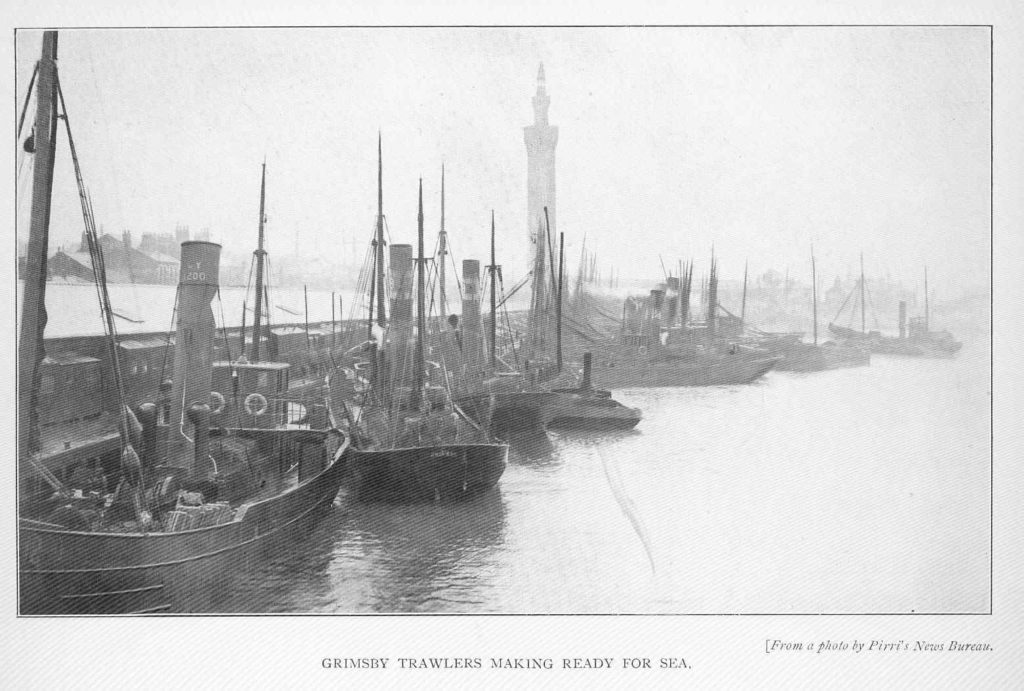

Grimsby trawlers making ready for sea

Battered and Bruised

Bill Hartley, on beholding Grimsby

The House of Fraser store in Grimsby is set to close. For anyone who thinks that a department store represents retailing at its best, the place is a depressing sight. Large areas of floor space stand empty; elsewhere the remaining racks of clothes offer 20% off the existing sale price. Forlorn staff, soon to lose their jobs, show minimal interest in the few shoppers who pick over the remnants.

House of Fraser is situated in a bright and cheerful mall, a once positive attempt to modernise shopping in the town. Grimsby is an old seaport with very little in the townscape which is attractive, apart from the Minster church of St. Mary and St. James. Not far away is the Humber, a brown and muddy river which drains much of Yorkshire. There used to be a ferry across but no-one wrote a song about it.

Visiting Grimsby brings a sense of being at the end of the line. The town lies fifty miles up the road to no-where, in flat countryside next to that unlovely river and is a byword for social problems. Those with long memories may recall when this was the largest fishing port in the world, an industry brought down by the Cod War and the Common Fisheries Policy.

This happened so long ago that outsiders view it as being of only historical interest but locals retain their grievances and they get passed down the generations. When a dominant industry is pulled out of a town, something more than employment disappears.

Grimsby has what must be one of the largest Poundland stores in the country and its doing brisk business.The port is still busy, shipping in Volkswagens from Germany and there is plenty of food processing work nearby. If house prices are a good barometer of prosperity, then Grimsby isn’t doing too badly and yet the town is described as one of the worst places in England to grow up poor. Some of the population, it seems, has moved on but others are stuck, perpetuating social problems. This is one of the most depressing things about Grimsby; wandering the streets a visitor sees a new generation emerging, to be trapped in the same dead end as its elders. There is a paradox here. On the outskirts things look good with decent housing and a pleasant aspect over to the southern horizon, where the Lincolnshire Wolds rise up from the flat farmland. The town centre, though, seems stuck in the era of old Grimsby and like the fishing industry is withering away.

