Benito Mussolini, Bundesarchiv Bild 102-08300

Cesare Bourgeois

John Gooch, Mussolini’s War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse, 1935-1943, Allen Lane, London, 2020, maps, illustrations, bibliography, notes, index, pp.vii-xxiv + pp.1-410, ISBN 978-0-241-18570-4, review essay by Frank Ellis

Fidarsi è bene, ma non fidarsi è meglio

How could it be that a nation one of whose most illustrious sons gave the world Il Principe (The Prince, 1532) and Dell’arte della Guerra (The Art of War, 1521) could, in turn, have produced a leader, who allowed himself to get swept away with dreams of imperial neo-Roman glory, whose incompetence transformed Italy into a vassal of Germany and led the country to defeat, humiliation and destitution? Part of the answer lies in the nature of power. Those who wield power want to expand its range and one way to achieve this aim is by suppression of domestic opposition and by pursuing wars abroad, behaviour which is certainly not confined to authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. Revolutionary regimes – and Fascist Italy and National-Socialist Germany were, in essence, revolutionary not reactionary – are driven by an impulse to remake their states and the world in a hurry. Wars of conquest and territorial expansion are the chosen means. Better still, external wars can also be used to justify greater control over the lives of citizens (pandemics can serve the same purpose). Further, war expressed one of the core ideas of Fascism and National Socialism: the necessity and nobility of permanent struggle.

An obvious preliminary in a book dedicated to the wars of Fascist Italy – one not satisfied by Gooch – would be to consider what constitutes the nature of Fascism and how it shaped Italian foreign policy under Mussolini. This is important since it would discriminate between Fascism (Italian or Spanish) and National Socialism, eliminating the propagandistic conflation of the two and would serve to distinguish Fascism from the more aggressive and successful manifestation of National Socialism. Clear differences, for example, emerge in the way the two states prepared for, and executed, their military campaigns and how they fought when the tide turned in favour of the Allies. For an ideology that placed so much faith in war and struggle as a part of statecraft, there was a definite mismatch between Fascist theory and real-existing Fascism.

In National-Socialist Germany, ideology and military success reinforced one another. In matters military, Il Duce and his regime were defective. Unlike its far more lethally efficient relative to the north, Italian Fascism failed to inspire the same consistently high levels of military success and skill and so failed to satisfy its own martial criteria.

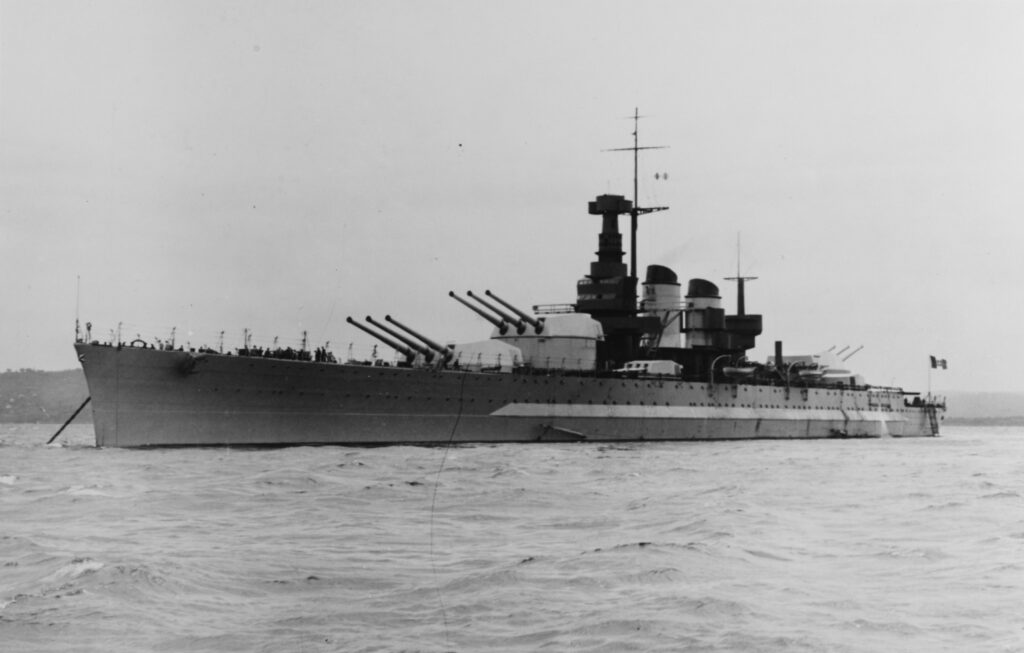

Before the start of WWII, Italian forces had fought in the deserts against tribal formations in Libya, overrun the forces of Haile Selassie (Negus) in Abyssinia and went on to provide valuable assistance to Franco during the Spanish Civil War. During WWII, Italy was again heavily deployed in the deserts of North Africa, this time against British and Commonwealth forces. Eager for glory, Mussolini sent his armies into Greece where they very soon encountered effective resistance. The occupation of Yugoslavia turned into a counter-insurgency quagmire, and taking part in Hitler’s crusade against the Soviet Union proved to be an utter catastrophe. In the Mediterranean, Mussolini’s war was essentially a naval war and the Italian navy (Regia Marina), bolstered by the recent addition of two 35,000 ton battleships, the Vittorio Veneto and Littorio, posed a serious threat to British operations. The considerable potential of Italian naval assets was, however, never fully realised, essentially because they were deployed too defensively, and were, in the main, commanded by men who lacked the aggressive ethos of the Royal Navy.

