the Quèbec separatists’ sails — was rejected by “the rest of Canada” in 1990 and 1992. Both the Meech Lake Accord and the Charlottetown Agreements failed.

Horowitz’s argument does seem to look somewhat archaic, in the current-day context of English-speaking Canada. Like George Grant’s definition of conservatism, Horowitz’s definition of socialism is quite unusual. Today, the New Democratic Party is in the vanguard of multiculturalism — and no other major party has criticized it (apart from some elements of the more conventionally right-wing Reform Party and its successor, the Canadian Alliance). Horowitz’s definition of socialism is more akin to that of the old, pre-war British Labour Party, or that of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (C.C.F.) in Canada, from which the New Democratic Party had emerged.

Eugene Forsey, a member of the old C.C.F., and a leading constitutional scholar, was someone who was conservative in regard to parliamentary institutions and Canada’s political culture generally, while being social democratic in regard to economics. He was one of only a few figures prominent on the national scene who expressed reservations about the new 1982 Constitution because it weakened Parliament, and made Canada more like America, with a formal “bill of rights” (the Charter of Rights and Freedoms), subject to judicial review (or judicial fiat), as opposed to the British and Canadian tradition of the sovereignty of Parliament.

Socialism, as Horowitz defines it, simply does not exist anymore. The New Democratic Party enthusiastically supports multiculturalism. Ostensibly liberationist social issues are also massively promoted. At the same time, consumerism, commercialism, big corporations, etc., are becoming more and more powerful, and Canada seems to be slipping into “the new economy” in which corporations make ever-more massive profits, while ever-more working people are laid off, with the usual neoconservative budget cutbacks.

George Parkin Grant criticized both capitalism and socialism from a traditionalist perspective. According to Grant’s radical critique of modernity, there is no ultimate contradiction between social liberalism or libertinism, as typified by the philosophy of Herbert Marcuse, and the catchphrase — “if it feels good, do it”; and economic conservatism (or neoconservatism) i.e. the dominance of the big corporations. Grant writes: “The directors of General Motors and the followers of Professor Marcuse sail down the same river in different boats.” Both impulses actually reinforce each other, and both serve to shut out any communitarian ideas from playing a part on the modern scene. Grant concludes that a socialism which does not question technology, technological development, and hedonism, is no different from capitalism.

Grant himself would be skeptical whether socialism, in the long run, can be any sort of alternative to capitalism. He did not reject an alliance of true Tories and socialists (on those issues where it may be possible); nor did he cease to hope that socialism would somehow be able to stop capitalism. But Grant believed that the abyss is opening up before humanity and nothing can be done to avoid it. Socialism, since it is, at root, materialistic, and non-religious, poses no real challenge to the status-quo. It too ultimately has a modern and technological outlook. It is but a different means to the same end, or rather, a different means to no end. [Editorial note. Certain socialists, notably Kurt Eisner, embraced both Marx and Kant, materialism but also idealism.]

For Grant, technology is a total, all-encompassing world-view and force, which has its own drives and tendencies, which end up being contrary to human nature. The whole technological system is hurtling “forward” on its own trajectories, with human beings its captive passengers. This “drive towards mastery of human and non-human nature”, this “spirit of dynamic technique”, is unstoppable and not amenable to change. Grant was in the ironic and paradoxical position of effectively being a technological determinist who criticizes technology, because it will result in the end of everything that has ever had meaning to humanity.

Canada, the neighbour of the most dynamic technological society that has ever existed in human history, is supposedly doomed to absorption into America. And if America is in moral and spiritual decline, then Canada must also be seen as disintegrating.

Grant’s main thesis is that the end result of technological liberalism will be a conceptually homogenous, universal, hyper-technological, hypermodern world-state in which all sense of humanity and human ethicality will be lost. It is difficult to argue with Grant’s thesis, if one accepts his description of technology and its inherent drives as valid. The only hope Grant leaves us with is the hope of Divine Providence — he ends one of his most important works (Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism, 1965) with a quote from Virgil’s Aeneid, “…their arms were outstretched to the further shore…”

ENDNOTES

[1] The partial exception to American individualist liberalism was the South – an exception that eventually was expunged by a savage, fratricidal war. However, it could be argued that traditional Canada was a more genuinely conservative society that (to a large extent) avoided entanglements with slavery and racism.

