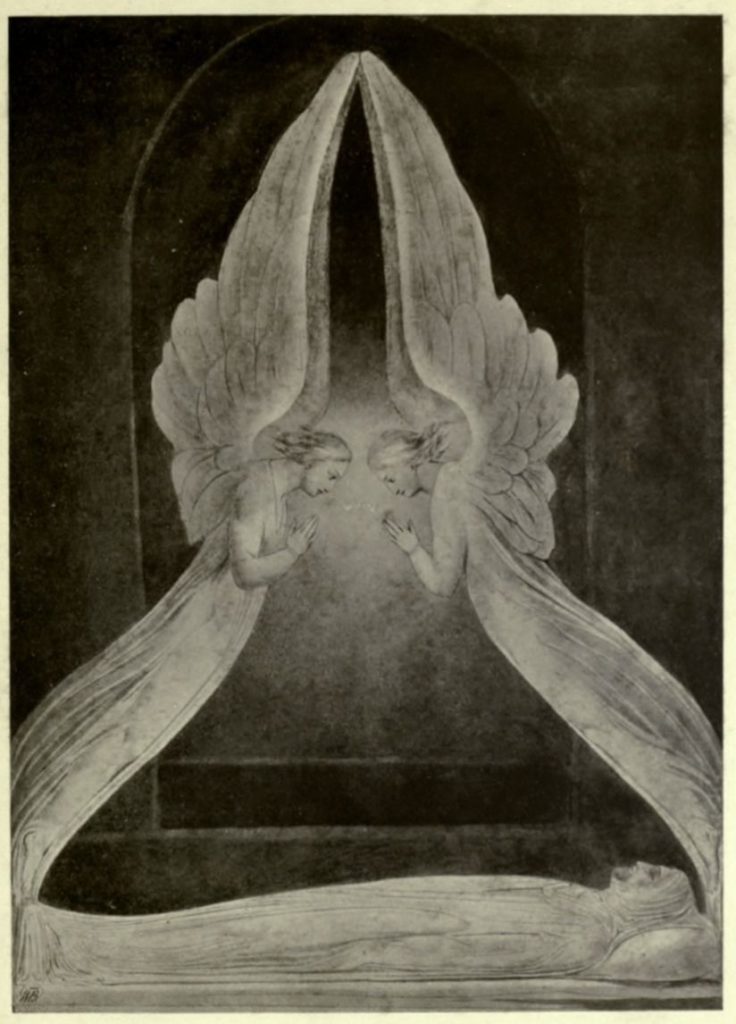

William Blake, The Angels Hovering over the Body of Christ in the Sepulchre c.1805. Credit Pinterest.com

Blake, Envisioned

William Blake, an exhibition, Tate Britain, 11th Sept 2019 to 2nd Feb 2020

William Blake, by Martin Myrone & Amy Concannon, Tate, 2019, reviewed by Leslie Jones

William Blake was born in London, on 28th November 1757, at 28 Broad Street, where his father James ran a hosiery shop and haberdashery. Blake’s family were dissenters and as Simon Schama points out, he was buried in a dissenters’ cemetery (Radio 4, 9th September). Although the approach taken by Martin Myrone and Amy Concannon, curators of this exhibition and authors of the accompanying book, “is determinedly historicist and materialist” (page 14), they overlook the influence of Dissent over Blake’s thought. Not so Alan Moore, who in an afterword, refers to “…Blake’s Moravian parentage…[and] the dissenting Christian faiths that he grew up with…”

For Nonconformity informs Blake’s vision of the world, which is essentially eschatological*. The German mystic Jakob Böhme (1575–1624) endorsed the Lutheran view that “humanity had fallen from divine grace into a state of sin and suffering”. He emphasised the role of the fallen angels who had rebelled against God. Fifth Monarchists, likewise, were ever mindful of Daniel’s prophecy that four successive kingdoms will eventually be replaced by God’s kingdom. They constantly referred to the Number of the Beast. All of these themes are explored by Blake. Angels, fallen or otherwise, throng throughout his oeuvre.