Vittorio Veneto

In Libya, the main opponents were the Senussi tribesmen who were tracked from the air, sometimes gassed, hunted down and killed. Following the earlier Spanish and British examples, the Italian occupation regime set up concentration camps – though Gooch for some reason refers to them as ‘internment camps’[1] – into which non-insurgent tribesmen were corralled, so separating them from the armed insurgents. By the end of 1930, 80,000 non-combatants were in these camps, which would have included women and children. One can take it for granted that many of them perished from disease and starvation, almost certainly in excess of the 25,000 Boers who are known to have succumbed in British concentration camps.

By the end of January 1932, Libya was once again under Italian control. Attention now turned to Abyssinia. Operations here were far more demanding, but Italian planners mastered the challenges. Good use was made of sigint and aircraft, and motorised units were deployed to great effect. The huge logistics effort in harsh terrain was especially impressive. Thus, port capacity at Massawa on the Red Sea was increased from a low point of 400-500 tons a day to eventually 4,000 tons a day. Between February 1935 and July 1936, the Italian navy transported nearly 600,000 men, 635,000 tons of supplies, just over 10,000 vehicles and 41,000 animals. By the time land operations were ready to begin, just under 50,000 tons of fuel and lubricants had been stockpiled along with 14,500 tons of munitions. This impressive logistics effort continued after the war had started. As Gooch notes, ‘The success of the Tigray operations owed a great deal to (sic) skill and effectiveness with which the Italian Intendenza had managed the logistics. Five army corps had been kept supplied in mountainous regions lacking any resources more than 400 kilometres from the coast and 4,000 kilometres from the Italian patria’.[2]

Other noticeable features of this campaign were the use of gas shells, the systematic destruction by Italian forces of any assets and infrastructure on the Somalian highlands that would assist the enemy. The same scorched-earth policy would be applied in future campaigns against Greeks and Yugoslavs. During this campaign an Italian motorised column covered 300 kilometres across desert and mountain passes, reaching Gondar, the former capital of Ethiopia. The significance of this motorised march, an impressive performance by any standard, is that it demonstrated the feasibility of long-range motorised operations, anticipating the far more threatening and destructive behind-the-lines raids against the Axis rear carried out by the British Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) and Special Air Service (SAS) units before and after El Alamein. In turn, this raises the question why Italian motorised units – or German units for that matter – did not return the favour and attack the rear echelons of the British 8th Army. As Italian naval frogmen demonstrated in their successful attacks against HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Valiant at harbour in Alexandria, commando-style raids were no British monopoly.

It is tempting to dismiss the Italian conquest of Abyssinia as the inevitable outcome of a modern army being deployed against poorly equipped and primitive tribal formations. Yet, as Gooch notes, many took the view that it would be beyond Italy and would drag on for at least two years instead of the six months it actually took. British colonial disasters in the Zulu war (Isalwanda), the rampant forces of the Mahdi and the successes of the Boers show that victory for modern European armies against enemies considered to be inferior is far from a done deal, and when automatic superiority is assumed, and proper planning and preparation are ignored, things can go very badly wrong. Consider what happened to the Red Army when it invaded Finland in 1939 or the French in Indochina in the 1950s.

Italy’s intervention in the Spanish Civil War was propagandized as a crusade against the evils of Bolshevism – the evils were real enough – but was also prompted by the possibility that Spain could become a Soviet colony, an outcome that would have been a strategic disaster for the West. The murders of members of religious orders (6,238 deaths cited by Gooch) in the first months of the war, did much to drive support for the deployment of the Corpo Truppe di Volontarie (CTV), replete with the papal blessing. By the middle of February 1937 there were 48,230 Italian troops in Spain, supported by light tanks, artillery and mortars. Under command of General Ettore Bastico, Italian forces achieved a striking success in the battle of Santander. Thorough planning and flexibility were the keys and the CTV took 20,000 prisoners, having lost 424 dead and 1,556 wounded. In all, Italy deployed a total of 42,715 soldiers and 32,216 Blackshirt militia in Spain, incurring 3,318 dead and 11,763 wounded. Even if the campaign revealed shortcomings, Italian involvement was successful and raised the status of Mussolini’s regime and military.

General Ettore Bastico, Commons Wikipedia

By the start of WWII Italian forces had engaged in three major campaigns. Libya had been recaptured, Abyssinia subjugated and Franco’s triumph and the defeat of the Soviet intervention was in no small part owed to Italian forces. Unlike the Red Army, Italy’s generals engaged in serious arguments on military matters, as is clear from the many disagreements about the merits of divisions based on two regiments (divisione binaria) or three (divisione ternaria). Italian success in these campaigns demonstrated competence across an operational spectrum from counter insurgency, conventional operations involving ground forces supported by naval and air units and logistic efficiency. These undeniable successes meant that by 1st September 1939 Italian forces were battle-tested and experienced, forces to be reckoned with: Il Duce could look the Führer and the overbearing tedeschi in the eye, at least for the time being.