The Royal Society of Public Health measured various British towns, ranking the quality of their high streets by what sort of businesses they have. Using this measure, Grimsby presents a bleak picture: bookmakers, tanning studios and a range of fast food outlets. Even the pubs are on a race to the bottom. Most of them display their prices and advertise which beers are available at below £2 a pint. Each has its relay of smokers who huddle in the doorways, listlessly watching the passers-by.

An unfortunate legacy of Grimsby’s past is the dearth of interesting buildings dating from its days as a fishing port. This may be due to the fact that fish is a perishable commodity and there was no need for storage. The trawlers unloaded and fish was moved to market as fast as possible. Wherever the merchant classes established themselves, it wasn’t in the town centre. Essentially, it is a town with little architectural merit, once described by the Daily Telegraph as a place which cares nothing for its heritage. Speaking of which Grimsby does possess that symbol of a town which has seen better days: a ‘heritage centre’. Last year its windows were boarded up after an attack by vandals.

It’s difficult to imagine what could be done. In contrast, Liverpool had its Albert Dock, which pump primed other waterfront developments. In Grimsby, the shopping mall represents the only improvement in the townscape. The town hall, incidentally, lies on the outskirts. Imagine the Victorian city fathers of say Bolton or Barnsley sticking the main civic building out on the edge of town. Even the precincts of the Minister are without the grand town houses that used to go up around large places of worship, in the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries.

There is one significant building in the town. Opposite the railway station stands the Yarborough Arms. This huge hotel was built when the railway first arrived and it survived the inevitable attempt at demolition in the sixties. The Yarborough is now owned by Wetherspoon’s who maintain it, both as a hotel and a place where you can get cheap food and drink. It is the only large place in town where you can eat in well maintained surroundings. The customers are uniformly working class and the steps outside provide a meeting place for kids and young mothers with pushchairs.

The people at the town hall recognise that Grimsby has a social problem group, to wit, the white working class population. In its usual unimaginative fashion, officialdom approaches the problem by chucking grant money at the locals. They begin by identifying these people as a ‘community’. Then comes the aforementioned heritage centre, followed by a newsletter to tell the locals about themselves. Such initiatives soon die off because they are an easy target for budget cuts. With ideas exhausted next come the excuses. One mentioned recently by the council leader is the isolation of the town, overlooking the fact that it doesn’t seem to have been too difficult to shift fish out of the place.

If the town centre reflects the decline of Grimsby then it should be realised that retailing is unlikely to return in strength. In the North, some towns have begun to accept this and meet the challenge. Above street level are buildings that used to be lived in and could be again. It is an alternative to getting people back into town centres as shoppers and has the potential to generate a sense of ownership and pride.

Linked to this there needs to be an understanding that the damage was done years ago. A relict population was left behind of families who were defined by their jobs at sea. Many must have realised that they would never work again and after them came another generation who absorbed the grievances of their fathers. It is possible that they are beyond reaching. If so, then it is the young who need to be targeted. Something has to be done to give them self respect and aspiration. Grimsby’s townscape and its young people both need attention and the two might be linked to give the latter a better sense of place. Otherwise, there will be yet another generation of heavy drinkers, waiting for the pubs to open.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Like this:

Like Loading...

Battered and Bruised

Grimsby trawlers making ready for sea

Battered and Bruised

Bill Hartley, on beholding Grimsby

The House of Fraser store in Grimsby is set to close. For anyone who thinks that a department store represents retailing at its best, the place is a depressing sight. Large areas of floor space stand empty; elsewhere the remaining racks of clothes offer 20% off the existing sale price. Forlorn staff, soon to lose their jobs, show minimal interest in the few shoppers who pick over the remnants.

House of Fraser is situated in a bright and cheerful mall, a once positive attempt to modernise shopping in the town. Grimsby is an old seaport with very little in the townscape which is attractive, apart from the Minster church of St. Mary and St. James. Not far away is the Humber, a brown and muddy river which drains much of Yorkshire. There used to be a ferry across but no-one wrote a song about it.

Visiting Grimsby brings a sense of being at the end of the line. The town lies fifty miles up the road to no-where, in flat countryside next to that unlovely river and is a byword for social problems. Those with long memories may recall when this was the largest fishing port in the world, an industry brought down by the Cod War and the Common Fisheries Policy.