[2] That is, after the emergence of the Republican and Democratic “duopoly” whose ultimate origins can be traced to the mid-nineteenth century. Although the ideological configurations of the two parties have obviously been subject to highly drastic shifts since that time, the U.S. has continuously remained a two-party system.

Sociologist Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and researcher

Like this:

Like Loading...

In Memoriam, George Parkin Grant, 1918-1988

In Memoriam, George Parkin Grant,

1918-1988

By Mark Wegierski

George Parkin Grant (who usually called himself George Grant) is virtually unknown outside of Canada, and should not be confused with the American conservative writer of the same first and last name. The exploration of the combination of the four words used to describe George Grant – conservative, Canadian, nationalist, philosopher– is the backbone of this essay.

George Grant was not a narrowly partisan politician confined to the day-to-day mud-slinging and hurly-burly of “practical politics” — rather, he was a political philosopher who looked at society from a “world-historical” perspective. Although Grant wanted to be widely understood, his writing is far more abstract and abstruse, and far less crudely biased, than that found in “practical political” discourse.

George Grant was not an analytic philosopher (i.e., he loved broad vistas rather than minutiae); nor was he a political scientist in the sense of the kind of person in political studies who aspires to put on a lab coat to lend themselves prestige; nor was he a student of international relations; and certainly not an administrative or management theorist. By his preference for political philosophy, Grant set himself against the rising tide of disciplines, which are proceeding – despite some exotic postmodern fraying at the edges — in the direction of analytics, the scientific model, a mathematical modelling of international relations, and administrative and managerial approaches. Grant did not care about the “micro” of politics and society (such as that expressed in interminable statistical analysis), but about the “macro”, the really big picture. Specific historical instances were used by Grant to illustrate his “macro” thesis, rather than analyzed in themselves. He did not care about quantitative analysis of picayune events, but rather looks at why, rather than how, certain things happen.

George Grant, like other political philosophers, derived his views of society from a carefully defined set of first principles, most notably from a conception of human nature which differs from that of most modern thinkers.

To Grant, there are deep and fundamental distinctions between premodern and modern societies, which transcend the particular features of individual societies. The premodern and modern viewpoints or “world-views” make different assumptions about human nature, the purposes of human existence, and the place of humankind in the world, and therefore determine the type of society in which we live. In particular, Grant pays attention to what technology, and the interaction of humanity and technology, means. Because of the negative conclusions which he reaches about the “ideology of technology”, which he identifies with the modern world-view, Grant is generally critical of modern society.

The term “conservatism”, as used by George Grant, has almost nothing in common with its various current, conventional meanings and definitions. He uses the term in a special sense, which emerges from his “holistic” view of human history and social development. Today, most people associate “conservatism” as a political term with “neoconservatism”, the advocacy and espousal of the so-called free market (i.e., of capitalism), with tax-cuts, budget-reductions, big corporate profits, etc., as well as with a certain harshness, rigidity, and anti-idealism. In Canada, neoconservatism is often seen as an American import.

To George Grant, conservatism, properly defined, is the exact opposite — he is, in fact, vociferously anti-capitalist, because capitalism is seen by him as identical with that dominance of technology to which he is opposed. His own definition of “conservatism” is a highly eclectic one, which portrays it as a highly positive, life-affirming viewpoint, rooted in traditional philosophy and religion, especially Platonism and Christianity.

The meaning of the word “Tory”, which George Grant could in some sense be described, has undergone an remarkable evolution throughout history. Like the word “conservatism”, this word has a number of different meanings, virtually all of which have nothing to do with the way the word was being employed to describe the “Tory” government and party of Brian Mulroney in Canada in 1984-1993 — roughly meaning “political fat-cats and friends of big business”.