So what went wrong? To begin with, the raw numbers cited by Gooch show that Italian industrial production could not meet the demand for equipment – shipping, tanks, guns and planes – which were necessary for Mussolini’s expanding military ambitions. Carlo Favagrossa, the head of the General Commissariat for War production, concluded that even by 1945 Italy would not be fully ready for war, though he was able to report that ‘If there were no shortages of raw materials, the armed forces would be ready to fight for a year by the end of 1943. The sums of money he needed simply did not exist’.[3] Keeping up with the Germans was another problem. Having overrun its neighbours and plundered their resources, and blessed with Albert Speer’s organisational and administrative talents, a highly skilled workforce, and a vastly superior research and development base, Germany was a major industrial power: Italy was not in the same league and trying to keep pace with Germany placed intolerable strains on every aspect of Italian life. Resources were spread too thinly rather than being concentrated in pursuit of well-defined and achievable goals. As the war progressed Italy also learned another bitter lesson: the price for German assistance was German control.

Bundesarchiv Bild 183-C13771 Berlin, Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler

Comparing the conduct of Italy’s pre-WWII campaigns with what follows reveals a marked drop in the quality of planning and preparation. Italian strategic analysis was especially weak; more Micawber than the cool, pitiless appraisal of Machiavelli. With the French defeated by the Germans, Mussolini, acting like a hyena at the lion’s feast, sent his troops into the French Alps. In this four-day campaign the Italians lost 642 killed, 2,631 wounded and 616 missing. Gooch maintains that this brief campaign highlighted deficiencies in the Italian war machine, especially divisions configured according to the binaria system of two regiments per division. Possibly so, but the critical post-operational insight is that in addition to soldiers killed and missing, 2,151 Italians succumbed to frostbite. How was it possible that an army accustomed to operating in high mountains and equipped to do so, with dedicated Alpine units, could have incurred over 2,000 frostbite casualties?

Much worse was to follow when Italy invaded Greece on 28th October 1940. Lessons had not been learned. For example, Gooch notes that Italian troops were ‘under-equipped for winter warfare in the mountains’; that they had ‘no winter clothing’.[4] In some units soldiers had to dig in with bayonets because they lacked proper entrenching tools. Italian radio and communications links were not up to the task, shortcomings exacerbated by bureaucratic turf wars. Launched in the hope of a quick and easy victory, the Italian invasion of Greece was a disaster, just like the Red Army’s invasion of Finland the previous winter which was also planned and initiated on the assumption that it would be a walkover. The Finns did not fall into line, nor did the Greeks who ignored the Italian screenplay, showing tenacity and skill. Italian losses were 13,755 killed in action, 25,067 listed as missing and 50,974 wounded. There were also 52,108 listed as sick and once again high numbers of frostbite victims (12,368)[5], inexplicably so in view of Italian familiarity with mountain warfare.

Meanwhile, in North Africa the Italian Army was being very roughly handled by British and Commonwealth Forces (BCF). During the battle of Sidi-el-Barani (9th-11th December 1940) Italian forces were heavily defeated (38,000 Italians were taken prisoner). Further heavy defeats followed at Bardia on 3rd January 1941 in the course of which the Italian 10th Army lost 45,000 men, along with 430 guns, 190 tanks and hundreds of trucks. Disaster struck yet again when on 21st January 1941 Italian forces at Tobruk lost 24,000 killed, wounded and captured. With the loss of Benghazi to Australian forces on 7th February 1942, circa 20,000 Italians were captured along with 100 tanks, 200 guns and 1,500 vehicles. Another disaster was the battle of Keren (February – April 1941) which resulted in the loss of Massawa.

The naval war was not going well either. Carrier-based Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers of the Royal Navy attacked ships of the Italian fleet at harbour in Taranto on 11th November 1940, inflicting great damage, physical and psychological. On 28th March 1941, in the battle of Cape Matapan, the Italians lost three cruisers, Fiume, Zara and Pola and 2 destroyers, Vittorio Alfieri and Carducci. 2,200 men perished as well, including Vice-Admiral Cattaneo. British expertise in code breaking played a decisive role at sea as on land. Acting on ULTRA decrypts, a force of Royal Navy ships sallied out of Malta during the night of 8th/9th November 1941 and ambushed an Italian convoy carrying 389 vehicles, 34,473 tons of munitions, 17,821 tons of fuel and 223 Italian and German soldiers and civilians. The whole lot ended up in Davy Jones’s locker. A month later, two Italian cruisers, Alberico da Barbiano and Alberto da Giussano, were also ambushed and sunk by the Royal Navy on the basis of ULTRA decrypts.

