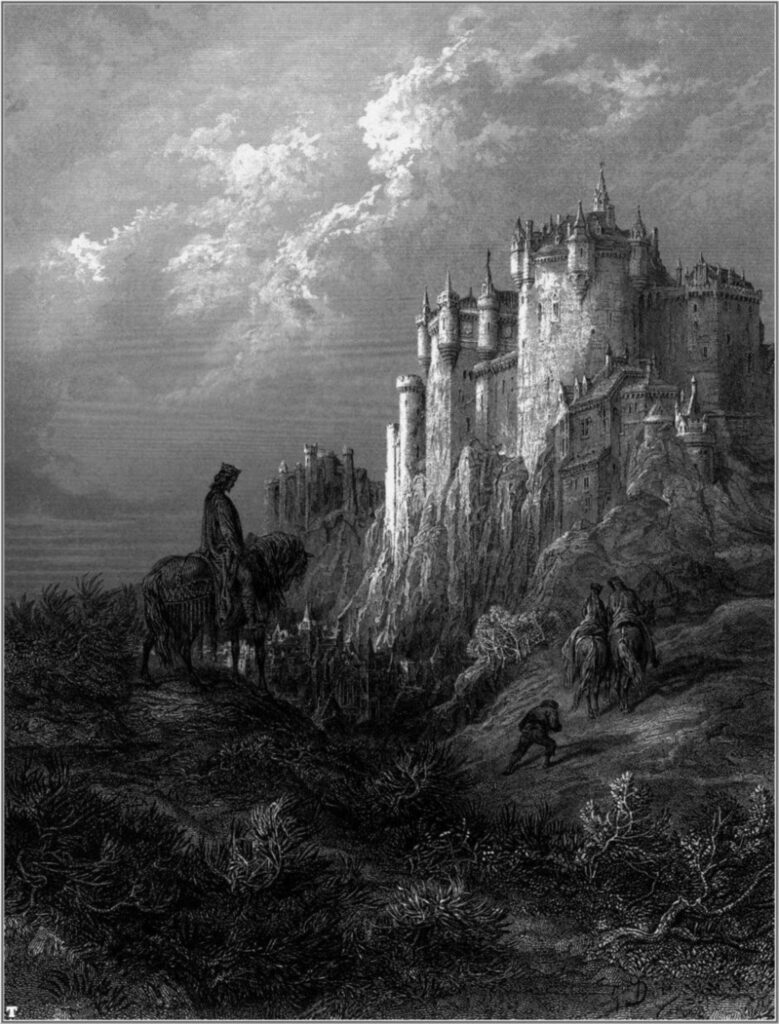

Gustav Doré, illustration for Idylls of the King, credit Wikipedia

Endnotes, August 2023

In this edition: English music for strings at JAM on the Marsh Festival; songs by Eric McElroy; reviewed by Stuart Millson, the Classical Music Editor of Quarterly Review

Still preserving a sense of rural remoteness, Romney Marsh in Kent is one of the country’s most unusual localities. Once a watery world of creeks and salt marsh, then drained and given over to crops and sheep-grazing, the green low-levels extend as far as Dungeness and Denge Marsh, a unique shingle promontory jutting into the English Channel ~ and designated as our nation’s only official desert. The scene is partly dominated by the atomic power station, which is linked to its sister-facility in the North-West of England, by way of a single-track railway line (spared by Beeching) that threads its way through the hamlets of the Marsh. The tower of Lydd Church provides a contrast to the austere atomic monolith on the Ness; and rising above the landscape just to the east is the equally impressive Church of St. Nicholas, New Romney ~ the venue for a London Mozart Players concert of English (and American) music for strings, held as part of the JAM on the Marsh Festival.

JAM stands for John Armitage Memorial, commemorating a far-seeing patron of the arts who saw the necessity of blending music of the past and present, with new commissions to build the repertoire; and a mixture of local, national and international performers to make music in the landscape that he adored. Sarah Armitage now continues his great mission, with conductor Nicholas Cleobury acting as ‘Curator’ ~ and on the occasion of the 15th July, taking up the baton to bring a capacity audience works of Elgar (Serenade forStrings), Samuel Barber (Adagio), Vaughan Williams (Tallis Fantasia) and Sir Michael Tippett. And to underline the idea of championing imaginative new music, Nicholas Cleobury included in his programme a piece by James Aburn ~ a composer still in his 20s.

Entitled Silent Shadows, James’s inspiration came from the legend of supernatural marshland light (the ‘will-o’-the-wisp’ phenomenon) said to have confused travellers on lonely lanes; leading them, not to a welcoming farm stead, but into the sinister boggy darkness. Played with enormous commitment by the London Mozart Players, the work proved to be tonal and accessible, but with growing touches of tension and an evocation of the surrounding light and landscape: a worthy successor to the intensive string-writing of Britten and Tippett. And it was Tippett’s masterpiece, the Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli which followed: a great, single span, elaborating on the baroque composer’s melodies of 300 years gone by, yet drawing them firmly into the 20th-century, and suffusing them, too, with echoes of Tudor England.