A better term to describe Grant would be “Red Tory” or “radical Tory”. However, one must be careful to include the reflective component in it, as many unreflective, Progressive Conservative party hacks in Canada, who simply wanted to adopt a left-liberal program to gain votes, have also been called “Red Tories”. Another term which could be applied to Grant is “high Tory”, the word “high” connoting both the sense of the philosophical and the religious.

The third point to be made is that George Grant called himself a Canadian nationalist. This is clearly at odds with the conventional contemporary definition of conservatism in Canada as pro-American, pro-capitalist, and pro-Free Trade. George Grant’s conception of himself as both a conservative and a Canadian nationalist is rooted in a certain view of modern history.

Just as there are many definitions of “conservatism” and “Toryism”, so too there are many definitions of nationalism. Nationalism is often a principle which virtually all persons in the national community, regardless of other political beliefs, can subscribe to. For example, in the Polish Second Republic, virtually all Poles believed in the necessity of a strong Poland, an effective military, and the strengthening of Poland’s place and position in the international order, regardless of party affiliation. Many of the minorities of the Second Republic, however, were against the Polish national consensus – although they were also citizens of the Polish state.

There can be various types of nationalism, which usually fall somewhere along a continuum based on “ethnicity”, to an identity based purely on “state”. All of the Anglo-American societies (including Britain and the United States) have heavily tended in the direction of “state” nationalism – which should have theoretically made them more tolerant and less exclusivist – although this in practice has not always been the case. And, as is discussed below, the prevalent form of Canadian nationalism today actually attacks the traditions of the British-inspired state, and of “the two nations” (English and French), in Canada. Grant’s version of Canadian nationalism, however, is as a truly conservative, traditionalist tendency. According to Grant – in contrast to some political theories that usually see nationalism as something modern — some types of nationalism can indeed be the expression of a premodern ethos or its residues in modern times.

One way of understanding George Grant’s view of the political spectrum is to use Marx’s categories for the different types of societies — feudal, capitalist, and socialist. The conservatism of George Grant is rooted in ideas reminiscent of feudalism, which are of course at odds with capitalism. Aristocracy, priesthood, kingship, honour, virtue, and so forth, are clearly in opposition to the values of the bourgeoisie, namely rationalism and functionalism and the supremacy of the cash-nexus. Individualist liberalism and capitalism are virtually identical, and are opposed to both feudalism and socialism.

According to the so-called Hartz-Horowitz thesis, socialism (this word is generally used by Gad Horowitz with the meaning of “social democracy”, not of a Soviet-style regime) is a modern “replacement” for feudalism, Toryism, conservatism, or what could be called premodern communitarian values. Canada was established as a “Tory-touched remnant” society, i.e., it was founded by the Loyalists (or Tories — supporters of the Monarchy), who were driven out of America as a result of the American Revolution. The English-Canadian Tories effectively made common cause with the Catholic French of Quebec. The Hartz-Horowitz thesis is that Canada, which was founded as a more feudal society than America, has the chance of a transition to socialism, as, under the impact of industrial progress, Toryism is “translated” into socialism. America, on the other hand, was founded as a pure individualist liberal society [1], and is therefore likely to remain purely liberal. Looking at the historical evidence, there have been no successful socialist third parties (or successful third parties of any kind) in America [2], unlike in Canada.

George Grant would doubtless consider it ironic that today, America is considered a bastion of conservatism, while Canada is seen as a more liberal and socialist oriented society. For a long period of Canadian history, it was the United States that appeared as the more liberal society, while it was Canada that was seen as the more conservative one. The War of 1812, for example, was perceived as the defence of a conservative and British-centred society against a more liberal American republicanism.

Gad Horowitz, taking note of the fact that both real Tories and socialists share an opposition to liberalism-capitalism, suggests an alliance between the remnants of true Toryism in Canada, and the socialists, against the liberal, pro-American, pro-capitalist, “middle” grouping. However, Horowitz believes that ultimately, only socialism will have the strength to keep capitalism at bay.

