Sir Francis Galton, by Octavius Oakley, credit National Portrait Gallery

Eternal Recurrence

Superior: The Return of Race Science, Angela Saini, 4thEstate, 2019, 342pp, reviewed by Ed Dutton

Angela Saini can skilfully encapsulate her subject in a striking yet poignant image, so that the reader feels what this Guardian journalist wants them to feel: that ‘race’ is simply a means by which white people subjugate other ‘races’, that anyone who thinks that ‘race’ is a biological reality should feel guilty, and that ‘race’ has hurt people like Angela, an ethnic Punjabi, born in Newham and raised around Welling in southeast London.

In one of the most memorable examples of this writing skill in her new book Superior, she takes us on a journey. She has travelled widely to research this book, from interviewing an Aborigine in Australia whose parents were forcibly removed from their families, to conversing with a geneticist in India who suggests that caste correlates with cognitive ability – to a long-forgotten area of Paris. In 1907, it played host to the Paris Exposition, a giant outdoor anthropology museum in which people of different races were placed in simplified mock-ups of their own homeland so that Westerners could observe them, like exotic animals in a zoo. Angela brings the scene to life, stimulating our senses so that we ‘feel’ that we are in Paris with her and then she adds:

‘To one side is a weathered sculpture of a naked woman, reclining and covered in beads, her head gone, if it was ever there at all. A solitary jogger runs past’ (p.46).

In this short paragraph, Angela connects us to the human zoo, and what it represented; decay and death, pornography, the exploitation of females, and to Ancient Greece and its worship of the human form, but also to the scientific fervour of the Ancient world.

Angela Devi Saini has a degree in Engineering from Oxford. The daughter of a Hindu mother and, she implies, a Sikh father, her paternal grandfather fought in the British Army (p.72). Angela’s weapon, however, is her fluency. Superior isn’t so much a work of popular science as a latter day Bell Jar, with the focus turned from an American girl having a breakdown to a second generation Indian immigrant to London working through her feelings about ‘race.’

Beneath the beguiling prose, what Saini is saying is simple, and can be easily refuted. ‘The key to understanding the meaning of race is understanding power’ (p.3), she states. In other words, the author is a postmodernist who believes that there is no such thing as objective truth, because all narratives of supposed truth can be reduced to power. This is a manifestly inconsistent position, because if there is no such thing as objective truth then you can’t attempt to search for such a truth, yet Saini tells us that when she began the book she ‘wanted to understand the biological facts around race’ (p.3). Thus, there are objective facts and these exist independent of ‘power.’

Saini presents the usual assorted, fallacious arguments employed by emotional researchers against race. She notes that the concept of ‘race,’ in historical terms, is a relatively ‘new’ one. But this has no bearing whatsoever on whether dividing humanity up into breeding populations that differ genetically from other populations as a result of geographical isolation, cultural separation, and endogamy, and which show patterns of genotypic frequency for a number of inter-correlated characteristics compared with other breeding populations (the essence of ‘race’) allows correct predictions to be made. If so doing does allow correct predictions to be made, then ‘race’ is as much a ‘scientific’ category as any other.

Saini argues that there is no clear, agreed upon definition of race (p.200). But that could be claimed with regard to any concept. Nobody, she avers, has ever found a gene that is only present in one race (p.183). But this is unimportant, because ‘race’ is a matter of ‘gene frequencies’ not specific genes. Race, she maintains, isn’t ‘immutable,’ as if that matters (p.41). Races, by definition, are undergoing a process of constant evolution, ultimately towards separate species. Also, nothing is ‘immutable,’ not even the elements of the periodic table, so the fact that race isn’t is not relevant.

Racial divisions, we are informed, are merely ‘cultural’ and ‘driven by expediency’ (p.99). But all concepts are ‘cultural’ – the real question is: do they allow correct predictions to be made? Moreover, science, in searching for the most parsimonious explanation, will always be driven by ‘expediency.’ It is ‘expedient’ to divide reality into predictive categories. There will always be things on the borders of those categories, but do the categories have predictive power?