For example, just after a particularly knotty section, close to the end, in which tension builds to an almost unbearable strain and stress, Tippett seems to draw back ~ releasing a great sigh of relief, with a tune that could almost have come from The Lark Ascending. And yet this is not music of the southern Downland, walled gardens or the Cotswolds. Instead, Tippett paints a more obscure scene: the England of rough hedges all hewn into weird shapes by endless gusts of sea-wind, and garlanded, not by roses, but by sea kale and viper’s-bugloss. In fact, the perfect music for St. Nicholas, New Romney, which on that sunny Saturday in July, still withstood a strong breeze from the seashore, some two miles away as the crow flies. Music-lovers who crave the right setting and atmosphere for their orchestral and choral passions will find it all here, at JAM on the Marsh.

The CD label, SOMM Recordings, is also doing much for new music, having recently issued a compendium of songs by Eric McElroy (born 1992): cycles based upon poems by Gregory Leadbetter, Alice Oswald and Robert Graves.

Eric McElroy ~ active as a composer in North America and England ~ takes us to the Balearic coastline known by the emigre English poet, Robert Graves, but listeners should not be deceived into thinking that we are entering a soundscape of sangria-sipping sunny romanticism. McElroy goes back to Graves’s experiences on the Western Front, setting:

‘Gulp down your wine, old friends of mine,

Roar through the darkness, stamp and sing

And lay ghost hands on everything,

But leave the noonday’s warm sunshine

To living lads for mirth and wine.’

A more tavern-type, earthy feel exists in the song, Strong Beer ~ leading the listener to think that we may have gone back to settings of Belloc by those imbibing composers of the ‘20s and ‘30s, such as Peter Warlock. Yet McElroy avoids the trap of jaunty tunes. His is a more angular, abstract style, perhaps reminiscent of Britten’s intensity and austerity. Tenor, James Gilchrist, sings:

‘Crags for the mountaineer,

Flags for the Fusilier,

For English poets, beer!

Strong beer for me!’

An unusual album, in that we do not often find such extensive modern settings of poetry quite of the Graves era. The composer states in the CD booklet: ‘We sing ourselves into being. The self is to be found not in the song but in the singing.’

Endnotes, special additional report by Dr. David Green of the English Music Festival and Elgar Society on this year’s Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester Cathedral.

Randall Svane, Quantum Flight

Randall Svane is a distinguished American composer who writes music for many different media, including large orchestral pieces such as the one we heard at the Three Choirs Festival on Tuesday 25th July. Incidentally, he was also the composer for the musical setting of the Responses for the Wednesday afternoon Three Choirs Choral Evensong. This was broadcast live on BBC Radio 3.

The orchestral work we heard that evening was named Quantum Flight and according to the composer the form of the piece is related to quantum mechanics, where the stability of an atom with revolving electrons may be disturbed such that then revolving electrons move different orbits, either releasing or absorbing energy. True to this description it was certainly an energy- intensive and electrifying opening to the concert with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO) and the Gloucester Festival Director and conductor, Adrian Partington, in exceptionally good form. After the intense and electrically-charged opening, there was short period of meditation prior to the climactic conclusion. The work was slightly less than the programmed five minutes and I am sure that we would have appreciated a piece of much longer duration.

Arnold Bax, Tintagel

Bax was the consummate orchestrator of his generation of British composers. In a fine performance as we heard at this great Festival, we can only wonder at his incredible facility in this department. The combination of superb orchestration and wonderful tunes in Tintagel make it probably his most popular orchestral piece. This despite the fact that he also wrote several concertos and seven symphonies! (eight if you include the early Spring Fire). There has always been a dispute as to the real inspiration behind the work. Was it the developing intense personal relationship with the pianist Harriet Cohen possibly consummated on their visit to the ruined but spectacular Arthurian castle on the Cornish coast? Or was it simply reflecting the aspect of the sea when being overlooked from the castle on a “sunny but not windless summer day” ~ Bax’s own description during that same visit with Harriet Cohen in 1917? Bax completed the work in 1918 the same year he asked his wife for a divorce, which was refused!

One of the most difficult aspects of a performance of Tintagel is to get the timing of the various sections right and clearly this has caused some debate with previous conductors from Sir Eugene Goossens who in his 1928 recording managed to complete it in only 12 minutes, to Sir Mark Elder in a performance recorded fairly recently which takes 17 minutes. Obviously great opportunities for the conductor! I’ve always preferred the pace that Sir John Barbirolli took with the work, at 15 minutes and this is exactly the same time that Adrian Partington and the RPO delivered at the performance.

However, I did feel a little short changed by the lack of power of the horns at the climax of the work. That might have resulted from my position at the front of the nave where the horns are not visible and thus not so audible. That aside, one really couldn’t fault the performance of both the RPO and the conductor and, not surprisingly, the piece received tumultuous applause.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Why this new format of GIANT LETTERS, Ed?

How many readers are optically alternative?