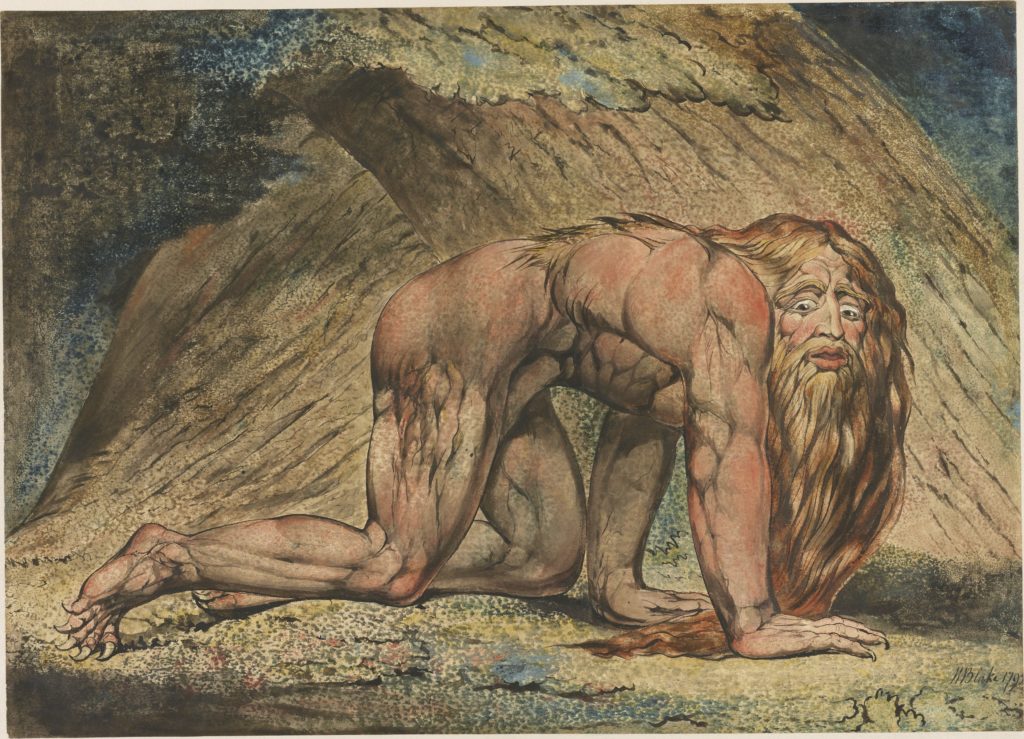

Willam Blake, Nebuchadnezzar, 1795-c. 1805

The authors of the accompanying book/catalogue note that Blake’s engraving work for the publisher Joseph Johnson, in the 1770’s and 1780’s, brought him into contact with radicals like Mary Wollstonecraft. He illustrated and engraved her Original Stories from Real Life (1791). But given his background in Dissent, Blake’s political radicalism, as expressed by his support for the American Revolution in America a Prophecy, and by his opposition to the slave trade, as in The Song of Los (1795), was hardly adventitious.

William Blake, Ancient of Days, 1827

The mythological character Urizen, invented by Blake, “is the embodiment of reaction and oppressive law”, and is possibly a depiction of George III, “overwhelmed by the loss of the American colonies” (page 63). The youthful character Orc, in contrast, is “the emblematic embodiment of the rebellious Americans”. Just as well, then, that Blake’s Prophetic Books of the 1790’s were not commercially viable and only printed in small numbers, given “the paranoid political atmosphere” of the time (page 82).

While apprenticed for seven years to the engraver James Basire, Blake sketched Gothic tombs at Westminster Abbey and was enthralled. Like the poet Robert Southey and the social critics William Morris and Thomas Carlyle, the England of the Medieval era, for Blake, was unsullied by commerce and industrialisation. He loved plainsong and considered the Middle Ages an organic, spiritual epoch. His Illuminated Books, combining text with illustration, defied the trend towards mass production.

In the late 1760’s, walking across Peckham Rye, Blake saw “…a tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars”. As the distinguished psychologist Hans Eysenck maintained, creativity is linked with trait psychoticism.

*Cf. Blake, Peter Ackroyd, Vintage, London, 1999, chapter one

There is (or was) a mural on a building at the edge of Peckham Rye, depicting Blake’s tree, full of angels. The traffic, buses and indifferent people all go by…

Blake’s words, set in Parry’s Jerusalem, give us a vision of a better time to come – the very earth trembling beneath those chariots of fire. Yet how monumentally sad and dispiriting it was to see, at the Last Night of the Proms on Saturday, Remainiac EU flags being waved in accompaniment to the noble grandeur of this national hymn. Incongruous, an insult and just wrong in every way.

The Last Night of the Proms was politically corrected throughout, from beginning to the welcome end. The Fat Lady sings over the LGBTI+++ Rainbow and the Woke rubbish. The whole thing has become an unintentional farce.