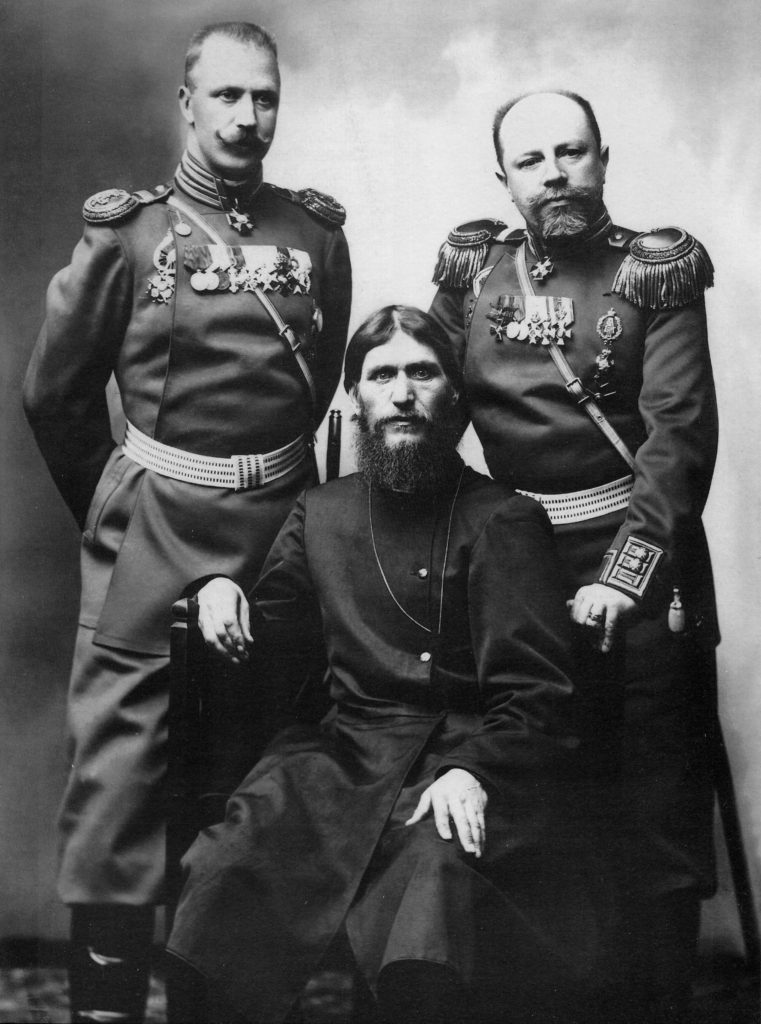

Left to right prince Mikhail Putyatin, Grigory Rasputin and Colonel D Loman

Alas, Poor Russia

Leslie Jones attends an outstanding exhibition

Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths, British Library, 28th April 2017 to 29th August, 2017

Propaganda is evidently the leitmotiv of this exhibition. The insidious influence of the faith healer Grigorii Rasputin over Tsar Nicholas II and the Tsarina, Alexandra (as depicted in the poster above) was a godsend to opponents of autocracy, especially during the Great War. In ‘A very close friend’ (New York Review of Books, December 2016, a review of Douglas Smith’s Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs) historian Orlando Figes shows that the monarchy lost control of the presentation of the news “at a time when its survival depended upon it”.

King George V reportedly liked his relative Nicholas (an honorary Admiral of the British Fleet, no less) well enough. But following the February Revolution of 1917 and the Tsar’s enforced abdication, King George declined to offer his first cousin asylum, having been advised by the British Ambassador in Russia, Sir George Buchanan, that it might cause an uprising here. The Tsarina, who was the daughter of the Grand Duke of Hesse, was allegedly pro-German. Indeed, it was widely believed that Alexandra and Rasputin were in league with the Germans. Moreover, Nicholas was considered by some as The Hanging Czar, to quote the title of a 1908 pamphlet by Tolstoy, which is displayed in W J Chamberlain’s English translation.

On 30 April 1918, following the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, the Imperial family was imprisoned in the aptly named ‘House of Special Purpose’, in Yekaterinburg. In due course, they were butchered in the basement. A church now stands on the site of the building.

Execution of the Romanov family Alexander Palace, 1917

Some members of the extended Russian royal family, however, were safely evacuated from the Crimea, as another telling and poignant exhibit testifies, to wit, a guest list from HMS Lord Nelson, compiled in April 1919.

The theme of competing, historical meta narratives informs the section of the exhibition that addresses the Civil War (1917-1923) between the Whites and the Reds, amongst other factions. White atrocities is the subject of the Bolshevik poster, seen above. Conversely, Who is Happy in Sovdepia? shows an exhausted worker atop a pile of useless banknotes. While in another propaganda poster, Redistribution for the Reds, the Bolsheviks are driven into hell by the White cavalry and the Archangel Michael. Contrary to the Soviet myth of the indestructible alliance between the peasantry and the working class, in yet another White poster (see below) we behold Bolshevik soldiers looting a Cossack village. Grain requisitioning by the Soviet state or Prodrazverstka caused peasant revolts in 1918 and widespread famines during 1920 and 1921.

“Russia’s sorrow is great”, bemoans 1915: Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Tsar Nicholas II, and her beloved son the Tsarovitch, who is playing with her pearls. The exhibition Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths bears witness.

1915: Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Tsar Nicholas II, and her son the Tsarovitch who is playing with her pearls. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

LESLIE JONES is Editor of QR

Readers may like to get a copy of the “New Statesman”, 5-11 May 2017, which instead of welcoming the Marxist revival, is surprisingly filled with devastating attacks on Soviet Communism and its western “useful idiots”. Part of the neo-con campaign against Corbyn perhaps, but an historic turnaround to treasure.