The Mediterranean was also the theatre in which HMS Upholder set remarkable standards in submarine warfare. In September 1941, HMS Upholder formed part of a team of three submarines deployed against an Italian convoy of troop-carriers en route from Italy to Tripoli. Identifying the Italian convoy in moonlight, and without time to calculate an accurate line of attack, the captain, lieutenant-commander David Wanklyn, using his submarine as a shotgun, ordered torpedoes to be fired ahead of the position of the two troop-carriers, which from his position appeared to be overlapping, so creating a bigger target and enhancing the chances of a hit. The torpedoes were fired at a position ahead of the ships such that they would intersect the ships’ course: the range was 3 miles (!). In this first attack one of the troopships was sunk, one was damaged, another escaped. Sliding forward with the low rising sun behind her, HMS Upholder closed in to finish off the surviving but badly wounded liner, narrowly avoiding a collision with an Italian destroyer in the process. Having returned to base, Wanklyn learned that he had sunk two 19,000 ton liners, Neptuniaand Oceania. Earlier that year in May 1941, HMS Upholder had also dispatched the 18,000 ton troopship, Conte Rosso, with the loss of 1,300 Axis soldiers. For this action Wanklyn was awarded the Victoria Cross. More honours were to follow when in early 1942 Wanklyn was awarded an immediate bar to his DSO for sinking the Amiraglio St Bon, a newly commissioned and modern submarine and much larger than HMS Upholder. Gooch’s coverage of the naval war is generally good – the Regia Marina certainly had its moments – but he provides no details of the truly remarkable achievements of HMS Upholder, her crew and captain.

Photo12ssUnited2CH, HMS Upholder

As events were moving towards the decisive Battle of El Alamein, Italian forces were preparing to deploy into the vastness of southern Ukraine. The Italian Comando Supremo was overly confident about the campaign in Russia. Bearing in mind the less than impressive performances against Greece and the severe defeats inflicted by the British on Italian units in North Africa, there were no grounds for optimism. Leaving aside the likely performance of the Red Army, the greater distances and communications, much harsher and more diverse terrain, and brutal winters, would all thwart Italian dreams of martial glory. Some idea of the distances involved are evident in the fact that the Torino division, one of the divisions comprising the Corpo di spedizione italiano in Russia, had to march 1,300 kilometres (806 miles) merely to reach the zone of operations, only to discover that the shells of their 47 mm anti-tank guns could not penetrate the armour of the Soviet T-34. If Italian soldiers suffered from frostbite in operations against the French in the Alps and against the Greeks, and Italian logisticians barely managed to maintain any efficient level of resupply in a theatre of operations on Italy’s doorstep, how were they going to cope in Russia?

The Italian military attaché in Moscow, Colonel Valfré di Bonzo, informed his masters not to underestimate the Red Army. Apart from that sensible point, the rest of his assessment of the Red Army was of little use. For example, di Bonzo could have no way of knowing whether his claim that the Red air force had ‘made intelligent use of its experience in the Finnish war’ was reliable.[6] Stalin and his commanders were not going publicly to admit to any failings, and displays of air power on 1st May 1941 – the annual carefully stage-managed propaganda showpiece – provided no clues as to how the Red air force would perform in combat conditions. As it turned out, the Red Air force was overwhelmed by the Luftwaffe. Nor did di Bonzo (or Gooch for that matter) show any understanding of the damage inflicted on the Red Army by the Stalin purges, and his claims that Soviet commanders were coping with the German Blitzkrieg better than had been expected, as the Red Army was retreating in disarray, are not to be taken seriously.

In Anglophone history books the winter battles in southern Russia are defined by the fate of German 6th Army at Stalingrad, yet the soldiers of the Italian 8th Army who survived the horrors of the Eastern front on the right bank of the river Don, tell stories that crack the bones and freeze-dry the soul, stories of terrible cold, hunger, the exhausting retreat and time in Soviet captivity. The full range of human experience is there: courage, astonishing endurance, cowardice, incompetence, treachery and utter despair. At the start of the final battle on the Don, Italian strength was 229,888 men. In the ensuing battles and rout, losses amounted to 114,520. Of these 84,830 were listed as dead or missing and 26,690 listed as wounded, including almost certainly a large number of cold weather casualties (frostbite, gangrene and hypothermia). In all, this amounts to total losses of 111,520 (a shortfall of 3,000 is unaccounted for by Gooch[7]). Captivity was another nightmare. Approximately 70,000 Italians were captured by the Red Army. 22,000 perished on the long death marches to the camps, another 38,000 dying in the camps. In 1946, 10,032 were released and returned home. How many died of despair, of their wounds and of loneliness, abandoned by a society that, to use the hideous expression, had “moved on”? Gooch points out that some of the survivors recorded their ordeals and so ‘shaped much of the public memory of the campaign for the next half century’.[8] Eugenio Corti, who served in the Pasubio division, chronicled the disaster in his famous novel, Il Cavallo rosso (The Red Horse, 1983), surprisingly ignored by Gooch. A chapter or at the very least some synthesis of the Italian war experience on the Eastern front, as recorded in novels and memoir literature, would have added an effective and new dimension to Gooch’s study.

In Yugoslavia, the Italian occupation forces were confronted with long-standing and irreconcilable ethnic (racial) hatreds. To quote Gooch:

The Muslim-dominated population of Kosovo, which was handed over to Albania, itched to get their revenge on the Serbs who had persecuted them for decades. Terrified Serbs fled into Montenegro. So did Serbs from the Croatian borderlands escaping from the Ustaša. Currents of ethnic, nationalist and religious tension washed in all directions as Catholic Croats, Orthodox Serbs and Muslims began the bloody process of settling long-standing historic accounts.[9]

And this is why multiculturalism and diversity must fail, despite prolonged periods in which various ethnic groups in a finite space have given the appearance of getting on with one another. As soon as the opportunity arises for one group to seize an advantage over another group and to settle ancient scores, regardless how long both groups have been living together in apparent peace and harmony, this is what will happen. The Axis invasion merely provided the catalyst: and after Tito died in 1980 it happened again. The insane cruelty and horrors that confronted NATO and UN interventions in the 1990s were merely the latest examples of racial-ethnic hatreds and would have been no surprise to the Italian occupation forces in Yugoslavia.

On the island of Pago, Croats were killing some 50 Serbs and Jews a day, dumping the corpses in the sea. The Italian Marche division reported that ‘Ustaša officers offered starving mothers in prison a meal composed of their own children, roasted on a spit’.[10] In another village ‘the children of Orthodox Serbs who had managed to escape were killed, their hearts and livers removed and draped on the door handles of abandoned houses’.[11] To begin with the Italians adopted a policy of non-interference, merely watching ‘as the Ustaša committed rapes and bestial murders with impunity’.[12]

During the Italian occupation, General Vittorio Ambrosio initiated a policy of ‘“equidistance” between Serbs and Croats’ in the hope that this policy would win over both groups to collaborate with Italy.[13] It failed completely. Some fifty years later one of the approaches adopted by UN peacekeepers in the Balkans was to adopt or to try to adopt an even-handed approach in the belief that this would somehow convince all ethnic groups that they would be treated fairly. This approach fails because if the occupying power takes no action against the perpetrators of atrocities its inaction will be interpreted as indifference or worse, condoning such behaviour. If it does take action in the name of the nebulous fiction known as “the international community”, it will be seen as taking sides incurring the enmity of the group against which it acts. The pretence of even-handedness fails for another reason: wiping out the village of another ethnic group will not be seen as an atrocity by the perpetrators but will be seen as justified revenge for some distant or recent atrocity carried out by the targeted group of which the Italian occupation forces in the 1940s or UN forces in the 1990s could have no real understanding. If the Italian occupation forces under one unified command, unencumbered by intrusive media surveillance with its 24-hour news cycle and the Internet, and taking no account of the laws and customs of war could not solve the ethnic problem, then fifty years later, the malevolent, sentimental do-goodery of the divided, divisive, diverse, defective, destructive and deluded (D6) UN had no chance.

The unyielding hatred for the Italians and the partisan attacks mounted against them meant that the only kind of policy that would work was one of terror: executions, concentration camps, scorched earth, and razing villages. Measures taken by the Italians against those suspected of being partisans were very similar to those taken by the German army against Soviet prisoners suspected of being party functionaries or commissars, and may well have been influenced by the so-called Commissar Order. Unarmed males in a combat zone were deemed hostile and shot on the spot. Ruthless measures were also enacted against Italian soldiers who manifested defeatism or who lacked the will to fight. Gooch records that 28 Alpini, liberated from partisan captivity, were shot by their own side for having surrendered to their captors without a fight.

The Italian counter-insurgency ended with the surrender to the Western Allies. In Slovenia, Italy had lost 1,200 dead and 2,259 wounded and missing. 2,000 Slovenes perished in Italian concentration camps, another 1,620 had been shot. The moral chaos and disarray of the Italian occupation forces and just how hopelessly divided they were is indicated by the fact that the remnants of two Italian divisions, the Taurinese and Italia, along with the entire Venezia division, defected to the partisans after the armistice. It is estimated, notes Gooch, that some 7,000 Italian soldiers fought and died with the Yugoslav partisans after 8th September 1943 against their former ally, now the hated tedeschi.[14] Incidentally, the defection of these Italian formations superbly illustrates what Palmerston meant when he said that Britain (and, naturally, all other states) had no eternal enemies or friends, just eternal interests: spoken like a true Machiavellian.

The Italian occupation of Greece, like the bungled invasion, likewise, was less than glorious and soon descended into the all too familiar cycle of resistance and reprisals. The Axis occupation of Greece, as in Yugoslavia, also unleashed inter-ethnic hatreds. Bulgaria laid claim to Salonika and in the ensuing repressions some 15,000 Greeks died and between 70,000 and 200,000 were deported, others fled to the German and Italian occupation zones. Meanwhile, in northern Epirus, in pursuit of a Greater Albania, a Muslim militia set about ethnically cleansing the area of Greeks and Jews.

The stand-out statistic of the occupation is the number of Greeks who died of starvation, the first deaths occurring in Athens and Piraeus (both under German control). Sources cited by Gooch estimate that as many as 250,000 people may have died from the direct and indirect causes of famine in Greece between 1941 and 1943. Shipments of medicine and food delivered by the International Red Cross, encouraged by Mussolini, saved some lives. Greeks were also being crushed by debt, to the amount of 20,000,000,000 drachmae dumped on them by German and Italian moneymen to cover the costs of building fortifications in expectation of a British attack. With memories of such harsh exploitation, it is not surprising that the behaviour of the German-controlled European Central Bank during the 2010-2012 eurozone crisis evoked memories of war-time occupation, so many Greeks seeing it as yet another example of German-orchestrated rapacity.