This happened so long ago that outsiders view it as being of only historical interest but locals retain their grievances and they get passed down the generations. When a dominant industry is pulled out of a town, something more than employment disappears.

Grimsby has what must be one of the largest Poundland stores in the country and its doing brisk business.The port is still busy, shipping in Volkswagens from Germany and there is plenty of food processing work nearby. If house prices are a good barometer of prosperity, then Grimsby isn’t doing too badly and yet the town is described as one of the worst places in England to grow up poor. Some of the population, it seems, has moved on but others are stuck, perpetuating social problems. This is one of the most depressing things about Grimsby; wandering the streets a visitor sees a new generation emerging, to be trapped in the same dead end as its elders. There is a paradox here. On the outskirts things look good with decent housing and a pleasant aspect over to the southern horizon, where the Lincolnshire Wolds rise up from the flat farmland. The town centre, though, seems stuck in the era of old Grimsby and like the fishing industry is withering away.

The Royal Society of Public Health measured various British towns, ranking the quality of their high streets by what sort of businesses they have. Using this measure, Grimsby presents a bleak picture: bookmakers, tanning studios and a range of fast food outlets. Even the pubs are on a race to the bottom. Most of them display their prices and advertise which beers are available at below £2 a pint. Each has its relay of smokers who huddle in the doorways, listlessly watching the passers-by.

An unfortunate legacy of Grimsby’s past is the dearth of interesting buildings dating from its days as a fishing port. This may be due to the fact that fish is a perishable commodity and there was no need for storage. The trawlers unloaded and fish was moved to market as fast as possible. Wherever the merchant classes established themselves, it wasn’t in the town centre. Essentially, it is a town with little architectural merit, once described by the Daily Telegraph as a place which cares nothing for its heritage. Speaking of which Grimsby does possess that symbol of a town which has seen better days: a ‘heritage centre’. Last year its windows were boarded up after an attack by vandals.

It’s difficult to imagine what could be done. In contrast, Liverpool had its Albert Dock, which pump primed other waterfront developments. In Grimsby, the shopping mall represents the only improvement in the townscape. The town hall, incidentally, lies on the outskirts. Imagine the Victorian city fathers of say Bolton or Barnsley sticking the main civic building out on the edge of town. Even the precincts of the Minister are without the grand town houses that used to go up around large places of worship, in the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries.

There is one significant building in the town. Opposite the railway station stands the Yarborough Arms. This huge hotel was built when the railway first arrived and it survived the inevitable attempt at demolition in the sixties. The Yarborough is now owned by Wetherspoon’s who maintain it, both as a hotel and a place where you can get cheap food and drink. It is the only large place in town where you can eat in well maintained surroundings. The customers are uniformly working class and the steps outside provide a meeting place for kids and young mothers with pushchairs.

The people at the town hall recognise that Grimsby has a social problem group, to wit, the white working class population. In its usual unimaginative fashion, officialdom approaches the problem by chucking grant money at the locals. They begin by identifying these people as a ‘community’. Then comes the aforementioned heritage centre, followed by a newsletter to tell the locals about themselves. Such initiatives soon die off because they are an easy target for budget cuts. With ideas exhausted next come the excuses. One mentioned recently by the council leader is the isolation of the town, overlooking the fact that it doesn’t seem to have been too difficult to shift fish out of the place.

If the town centre reflects the decline of Grimsby then it should be realised that retailing is unlikely to return in strength. In the North, some towns have begun to accept this and meet the challenge. Above street level are buildings that used to be lived in and could be again. It is an alternative to getting people back into town centres as shoppers and has the potential to generate a sense of ownership and pride.

Linked to this there needs to be an understanding that the damage was done years ago. A relict population was left behind of families who were defined by their jobs at sea. Many must have realised that they would never work again and after them came another generation who absorbed the grievances of their fathers. It is possible that they are beyond reaching. If so, then it is the young who need to be targeted. Something has to be done to give them self respect and aspiration. Grimsby’s townscape and its young people both need attention and the two might be linked to give the latter a better sense of place. Otherwise, there will be yet another generation of heavy drinkers, waiting for the pubs to open.

William Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Share this:

Like this: