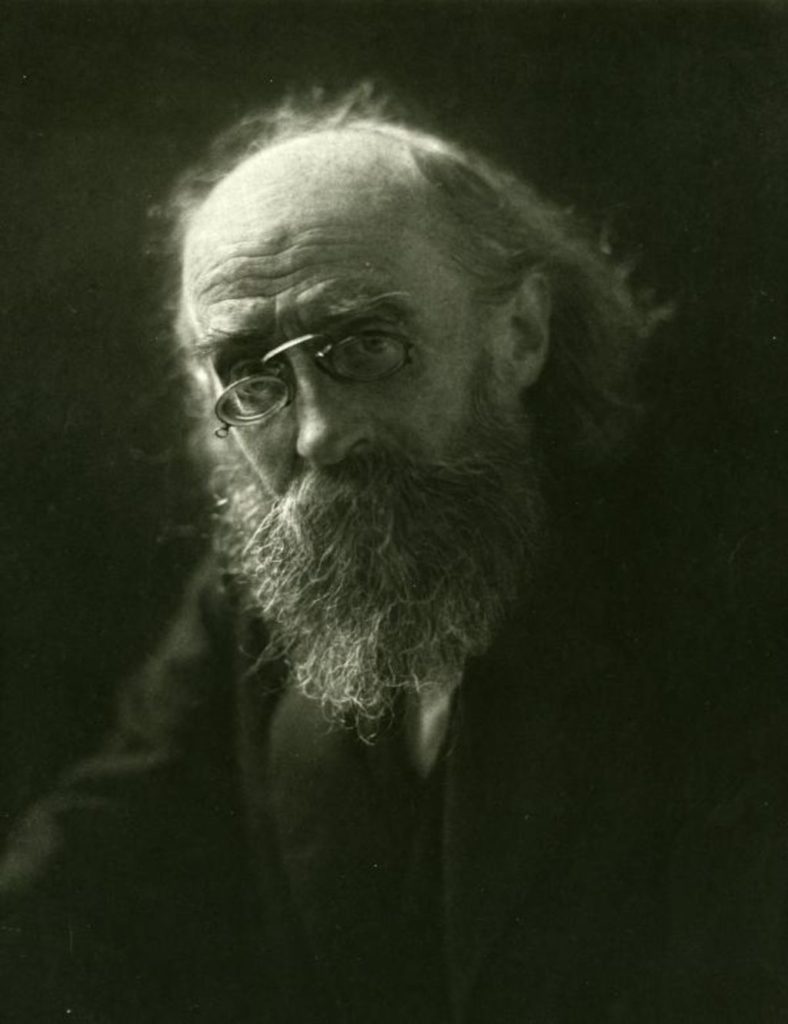

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany.

Eisner’s Choice – Reform or Revolution?

Kurt Eisner, a Modern Life, Albert Earle Gurganus, Camden House, 2018, HB, 576 pp., reviewed by LESLIE JONES

Kurt Eisner, a Modern Life, is a fitting title for this compelling biography of the campaigning journalist and critic. Eisner led the bloodless revolution in Bavaria in November 1918 that toppled the Wittelsbach dynasty, thereby “effectively ending both the Second German Empire and the First World War” (p. 2)*. According to the Marxist historian Arthur Rosenberg, Eisner’s objective as head of state of the Bavarian Republic, until his assassination on the 21st of February 1919, was “…the execution of a radical bourgeois revolution…to bring down the military power and dynasties, to secure immediate peace, and to enable an effective democracy…” (Rosenberg, cited p. 440). At least 100,000 mourners followed his funeral cortege.