Like any other self-respecting people under enemy occupation the Greeks formed partisan bands and the partisans (andartes), estimated by the Italians to number about 20,000, started to attack the occupiers. Reprisals ensued. Villages and homes were destroyed (14,888 between October 1942 and August 1943) and in the course of punitive operations the Italians killed 1,526 civilians. In various villages in the Trikkala region all the men were killed, and on the island of Mytilene civilians were machine-gunned to death, the bodies placed in sacks and cast into the sea. On 3rd February 1943, as the remnants of German 6th Army ceased fighting in Stalingrad, General Carlo Geloso, Italian military governor imposed a policy of collective responsibility on the population for partisan attacks, something which had long been German policy. The consequences of this decree were soon felt. On 16th February 1943, after Italian forces had been ambushed close to the village of Domeniko, 20 Greek hostages were shot on the spot, another 135 soon after, and the village was destroyed.

If the Greek andartes directly threatened the Italian occupation a more insidious threat was corruption among senior Italian officers who were enjoying a life of sporting pastimes and whoring instead of devoting all their energies to crushing partisans. To quote Gooch: ‘Stories of the Italians’ sexual laxness abounded’.[15] One unidentified general demanded ‘a ceaseless supply of young women’.[16] In conditions of famine food is currency and some Italian officers were deemed to have plundered rations intended for their men and passed them on to Greek women. Allowing Greek women and others to mix with senior officers in this way was also an unforgivable breach of security. Some of these women were almost certainly Allied agents or spying on behalf of the partisans, so explaining how the Allies became aware of this licentious behaviour. In Allied propaganda broadcasts the Italian occupation forces were satirized as the corpo erotico di occupazione which, on the assumption that senior German officers were not succumbing to the same level of vice, would have the desirable effect of arousing still greater contempt among the Germans for their Italian allies. In fact, the mutual resentment among Germans and Italians turned to hatred after the armistice. Gooch notes that about 10,000 Italians joined the partisans and fought against the Germans. The Germans responded with their trademark ruthlessness. Over the period of 21st-26th September 1943, approximately 5,000 Italians of the Acqui division were machine-gunned by the Germans on the island of Kefalonia. Gooch makes no mention of this massacre which merits a detailed analysis in his book. How did Mussolini react to the massacre of his fellow Italians by his German master?

Marshal Giovanni Messe, captured when Tunisia fell, maintained that Italy’s failures stemmed from the fact that none of Italy’s general staff officers knew anything about war. Early successes in Libya, Abyssinia and participation in the Spanish civil war offer no support for that view but these successes fed Mussolini’s ambitions and dreams which the industrial capacity of the Italian state was unable to satisfy. Campaigns undertaken before the start of WWII in the absence of British belligerence proved to be manageable, though Italy was pressing up against her limits. After September 1939, these shortcomings, hitherto glossed over, were brutally exposed.

As the war progressed, shortages of coal and power caused arms production to drop. ‘Allied carpet-bombing’, Gooch points out, ‘proved the final straw’.[17] Not only did Allied bombing destroy plant and disrupt and reduce production, it prompted Italian workers and technicians to abandon their places of work in search of safe havens. Calls for volunteers to man anti-aircraft defences – the aim was to recruit 40,000 volunteers – produced 3,000. Allied bombers were also punishing the Italian navy. The cruiser Attendolo was sunk at harbour in Naples and Italy’s last two heavy cruisers, Trieste and Gorizia, were destroyed by US bombers. US bombers also attacked the battleships Vittorio Veneto and Roma.

On assets alone, the Regia Marina was formidable yet proved unable to defeat the Royal Navy, a failure which had severe consequences for both Italian and German forces in North Africa. Counter-insurgencies in Greece and Yugoslavia drained energy and will. The statistics of death and destruction endured by the Italian 8th Army in the Russian lands tell their own story. Against the British Gooch accounts for Italian weakness as follows:

In the field, Italian generals lacked modern weaponry and transport. What they also lacked – and what some of their British opponents in the western desert had and would use against them – was experience of combined-arms warfare against a skilled and well-led modern army. Italy had no equivalent of the ‘100 Days’ which ended the First World War and her generals were at a severe disadvantage as a consequence.[18]

This is not a convincing explanation of Italian failure since whatever lessons or experience British generals may have gained in the last 100 days of WWI played no positive part in the deployment of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in 1940. In any case, such experience, as had been gained twenty years previously, was rendered redundant by the technological and doctrinal revolution in war which had been pioneered by the Germans from 1918. The effectiveness was brutally demonstrated against the Anglo-French forces in May-June of 1940. British and French deployment of armour was often in small groups, designed to support tactical infantry goals whereas German armour operated in large independent formations with the aim of achieving major operational breakthroughs. The principle was summed up by Heinz Guderian, the pioneer of combined-arms warfare (Blitzkrieg): Klotzen, nicht Kleckern (concentration not dissipation). In the interwar years some British generals were aware of these doctrinal changes and their implications but were ignored. It took the humiliating retreat to Dunkirk and the improvised evacuation to demonstrate what large, skilful and aggressively-led armoured formations could achieve. By contrast, there is evidence, some of it cited by Gooch, that one or two Italian generals, having arrived independently at the same conclusions as the Germans or having been influenced by German military thinking, were also conceptualising war in terms of speed and rapid deployment. General Alberto Pariani, for example, was pioneering his doctrine of la guerra di rapido corso. Pariani was a German speaker, had visited Germany and observed German exercises. The chances are that he had read and been influenced by Guderian’s essay, Achtung Panzer! first published in 1937. General Federico Baistrocchi was another advocate of high-tempo war. The Italians were also the first to demonstrate the possibilities of inserting troops by parachute when in 1927 they dropped half a dozen men with equipment, and Italian naval commandos enjoyed a well-earned reputation for skill and daring.

Senior Italian officers were noticeable absentees at Nürnberg. Gooch suggests that Italian commanders who violated the laws of war in Yugoslavia escaped punishment because of the exigencies of the Cold War and because Italy became part of the anti-Soviet camp, but then one has to account for the fact that were no major trials of Italian commanders who had presided over hostage shootings and scorched earth policies in Greece. In a speech to the House of Commons on 21st September 1943, Churchill hinted at why no action was taken. He had harsh words for Germany, sympathy for Italy’s plight and offered a way out for some of Germany’s other allies, noting that ‘Satellite states, suborned or overawed, may perhaps, if they can help to shorten the war, be allowed to work their passage home’.[19] This has some relevance for Italy’s defection from the Axis. Even if it were the case that Italy was ‘suborned or overawed’ by Hitler that it is hardly an excuse of any kind and one has to ask whether tacit assurances were given to the Italians that if they abandoned the Axis, Italian commanders would not be put before the International Military Tribunal. Is this what Churchill meant by being ‘allowed to work their passage home’?

Italian forces were, in any case, demonstrably guilty of war crimes and violations of the laws and customs of war before 1939. They committed these crimes not because they had been ‘suborned or overawed’ by Hitler but because they had succumbed to lust for cruelty. They used concentration camps in Libya in which large numbers of civilians perished. These violations continued in the Abyssinian campaign. When Ras Desta, the Emperor’s son-in-law, surrendered to Marshal Graziani he was shot. After Addis Ababa was occupied by Italian forces, thousands of men women and children were massacred and tortured in a three-day orgy of killing by gangs of Blackshirts. In his autobiography, The Life of My Choice (1987), Wilfred Thesiger, who formed a very close relationship with Emperor Haile Selassie and took part in Orde Wingate’s campaign in Abyssinia (1940-1941), cites a figure of 10,000 massacred by the Italians. Thesiger’s figure may well be too low. In his The Addis Ababa Massacre: Italy’s National Shame (2017), Ian Campbell puts the number massacred at 19,500, which in 1937 would have been about a fifth of the population of Addis Ababa. Priests, possibly as many as four hundred, were shot by the Italians in the monastery of Debre Libanos on 20th May 1937. Members of Ethiopia’s small intelligentsia that attended Western universities were also targeted. What emerges here, then, is an attack on the foundations of Ethiopian culture and a planned attempt to decapitate it, actions which are now considered to constitute genocide.

These Italian-perpetrated massacres anticipate the much greater slaughter of Chinese civilians by the Imperial Japanese Army in the winter of 1937-1938, now known as the Nanjing datusha and bear some resemblance to the mass shootings of Polish prisoners of war by the NKVD in 1940 which was also intended to decapitate an occupied country. The massacre in Addis Ababa did not reach the levels of the Nanjing datusha but was certainly far worse than some of the massacres carried out by German forces at, for example, Le Paradis (27th May 1940, c.96 victims, British prisoners of war), Lidice (9th-10th June 1942, c.224 victims) and Oradour-sur-Glane (10th June 1944, c. 600 victims) for which selected perpetrators were executed after the war. For example, in October 1948, SS Hauptsturmführer Fritz Knöchlein, who had ordered the Le Paradis massacre, was executed (hanged) in Hamburg, whereas Marshal Rodolfo Graziani ‘worked his passage home’ and escaped all punishment for his war crimes.

Memorial to Rodolfo Graziani

Any reader unaware of Italy’s war crimes would never learn about them in Mussolini’s War: Gooch completely ignores them. Ian Campbell’s The Addis Ababa Massacre is included in the bibliography – its absence would have attracted too much attention – but there is no mention by Gooch of the massacre itself, a crucial and inexcusable omission given the scale of this atrocity. In his summary of Graziani’s career, Gooch merely notes that ‘As viceroy of Ethiopia he hanged and shot “rebel” leaders, becoming markedly more ruthless after an attempt on his life on 19 February 1937’.[20] Well, Mussolini’s best friend took ruthlessness to new heights after 20th July 1944. Campbell had earlier examined the shootings of the priests in The Massacre of Debre Libanos: Ethiopia 1937: The Story of One of Fascism’s Most Shocking Atrocities(2014). This war crime and Graziani’s responsibility for it are also passed over in silence by Gooch. Consistent with Gooch’s silence is the fact that Debre Libanos, about 50 miles north west of Addis Ababa, is not indicated on the map of Ethiopia in Mussolini’s War: Gooch has psychologically razed it to the ground so removing the monastery and its victims from the historical record. There are other omissions.