Saini contends that ‘there was far more variation between people of the same race than between supposedly separate races’ (p.56). This fallacious argument never goes way. Firstly, if we lump humans together with chimpanzees, there is more variation among that group than between humans and chimpanzees. But that doesn’t mean that dividing us up into humans and chimpanzees doesn’t allow correct and important predictions to be made. The same point could be made about dogs, but there are massive behavioural, intelligence, and physical differences between different breeds of dog. Would Angela Saini prefer to let her young son play with a Rottweiler or a Spaniel? Thirdly, the number of differences is less important than the direction of the differences. If a number of small differences all push in the same direction – which they will in the case of subspecies adapted to different ecologies – then this can add up to significant overall differences. An assiduous journalist researching a book on race should have encountered these counter-arguments as in Cochran and Harpending’s The 10,000 Year Explosion. Either she hasn’t read widely or she ignores arguments that refute her thesis.

Similar problems occur when Saini considers race differences in intelligence. She maintains that IQ tests are unfair to blacks; that there is debate over what the best IQ test is; that nobody has found genes there are associated with intelligence and that ‘scientists like Robert Plomin must be able to point to genes responsible for the effects they claim to see’ (p.155). It can be countered, of course, that blacks do worse on the more culture fair tests, that there’s debate over the utility of anything in science, that the differences correlate in the expected direction with objective intelligence measures such as reaction times, and that there are indeed alleles that are associated with very high IQ and the race differences in the prevalence of these correlate at 0.9 with race differences in IQ score (for an up-to-date summary of the research see my book The Silent Rape Epidemic).

Concerning the Flynn Effect (p.159), Saini concludes that we are becoming more intelligent and that therefore intelligence can’t possibly be genetic. One day in the future primitive tribesmen will be as intelligent as anyone else.

However, in Are We Getting Smarter?, James Flynn points out that his ‘effect’ has involved massive gains on the parts of the IQ test which a very weakly related to the core, and strongly genetic, ‘general intelligence.’ Our increasingly scientific society has pushed us to our phenotypic maximum on these ‘specialised abilities’. Due to the imperfect ability of the IQ test as a measurer of intelligence, our IQs have gone up. But there is no evidence that our general intelligence has increased. Indeed, as myself Michael Woodley of Menie have shown in At Our Wits’ End: Why We’re Becoming Less Intelligent and What It Means For the Future, our general intelligence has long been decreasing. Since about 1997, we have actually seen a ‘Negative Flynn Effect’ in many Western countries and this is on general intelligence. So, the environmental Flynn Effect was cloaking an underlying genetic decline in our intelligence, we reached our ‘phenotypic limit’ on the specialised abilities causing the Flynn Effect, and the underlying genetic decline began to be seen even on the IQ tests, it having long previously been observed on more objective measures, such as reaction times, which have been getting longer since 1880. [Editorial note; see Professor Richard Lynn’s incisive analysis of the Flynn Effect, in chapter 8, Dysgenics; Genetic Deterioration in Modern Populations, 1996].

Superior is riddled with factual errors: Darwin’s 1871 book The Descent of Man ‘(swept) away these religious creations myths’ (p.55). No. That was his Origin of Species. ‘We know the brains of hunter-gatherers are no different from those of anyone else’ (p.57). Incorrect. At the very least we know they are smaller on average than those of groups who have adopted farming, as Richard Lynn has shown in Race Differences in Intelligence. Apparently, according to Italian geneticist Luigi Cavalli-Sforza ‘there are races, except the number of them is practically endless’ (p.101). Not so. He reduced his data down to about 12 genetic clusters, which fairly precisely paralleled the 12 races of classical anthropology.