The world of Canadian politics has undergone unusually dramatic shifts. In the 1980s, the Tories or Progressive Conservatives (P.C.’s), traditionally the party of Canadian nationalism, protectionism, etc., had become a liberal-capitalist party. The Liberals, whose conventional policy had always been pro-U.S. continentalism (or, so-called “amalgamation”) had, in the 1980s, become Canadian nationalists. The Liberals, under the leadership of John Turner, fought against the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement in 1988. Turner was arguably more substantively conservative than Brian Mulroney on many issues. The New Democrats (New Democratic Party – NDP – Canada’s social democratic party) often described themselves as the most consistent Canadian nationalists in that decade. In the 1990s, however, it seemed that all of the parties in the federal Parliament had become liberal-capitalist, with greater or lesser degrees of fervour. There have remained though, large cultural industries and structures — together commanding greater resources than some major political parties — which make the persistence of Canadian identity possible. These might suggest to some that Canadian nationalism is alive and well, and that Canada — to put it in Grantian terms — has some chance of resisting the Americans.

However, it should be noted that the Canada of today is entirely different from that of the Canada of the early 1960s, when the struggle over the future of Canada between Diefenbaker and Pearson took place. According to Grant, the defeat of Diefenbaker in the 1963 election represented Canada’s final integration into the American technological empire. Prime Minister Diefenbaker had refused to accept U.S. nuclear weapons on Canadian soil, with the result that virtually all of the media instrumentalities and pollster expertise of the North American managerial classes were turned against him, in the ensuing election of 1963. Despite his thoroughgoing pessimism, Grant expressed some hope for an alliance of the old conservative nationalist communitarianism (such as that represented by Sir John A. Macdonald and his National Policy), with the new nationalist collectivism of the Left, to fight for what remained of Canada — against the dynamic, technological, liberal, individualist, and capitalist America.

Today, Canadian nationalism has been pushed into the position of a strong extra-parliamentary opposition. However, the messages being offered by such archetypically Canadian institutions as the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) should be examined carefully in relation to Canadian nationalism.

If one accepts George Grant’s Loyalist thesis, this means that Canada was, in essence, a British-inspired society at the moment of its founding — British North America. (The Act of Confederation, which received final approval from the British Parliament, was called in full the British North America Act.) It would seem logical that the spirit of Britishness was the only force which could have resisted Americanization. Yet, post-Pearson, Canada is based on an explicit rejection of the British origins of Canada

The ideas of Gad Horowitz, an old-fashioned socialist, do indeed overlap with those of George Grant. Gad Horowitz himself has made a harsh critique of current multiculturalism policies, and calls for the reassertion of English-Canadian nationalism, which he sees in political and not ethnic terms. Canada, if it is to be a country with a definable identity, can only be so as a British-inspired society, at least on the level of institutions and political culture. The denial of Britishness amounts to an embracing of Americanism, or so Gad Horowitz argues. And it is only in a British-inspired Canada that socialism canexist, because the essence of Americanism is individualist liberalism and capitalism. So, therefore, social democrats in English Canada must be English-Canadian nationalists.

In relation to Quèbec, Horowitz astutely advocated the formal recognition of its “special status” as early as the 1970s. This recognition — which might well have taken the wind out of the Quèbec separatists’ sails — was rejected by “the rest of Canada” in 1990 and 1992. Both the Meech Lake Accord and the Charlottetown Agreements failed.

Horowitz’s argument does seem to look somewhat archaic, in the current-day context of English-speaking Canada. Like George Grant’s definition of conservatism, Horowitz’s definition of socialism is quite unusual. Today, the New Democratic Party is in the vanguard of multiculturalism — and no other major party has criticized it (apart from some elements of the more conventionally right-wing Reform Party and its successor, the Canadian Alliance). Horowitz’s definition of socialism is more akin to that of the old, pre-war British Labour Party, or that of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (C.C.F.) in Canada, from which the New Democratic Party had emerged.

