WW1 German AA Gun and Crew

First Total War

Frank Ellis confronts the dark side of modernity

Alexander Watson, Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914-1918, Allen Lane, London, 2014, with maps, photos, notes, bibliography and index. ISBN 978-1-846-14221-5

Vielleicht opfern wir auch uns für etwas Unwesentliches. Aber unseren Wert kann uns keiner nehmen. Nicht wofür wir kämpfen ist das Wesentliche, sondern wie wir kämpfen. Dem Ziel entgegen, bis wir siegen oder bleiben. Das Kämpfertum, der Einsatz der Person, und sei es für die allerkleinste Idee, wiegt schwerer als alles Grübeln über Gut und Böse.[Ernst Jünger, Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis]

Based on some valuable source material and clearly written, Ring of Steel is a worthy project with which to mark the one hundredth anniversary of the start of the Great War, though the author’s claim, even allowing for the circumscribing effect of ‘modern’, viz that – ‘This book is the first modern history to narrate the Great War from the perspectives of the two major Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary’[1] – is exaggerated. No matter, Ring of Steel is a good and serious read, with the emphasis falling on how Germany and its Austro-Hungarian ally coped with the blockade – the ring of steel – that slowly strangled them during World War I and the tactical and strategic decisions taken by the Central Powers in order to seize the initiative from their two main opponents, Britain and France, in order to avoid defeat.

Although the American Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War provided some idea of the huge technological changes that had taken place in the prosecution of war in the latter half of the nineteenth century, offering pointers to how a European-wide conflagration might develop, by 1914, the start of the Great European Civil War, the destructive power of modern armies and navies, and eventually the first air forces, had exceeded the ability and imagination of military and civilian planners fully to comprehend the nature of the violence that they were now able to unleash. In fact, 1914 marked the start of a new type of war – total war – and by 1918 it was total: mass conscription; rationing (actual starvation in parts of the Central Powers); genocide (Armenia); rampant inflation; indifference to mass slaughter; government censorship; seizure of private assets; unrestricted submarine warfare (a disastrous German move); British naval blockade (of dubious legality as Watson argues); multiracial strife; ethnic cleansing and deportations; air raids; and towards the end a hideous influenza pandemic that cut down millions.