‘Gerhard Meisenberg, [is] the current editor in chief of Mankind Quarterly’ (p.104). Not true. This reviewer is the editor-in-chief, as is clearly stated on the journal’s website. Saini considers this journal racist and a conveyor of extremely poor quality research. Yet an article about Tatu Vanhanen, published in Mankind Quarterly, is the source for her discussion of the Finnish political scientist (p.304). Saini claims that we have next to nothing genetically in common with more distant ancestors. But J. Philippe Rushton’s research has shown that we tend to sexually select for an optimum level of genetic similarity, meaning we can be quite genetically similar to relatively distant ancestors.

‘But to date, no scientific research has been able to show any average genetic differences (between races) that go further than the superficial and are linked to hard survival . . .’ (p.183). Au contraire, there is a massive body of literature on race differences in the prevalence of partly and entirely genetic disorders as well as race differences in responsiveness to different medicines, some of it summarised in my book Race Differences in Ethnocentrism. In chapter eight, Saini ‘debunks’ this idea on the grounds that some outliers from some races respond differently to a given medicine than do the majority. But there will always be outliers. If the author ever requires a kidney transplant, would she like a doctor to insert a kidney from a South Asian donor or from a black donor? How ‘superficial’ will race differences seem then?

Saini maintains that ‘skin colour’ is ‘superficial.’ It is not. It relates to the ability to absorb Vitamin D from the sun, it reflects testosterone levels (which relate to personality), and much more. She states that perceptions of physical attractiveness are ‘obviously a value judgement’ (p.176). Yet there is a voluminous literature showing that attractiveness can be linked to evolutionary fitness (see J. Philippe Rushton, Race, Evolution, and Behaviour: A Life History Perspective).

J Philippe Rushton

‘This is the book I have wanted to write since I was ten years old, and I have poured my soul into it’ (p.293). When Angela was ten years old, ‘boys from my school threw rocks at me and my sister . . . telling us to go home.’ This appears to have traumatized Angela, or at least left her resentful with ‘that cold lonely feeling of not quite being able to fit in . . . the British National Party was marching outside our door . . .’ (p.164). During the Brexit Referendum, Angela’s childhood borough of Bexley was one of only 5 of the 32 London boroughs to vote Leave: ‘we also knew that a sizeable slice of voters wanted fewer of us (non-whites) there in the first place’ (p.165). In other words, the author has a massive chip on her shoulder about ‘race’ and her childhood experiences, which she relates to ‘race.’

To make matters worse, she hints at some kind of family rift, relating to race. Her Hindu mother, Santosh Gupta, married a man of a different ‘caste, religion, and community’ (p.215), Sohan Saini, in Redbridge in Essex in 1979. Angela’s book’s dedication reads, ‘For my parents, the only ancestors I need to know.’ It is hard to believe that anyone with any love for their grandparents could write such a thing, and apparently Angela’s mother was raised to strongly believe in the caste system (p.215). This level of emotional investment makes Saini one of the least suitable people to write an objective book on the subject of race. ‘Race’ invokes such strong emotions that she simply cannot think logically about it. In addition, she implies that as the daughter of immigrants, she was pressured, to some extent at least, to study a subject which led to a high-paying job – in her case Engineering (p.281) – so she may well have ‘issues’ with science: she characterises human directed evolution, which as a child of high caste parents she is an extreme product of, as a ‘cold, calculated way of thinking about human life’ (p.71).

These problems aside, we gain insights into how Angela Saini thinks. In essence, it is morally wrong to engage with the concept of ‘race’ and those who do so need some ‘self-examination,’ should feel ‘regret’ and ‘remorse’ (p.84) and may well suffer from ‘an absence of introspection’ (p.85). ‘Nothing is more seductive than a nice string of data, a single bell curve, or a seemingly peer-reviewed scientific study,’ she tells us. ‘After all, it can’t be “racist” if it is a “fact”’ (pp.132-133). Reading between the lines, Angela is saying that if science makes reality seem unpalatable, and makes you question whether all humans are equal, you should conclude that the science is wrong – and only then are you ‘moral.’ Despite what science ‘seemingly’ says, you must have faith.

The world is divided between ‘good’ – Angela’s army – and evil. This bespeaks what American psychologist William James called the ‘religion of the sick soul.’ This perspective tends to be held by neurotic people, those who feel negative feelings strongly, as the author did after listening to an Australian Aboriginal woman’s tragic story. ‘I don’t cry easily [she remarks]. But in the car afterwards, I cry for Gail Beck’ (p.22). Neurotic people need a structure in a frightening world of uncertainty and the ‘religion of the sick soul’ provides them with this: I am in the good group, not the evil group, and I must fight evil.

Accordingly, ‘well-meaning people,’ with spotless credentials, such as Cavalli-Sforza, can be forgiven for making fact-based ‘incendiary statements’ (p.157), because they are ‘one of us.’ If Harvard geneticist David Reich asserts that races might exist, then these are ‘words I never expected to hear from a mainstream respected geneticist’ (p.182) and he may need to reflect that he is using ‘similar frameworks’ to Francis Galton and other evil people (p.151). Those in Angela’s Army are always trusted or given the benefit of the doubt, as we always hold our in-group to lower standards. If someone on Angela’s side describes race research, as University of Washington psychologist David Barash does, as ‘a pile of shit’ then this doesn’t imply that he’s emotional or biased. He is one of the righteous and thus unimpeachably logical.

University of Virginia psychologist Eric Turkheimer tells Saini that intelligence is totally down to environment – despite twin studies stating it’s at least 50% heritable (p.155) – because his study of deprived children found that almost all IQ variance was down to environment. It doesn’t occur her to say, ‘Hang on! It’s been shown by Princeton economist Gregory Clark in The Son Also Rises that socioeconomic status is 70% heritable across generations, and by looking at the very poor you’re massively limiting the genetic variance!’ Turkheimer is on Saini’s side, so he must be right.

Saini finds it ‘paradoxical’ that many of those involved in The Mankind Quarterly are from such countries as Saudi Arabia and Japan (p.115). The simplest explanation, of course, is that those who write for the journal are not ‘white supremacists’ but simply scientists who won’t be straightjacketed by neo-Marxist ideology.

Related to the author’s Manichean world view, she does exhibit genuine kindness or, as it’s termed in psychology, agreeableness. She frets for the future of her son (p.294). She expresses guilt for her own occasional feelings of ethnic pride (p.239), most clearly seen in her first book Geek Nation in which she seems to imply that Indians are innately good at science.

According to Simon Baron-Cohen’s study ‘The Male Brain Theory of Autism,’ one aspect of autism is that you are very intensely focused on systematizing and very bad at empathising; empathy being a key component of agreeableness with empathy clustering together with altruism. These people are more likely to be male. At the other extreme there are those who are superb at empathising but dreadful at systematizing. These ‘system-blind’ people are more likely to female.

Some forms of schizophrenia take this to an extreme. David Badcock, in his 2003 study ‘Mentalism and Mechanism’ explains that empathy involves the ability to ‘mentalize’ – to read internal states from external cues. Schizophrenics are so obsessed with mentalizing that they over-detect these cues and read too much into them: a smile is a sign of being in love; a frown implies somebody wants to murder you. This, of course, makes them paranoid. They see evidence of conspiracies everywhere; there are dark powers behind all that occurs, nothing is what it seems. People who are within the mentally healthy range and who are altruistic, and so expected to be high in empathising (even if they can also systematize), will think like this in a diluted form. This is what they call “Angelism” in France.

Concerning multiculturalism, agreeable people are more likely to conform while, as Michael Woodley of Menie has posited with his Cultural Mediation Hypothesis, normal range intelligence is associated with dominant ideological conformity, because intelligence predicts the effortful control needed to force yourself to believe something that it is beneficial to you to believe. And it is ultimately beneficial to conform.

So the fact that our view of Neanderthals has changed so that we now think that they were more sophisticated than we once thought isn’t an example of opinions changing in the light of new evidence. The change occurred because white people were found to have had a small percentage of Neanderthal DNA. If that had been found among Aboriginals, then no such change would have taken place (p.168). Racist scientists keep trying to find some way of proving the reality of race, they will always find some new method (p.292), it’s not that they are simply presenting the simplest theory, and if they are then the peer-review process must be corrupt in their favour (p.133).

People ‘debunking’ the empirically inaccurate statement that Cheddar Man had black skin are not trying to get to the truth, they are ‘far right’ (p.167). Ditto Gerhard Meisenberg, when he asserts that cleverer people tend to leave Pakistan and that this will damage their economy. ‘At a stroke [Saini avers], he condemns without evidence all the world outside Europe and parts of Asia to genetically inferior status’ (p.106).

Angela Saini lives in a black and white world of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in which disagreeing with her about race constitutes the Mark of the Beast. In her acknowledgements, unambiguously ‘good’ scientists, such as Eric Turkheimer, are thanked for helping her, while even the ‘well meaning’ Doubting Thomases are subject to her pointed ingratitude. Dedicating the end of this section to her son, Aneurin, she tells him that the ‘content of our characters is entirely in our hands. Don’t forget that, my baby.’ So, we are independent of environmental or genetic influence. We have absolute free will, like souls transmigrated into bodies.

Angela Saini is what Bruce Charlton and I, in our book The Genius Famine, call the ‘Head Girl.’ Altruistic, socially skilled, highly intelligent; the South Asian who made her way from a poor area of London to Oxford University. But the problem is that she has been traumatized by ‘race’ and so she can’t analyse it logically. She has been sucked into the latter day Puritanism of Multiculturalism. And she’s not sufficiently conscientious to do the in-depth research that might open her eyes to the anti-science ideology with which she has been inculcated.

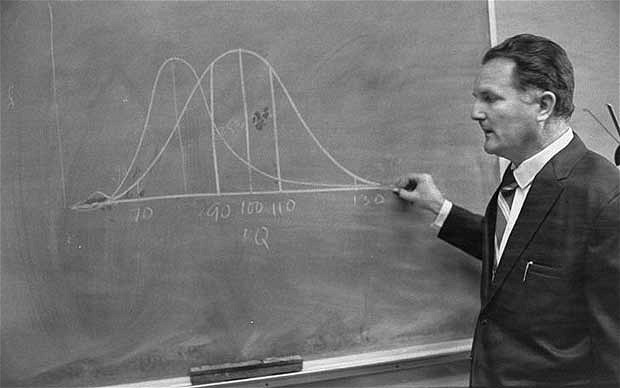

Arthur Jensen, credit Daily Telegraph, Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image

Dr Edward Dutton is an independent researcher and Adjunct Reader in the Anthropology of Religion at Oulu University in Finland. He regularly vlogs at The Jolly Heretic: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCMRs0Ml8RF0cWVAOeQeBxTw

The fact that Angela Saini mixed up Darwin’s “Descent of Man” and “Origins of Species” in a citation is a big error. Presumably she has interns and a staff of editors. And like Edward Dutton points out, that’s not the only blatant error in the book.

Just as hilarious, she blasts Mankind Quarterly as racist, yet cites and MQ article to back up her thesis?

If you’re going to be a snooty academic, looking down your nose at us working class whites, you ought get your facts straight at least.

Eric Dondero, Editor

Subspecieist.com

fmr. Snr Aide, US Cong. Ron Paul

I had hoped Ed Dutton would refute this convenient “encrapsulation” of all the familiar fallacies of “unscientific anti-racism” which was accorded respect by the “New Scientist” and other toadies of the dominant “race, gender, class” ideology. I await the response, if any, of the Galton Institute now led by anti-racist activist Ms Talmud. I had to resign my Fellowship of the Royal Anthropological Institute because its stuff became unbearable. Medical genetics will prove a way back in, but the general oncoming darkness will need an effort to keep bright lights on wherever possible: look at the experience of Watson, Duchesne, Carl and others gone before.