Eugene Forsey, a member of the old C.C.F., and a leading constitutional scholar, was someone who was conservative in regard to parliamentary institutions and Canada’s political culture generally, while being social democratic in regard to economics. He was one of only a few figures prominent on the national scene who expressed reservations about the new 1982 Constitution because it weakened Parliament, and made Canada more like America, with a formal “bill of rights” (the Charter of Rights and Freedoms), subject to judicial review (or judicial fiat), as opposed to the British and Canadian tradition of the sovereignty of Parliament.

Socialism, as Horowitz defines it, simply does not exist anymore. The New Democratic Party enthusiastically supports multiculturalism. Ostensibly liberationist social issues are also massively promoted. At the same time, consumerism, commercialism, big corporations, etc., are becoming more and more powerful, and Canada seems to be slipping into “the new economy” in which corporations make ever-more massive profits, while ever-more working people are laid off, with the usual neoconservative budget cutbacks.

George Parkin Grant criticized both capitalism and socialism from a traditionalist perspective. According to Grant’s radical critique of modernity, there is no ultimate contradiction between social liberalism or libertinism, as typified by the philosophy of Herbert Marcuse, and the catchphrase — “if it feels good, do it”; and economic conservatism (or neoconservatism) i.e. the dominance of the big corporations. Grant writes: “The directors of General Motors and the followers of Professor Marcuse sail down the same river in different boats.” Both impulses actually reinforce each other, and both serve to shut out any communitarian ideas from playing a part on the modern scene. Grant concludes that a socialism which does not question technology, technological development, and hedonism, is no different from capitalism.

Grant himself would be skeptical whether socialism, in the long run, can be any sort of alternative to capitalism. He did not reject an alliance of true Tories and socialists (on those issues where it may be possible); nor did he cease to hope that socialism would somehow be able to stop capitalism. But Grant believed that the abyss is opening up before humanity and nothing can be done to avoid it. Socialism, since it is, at root, materialistic, and non-religious, poses no real challenge to the status-quo. It too ultimately has a modern and technological outlook. It is but a different means to the same end, or rather, a different means to no end. [Editorial note. Certain socialists, notably Kurt Eisner, embraced both Marx and Kant, materialism but also idealism.]

For Grant, technology is a total, all-encompassing world-view and force, which has its own drives and tendencies, which end up being contrary to human nature. The whole technological system is hurtling “forward” on its own trajectories, with human beings its captive passengers. This “drive towards mastery of human and non-human nature”, this “spirit of dynamic technique”, is unstoppable and not amenable to change. Grant was in the ironic and paradoxical position of effectively being a technological determinist who criticizes technology, because it will result in the end of everything that has ever had meaning to humanity.

Canada, the neighbour of the most dynamic technological society that has ever existed in human history, is supposedly doomed to absorption into America. And if America is in moral and spiritual decline, then Canada must also be seen as disintegrating.

Grant’s main thesis is that the end result of technological liberalism will be a conceptually homogenous, universal, hyper-technological, hypermodern world-state in which all sense of humanity and human ethicality will be lost. It is difficult to argue with Grant’s thesis, if one accepts his description of technology and its inherent drives as valid. The only hope Grant leaves us with is the hope of Divine Providence — he ends one of his most important works (Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism, 1965) with a quote from Virgil’s Aeneid, “…their arms were outstretched to the further shore…”

ENDNOTES

[1] The partial exception to American individualist liberalism was the South – an exception that eventually was expunged by a savage, fratricidal war. However, it could be argued that traditional Canada was a more genuinely conservative society that (to a large extent) avoided entanglements with slavery and racism.

[2] That is, after the emergence of the Republican and Democratic “duopoly” whose ultimate origins can be traced to the mid-nineteenth century. Although the ideological configurations of the two parties have obviously been subject to highly drastic shifts since that time, the U.S. has continuously remained a two-party system.

Sociologist Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and researcher

Share this:

Like this: