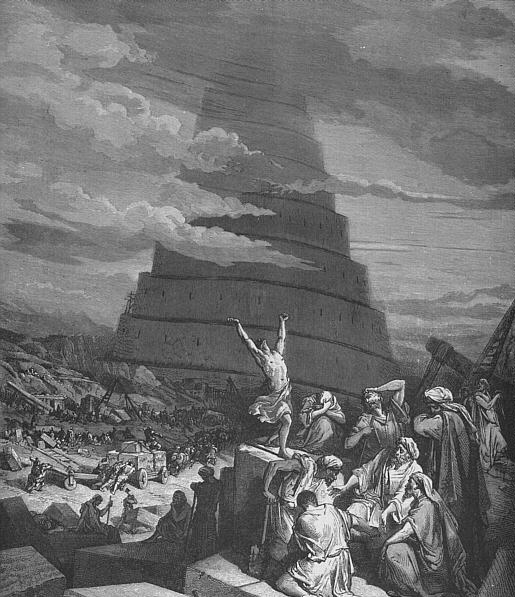

Gustave Doré, Confusion of Tongues, credit Wikipedia

Can of Worms

Dr A Kneen on extremism

Who wants to be labelled an ‘extremist’? There can be adverse social, professional, and financial consequences for those so labelled. A person deemed an ‘extremist’ could even be referred to the government’s Prevent Programme[1]. Although generally considered something to be avoided, it is often unclear exactly what is meant by the term. However, the government has released a new definition of the term ‘extremism’[2] Extremism, we are told, is the promotion or advancement of an ideology[footnote 3] based on violence, hatred or intolerance[footnote 4], that aims to negate or destroy the fundamental rights and freedoms[footnote 5] of others (1); or (2) undermine, overturn or replace the UK’s system of liberal parliamentary democracy[footnote 6] and democratic rights[footnote 7]; or intentionally create a permissive environment for others to achieve the results in (1) or (2).

The types of behaviour listed below are indicative of the kind of promotion or advancement which may be relevant to the definition and are an important guide to its application. The context below goes on to list 3 behaviours that could constitute ‘extremism’. The first listed aim of extremism covers: ‘Behaviour against a group, or members of it, that seeks to negate or destroy their rights to live equally under the law and free of fear, threat, violence, and discrimination.’ The second aim includes ‘undermining…liberal democracy’ and the third aim is ‘enabling the spread of extremism’. Further context is then provided, including the statement that:

The lawful exercise of a person’s rights (including freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of expression, freedom of association, or the right to engage in lawful debate, protest or campaign for a change in the law) is not extremism. Simply holding a belief, regardless of its substance, is rightly protected under law. However, the advancement of extremist ideologies and the social harms they create are of concern, and government must seek to limit their reach, whilst protecting the space for free expression and debate.

Of course, many of the terms used in this definition are themselves problematic and could be the subject of much debate.

Using the terms and phrases in their normal sense, ‘The threat from extremism’, as the government avers, has been steadily growing for many years.’ Indeed. it was almost exactly 4 years ago (23rd March 2020) that the government ordered a ‘lock down’ of the country. Fundamental rights and freedoms of others were ‘negated and destroyed’. Freedom of association was severely curtailed as people were told to stay at home. If they had to leave home, they were told to stay 6 feet apart from others. Even in their own homes, the police could break in, and did, if they suspected people were associating with each other in an ‘unpermitted’ manner (unless it was the government holding parties). Protestors and those campaigning for a change in the law were attacked and arrested by the police. Matters that could be considered as ‘democratic rights’ were removed as people were subjected to various tyrannical policies, including mandates for an insufficiently tested, and now known to be potentially harmful, ‘vaccine’.[3] Extreme intolerance was shown towards those who did not comply with ‘lockdown’ rules. There was intense censorship of those who challenged aspects of the rationale on which the ‘lockdown’ was based.

There are two main ways in which the term ‘liberal’ is currently used. In the classical sense of the term, it is maintained that freedom and individual rights are important, and government is to be limited. In the progressive sense, there is an emphasis on civil liberties, ‘minority rights’ and social justice – often with the associated promotion of various issues (such a LGBTQ, etc.). The actions of the government in the past 4 years do not qualify as ‘liberal’ under either of these perspectives, quite the contrary. In fact, the government exercised immense power over people in a tyrannical abuse of civil liberties and freedoms.

The first aim of extremists, listed in the new definition, is to negate or destroy fundamental rights and freedoms. It entails behaviour against a group, or members of it, that seeks to negate or destroy their rights to live equally under the law and free of fear, threat, violence, and discrimination. Since most religions hold various tenets that consider certain behaviours as inherently unequal to others: inequality and/or discrimination would be inherent. In this sense, some religions are arguably ‘extreme’ and incompatible with ‘liberalism’. However, this then presents a contradiction in relation to the civil liberties of such religious people to themselves live equally and without discrimination.

The second aim listed states that ‘extremist’ behaviour includes attempts to ‘undermine […] the UK’s system of liberal parliamentary democracy and democratic rights’. As noted above, if attempts to undermine a person’s democratic rights is extremism, then this definition could qualify the government as extremist – due to the manner in which such a definition could infringe upon various matters that are usually considered as ‘democratic rights’, including free speech, religious freedom, and the like. It is also unclear exactly how far the interpretation of ‘undermining’ could go. Would all dissent be considered ‘extremist’? Would the pointing out of flaws in our ‘liberal parliamentary democracy’ be considered as ‘extremism’? Would exposés of various matters as we have seen in the past (e.g. the 2009 Parliamentary ‘expenses scandal’[4], the 1994 Parliamentary ‘cash for questions scandal’, various sex scandals, etc.) be held to undermine parliamentary democracy and thereby constitute ‘extremism’?

Also included within the second aim of ‘extremism’ is: Establishing parallel governance structures which, whether or not they have formal legal underpinning, seek to supersede the lawful powers of existing institutions of state. There are already established religious bodies in this country that pass judgments on various matters, including civil disputes, etc. There are also many other groups that potentially could fall under this definition such as those associated with home-schooling groups. Are these to all now be considered as ‘extremist’? Or, again, is this to be selectively applied in a discriminatory manner (providing further internal inconsistency)?

The new definition of ‘extremism’ notes ‘the pervasiveness of extremist ideologies in the aftermath’ of the October the 7th incident. Since this date, thousands of Palestinians have been killed in what South Africa, at the Hague International Court of Justice[5], referred to as genocide. The government have made various statements condemning protestors during this period – protestors exercising what are their ‘democratic rights in a ‘liberal democracy’. The government also supports the actions taken by Israel against Hamas – and, if the reports of what is actually happening in Gaza are true, the rights of the Palestinians are not being protected.

There are allegations that protestors against Israel are making some people feel uncomfortable and/or scared. However, this would not provide valid justification for removal of the freedoms and civil liberties of protestors. The current criminal law provides adequate protection for anyone subjected to threats, violence, etc. The current idea of banning anything that someone does not like is not applied evenly. There is the phenomenon of ‘cry-bullying’ that must always be considered in such matters, whereby someone claims victimhood as a means to bully/control others. This phenomenon is frequently encountered in daily life when people ring the police purporting to be victims, as a means to exert control over others.

Of course, the promotion of fear to further social and political objectives was pursued during the past 4 years by the media and the government – and the definition of terrorism is the causation of fear amongst people to further such social and political aims. For example, a document from SAGE (The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies) explicitly discusses use of the media to, amongst other things, increase the sense of personal threat[6]: to wit, ‘Use media to increase sense of personal threat’. Members of SPI-B are reported as regretting this tactic. Scientists on a committee that encouraged the use of fear to control people’s behaviour during the Covid pandemic have admitted that its work was “unethical” and “totalitarian”.[7]

If ‘undermining’ the government is now viewed as ‘extremism’, how can what is normally understood as ‘liberal democracy’ continue to function? Are we still allowed to criticise the government without being referred to the Prevent Programme as potential terrorists? Would it be considered as ‘undermining’ to ask if the government itself does not fall under the new definition of being an extremist, if not a terrorist, organisation?

Dr Alice Kneen was awarded a Bye-Fellowship at Magdalene College, Cambridge. She is the author of Multiculturalism – What Does it Mean?

ENDNOTES

[1] E.g. see: Prevent | Counter Terrorism Policing

No Smoke Without Fire Part 5: PREVENTing a War on Domestic Terror in the United Kingdom? | UKColumn

The Prevent Programme is mentioned on the government definition page qv

[2] See: New definition of extremism (2024) – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[3] All this extremist suppression was presented as being justified by the threat of a flu – a flu with a mortality rate stated by Dr Anthony Fauci to be comparable to that of a bad seasonal flu and that was allegedly caused by a supposed virus that has still to be isolated.

[4] Exclusive: the real story of the MPs’ expenses scandal (telegraph.co.uk)

[6]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/882722/25-options-for-increasing-adherence-to-social-distancing-measures-22032020.pdf

[7] Telegraph 14th May 2021:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/05/14/scientists-admit-totalitarian-use-fear-control-behaviour-covid/

This is an important article and I congratulate the Editor on its publication.

“Extremism” is a confected abstract noun related to the adjective “extreme” – similar to “round”, “endless”, “balanced”, “central” or “relative”, devoid of proper content, but given the spurious quasi-ideological suffix “-ism”.

Its definition, application and enforcement depends on its political serviceability to the controlling authority at any given moment or in any circumstance. As Humpty Dumpty explained to Alice, words can be used to mean anything: it depends on who is master.

We need more not less freedom of speech, with the specific exception of incitement in any media of any crime or violence against any individual or group, whatever their opinion or identity. There is a particular difficulty arising from the nature of the Muslim religion with its concept of Dar al-Harb that requires special discussion, a subtle way of dealing with the issue, too long to elaborate here.

It is an irony that sacred texts of the s0-called Abrahamic faiths themselves can be quoted as exhibiting religious/”racial” hostility, the Talmud against Christians, the New Testament against Jews and unbelievers, and the Quran against Jews, Christians and unbelievers.

Alice in Blunderland, watch your tongue, or you’ll be getting a GOOD-Bye disfellowship. See the list from Academics for Academic Freedom.

The Scottish hate speech legislation is a retrograde threat.

Scotland, Wales, London and England are under foreigner rule, but if Dishy Rishi wants to go out with a British Bang instead of a Woke Whimper, he should try to scrap the Equality Act and its “protected” groups which he attacked in his leadership contest as a source of many miseries.

Unfortunately, this country is in decline. We have a totalitarian government who brought in lockdown,shut down debate, and labelled anyone who questioned the science a conspiracy theorist.

It opens a can of worms for the government if the population has freedom of speech. Extremism, control, and fear mongering seems to be government policy.

Alice, a great article and a Stirling effort.

Worms turn – in unexpected soil.

See e.g. John Gray, “These Times”, The New Statesman, 12 April 2024, p.22.

Essays like these in “leftwing” publications deserve wide circulation.

Pingback: A Conspiracy to Silence and Control - The Quarterly ReviewThe Quarterly Review