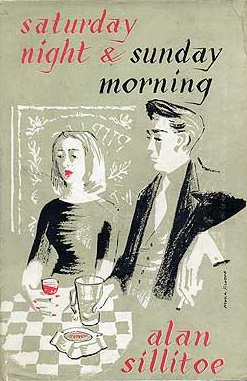

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, credit Wikipedia

Arthur Seaton Approaches Eighty

Bill Hartley contemplates the decline of a once fractious class

Arthur Seaton would be close to eighty by now, that is if he’d survived so long. The Angry Young Man of Alan Sillitoe’s 1958 novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning did have what we might describe these days as an unhealthy lifestyle. Food was generally fried whether cooked at home or brought in from the Fish and Chip shop; the only form of takeaway available in 1950s Nottingham. Salad did put in an appearance at one meal in the book but it was Christmas and so something exotic was to be expected.

Then there was the smoking that could be done anywhere during Arthur’s waking moments: home, factory or pub. As for booze, well Arthur’s consumption would nowadays fit into the binge drinking category we hear so much about. He did have an occasional night off but for Arthur drinking during the week was simply limbering up for the excesses of the weekend. When we first meet him he is about to collapse down a flight of stairs having consumed thirteen pints and seven gins.

Arthur did possess a bicycle but he was not a prototype of the lycra clad zealots one sees today. For him it was a way of getting to work or to the nearest canal bank for a spot of fishing; the latter being an activity he might have listed under ‘recreations’ although it’s likely the term would have had to be explained to him. Other spare time activities of the non public house kind were restricted to football and chasing after women.

It was the era of You’ve Never Had It So Good played out against the ever present clatter of the Raleigh cycle factory where Arthur could earn as much as fourteen pounds a week as a lathe operator. Back then there was something uncomplicated about material prosperity. Arthur visits an aunt who greets him sat next to an enormous coal fire. His cousin is a miner and the nationalised industry supplies each collier with concessionary coal. They need never again worry about an unheated house. For his part Arthur is satisfied at being able to afford a wardrobe full of clothes. The older generation aspire to a television set.

Arthur’s rebelliousness has a clarity and simplicity forged by recent memories of unemployment hunger and war. He is vaguely anti government on the basis that government gets us into wars and then requires the likes of him to fight them. More specifically he loathes the boss class that extends down to the foreman he sees on a daily basis. People like Arthur didn’t do Aldermaston marches. He knows government doesn’t listen and his is a daily battle with an authority that he believes is out to grind him down. Hence his work rate is subtly adjusted so the time and motion people don’t dock his wages. Arthur’s ironic motto is: ‘it’s a hard life if you don’t weaken’.

He reserves special contempt for those striving to ascend the greasy pole and join the boss class, particularly since Arthur is astute enough to notice that taking on even a modest level of responsibility at the cycle factory, adds an additional layer of stress to the physical effects he feels from grinding out hundreds of pieces each week: the back aches and occasional bouts of sickness he believes are caused by the lubricants he has to handle. Health and safety was in its infancy back then.

There are some social observations voiced by Arthur which were well ahead of their time. He notes with sneering contempt how his neighbours are happy to be sedated by television (this in the days when there were only two channels). ‘Dead from the neck up’ is a favourite expression of his and he uses it mercilessly. It is interesting to have someone in the 1950s fantasising about destroying every television set in his street.

Sillitoe revisited Arthur in his penultimate novel Birthday. Published in 2001 it is a bleak piece of work. Arthur has though survived into the new century, doing so on his own initiative. The Raleigh cycle factory was not so lucky (they make them 20% cheaper now in Vietnam). Arthur was astute enough to broaden his skills, learning how to operate every machine in the factory so he could take his know-how elsewhere. He would have been contemptuous of a life on benefits. Being told ‘you’re entitled to it’ is an expression Arthur would have interpreted as another form of submission to authority.

Despite Birthday giving the reader a tour of 21st century Nottingham this is no exercise in nostalgia. Seen through Arthur’s eyes the crime and decline of the city are simply elements of change. Most of the factories are gone and whilst he hardly seems to regret this he notes the decline of working class solidarity forged in adversity. Arthur sees little threat from the underclass that has emerged to replace it, bred by welfare dependency, believing even at his age he is capable of defending himself against such feeble individuals.

He may have been right. The book features a brief appearance by Arthur’s feckless son. It is a depressing picture of an unemployed and possibly unemployable individual who cannot even find the energy to dredge up resentment towards the situation in which he finds himself. Father has adapted and survived. Success for his son is scrounging £20 from Arthur, probably to spend on drugs.

Arthur Seaton is a survivor of the old working class still wanting to smash the television, seeing it as the portal of a movement to keep the masses quiet whilst maintaining them as consumers of things they don’t really need. Is Arthur still out there? Perhaps but television has made us more familiar with a new working class figure. The idler Jim Royle glued to an armchair whilst ranting impotently at his television in The Royle Family.

BILL HARTLEY is a freelance writer from Yorkshire.