As Thomas Mann prophetically commented in a diary entry dated November 8th 1918, “Both Munich and Bavaria governed by Jewish scribblers. How long will the city put up with that?” Eisner’s assassin, Lieutenant Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley, considered himself “a loyal monarchist until death!… [and] a loyal Catholic”. “I hate Bolshevism!”, he proclaimed in his testament, “I hate the Jews!” Profound historical forces placed Eisner and Arco-Valley on collision course. Eisner, a secularised Jew and an incisive critic of Weltpolitik and of Prussian-Junker militarism, personified German modernity. His nemesis, conversely, personified monarchist Bavarian politics. He commanded the 5th company of Freikorps organizer Colonel Franz von Epp’s Bavarian King’s Own Regiment.

Eisner was born in Berlin on the 14th May 1867. His father, the merchant Emanuel Eisner, provided military regalia to the Russian Imperial Court and later to the Prussian emperor and king. Kurt’s family clearly had the wherewithal to provide him with a classical education at the Askanisches Gymnasium. He subsequently studied philosophy and literature at Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm University. At the age of nineteen, he confided in his journal, “I no longer care to believe in a dear God”. He worked on a doctoral thesis (never completed) entitled “Achim von Arnim as Publisher, Adapter, and Imitator of Older German Poetry”. He was increasingly drawn to journalism and the theatre. He considered the latter a potential way of enlightening the masses. In January 1890, he a became an editor and correspondent of the Herald News Agency, and then in Autumn 1891, copy editor for the left Liberal Frankfurter Zeitung. A succession of prestigious posts followed, notably that of “principal editor” of Vorwärts, the Social Democratic Party newspaper, from 1900 to 1902.

The author, Professor Emeritus of Modern Languages at The Citadel, points out that “Eisner embodied everything the Nazis’ Blut-und-Boden (blood and soil) populist, racist nationalism opposed” (p. 5). He called the German military a “bodyguard to the privileged classes” and in “Militarism” (1893) he warned that “The great world war of the future is in its cave crisping its claws”. Within the Social Democratic Party, a faction associated with the trade unions supported social imperialism. According to Eduard Bernstein, the German worker would benefit economically from the acquisition of colonies. Eisner was an outspoken opponent of this theory. Imperialism in his judgement was not only immoral but “would inevitably lead to a cataclysmic international war” (p. 112). A trenchant critic of German autocracy, he believed that it was “the root of the nation’s evils”. An article for Der Kritik, January 2nd 1897, entitled “An Undiplomatic New Year’s Reception” (signed Tat-Twam), earned him his first prison sentence, for the offence of lèse majesté.

Concerning Eisner’s weltanschauung, in Psychopathia Spiritualis: Friedrich Nietzsche und die Apostel der Zukunft (1892), Eisner portrayed Nietzsche as misogynistic, elitist and anti-Semitic. En passant, he dismissed racial determinism and the individualist variant of social Darwinism elaborated by Herbert Spencer. Capitalism was inherently anarchic and unstable, in his view, whereas socialism was rational and ultimately ethical. As the political editor of the General-Anzeiger, from 1893 to 1896, he was profoundly influenced by Professor Hermann Cohen, doyen of the neo-Kantian Marburg School. Eisner’s socialism (like that of Bernstein) always contained a Kantian, ethical dimension, in contrast to that of the “scientific” socialists who had “made their way to Marx via Hegel” (p. 25).

For Cohen, whereas the power state (Machstaat) represents the interests of particular groups, the legal state (Rechstaat) represents those of the whole community. Members of the Prussian Landtag, for example, were elected by a three class suffrage system that guaranteed its domination by the Junkers. Cohen contended that the Social Democratic Party was the best vehicle to transform Germany into a democratic, legal state but that violent revolution was immoral and inimical to the greater good. Eisner inferred from Cohen’s teaching “the ineluctability of social justice through increased democracy” (p. 38). Eisner – the Kantian socialist. Can we discern here the ultimate cause of his failure as a revolutionary, namely, his reluctance to countenance violence? Lenin and Arco-Valley had no such qualms.

In the bitter, fin de siècle debate in the SPD between reformists and radicals, the former favoured ending the electoral boycott of the Prussian Landtag and putting forward candidates or supporting Left Liberals. The latter group, which included August Bebel, Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg and Franz Mehring, regarded parliamentarism as a snare and upheld the primacy of the general or political strike. On this issue, Eisner sided in practice with the reformists, while paying lip service to the notion of revolution. He agreed with Bernstein that “the worker’s movement …had broken the chain of events Marx foresaw” (Eisner, cited p. 233).

In the 1907 election, the SPD was depicted by Chancellor Bülow as unpatriotic, in view of its opposition to Weltpolitik. Its tally of deputies fell from 81 to 43. The author detects in this electoral reverse the origins of the party’s subsequent shift to the right, which in August 1914 would “situate Social Democracy squarely in the nationalist camp…” (p. 202).

Like Bernstein and Kautsky, Eisner initially considered the war as defensive, a response to Russian aggression. In 1913, he had been persuaded by Adolf Müller, editor of the Münchener Post (Eisner was then its associate editor) that Russia intended to attack Germany. At a peace rally in Munich on 27th July 1914, accordingly, Eisner depicted Serbia not Austria as the aggressor and as “the instrument of Russia”. He urged all German socialists to vote for war credits, if Russia attacked Austria-Hungary, “for none of us wants Cossackdom to rule Europe” (Eisner, cited p. 308).

Perusal of the German Government’s “white book”, published on 3rd August 1914, which blamed the Entente for the war, convinced Eisner that he had been “duped and manipulated” (p. 311) and that Germany was the aggressor. He was expelled from the SPD in January 1917 and subsequently joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). In 1918, he passed compromising secret state papers to the press that established Germany’s war guilt in 1914, in the vain hope of moderating the Entente’s peace terms. Eisner thereby gave sustenance to the fateful myth of the stab in the back (dolchstosslegende). He even advocated forced German labour to reconstruct France.

In 1933, the Nazis removed Eisner’s remains from the Ostfriedhof in Munich and destroyed the contiguous Monument to the Revolution.

Kurt Eisner

* Editorial Note; all quotations are the words of A E Gurganus, unless otherwise stated

Dr Leslie Jones is the Editor of QR

Was Nietzsche actually “antisemitic”?

Just like almost everyone from ancient Egypt to the Labour Party, according to David Nirenberg’s latest contribution to the subject? I don’t suppose he ever compared Israeli military actions to German ones which is part of the New International Definition of “antisemitism”.

Is Humpty Dumpty now Big Brother?

You don’t need to read Hugo Drochon’s article in the latest “New Statesman” to know that FWN’s aphoristic and self-correcting themes have been mined and (mis)appropriated, by nazis and antinazis; modernists and postmodernists; atheists and occultists; Walter Kaufmann, Jacob Golomb and Robert Holub; Bill, Ben & the Flowerpot Men.

He is not easy to read but needs to be read neat, albeit with some background knowledge of his times if not of his sister.

Is each and every single perspective labelled “antisemitic” ipso facto false and/or irrational and/or evil? Where would that put (say) Bernard Lazare, Theodor Herzl, Hannah Arendt, Jerry Muller, or Shlomo Sand? Discussions among Jews are always interesting and usually erudite, but can others sometimes join in?

I am Ruth EISNER Bramer, Grand-daughter to Kurt Eisner. I enjoyed the review of the book written by Professor Gurganus. It is a factual account of my grandfather’s life, based in part on the life-long research of my sister, the late Dr. Freya Eisner. There is one glaring mistake in the review as presented. the picture of kaiser wilhelm has no place in the review! He was a member of the Junker class, reviled and despised by Kurt Eisner. That picture is not in the book reviewed. I humbly and earnestly ask you in the name of each member of the Eisner Family to remove this gratuitous insult from your review and replace it with a picture of Kurt Eisner.

There is a lovely collection of Eisner pictures on Google Images, but the most handsome ones seem governed by copyright.