Gooch finds no place for the work of the historian Emilio Gentile, one of Italy’s leading scholars on Italian Fascism and the pioneering scholarship of Ernst Nolte, above all Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche: Action Française, Italienischer Faschismus, Nationalsozialismus (1963), is ignored. The index is one of the worst I have encountered. Gooch lists 9 battleships of the Regia Marina but fails to list a single ship of the Royal Navy or even the wording ‘Royal Navy’. So whose fleet was responsible for interdicting and sinking Italian convoys and ships in the Mediterranean? Key words, such as ‘Negus’ and ‘Debre Libanos’, are absent and Wilhelm Keitel’s rank is given as General: he was promoted to Generalfeldmarschall in July 1940.

Omitting any mention of these crimes might please a certain number of Italians who would prefer not to be reminded of Italy’s war crimes but it does not make for sound and objective scholarship. Gooch’s tendency to play down or to ignore the statistics of Italian atrocities but at the same time to highlight detailed (and valuable) statistics of Italian losses is, in fact, evident throughout Mussolini’s War. Gooch informs the reader that 6,238 members of religious orders were murdered in Spain; he provides an estimate of the number of Greeks that died of starvation during the Axis occupation, circa 250,000, and estimates the numbers of Italian soldiers that ended up fighting against the Germans in Yugoslavia and Greece after the armistice as, respectively, 7,000 and 10,000. In contrast to this precision he provides no figure or anything reliably close – and offers no explanation why he is unable to provide any – for the number of civilians who died in Italian concentration camps in Libya. Some sources put the number of deaths in these camps as high as 45,000 out of 80,000 incarcerated.

The contributions of Mussolini and other Italians to the post-war vision of Europe are another aspect to Mussolini’s war which are treated superficially by Gooch. In the period after his rescue by Otto Skorzeny, Mussolini delivered a speech in which he set out his vision of the New Order in Europe. In the context of WWII, this speech meant nothing, but it would be wrong to dismiss it out of hand, as Gooch does, since Mussolini’s thoughts on the New European Order were part of a much bigger planning and intellectual effort setting out the future of a United States of Europe in the event of a German victory. Mussolini had dealt with this theme in 1934 in an interview with the French paper, Intransigeant, in which he advocated pan-European unity and the inculcation of a pan-European spirit. Unlike the Germans, Mussolini also realised that the Axis failure to provide a cogent challenge to the provisions of the Atlantic Charter (14th August 1941) had enabled the Western Allies to set and to dominate the post-war agenda for Europe. Substantial contributions to the idea of a United States of Europe and its infrastructure were also made by Giuseppe Bottai, the education minister, Giuseppe Solaro, Camillo Pellizzi, Raffaele Ciasca, Carlo Emilio Ferri and Alberto De Stefani. Their contributions indisputably helped to shape the policies of the European Economic Community and European Union. There is, in other words, a direct and clear line from the aspirations and ideas of Fascist Italy and National-Socialist Germany for a post-war Axis-dominated Europe and what actually emerged after 1945 and what in 2020 is embodied (embalmed) in the EU.

The main strength of Mussolini’s War lies in the numbers and data of Italian production, casualties and losses assembled by Gooch which, in turn, make the absence of data on war crimes all the more conspicuous. With these numbers one can get a grasp on where things went wrong for Italy and why. Gooch cites numerous documents generated by Italian industrial and military circles. These reports have to be summarised but it is not enough for Italian generals and bureaucrats indirectly to address the reader in this way. Their claims and insights need to be challenged, the omissions highlighted, and this means that the historian, Gooch in this case, must take control of the material and impose and concentrate his analytical presence and force so that key points can be extracted, and that lies and evasions can be exposed. The historian must not hide in the shadows: the reader wants the historian’s judgement, if only to disagree with it.

Claudius, Vatican Museum

Dr Frank Ellis is a military historian

ENDNOTES

[1] Gooch, p.10

[2] Gooch, p.27

[3] Gooch, p.75

[4] Gooch, p.149

[5] Gooch, p.185

[6] Gooch, p.217

[7] Gooch, p.296

[8] Gooch, p.296

[9] Gooch, pp.232-233

[10] Gooch, p.235

[11] Gooch, p.235

[12] Gooch, p.235

[13] Gooch, p.240

[14] Gooch, p.267

[15] Gooch, p.274

[16] Gooch, p.274

[17] Gooch, p.351

[18] Gooch, p.419

[19] Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, volume V, Closing the Ring, Cassell & Co. Ltd. London, 1952, p.142

[20] Gooch, p.xviii

© Frank Ellis 2020

Hubris to Nemesis, as with the Senior Partner. A European Tragedy in two parts.

The courage of many Italian servicemen themselves needs better recognition.

A. James Gregor is still a good source of information on fascist ideology, policies and achievements.