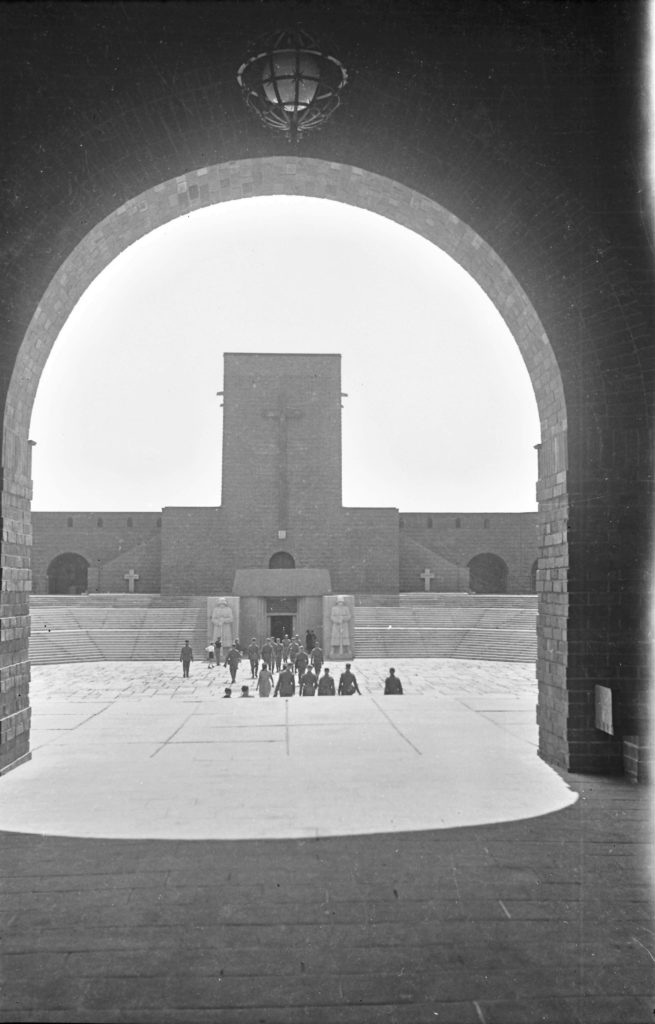

Tannenberg Memorial

These outcomes were bad enough but as a result of the chaos of war and the ineptitude of the Tsarist government Lenin and his gangsters were able to seize power in Russia. From the misery of total war emerged a new type of state, the totalitarian state, the Soviet Union, based on the ideology of class war, red terror and striving for global domination. Moreover, after the war there were huge population displacements, especially of Germans; some 13 million were now outside the Reich’s borders. This would have been a gift to any nationalist politician, never mind someone as politically brilliant and ruthless as Hitler. Combined with the injustices of Versailles – Article 231 of the Versailles Treaty was deemed by the German delegation to be the “war-guilt clause” – starvation, war reparations and hyperinflation, this massive population displacement and the very real Bolshevik threat prompted a violent nationalist reaction in Germany out of which Hitler’s National-Socialist German Workers’ Party eventually emerged as the dominant faction and the serious contender for power.

One obvious conclusion derived from Ring of Steel is that the combat performance of the Austro-Hungarian component was massively weakened by racial and cultural diversity. By language, Germans, Magyars, Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenes, Poles, Slovenes, Serbo-Croats, Romanians and Italians were all represented. The longer the war lasted the more this fragile unity was tested, the more ethnic loyalties asserted themselves, whereas inside Germany all the signs were that Germans whatever their political allegiances rallied, focusing to begin with on Tsarist Russia and then on Britain as the main enemy (encapsulated in the slogan: ‘Gott strafe England’).

The nation-wide commitment to maintain Burgfrieden according to which all political in-fighting was suspended while the war lasted had no real chance in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. To cite Watson: ‘The lack of an Austria-wide Burgfrieden also meant that bonds of solidarity strengthened within, rather than between, ethnicities’.[2] This confuses cause and consequence: it was the fissiparous nature of multiethnicity that ruled out any possibility of a Burgfrieden from the very beginning: diversity in adversity is emphatically not a strength. In fact, Watson more or less acknowledges the dangers of diversity in adversity: ‘The ethnic tensions and suspicions inflamed by the assassination [Emperor Franz Ferdinand] across the Habsburg Empire should have cast doubt on the unreasoned faith that armed conflict would somehow bring greater unity to a divided realm’.[3] In Germany, on the other hand, Prussian refugees, fleeing Russian terror, were welcomed, whereas Galician refugees met a hostile reception from Austrians. According to Watson this was due to the fact that ‘To a large degree, this reflected the more tenuous ties between (sic) peoples in a multi-ethnic empire compared with the solid “imagined community” of a modern nation state’.[4] To put this more forcefully, racial and cultural homogeneity strengthen bonds – surely obvious – racial and cultural heterogeneity weaken them, disastrously so in fact. It also strikes this reviewer as insulting to regard the state of Germany in 1914 or the tight-knit communities of Galician Jews as ‘imagined communities’. Jewish communities and the ancient nation states of England, France, Russia, China and Japan were not figments of the political imagination. These ancient nations embodied many centuries of shared blood, glory and shame. Nor could they just be “unimagined” – “deconstructed” in the jargon – and made not to exist. Despite his perhaps unwitting appeal to neo-Marxist “imagined communities”, the evidence, much of it cited by Watson himself, shows that multiethnic (multiracial) empires are highly unstable in moments of crisis. Syria and the murder and slaughter in Iraq are just the most recent examples.

Watson’s attempts to play down the patriotic fervour at the start of the war are not entirely convincing. The memoirs of Ernst Jünger – there are no references to Jünger or his work at all in Ring of Steel, an astonishing omission – leave little doubt about the patriotic fervour that gripped Germany and, for combatants such as Jünger, the sense of adventure offered by the start of war. The fact that there were very large anti-war meetings in Germany between 28th-30th July 1914 is all well and good but many of these socialist protestors went to war in the end. Watson, having tried to play down the upsurge of war and patriotic fervour, records the remarks of the Berlin police chief who noted that people, members of the SPD (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands), who only recently were cheering the Internationale in protest meetings now bubble over with patriotism.[5] Germans who supported the Social-Democrats went to war for Germany because blood is thicker than water; because Germany despite all the Marxist propaganda about international worker solidarity meant more to them than love of the English and French proletariat. That is as it should be.

Watson does, however, show a good grasp of the qualities that made the German Army so formidable. First, the intellectual standards required for its senior officers and planners were much higher than those in other armies, the British appearing amateurish by comparison. One of the main doctrines of the German army, one that was carried over into World War II, was Auftragstaktik. Watson translates this as ‘mission tactics’, whereas I would prefer ‘mission-led command’. The critical thing about Auftragstaktik is that subordinate commanders were given a mission and then required to solve it. German junior leaders, unlike in other armies, were not micro-managed. They were expected to make decisions, show initiative, solve problems and, if opportunities arose, to inflict damage on the enemy. For some bizarre reason Watson characterises the doctrine of Auftragstaktik as ‘infamous’[6] when in fact it was one of the great strengths of the German army and, by contrast, underlined the distinct lack of trust felt by British commanders in their subordinates. The German cadre of non-commissioned officers, unlike their British counterparts, constituted an élite professional body, often discharging duties which in other armies would be the preserve of officers. The German emphasis on initiative at all levels of command meant that Western propaganda which depicted German soldiers as unthinking robots was very wide of the mark. On the subject of the German navy there can be no doubt that Germans felt an immense pride in the German navy and the challenge it represented to Britain’s Royal Navy. Yet, bottled up in harbour after the battle of Jutland, sailors in the German fleet proved to be very susceptible to the ideas of the Russian revolution, becoming something of a liability.

One of the most important aspects to this book and one that poses a severe challenge to a lot of German historiography on World War I (and World War II) is that Watson documents the savagery of the Tsarist army on German territory at the start of the war. This is important for German planning prior to the start of Barbarossa in 1941 since Tsarist-Russian behaviour scarred German memory and fed German fears before the start of Barbarossa about the way German prisoners would be treated were they captured by the Red Army. Especially striking is how Tsarist-Russian behaviour anticipates the way the Red Army and the NKVD would behave after 1918, though, of course, the state terror perpetrated by the organs of the NKVD dwarfed anything carried out by Tsarist Russia.

What is not widely recognised even today is that Tsarist-Russian plans for Galicia were clearly racial and that the war was regarded as one for racial unity. There are, as Watson notes, though with some qualification, clear parallels with Nazi plans in 1941: ‘While Tsarist plans did not share the Nazis’ genocidal intent, they placed racial considerations at the centre of the region’s future, contravened international law, and caused tremendous suffering to hundreds of thousands of people in 1914-15’.[7] Allenstein, some 50 kilometres from Prussia’s south-eastern border, was one of the first Prussian towns to be occupied by the Russians (The occupation is also dealt with by Solzhenitsyn in August 1914 (1971 & 1989) and Watson would have found it useful to have examined Solzhenitsyn’s account). On entering Allenstein, the Russian invaders demanded huge amounts of food from the German inhabitants: 120,00 kilograms of bread; 6,000 kilograms of sugar; 5,000 kilograms of salt; 3,000 kilograms of tea; 15,000 kilograms of grits/rice; and 160 kilograms of pepper. Compared, however, with the immense damage inflicted by the Russians on other Prussian towns and villages, Allenstein was lucky. In other areas, the Russian commander, General Rennenkampf, let it be known to the civilian inhabitants that attacks on Russian troops would be punished mercilessly regardless of sex or age. He also threatened collective punishment, a clear violation of international law. Watson describes the Russian state of mind during this invasion: ‘There were also paranoid accusations of armed resistance. Francs tireurs were rumoured to rove the countryside on motorcycles and bicycles, German soldiers in mufti to be mingling among the population, and seemingly innocuous civilians to be plotting to poison unsuspecting Tsarist soldiers’.[8] Moreover, the fact that cycles were so rare in poverty-stricken Russia, Germans on bikes were assumed to be in the German Army or working for it.

As far as the Russians were concerned, security mandated mass deportations. To quote Watson: ‘The Russian Army’s most distinctive and extensively used tool of oppression was deportation. New Field Regulations issued at the end of July 1914 granted the Tsarist army unlimited authority over the population in war zones, including this power of removal. Whether in international law it was legal was more ambiguous, for its use had not been foreseen’.[9] In fact, these New Field Regulations anticipate any number of German decrees and orders in World War II and in a foretaste of what the NKVD would do in the Soviet period hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were deported from border zones. Dumped on the Volga or between the Volga and Urals, those that were deported endured untold misery and suffering. Yet, as Watson notes, ‘The thousands of East Prussians deported to the Volga were dwarfed by the hundreds of thousands of people from Russia’s own German minority cleared from western regions’.[10] Russian behaviour stiffened German resistance. In Watson’s words: ‘For the rest of the conflict, East Prussia would stand as an awful warning of the consequences of allowing enemy troops onto German soil. The memories and myths of the invasions would retain their ability to mobilize and unify the German people long after all danger from the Russians had passed’.[11] Contemporary German historians seem very reluctant to acknowledge that such memories may have played a role in determining German attitudes towards the Soviet state.