See the recent features on Itzkoff and on Lynn in “American Renaissance”.

Thank you for publishing this review.

Saini’s book, it seems, fails to ground, defend, or justify any answer to the only truly important question facing us in this timely dispute, which does not concern whether races exist or not. The important question, the urgent question is whether the best regime ????? to use the results of medical & zoological research to help develop higher, healthier, better breeds of human beings or not. We are already willing to do so within accepted ??????????? limitations. This is a very old question & our sciences have added nothing to its solution. Sokrates himself proposed a natural program of eugenics in The Republic. Xenophon on occasion spoke of men in light of the breeds of horses or dogs. The famous example of Sparta is well known. This manner of speaking is not much liked today, because we dogmatically prefer the received egalitarian answer: ???????? or controlling superior human breeds is said to be categorically wrong. But this has never been proven (and reference to the insanities of the Nazis is irrelevant). It is a bare assertion having no authoritative weight. The people who normally embrace this dogma are usually so irrational that they are also self-contradicting ????? & ???????? ???????????. It is no accident that this book was written by ? ????? of non-Western descent, as every reader of ordinary common sense can easily perceive. She comes from a people who was conquered & colonized; she bares all the marks of a manumitted but once servile people, and member of the weaker sex to boot. Her supposedly “scientific education” is shown in this article to be a fraud, & her grossly vulgar ignorance of the higher humanism or philosophy is nauseating. Her kind ???? ??? ?? ??????? ?? ??? ?? ??? ??? of serious questions & questioning. It leaves one wondering what justifies attention to so bad a book by such a worthless ephemeral writer. The true final contemporary question concerns whether the breeding of a morally & intellectually higher breed of man of a ruling type is the appropriate way forward politically & scientifically into the future or not. The only way to answer this question is by a fresh confrontation with the greatest minds who have already faced this issue in relation to man’s highest objectives, with a view to the religious question, & with continual reference to the political regime. The time has once again come to ask the question which, since Plato, has raised all those who confronted the fundamental issues toward the peaks of human thought. What is the relative rank of aristocracy and democracy and which regime is more choice-worthy and why? What is the best kind of aristocracy and how must we strive for it? Even people of mediocre capacities can see that mass modern democracy buttressed by commerce and modern science is failing. Malignant herd-like despotisms in the East are now rising and threatening. The West has within itself the means to re-found its purposes. These are great times to which we must rise. We must be grateful. The greatest minds are at our disposal; they have generously given us the best means to light our way into the future, so pregnant with danger & dreadful surprises.

The problem is getting to yes. The egalitarian politics and entertainment carry on regardless, with individual resisters “excluded”. Watch TV and read “The Guardian” for sufficient evidence. Disability has become an entitlement and a cult. The genetic basis of stupidity is denied. The carapace on the decadence needs to be lifted like a scab on a poisoned wound, so that healthy flesh can grow again.

Let us look again at Julian Huxley, Cedric Carter, Raymond Cattell, Richard Lynn, John Glad, even H. G. Wells and the “Marxists” like Herman Muller. Controlling evolution is a humanitarian not a malign objective, in the right hands, for the right purposes and by the right methods, preferably Western not Chinese.

Marc, I can think of a few “feminists” whose lack of visible “femininity” has not been much of a handicap, including Old Mother Attwood, and there is the ubiquitous Memsahib Alibhai-Brown, who always looks as though she has swallowed a lemon, whether she is describing her English subjects as “poor dears” or announcing her desire to see “white men” eventually disappear. But you may have point – Afua Hirsch, for example, is quite attractive.

Angela Saini features again in the BBC4 programme vilifying eugenics on 3 October. For those who cannot get enough of “Hitler” and “Holocaust” on the telly, this is their special treat. “Non Angli sed Angeli,” or in this case, Photogenic not Eugenic.

Pingback: Outliers (#73)

Pingback: Carte mondiale des QI : l’article de Libération a-t-il une valeur quelconque ? – Le blogue d'Obiter