On 16th July 1941, Hitler, conferring with his senior planners on the progress of the Russian campaign, stated that ‘The vast area must, of course, be pacified as quickly as possible. The best way for this to happen is that any person who so much as looks askance is shot dead’. All the evidence cited by Watson shows that the Cossack units in the Tsarist army behaved in exactly the same way. These units were also violently anti-Semitic and when they engaged in Jew baiting, locals – Poles and Ruthenian peasants – took part. Again, the parallel with what would happen after the Germans invaded the Soviet Union is striking, especially in the Baltic States. In the Russian occupation zone in Galicia the Russian Governor General, Count Georgii Bobrinskii, even tried to russify the zone. There were more deportations and the Russian language was imposed. Ruthenes were encouraged by the Russians to loot Polish property and estates but the people who suffered the most from these dispossessions and baiting were – once again no surprise here – Galicia’s long-suffering Jews. As the Russians were forced out by the Germans, they, the Russians, pursued a scorched-earth policy. Worse still, as the Tsarist army retreated, it deported 3.3 million civilians. Watson notes the German reaction: ‘Advancing into the deliberately devastated landscape, encountering scattered, desperate and dispossessed inhabitants, German soldiers could be left in no doubt that they faced an evil empire’.[12] Indeed, and these memories persisted, festered and were exploited by nationalist politicians.

The biggest threat to the ability of the Central Powers to prosecute a long war was the British naval blockade. The reduction in foodstuffs had to be made good and this prompted a German administrative regime in the eastern territories, which was intended to maximise the sequestering and production of agricultural products and to ensure absolute food security. For example, Lithuania and Courland were envisaged as areas of German expansion – they were referred to as Ober Ost – and were ruled over, to begin with, by Erich Ludendorff, then the chief of staff on the Eastern Front. The whole concept of Ober Ost clearly anticipates later Nazi plans for the agricultural exploitation of the occupied Soviet territories, as laid out by Hermann Göring, though to be fair to Ludendorff there was no intention to starve people to death, as was clearly provided for in Nazi plans. A pertinent question here, it seems to me, is whether the British starvation blockade aimed primarily against Germany in World War I played any part in inspiring NS policies of mass exploitation of Soviet territories in WW II and a willingness to countenance mass starvation.

Lessons to be drawn from the Great European Civil War are, firstly, that it swept away all hopes that major wars were a thing of the past and, secondly, that any kind of internationalism, in the first instance, global socialism – and currently we-are-the-world multiculturalism – would prevent wars. Various manifestations of socialism actually caused wars. One hundred years on, there is more than enough uncertainty, latent instability, danger, and actual conflict in Europe and elsewhere to reject the perverse and dangerously naive view of the world peddled by EU politicians that all problems and conflicts are amenable to discussion. The lesson of history is quite clear: when states see their vital interests threatened, they resort to force or threaten the use of force. Russian moves against Ukraine, above all Crimea, and the Chinese-Japanese territorial dispute, are just the latest examples. Rest assured, there will be many more to come.

© Frank Ellis 2015

Dr Frank Ellis is an historian and author

[1] Ring of Steel, p.1

[2] ibid., p.96

[3] ibid., pp.60-61

[4] ibid., p.203

[5] ibid., p.84

[6] ibid., p.109

[7] ibid., p.162

[8] ibid., p.172

[9] ibid., p.177

[10] ibid., p.195

[11] ibid., p.181

[12] ibid., p.268

As usual Frank Ellis is cogent and readable but not wholly persuasive. The problem rests mainly with his assumption that the nation-state is a permanent entity in human history and that human history is the better for it. In fact, this article makes a fine, if unintended, argument that the nation-state of the epoch in question became an evil which must, however gradually, be dismantled. Mankind may urgently need the rule of law, but it suffered too much from the kind of swollen football-hooliganism that the European nations fell into – that surely is the lesson of their 20th century ‘civil war’.

Becoming specific about the logical glissandos Ellis’s thinking is prey to, what is to be made of the assertion with which he rounds off this passage: ‘Germans who supported the Social-Democrats went to war for Germany because blood is thicker than water; because Germany despite all the Marxist propaganda about international worker solidarity meant more to them than love of the English and French proletariat. That is as it should be.’ I cannot for the life of me think why ‘that is as it should be’, and I’m have no doubt that if Ellis were to encounter the reverse of the proposition from another author he would mock it. Blood may or may not be ‘thicker than water’ as the common cliché would have it, but to any Christian – and I suppose Ellis would see himself as in a Christian tradition – blood has a sacramental significance beyond all these man-made categories and confines and is supposed to engender love for all.